- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

Without understanding how your inner nature evolves, how can you possibly discover eternal happiness? Where is eternal happiness? It’s not in the sky or in the jungle; you won’t find it in the air or under the ground. Everlasting happiness is within you, within your psyche, your consciousness, your mind. That’s why it’s important that you investigate the nature of your own mind.

Share

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

26

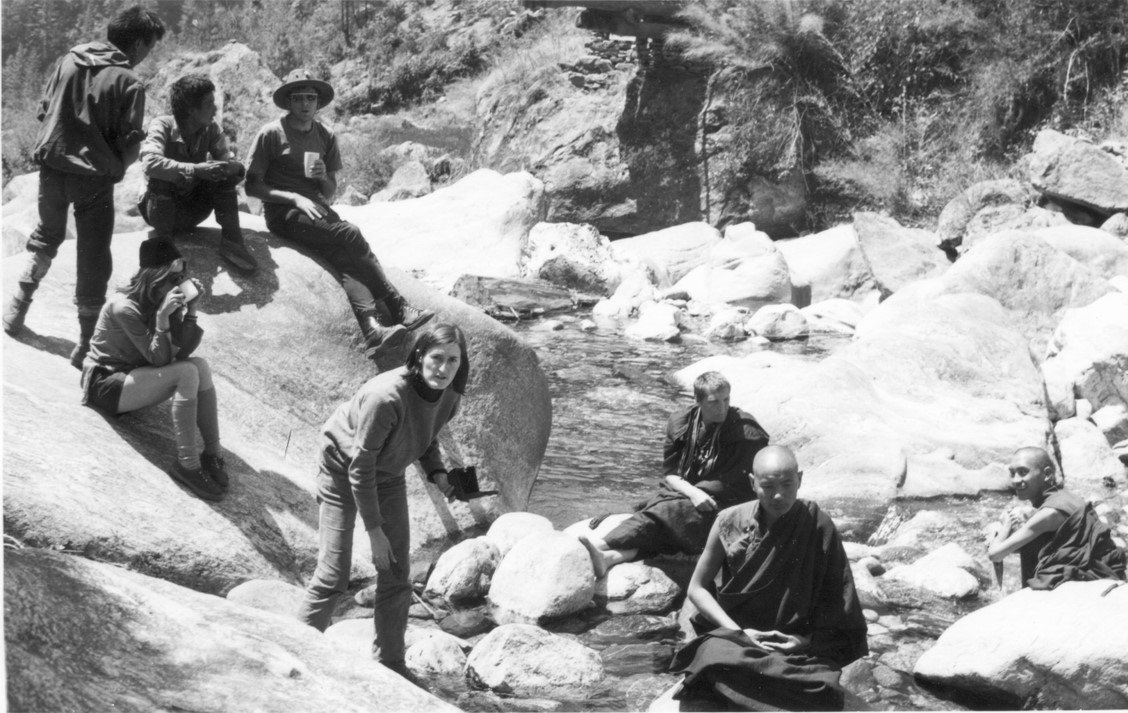

The trekking group to Lawudo, pictured from front: Lama Yeshe, Chip Weitzner, Dorje Sherpa, Judy Weitzner. Above: Zina, Max, and behind Max, Lama Zopa Rinpoche. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Below is Judy Weitzner’s extraordinary and historic account of a very early visit to Solu Khumbu, Nepal with Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche in 1969. This was the first time that Rinpoche had returned to Lawudo since he left for Tibet as a young boy and the group included Zina Rachevsky and Max Mathews.

This story was first published in three parts in the Love Lawudo monthly newsletters #11, #12 and #13. We’ve added many photos from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive collection for this posting. We hope you enjoy!

Introduction

In the Fall of 1968, Chip Weitzner and I took off on a round the world adventure. For months prior to leaving I brought home stacks of books from the Richmond Library, compiling a list of all the intriguing spots in various countries around the globe. I listed the sites on index cards for each country we might visit and compiled a manilla file. Some stops were clear. We knew we would stop in Hong Kong to see Chip’s sister, Janet who was a China scholar. We had promised a Peace Corps friend that we would visit him in Nepal. When it came time to purchase a round the world ticket for $1258.00, I discovered that we were allowed as many stopovers as we wanted, as long as we went forward and did not zig or zag excessively. Basically, I put every place on the ticket that we might want to visit, north of the equator. The ticket was well over an inch thick, and shocked every airline and travel agent who handled it. We stayed a week or two at each destination. Hawaii, Japan, Hong Kong, Macau, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Bali, India,…and, then, NEPAL!! “You must see the Himalayas before you die” was a quote that drove me.

Nepal in 1968 had not been open to tourists for very long. Most who came were mountaineers who stayed in the Yak and Yeti hotel. We stayed at the Panorama Hotel, a hang out for anthropologists in Kathmandu taking a break from their field studies and for various government aid workers.

Early on, a Peace Corps friend took us out for lunch at the Peace Restaurant, across from the American Embassy. It was reputedly a safe restaurant to eat in, and by our standards was very inexpensive. Hanging on the wall was a map of the flags of the world. I studied it from afar while eating my lunch. I spied a unique looking flag, a kind of double pennant that featured the sun and the moon on the two parts. I had always been attracted to the symbology of the sun and moon, so I announced to my friends that I saw a flag I liked and wanted to go to that country. I walked up to the map to find out that it was Nepal’s flag. I said, “Well, I guess I am where I want to be, then.”

We stayed in Nepal from November 1968 until June 1969. We secured teaching jobs at the American International School, which was a means of support as well as a long visa. I taught 3rd grade and Chip taught PE. Max Mathews was the beautiful and creative 4th grade teacher as well as the proprietor of Max’s Gallery. We soon became friends, spending much of our weekend time together. She would send her driver and car – a red, mile-long 1932 Hudson – to pick us up after we settled in a small house out in the countryside. Her “penthouse apartment” on the upper two floors and roof of a downtown building was a salon of sorts. She had lived and taught in many exotic places, and friends of hers would drop in on their travels through Kathmandu.

It was at Max’s that we met Zina, a friend of hers from Greece. Zina, who I heard was a Russian princess, a fashion model and a Hollywood starlet, was now a Tibetan Buddhist nun and dressed in maroon robes. Her entourage consisted of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa who were her Buddhist teachers. She had met them in Darjeeling at a monastery. Zina and the Lamas joined our coterie. We planned parties, dinners, picnics and adventures together in Max’s Hudson. Then another old friend dropped in on Max. It was Lorenz Prinz, a German photographer who had returned to Nepal to complete a book of photos of the Himalayas. It was Prinz who made the arrangements and guided our preparations for our famous life-changing trek in the Himalayas which I write about here.

Trek group to Lawudo, Lorenz Prinz, left, with Max Matthews, Judy Weitzner, and rest of the team. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Preparations for the trip to Solu Khumbu

Lorenz Prinz had returned to Nepal to complete work on a book of photographs of the Himalayas. He had driven overland from Germany with his assistant in a VW van loaded with darkroom equipment. He rented a small house near where we lived out in the country and set up a dark room. He invited me to come and watch him work a few times and I found the alchemy of photography fascinating. Prinz always wore a jaunty beret. He confided that he had had two brain surgeries to remove tumors. Both times it was predicted that he would never walk again and both times he retaught himself how to crawl and then to walk. He was determined to finish the work on his book. Fortunately, he had experience trekking in the Himalayas so we joined forces and he guided us in our preparations for our trip. Max and Chip and I were going on our Spring break from teaching at Lincoln School, so we couldn’t afford the time it would take to hike all the way up to the Everest Region. Prinz made arrangements for chartering the airplanes. Zina and the Lamas wanted to come too. Lama Zopa had not returned to his birthplace since he was taken to Tibet as a young child. He wanted to see his family and return to his village. Zina had invited her French filmmaker friends to meet them in the mountains and film Zopa’s return to his village.

One of my students at Lincoln School was the daughter of a Canadian consultant to the Royal Air Nepal airlines. The family would occasionally invite me to dinner. He was totally appalled at what he found in Nepal. He told me that even the pilots don’t wear seat belts, there were no functioning control towers, and the airplanes weren’t regularly serviced. He said he was amazed that there weren’t frequent crashes given how they operated. I was quite sobered by this conversation. I then mentioned that Prinz had hired the King’s airplane to fly us to Lukla. I was hoping he would say that the King’s plane was serviced regularly and I shouldn’t worry, but what he said was “That plane can’t fly to Lukla. The Lukla landing strip is too short for it – only 900 feet – your plane needs 1200 feet. You need to have a STOL plane (Short Take-off and Landing). A contract group called Arizona Helicopters has them.” I told him that Prinz had tried and that there were no planes available for the flight up, but they could only come and pick us up. I was worried, but I rationalized the situation by thinking that they wouldn’t send a plane to a place where it couldn’t land. They know better. They wouldn’t sacrifice the King’s airplane for some charter money.

In the days before we left, we all scrambled and scrounged for equipment and food. In those days you did it all yourself. There weren’t even accurate trekking maps, much less jackets, sleeping bags and boots to fit big Western feet. We had schlepped big boots and down jackets in anticipation of trekking. Zina was in charge of equipping the Lamas. Even though Max wanted to come along, she seemed to pay little attention to what it entailed. Max needed to find some sort of outdoor clothing. She was an elegant dresser and I had never seen her in pants or “practical” shoes. Fortunately, Prinz had plenty of experience and guided us through the preparations.

Flight to Lukla

The morning of the flight Max made her appearance in a long brocade chuba (Tibetan dress), a silk blouse and beautiful flowers pinned in her hair. I couldn’t believe that she intended to trek in that outfit. Yet Max was oblivious to my reservations about her outfit and lifted her skirt to show me that she had managed to purchase some Nepalese army boots. These were her gesture to mountain gear. Other than that, style always trumped functional clothing. Prinz and his assistant arrived with camera gear slung around their necks. Zina arrived with Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa. They wore their robes: no sturdy shoes, no jackets, no hats, nothing else. I was upset with Zina for not taking better care of them, but they seemed content with what they had. I always seemed to be playing the role of the practical pig with my very interesting, but totally impractical friends.

While we waited for the pilot to arrive, the Nepalese were loading the plane with all kinds of things, nothing belonging to us. They were filling the aisles up with packages. When I saw them loading a child’s tricycle, I knew that it wasn’t ours. Prinz finally stopped them from putting any more cargo in the plane arguing that we were paying for the plane and it should be reserved for our stuff. Thank God he stopped them when he did, because I am sure we would have crashed with any more weight.

Plane flying out of Lukla airport, 1974. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Finally, the pilot turned up. He was not the regular pilot. The regular pilot was sick, he explained. The replacement pilot had never flown this route before, but he was willing to give it a try. The problems with this flight were mounding up. Had I been a little more savvy, I would have proposed we cancel the whole idea, but we had all planned this for so long. I was thinking “Surely, they wouldn’t have someone who didn’t know the route fly us in a plane that couldn’t land where we were going, that was also overloaded with cargo, would they?” Well, the answer to that question was…”They would!”

We boarded, some of us scrambling over the cargo in the aisle. We chose seats, which had no seat belts, just as the Canadian had predicted. We tied ourselves down with rope and bungee cords. (Good old bungee cords…I never travel without them. They have saved my bacon more than once). We took off, circling to gain altitude and marveling at the view of Bodhanath and the hilltop that would become known as Kopan from the air. The Lamas were seated in the rear seats. When I looked back at them, they were smiling, but I noticed both of them clicking away on their malas, and thought they might be nervous on their first airplane ride. The reverie of the aerial views of villages, temples and magnificent landscape was abruptly replaced with sheer terror as we hit TURBULENCE. This was not the rocking and rolling that we had experienced in big airplanes. Our plane was buffeted around so hard, it felt like it would break apart! Sometimes we would be blown sideways. I swear our wing was only feet away from the mountainsides. Sometimes we would drop downwards, lifting my heart to my throat. I was pretty sure this would be my last flight. Prinz’s assistant fainted dead away ending up in the aisle. My worry about her took my attention away from our impending disaster for a short time and I was grateful for the distraction.

The pilot looked back at us occasionally after some near miss and rather than inspiring me with steely-eyed confidence he would shrug his shoulders and give us a “what me worry?” look, like what did you expect from someone who has not flown this route before? I looked back at the Lamas again, and prayed that they could keep us aloft with whatever power they had. Finally we started banking and circling around over a deep valley. I looked out and way, way down I saw there was a cleared field, a landing strip. It must be Lukla.

The problem was that we couldn’t approach the strip directly as the plane was too big. We had to spiral around and down with mountains close to our wing tips. We were all terrified, and then sick and nauseous as we descended in circles and finally set down on the runway, hitting and bouncing. The problem was that if the plane undershot the runway, we would have crashed into a mountain.

But, oh no, we had overshot the already too short runway, and we were racing toward the mountain at the other end. “Why didn’t I listen to the Canadian?” I was thinking. “He was right, we can never stop in time”. I braced myself for the crash into the mountain, when suddenly the pilot hung a U-turn throwing us all to the side of the plane. I was sure we would roll over, but, no, we were headed back down the runway, the way we had come. He brought the plane to a stop and we piled out as quickly as possible. Most of us just laid on the ground, hugging the earth, grateful to be alive.

The treking group stops by a river in Kusum on the way to Phagding. The party included Lama Yeshe, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Max Mathews, Zina Rachevsky, Jacqueline Fagan (a New Zealander who had been at Villa Altomont), Judy Weitzner and her husband, Chip Weitzner. Photo donated by Judy Weitzner to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Some Sherpas approached us wanting jobs as porters and Prinz hired some of them to carry our gear for the trek. They loaded our things into large baskets which they carried on their backs supported by a strap around their forehead. We regrouped at a tea house in Lukla and then began a really pleasant, fairly flat walk up a beautiful valley. I was lulled into thinking that trekking wasn’t so tough after all and that I had been over-worried about preparations.

We spent the night in a Sherpa home, a cousin of our guide, Ang Dorje. I had to crouch to get through the very low doorway. I was ushered inside and offered a seat along the wall. Slowly patterns of white dots began dancing before my eyes. At first I couldn’t figure out whether it was a visual hallucination, but as my eyes became used to the dark I could see that they were drawn on the black walls and shelves. Next I began to make out the glint of handmade metal pots arranged in order of size. As they came into view I marveled at their beauty and craftsmanship. In Kathmandu they sold ugly aluminum pots. These Sherpa pots were amazing. There was a hearth in the corner where the woman of the house presided over the fire and the cooking. The few shafts of light revealed a smoke filled room. I looked up above the fire for a chimney. There was none–just a small opening. All the rafters were thick with black soot which had a dark iridescence when it caught the light. It must have taken decades to build this thick layer. I thought to myself, “In Nepal, they haven’t invented the chimney, yet”.

Later, when Prinz arrived, he failed to duck low enough as he entered, and hit his head on the overhead beam. He was reeling at the blow. When I went to help, he explained the problem was that when he had had brain surgery for a tumor on his brain before coming to Nepal, the doctors had not replaced the section of skull that had been removed. His beret disguised the fact that there was only skin and no skull . He had taken a direct blow to the brain. I was worried about him, but he was stoic and determined to go on. Really, there was no other choice.

That evening, we sat around the fire with the family. I was already beginning to fall in love with the kind and generous Sherpas. Usually, there was someone sitting and spinning wool. Someone else might be weaving on a loom in the corner, or outside in the sunshine. In the US I had been a part of the counter culture which valued self-sufficiency and hand-crafted items. Many of my friends were “back to the land hippies”, experimenting with gardening, carpentry and alternative forms of society. We wanted to rely less on manufactured goods. We wanted to live in communities rather than the isolated nuclear family model of the previous generation. Sherpa society seemed to be living our ideal. I was smitten.

For dinner, our cook prepared some of the food we had brought along. Our Sherpa mother, (Ama) cooked a huge pot of small potatoes. I watched in fascination as the family pinched the cooked potatoes, removing the skin with one gesture and popped the whole peeled potato into their mouths. They shared some potatoes with us and I tried, in vain, to master their technique. I got nowhere and had to painstakingly peel my potatoes in little strips. To this day, I think of the Sherpas when I cook potatoes and wish I knew their magic peeling mudra.

I thought that this was the perfect time to offer my gift. I had heard about the problem of goiters in the mountains. I also knew that salt was a valuable commodity and Sherpas had been involved in the salt trade with Tibet. The American commissary stocked packages of miniature Leslie salt shakers–iodized, of course. I had purchased several to offer to our hosts along the way. Thinking the family would enjoy the salt on their potatoes. I showed them how to twist the lid and sprinkle the salt out. Once they saw that it was salt, they opened the top to the pouring spout, held the shaker above their open mouths, poured, and swallowed the contents in one gulp. Apparently, they really liked salt, but not exactly as a condiment.

The next morning I saw a beautiful woman with a huge goiter. “Why couldn’t USAID do something practical that would change peoples lives for a small investment in iodized salt,” I thought. Next I saw an elderly woman lying on the ground at the side of the path. She was too weak to sit up and was obviously quite ill. Nonetheless, she put her hands together in a namaste greeting and flashed a big smile. I summoned our guide to translate. I said that I was concerned about her and I thought she should go to the hospital. She protested that she couldn’t walk and she didn’t want to go. Besides, she needed to look after her grandchildren. Apparently, someone would carry her outside each morning so she could watch the kids. I told her family that I would hire someone to carry her to the hospital, but she said “no” to that, too. I reluctantly left her behind, but reflected on the fact that despite her extreme disability, she had a valued job to do and that it mattered more to her than the possibility of getting medical help. She was supremely calm and content with things as they were.

The next Himalayan moment came when it was time to cross the river on what the Sherpas would call a bridge. What I saw were some ropes suspended across the river with some boards cradled along the center. There were gaps between some of the boards. I walked a few steps out and discovered that my footsteps caused an undulating rhythm which combined with the swaying made calculating where I put my foot down very challenging. One misstep, and it was a long way down to the river. I rejected offers of help because I knew I didn’t want anyone else on the “bridge” with me. When someone else was walking on the boards, they set up their own unpredictable undulation, making it even more difficult to gauge and direct my next step. The Sherpas noticed my trepidation and told me that when Sir Edmund Hillary built bridges, they stayed in place, but when Sherpas built bridges (here they made a swooping gesture) they washed down the river. Their light-hearted humor only made things worse for me. Holding the waist high rope as I went, I made it across. I failed to inquire whether I had crossed a Sherpa bridge or a Hillary bridge,

We meandered along the river on an easy trail for quite awhile. We were strung quite far apart down the trail. That day, I began to realize that one of the secrets to trekking was to walk at my own pace – not trying to keep up or slow down to walk with someone else. Establishing a rhythm of breathing and walking and paying attention made all the difference.

Max and I were together, moving at the same speed. Suddenly the trail seemed to come to a dead end right at the base of a mountain. There was a pathway heading upward quite steeply, but I couldn’t imagine that it was our trail. I assured Max that we did not have to climb, while I looked around for the proper route, but couldn’t find it. We decided to wait until the Sherpas came along to show us the way. When they came, they pointed upward at the very steep trail. Yes, that was the trail and we were going to have to walk up it. I had completely convinced myself and Max that the upward trail couldn’t possibly be the right one. We had no choice but to start climbing. Not only was it “up”, it was 2,000 feet up, taking us to over 11,000 feet. Without trekking guides or maps, we had no idea we were ascending so quickly, without acclimatizing. Later on much more was known about altitude sickness.

Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa helped us along. Whenever we needed a boost, Lama seemed to make an appearance to help. Several times when he offered a hand, I wondered, “How did he get in front of us? I thought for sure he was behind.”

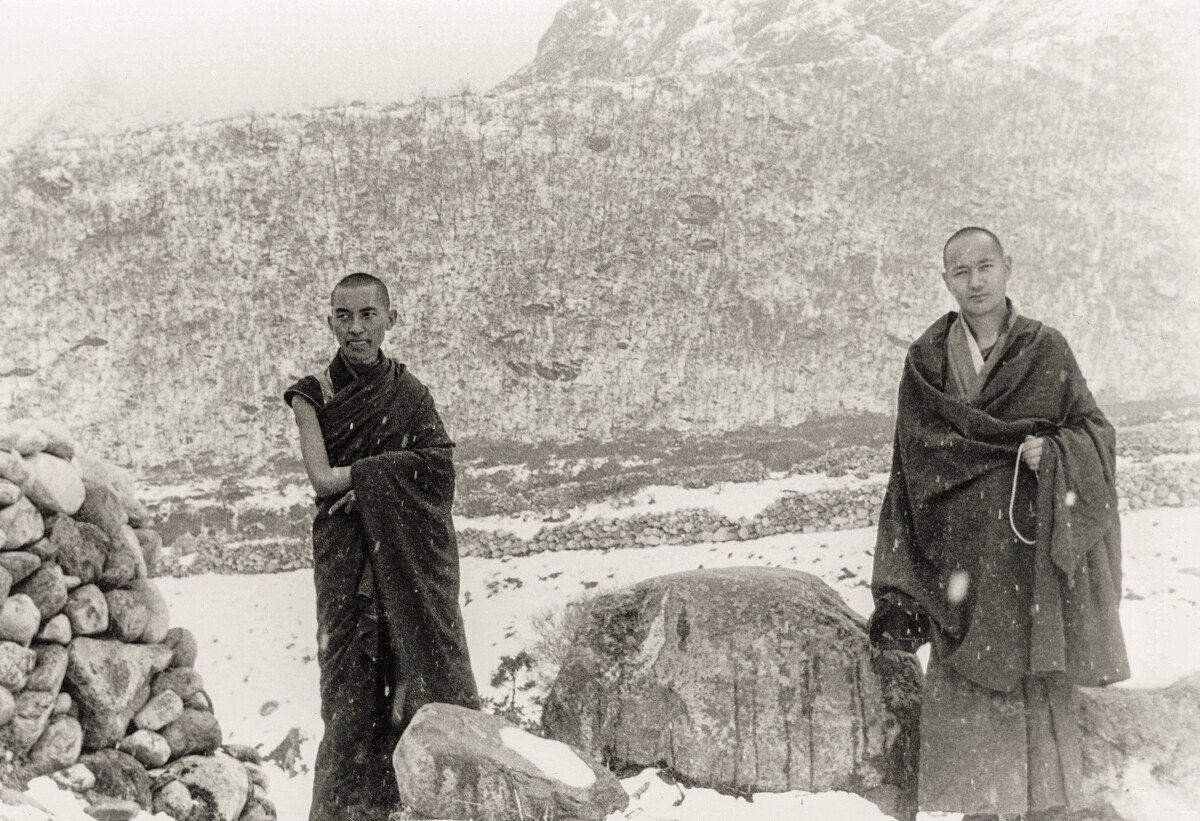

Lama Zopa Rinpoche (left) and Lama Yeshe at Thangme, during the first trek to Lawudo in 1969. Photo by Georges Luneau.

I was nearing utter exhaustion when I came upon a Sherpa serving the Lamas hot tea at the side of the trail. He had hiked down from Lama Zopa’s village to greet him. We all sat around and had tea on the side of the mountain. Slowly, I was getting the picture that Lama Zopa was an important person and that the Sherpas were very happy that he was coming to visit. I heard them relay the message up the trail. “Lama’s coming. Lama’s coming” They took the trouble to walk for a day to give the Lamas tea. . I had thought that we were bringing the Lamas along on our trek, but I was beginning to realize that we were beneficiaries of being in their company. Another thing was becoming clear to me, the Sherpas had their own method of tracking people in the mountains. When you met someone on the trail they would ask “where are you going” and “where are you coming from.” Lama Zopa’s arrival had already been telegraphed to his village by this word of mouth method.

When we reached Namche Bazaar, Max and I just sat down on the trail overlooking the famous market town of the Himalayas. I was envying the big birds who were effortlessly gliding on the updrafts. I wanted to trade places with them and soar rather than trudge along. I was tired and crabby. I needed to muster the energy to walk to the guesthouse where we would spend the night. It had turned cold and I was bundled up in my down jacket, but still freezing. Lama Yeshe came along and sat down next to us, admiring the view. Lama held my cold hands in his, trying to warm them up. Suddenly, I was jarred out of my self-pity and noticed what was going on. Here I was, dressed in layers and down and still cold. Lama had his sleeveless shirt and light robes, yet he was warm as toast and trying to take care of me. I asked him, “Lama, how can you do this? How is it that you are warm and I am cold even in my down jacket?” He said, “Oh, it is easy dear. In Tibet we learn this meditation. It keeps us warm. And it is very necessary in cold weather!” Having been plagued by the cold my whole life, I thought, whatever it is, I want to learn it. (Later, when I read Lama Govinda’s “Way of the White Clouds” I would understand that he was talking about Tumo meditation. He did teach it in the last teaching I would receive from him at Vajrapani when he taught “The Six Yogas of Naropa”.)

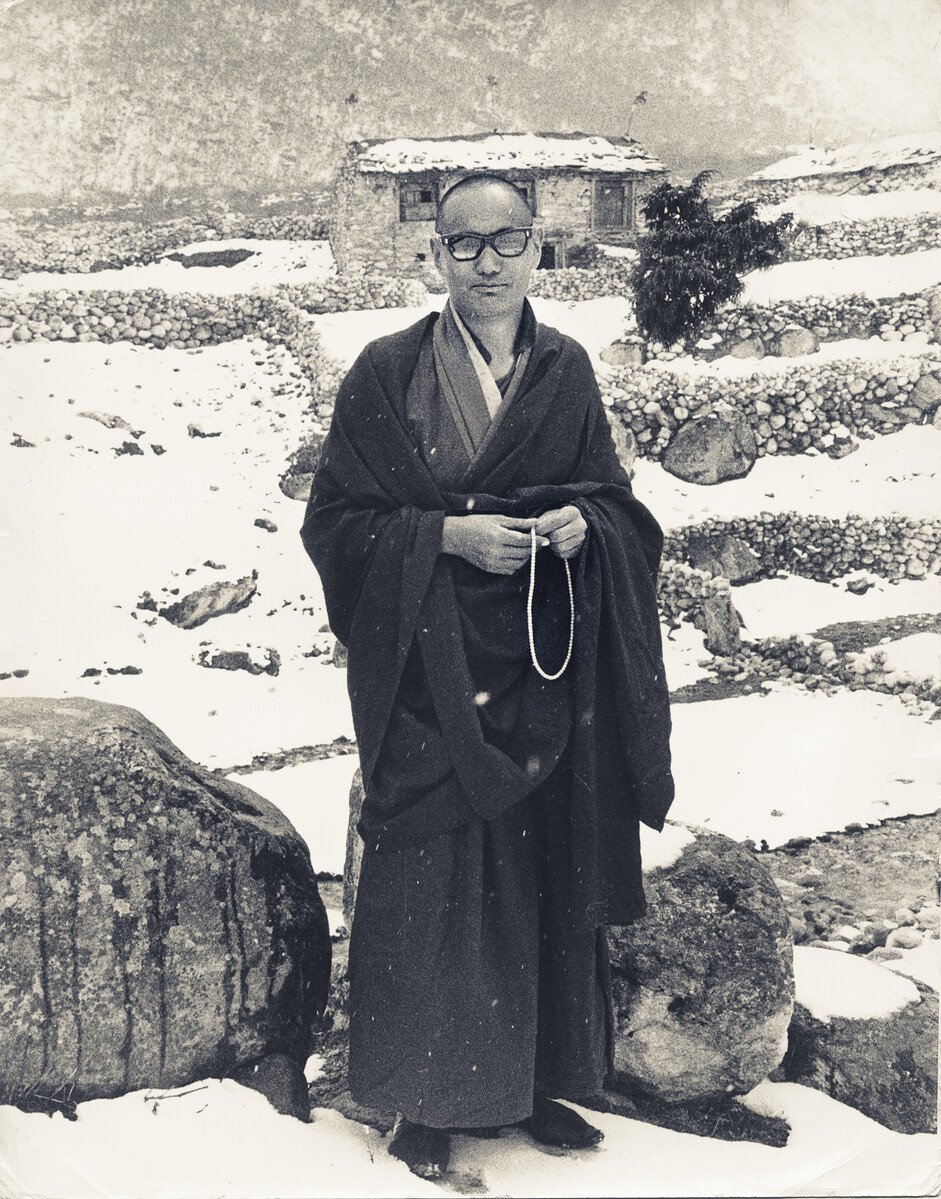

Lama Yeshe at Thangme, Nepal, during the first trek to Lawudo, Spring of 1969. Photo by Georges Luneau.

The next thing that happened is really hard to believe, but, I swear it happened. Lama was carrying a canteen with cold tea. (Each night, we would fill our canteens with the leftover tea from the evening before to drink during the day.) He asked if I would like something to drink. I said, “yes, I would, but not tea”. “What would you like, dear?”, he asked. I grumpily replied, “a Coca-cola” At the time there was no Coke in Nepal and there was no way he could have even known what I was talking about. The remark was meant as a joke for Max. He poured some liquid out of the canteen and gave it to Max. Max said, ”Look, Judy, it’s Coca Cola. Taste it.” I held it up and looked. It was carbonated. Bubbles were moving up the side of the cup. I tasted it. It was Coke. We all laughed and laughed and I completely forgot about my exhaustion and my bad mood. It was there on that mountainside that I realized that Lama Yeshe was totally amazing and powerful.

On our first night in Namche Bazaar we stayed in two different guest houses. Zina (Rachevsky) and Jacqueline and the Lamas were a few houses away from us. They met the French filmmakers there. When Prinz arrived, he was walking slowly with a stick. He had caught a cold and it was going into his lungs. Actually, he clarified, it was going into his one lung. The other one had been removed. First, no skull, then no lung! Should this man be in the Himalayas? I wondered. Fortunately, we found out that there was a small hospital established by Sir Edmund Hillary not far away. We planned to take him there the next day.

Our party split up the next morning. Zina, Jacqueline, and the Lamas headed toward Lawudo. Lama Zopa would return to his birthplace for the first time since he was carried over the mountains as a small child to go to Tibet for his education. At the time Lawudo was restricted and you needed a special permit to go there. The rest of us headed to Khunde, which was on the way to our destination, Tengboche Monastery. We walked along a high ridge spotting a beautiful iridescent bird along the way. It was Nepal’s national bird. It was the only time I saw the bird except on postage stamps. What a country! A flag with the sun and moon, a national bird that was beyond belief beautiful, and…the Himalayas!!! I was transferring my allegiance to this remarkable place.

The Hillary hospital was staffed by a young couple, doctors from New Zealand. They examined Prinz and diagnosed pneumonia. He would have to stay there. That night we stayed in the beautiful gompa room of another Sherpa home in the village. We slept in their gompa facing an elaborately carved altar with many statues and texts. I felt privileged to sleep in this holy place. Through the small window we could see the sacred mountain, Ama Dablam. When we awoke the next morning and looked out, the landscape had been transformed with a covering of snow. We were going to have to take a lay over day and wait for the snow to melt.

Fortunately this would allow a visit for some of us to see the famous Yeti skull which is housed in Khumjung monastery. I was told by some Sherpas that there were actually three kinds of Yetis – small ones who are vegetarians, medium-sized who eat small animals and big ones who eat yaks and people.

Max (Matthews) and I stayed in the gompa room most of that day. We spent the time in a deep philosophical discussion about the meaning and purpose of our lives. I was reading Alan Watts’ book, “East meets West” which prompted a discussion about Eastern and Western philosophy and our good fortune in meeting the Lamas. It was a magical time deeply imprinted on my mind…looking up at the benevolent gaze of the Buddhas, wondering about the contents of all those beautiful silk-wrapped books. Max and I truly became “Soul Sisters” that day. I felt it was a turning point for both of us. Max wanted to change the direction of her life. Till now my study of Eastern philosophy had been merely an intellectual pursuit. I felt my heart opening to a deeper level.

Max Mathews in a photo from the first trek to Lawudo Retreat Center in Nepal, spring of 1969. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

We were up early the next morning. We knew it was going to be a hard day. When we reached a view point above the valley, the Sherpas pointed out where we would walk: way, way, down to the river and way, way, up the other side. I thought, “no way am I going to be able to walk that far in a day.” Every muscle in my body was sore from the previous day’s walk, but on we went. That day I really began to understand the workings of the human body – things I had taken for granted before – the need we have for oxygen and food for fuel. When we got down to the river, I was about spent. I had discovered that going down is not really easier than going up and that “Sahib’s knee” (the sore knee that inexperienced trekkers get) really happens on the way down. We had a few bars of pemican with us and I ate one. I could feel the renewed energy from the food. It’s funny, but I had never associated eating much with fueling the body for work.

I started up the other side, quite slowly. We were going to a higher altitude than we had been before. Gradually, I became aware that I was running out of oxygen, another thing I had always taken for granted. I had to take several breaths to get enough oxygen to take a few steps. I was moving so slowly that one of the Sherpas came back to help me. He wanted to pull me along with a belt. I didn’t want to move any faster than I was, because each step up meant less oxygen. We compromised finally, with him giving me a bit of a hand, but progressing more slowly than he would have liked. When I finally made the top, everyone else was there and had found lodging in a stone hut at the far end of the village. Mt. Everest was straight ahead with the plume of snow that always blows from the top. The Sherpas call it Chomolungma – Mother of the World, which to me is a more fitting appellation. We were surrounded by magnificent peaks. Each seemed to have its own presence, its own emanation. Indeed they are sacred and deserve our deepest respect.

Tengboche monastery was to our left. The view was vast. Gradually, I adapted to the altitude and could actually walk around without huffing and puffing. We spent a couple of nights there, hiking toward Base Camp one day and visiting the monastery for a blessing on the next. In the doorway of Tengboche I noticed that the same “Wheel of Life” drawing was at the entrance as I had seen at Samyeling Monastery near Bodhanath. I was curious about what it meant. It took several years to patch together the meaning of all the symbols in that amazing drawing. Now there is a book about it, but then I learned about it in bits and pieces when I had some time with a monk or a lama.

The way back to the Hillary Hospital was much easier. We were losing altitude rather than gaining, and my stamina had built up to the point where I could get up and walk for the day without too much problem. It was a real breakthrough for me and my body: to know that I could walk as far as I needed to go and that it didn’t matter whether it was up or down, it was all the same. I felt stronger and more in charge of myself than I had for my whole life. There was way more to this trek than what we saw along the way. For me, it was an incredible integration of body, mind and spirit. I knew I had the strength to do what needed to be done.

Prinz was on the porch of the hospital waving and smiling and looking way better. Thank God for antibiotics. Thank God for Sir Edmund Hillary’s kindness. And here was another amazing karmic incident. The doctors excitedly told us that they had an old x-ray machine that had been donated to the hospital. It had never worked and it was so old they had no idea what to do with it. It turned out that Prinz had driven an ambulance during the war and served as a medic. He was totally familiar with this type of machine, and without hesitation, he made the repairs. (Can you imagine – repairing the x-ray machine, so they can look at your lung?) Not long after they had tested it out on him, a Sherpa walked into the hospital who had fallen off a mountain. They used the machine to diagnose the extent of the damage and found multiple fractures, arms, legs, ribs, everywhere. The miracle was that the Sherpa was so muscle-bound that his musculature was holding the broken bones in place. He was his own cast. That is how he could walk in with all of those fractures. We left Prinz and his assistant behind as he needed a few more days of recuperation before getting to work on his book.

When we arrived back at Namche, it was like coming home to a familiar place. At that point, Chip decided he had to try to go to Lawudo. He just took off down the trail without a permit and said he would be back the next morning in time to leave for Lukla and to catch our flight out. He was flying along the trail and right past the guard station. The guards chased him for a while but gave up. He was moving too fast.

Max and I were waiting back in Namche for him to return. I was getting very nervous. We had to leave by a certain time to make it to Lukla to catch our plane back to Kathmandu. Chip came back late. He was so excited about his experience in Lawudo – going to the cave belonging to Lama Zopa’s predecessor and seeing Lama Zopa and Lama Yeshe make themselves at home there. He had helped open the door by wriggling underneath the entrance. The whole village had turned out for the opening of the meditation cave.

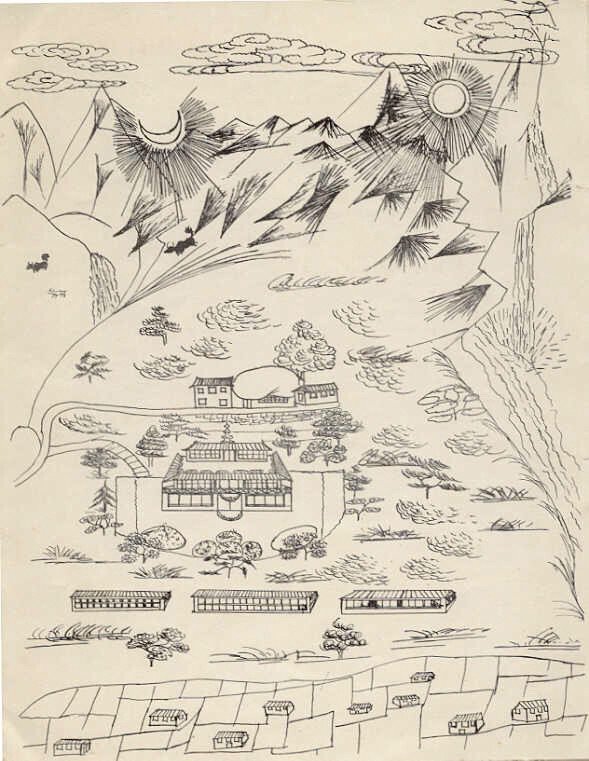

Lama Zopa Rinpoche (center) blesses a mother and child as Lama Yeshe looks on at at Thangme. Photo from the first trek to Lawudo Retreat Center in Nepal, spring of 1969. Photo by Georges Luneau.

Chip carried a note from the Lamas to Max and me. They said that they were going to stay in Lawudo and do some retreat, so we wouldn’t be seeing each other for a while. They also asked if Max and I could work on establishing a school for the children in the Lawudo area. Pieces of the puzzle were coming together. We finally understood that the people of the village had come to Lama Zopa when he was in his previous body, meditating in the cave, and requested that he start a school for their children. There was no school in the area, and, if they wanted an education, children had to be sent to Tibet or down to Kathmandu. The old lama said that he was too old and was going to die soon, but that he would do it for them in his next incarnation. Now, Lama Zopa was back and it was time for fulfilling the promise. Really, this was the first I had heard of promises being made in previous bodies or lifetimes. It was all very far out, but my skeptical mind was relaxing and allowing for possibilities that I would have questioned before.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche artwork, brochure for MEC school at Lawudo, 1969. Image courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

At Lukla, we bid farewell to our Sherpa guide, Ang Dorje. I felt so grateful to him for taking good care of us. I wrote a letter of recommendation on a scrap of paper and explained that he should show it to future trekkers to obtain jobs. Many years later, a friend who went trekking told me that they hired a Sherpa who carried a barely readable note from me. It had to be Ang Dorje. I was glad that gesture had served him well.

We waited in Lukla for the Arizona Helicopters plane. There, we were told that the King’s plane had returned on another run the same day we arrived. Maybe they were delivering the cargo that we refused on board. This time the pilot undershot the runway. The landing gear hit the mountainside and the plane crashed. Fortunately, no one was hurt. The plane was later towed by yaks up the runway to Lukla and converted to a Tea house, I heard.

I couldn’t believe how the STOL plane landed. It just flew directly in, without all the spiraling downward that we had done on our arrival. It hit the runway and stopped half-way up – no U-turn needed. The steely-eyed rough neck pilot got out, cussing and swearing. He was mad because we had a big Sherpa pot with us and it would put us overweight. We begged to take the pot with us, but to get the weight down, he dumped some fuel. He knew what he was doing, but the terror on the way back to Kathmandu, was watching the fuel gage tip toward zero as he swore at us and told us that if we ran out of fuel it was our fault for insisting on bringing the big copper pot.

Max, Chip and I returned to teaching and I began to ponder how we might start a school in the High Himalayas.

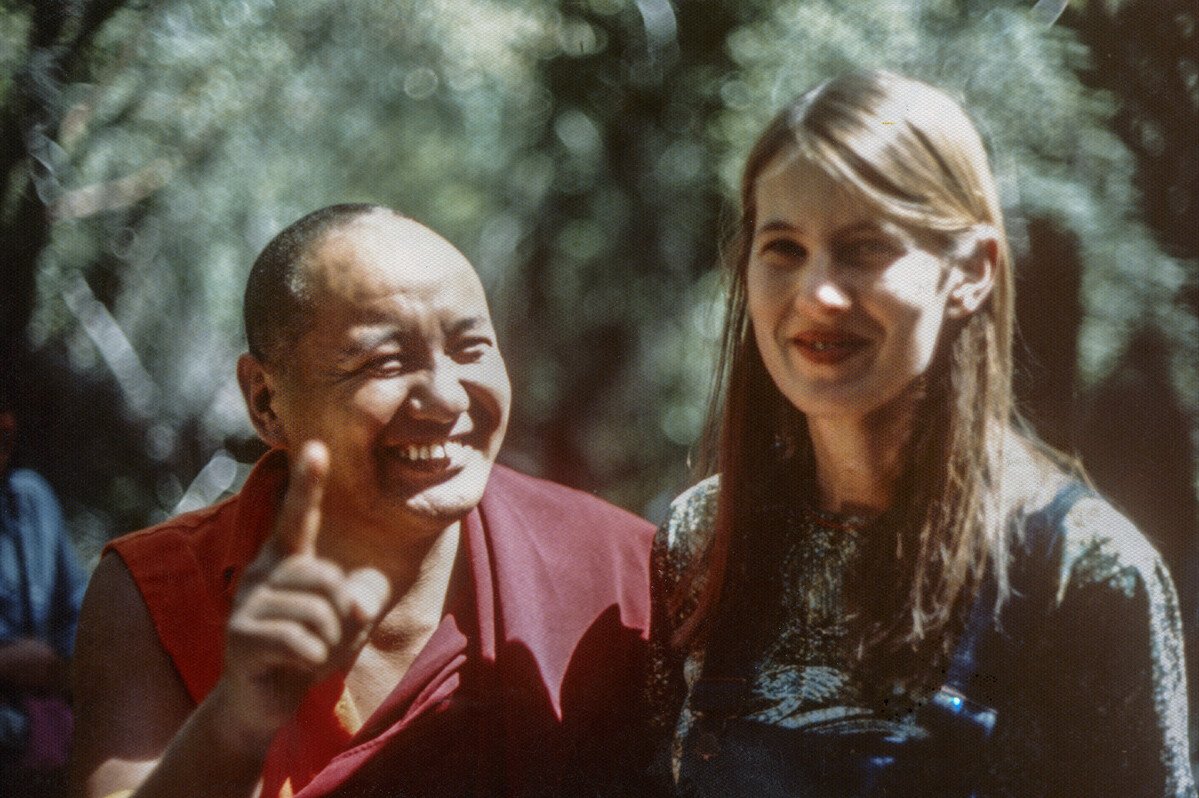

Lama Yeshe and Judy Weitzner on the land of Vajrapani Institute, CA, 1977. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Please consider subscribing to the Lawudo newsletter which is published four times each year on the major holy days. For more information about Lawudo Gompa and Retreat Center, please visit the Lawudo Gompa website. You can also follow Lawudo on Facebook.

FPMT.org brings you news of Lama Zopa Rinpoche and of activities, teachings, and events from over 150 FPMT centers, projects, and services around the globe. If you like what you read, consider becoming a Friends of FPMT member, which supports our work.

- Tagged: lawudo, road to kopan, ven. margaret mcandrew

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.In my mind, one of the beauties of Buddhism is that it offers us a practical training for our mind. It does not say, ‘Bodhicitta is fantastic because Buddha said so!’ Instead, it gives us the methods for developing such an attitude and we can then see for ourselves whether it works or not, whether it is fantastic or not.