- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

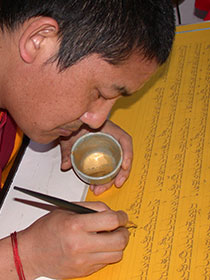

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

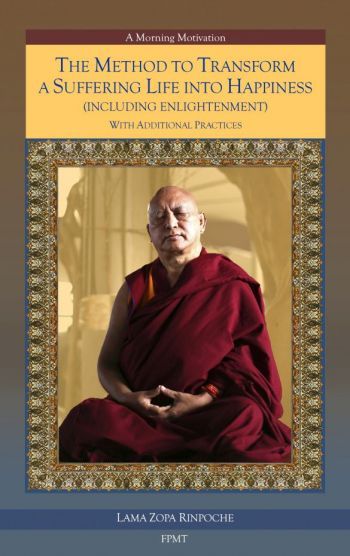

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

True religion should be the pursuit of self-realization, not an exercise in the accumulation of facts.

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom

16

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Living in Awareness

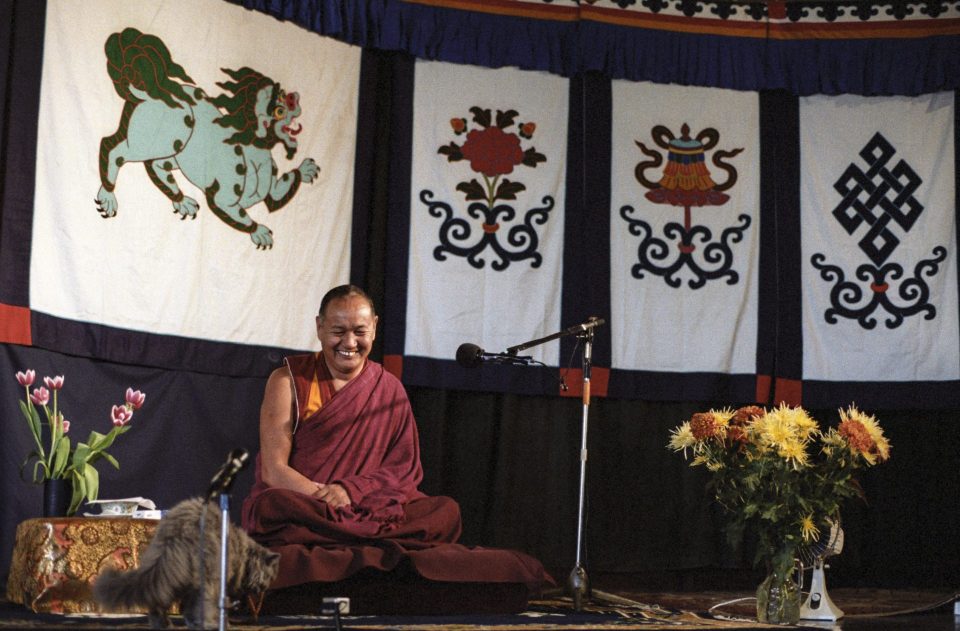

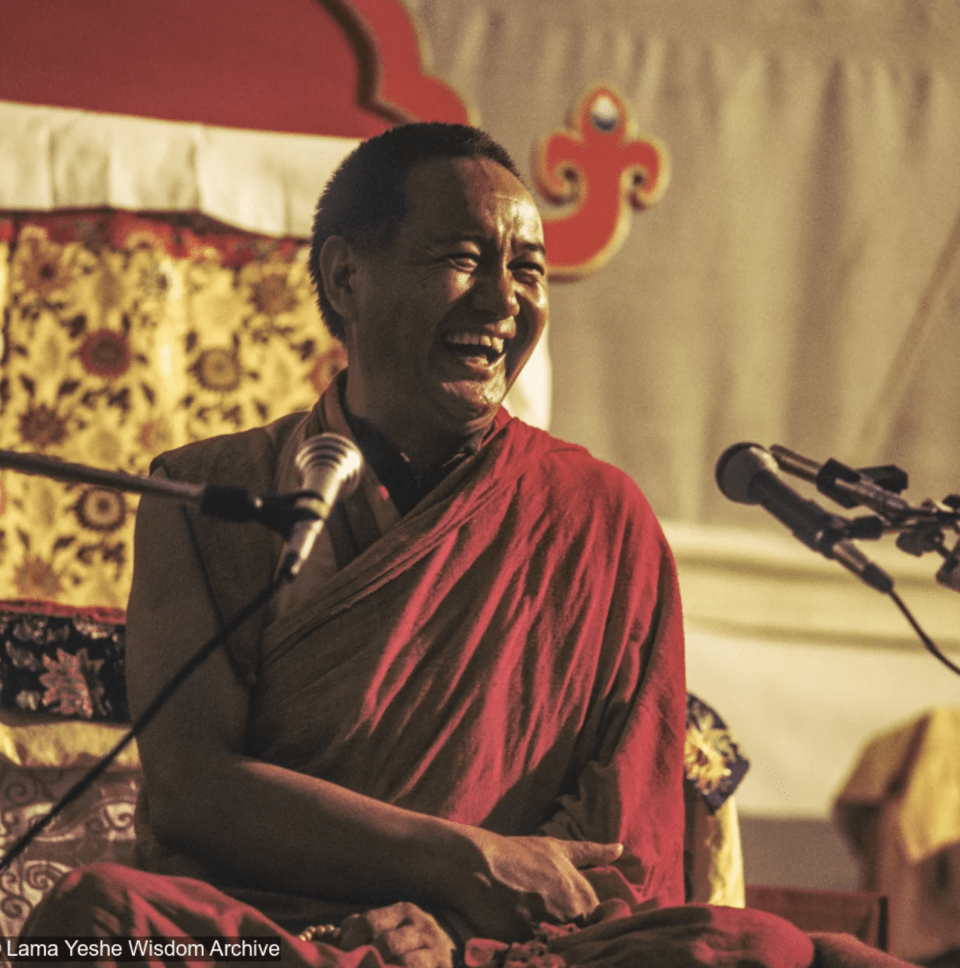

Lama Yeshe teaching in Ibiza, Spain, 1977. Photo by Francois Camus (donor), courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archives offers a growing index of teaching excerpts from Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe. In addition to the fascinating historical narrative from students of Lama Yeshe, Big Love is also filled with Dharma teachings. Here we share an excerpt from a teaching by Lama Yeshe on the importance of cultivating mindful awareness in our actions and a clear understanding of karma, in Ibiza, Spain, October 1977. This teaching is published in Chapter 16 of Big Love:

The lamrim actually teaches us that everything we see—on the television, the wind blowing, the movement of the ocean—all these are a teaching on karma. The lamrim teaches reality. Time is changing. Summer changes to autumn, autumn changes to winter and winter changes to spring. All these changes, all this movement shows the impermanent nature of reality. We should learn from these teachings that the world brings us constant change. In the same way that these things change, so do I. We haven’t yet understood this. We should understand that every movement that we see, every movement that exists in the entire world is showing you reality.

When we watch something on television, we see it as a fantasy. Instead of seeing it as presenting the evolution of cause and effect, we are shaking with fantasy and become even more deluded. Are we communicating? But if we have Dharma wisdom, when we watch movies or television, we see that these are showing us cause and effect in the evolution of samsara. Unfortunately, we aren’t generally able to see actual reality. We only see things in a polluted way, and so we become more deluded.

Every movement of karma has a reason. Every movement of karma is connected, is an evolutionary link. If you understand that, you understand karma. Your mind transforms, your body transforms, your nervous system transforms; they are all changing, changing, changing. You can see karma. And when you can see karma, then you are aware of your actions—what you are supposed to do, what you shouldn’t do. You have some control of your own mind. You become more discriminating with regard to your own behavior. Then it becomes the practice of Dharma. If you are unconscious about your own actions, if you don’t know what you are doing, then there is no way you can see what action brings what result. Not being able to see clean clear which results come from which attitude or action is actually a cause of your continuing ignorance. That is not Dharma practice.

Being mindfully aware of all your own actions throughout all the hours of the day, from the time you get up in the morning until you go to sleep—that is even more profound than doing some kind of meditation in the morning. The reason I’m saying this is that Western people are so interested in meditation. They love meditation, love to talk about meditation, but they don’t love it when Lama explains karma. Karma is strong, strong. “Karma is … well … that’s too heavy for us!” But our body, speech and mind are heavy already. It’s not your lama who makes them heavy. They are already heavy. This is why understanding karma is very important. Meditation is OK. But even if you are unable to meditate it’s all right. My meditation is that as much as possible I try to be aware of my own actions. I dedicate my day as much as possible to other people. Whatever I am involved in I try to have loving kindness and be sympathetic to others and I try not to take advantage of others as much as possible. This is my meditation. I observe my own body and speech; this is my meditation. Actually, that is more precise and realistic than, “Oh, I’m meditating on tantra ….”

This is a very simple thing. Today, even though we are here, our mind is not actually living here. Already we are thinking, “After the course I’ll … blah, blah, da da da ….” Our body is here but our mind is already in the future, after the course, not living in the present, not living in the moment. We never pay full attention to each other in this present moment. For example, while I’m talking to you people, my mind is thinking of Tibet. I’m not with you. This is wrong! Each day, when you get up in the morning, remember, “Today I am alive. How fortunate that I am alive today. I can do much better than dogs or chickens because I have the power of being human. I have better understanding. So, as much as possible today I’ll be aware and keep my body, speech and mind clean clear. I will communicate a good vibration to sentient beings and dedicate my life to reaching the highest destination—enlightenment.”

By generating this dedicated attitude in the morning, by the power of your mind you bring great space to your day. In this way the power of your mind keeps you from becoming angry. By living in an awareness of the present moment, it brings a kind of total relaxation, rather than fooling yourself.

Lama Yeshe gave this teaching in Ibiza, Spain, October 1977. From Chapter 16 of Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Subscribe to the LYWA monthly e-letter and keep up with the latest news and publication information.

- Tagged: big love, lama yeshe

20

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: A Simple Explanation of Karma

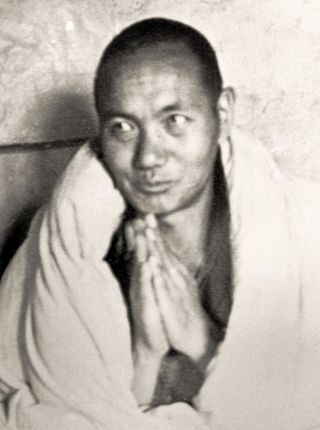

Lama Yeshe teaching at Manjushri Institute, England, 1976. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archives offers a growing index of teaching excerpts from Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe. In addition to the fascinating historical narrative from students of Lama Yeshe, Big Love is also filled with Dharma teachings. Here we share an excerpt from, “A Simple Explanation of Karma” from Chapter 14 of Big Love:

You can explain karma in many different ways. For example, it can be explained academically, with many divisions and analytical points of view. But right now I am going to give just a simple explanation.

Karma means action; actions of body, speech and mind are karma. For example, we have just recited, “I take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha; I will follow the Dharma.” But if we are not conscious in our everyday actions of body, speech and mind I think it is difficult to really take refuge.

Taking refuge cannot solve your problems if you are not aware of your own actions. Even though you believe “Buddha is fantastic; Dharma is fantastically pure; Sangha is fantastic. They are perfect; I have no doubts,” that is not enough. It is not enough to say, “OK, I understand from meditation, books and lamas that Buddhadharma is perfectly clean clear. I know now that this is my path.” If you live that way rather than being aware of your own actions, refuge cannot solve your problems. Real refuge is saying and doing things according to the motivation of refuge in your mind, and that is karma.

Karma means that you act in a certain way with a certain motivation and some effect arises within you. Karma can be positive or negative. Actions that bring a positive reaction are called morality; actions that bring a negative reaction are called immorality. Whatever action—or we can call it energy—of body, speech or mind that brings confusion, restlessness, sorrow or suffering is immoral. So, as much as possible, we should try to understand Lord Buddha’s teachings, which say that certain actions are moral and certain actions are immoral because they bring good or bad reactions respectively.

Understanding this, in your everyday life you should try to make your actions as positive as you can. Try to understand, “If I think this way and act this way, what kind of result will it bring?” Knowing this is very important. Also, karma is not something that you just believe. Your entire energy since you were born has been related to karma. The existence of karma is not dependent on whether you believe it or not.

For example, maybe you say, “I don’t believe in karma. I don’t believe in anything. There is no such thing as karma making me happy or unhappy.” No matter how much you are against it, your entire being, your saying this and thinking that—it is all karma. No matter how much a person may be against Lord Buddha’s idea … it doesn’t matter. The entire person, both psychologically and physically, who is tick, tick, ticking like a watch—all that is karma. Therefore, karma is just the energy of your body, speech and mind. The human body, speech and mind are karma.

The meaning of karma includes cause and effect. Your entire physical and mental energy, everything is reacting and producing other actions, no matter whether you believe it or not. Some Western people think, “Well, if I am Buddhist and I believe Lord Buddha’s idea, then I have to be careful; if I am not careful I will get bad karma. But if I do not believe, it doesn’t matter.”

Many Western people think like this; in my life I have heard some people say this. It is not like that. Karma does not depend on whether you believe it or not. It doesn’t matter if you believe; it doesn’t matter if you don’t believe; it doesn’t matter even if you reject. Karma is talking about natural scientific law—that’s all. Natural scientific law—how can you reject that? It is not something Lord Buddha made up.

Also, there is some confusion around Eastern words. The word “karma” is Sanskrit. When one says “karma,” you say, “Oh, karma is Eastern stuff.” You cannot say that. All of you is karma. You are karma; you cannot escape from karma. It does not matter if you follow another religion, if you are a Hindu, if you are a Christian, if you are a believer or a non-believer, you are completely immersed in karma.

That is why karma is very heavy. You cannot say, “I don’t believe in suffering.” It does not matter whether you believe you are suffering or not—you are suffering. Your suffering is not dependent on whether you believe in it or not.

Now, you can see through your own meditation experience how the mind is continually circling around—whooooshhhhhh. You cannot stop your mind from running around—one thought, then another thought, and another thought, and another … phew! Incredible! This is karma, the uncontrolled thoughts running, running like a watch. Without understanding the activity of our body, speech and mind we will not understand how to generate a positive or a negative lifestyle. Even though we have tremendous belief that “Buddhadharma is my way,” we are still joking.

The simple way to live positively is to examine the everyday actions of your own body, speech and mind. As much as possible be aware; what we call morality is putting the energy of body, speech and mind in a positive direction. But in the West, morality and immorality have religious connotations. There are some funny ideas, such as the belief that morality is something made up by religious people. No! Morality is not merely a religious idea; it is not some philosophical creation. Morality is about nature.

Scientists explain natural things—organic, inorganic, the evolution of human beings, fish and monkeys. This is all taught at school and you learn these things. From Lord Buddha’s point of view, karma is closer to the things you learn at school. In school they try to teach you as scientifically as possible: “This is exactly like this, then this comes, then this, then that,” and so on, the mathematical way. Karma is similar.

Actually, if you are aware of how your own body, speech and mind are running, the evolution of your everyday life is similar to what you learned at school. When you understand karma you will see how greatly effective just one small action can be. For example, when Lord Buddha once explained karma, he used a bodhi tree seed as an example. Do you know the Bodhi Tree in Bodhgaya? It is huge, isn’t it? He took a seed of the Bodhi Tree and said that by putting that tiny seed into the ground, the result would be a huge tree that can give shelter to five hundred bullock carts. That was Lord Buddha’s example: a small seed can produce a huge plant. It is the same thing with karma. Especially the psychological effect, which is much greater than the external one.

In the West, some people think that karma is something simple, whereas meditation is a profound and unusual contemplation where you become very high and feel, “I’m happy …” They think that is fantastic. Actually, according to the lamrim, meditation is not the most important thing. What is extremely important is to maintain awareness of your everyday life actions. Be aware of your own actions and put your actions on the right track. Then you will begin to experience an incredible effect.

From Chapter 14 of Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Subscribe to the LYWA monthly e-letter and keep up with the latest news and ordering information.

- Tagged: big love, karma, lama yeshe

20

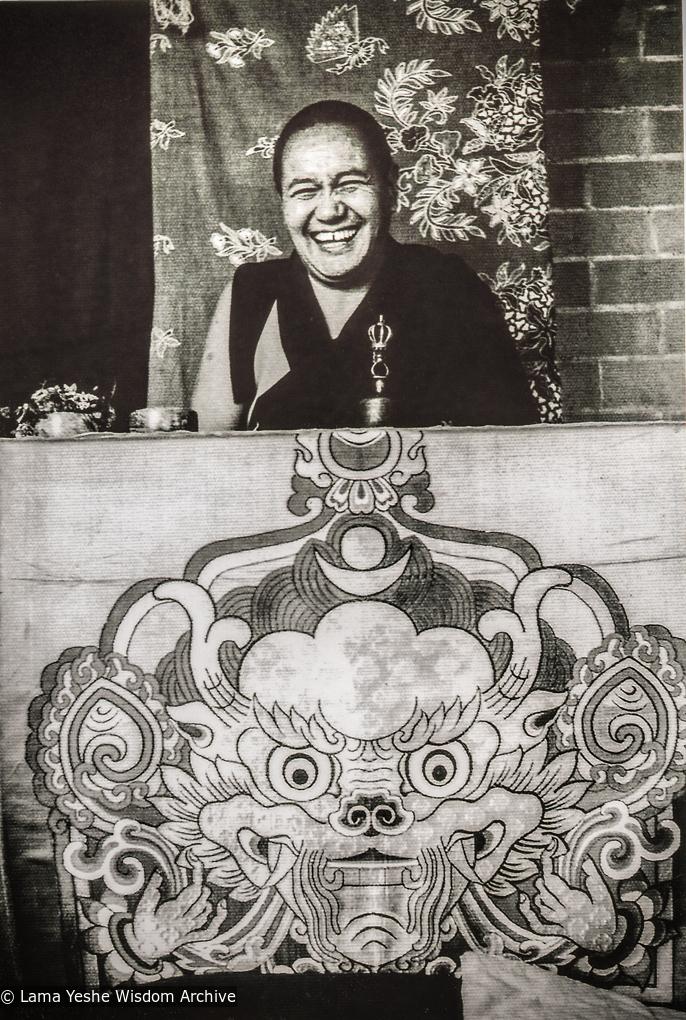

Lama Yeshe at Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa, Italy, 1983. Photo courtesy Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive, donated by Merry Colony.

In 2025, Lama Yeshe would have reached the age of 90 years. To honor his profound legacy, Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa (ILTK), Italy, invited his students from across the globe to share their treasured memories and life-changing teachings with present and future generations. A special puja was held on May 15 at ILTK celebrating what would have been Lama’s birthday.

Carlota Pinhero shares the story:

Lama Yeshe

May 15, 2025, marked what would have been the 90th birthday of Lama Thubten Yeshe. Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa gathered to celebrate his impact on countless lives. With profound gratitude for his jewel-like teachings available in these challenging times, we reaffirm our commitment to manifest Lama Yeshe’s vision through our actions and practice. He consistently emphasized cultivating a sense of family within the FPMT community. Honoring this wish, we gathered as part of this international family united in dedication to the Dharma and the ultimate welfare of all sentient beings.

Lama Yeshe was the beginning of the transformation of the minds of many westerners; the eye-opening key to the freedom that is possible to achieve in ourselves; the pointer to how all the suffering we’re experiencing is created by nothing but our minds. As his previous incarnation, abbess Achè Jampa, prayed over and over again “May I be able to bring the Dharma to those who have never met it and who live in suffering, their wisdom eyes are blinded by the darkness of ignorance.” And that is what Lama did! Lama Yeshe lived in a time of cultural revolutions and joked about his own revolution, the “Dharma Cultural Revolution.” He inspired and continues to inspire countless people to truly investigate what it means to be a human being.

As we have been conducting the interviews with his earliest students to celebrate 90 years since his birth, new ways of viewing reality have been unfolding, just by merely listening to Lama’s words through the mouths of those who were once very close to him, just as if he was here speaking himself. The way Lama shaped people’s lives and completely changed them from very negative states to very happy ones, is unique in this world. Even those new to Buddhism can feel his influence so present here in the center. Lama Yeshe knew how to deeply love each individual, listening attentively, healing without judgment and even smiling at the shadows of the mind. His “Big Love” gave new light to those blinded by ignorance. His faith in human potential brought many students to believe in themselves and bring a positive impact to the world.

Community Celebration of the 90th Anniversary of Lama Yeshe’s Birth

The altar at ILTK for the Lama Yeshe ninetieth birthday celebration. Photo courtesy of ILTK.

Cleaning Lama Yeshe’s Stupa

As the sun reached its zenith, a small group of us gathered in the gardens of ILTK, around Lama Yeshe’s sacred stupa, built many years ago as a testament to his enduring presence. Volunteers, intrigued by our festive environment, would go by and join us. This stupa has been a silent witness to the full spectrum of human emotion; from the grief of his passing, to the excitement of a reincarnation, and now hundreds of people each week come to circumambulate it, walk their pets, or encounter the Dharma for the first time during retreats.

Geshe Lhundrup guiding and cleaning Lama Yeshe’s Stupa, ILTK, Photo courtesy of ILTK.

With a screwdriver in one hand and silicone in the other, clothes and sponges at the ready, we began chanting mantras while spending the next four hours meticulously cleaning every sacred detail of the stupa—polishing the ornate silver that frames Lama Yeshe’s image and the Buddha seated within, removing the weathered cloths and offering it fresh khatas and flowers. Geshe Lhundrup, a monk from Kopan now resident at ILTK, and Thubten Sherab, raised by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, spent the day guiding us on the best way to do this. The sun was shining the whole afternoon, and the environment felt exactly like what we are here to do in this life: work with intention, remain aware of our actions, rejoice and help each other in whatever ways we can.

There is something special about coming together as a community to honor one’s teacher, to honor the legacy that allows us to be here today, working on our afflictions and, together, discovering how to cultivate happy minds and a happy family. This was Lama’s wish. In 1978, visiting ILTK, he said, “Each one of us can become a disaster when we go through difficult times, so we must try to help each other.”

Guru Puja

The day culminated in a special Guru Puja with a beautiful cake inscribed with “Big Love” at its center, offered by ILTK president, Lucia Landi, and director, Valerio Tallarico. The gompa was filled with practitioners, including some of the direct students of Lama Yeshe who shaped the center into what it is today. For him, ILTK had the function of being a refuge: “It has to be friendly, because everything is dedicated to sentient beings.”

Big Love cake offered during the puja. Photo courtesy of ILTK.

The puja was conducted by Geshe Gelek and, in the end, some of Lama’s first students shared memories and funny stories, among them, Massimo Corona, founder of the Institute, former executive director of FPMT International Office, and former publisher of Mandala magazine; and Susanna Parodi, who, in the words of Lama, was, “the first lady on this earth to become Italian Mahayana Buddhist nun.” Voices united in chanting and in gratitude as we spoke about the true source of it all: The boundless compassion of our precious Lama.

Lama Yeshe joked, “There are three types of Buddhism: Hinayana, Mahayana, and Italiana!” He made this comment due to the unique passion and distinct attitude of the first Italian students. It is also thanks to this dedication that the Institute is one of the biggest in Europe and one of the doors through which the Dharma continues to spread around the world.

Direct Students Interviews

Throughout 2025 ILTK will be interviewing Lama’s direct students to share how his teachings impacted on their lives through short video. These interviews will be treasured and shared through the Institute’s social channels and with the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Massimo Corona speaking about Lama Yeshe and the origins of ILTK. Photo courtesy of ILTK.

Listening to the stories of those who had their minds completely transformed by Lama Yeshe and feeling this strong sense of family, devotion and, above all, deep gratitude, is deeply inspiring and has sparked the wish of keeping his legacy in any way possible. The way future generations can, especially now, benefit from his teachings, his timeless wisdom and compassion, is inconceivable. This is what the path to enlightenment is, caring for our own minds and also caring for this rare family that we build through our devotion to the Dharma and the lamas, from the single intention of leading all beings to a state free of suffering.

If you wish to help keep Lama’s legacy alive for the future generations, and were fortunate enough to have known Lama Yeshe, please consider taking part in the project 90 Students for 90 Years. If interested, please contact ILTK directly. The short video interview series will continue through 2025.

All quotes shared here are from Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe. With grateful thanks to Carlota Pinhero and Fabiana Lotito for this story.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: lama yeshe

16

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Defeating the Eight Worldly Dharmas

Lama Yeshe teaching at Kosmos Centre, Amsterdam, 1980. Jan-Paul Kool (photographer) Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind is the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings, forthcoming in May 2025 from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. This book contains introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

Here we share an excerpt of Lama Yeshe’s teaching from Chapter 13 of this book, Defeating the Eight Worldly Dharmas:

The attitude behind the eight worldly dharmas, or phenomena, is a symptom of ignorance and ego and we have to recognize it as a negative motivation. For example, if you have the attitude that receiving a present is a source of pleasure and not receiving one is a cause of unhappiness, that’s not good. That attitude is a symptom of ego.

First of all, this attitude does not understand what is a gift and what is not. It functions at a very gross level. You don’t understand the broad view that the gift of other sentient beings is profound. If you think that giving chocolate is the only way to interpret giving—if you’re not giving chocolate, you’re not giving—your view is extremely narrow, and that’s a problem.

Another of the eight worldly dharmas is being attached to pleasant feelings and averse to unpleasant ones. That’s not good either. For a start, the way in which you interpret pleasant and unpleasant is completely relative; it depends. For example, one person considers meditating to be like going to a nightclub or the beach and finds it really enjoyable, while another considers it to be like being in prison and completely miserable. So, finding certain situations pleasant or unpleasant depends on your attitude.

Secondly, taking responsibility for your own liberation and enlightenment is not an easy job. It requires much effort. To demonstrate this, Shakyamuni himself spent six years in indestructible single-pointed meditation without food or other necessities in order to attain his goal. That’s not to say you should punish yourself in that way, but it’s a matter of putting right livelihood into the right channel, skillfully putting your body, speech and mind in the right direction, from peaceful environment to peaceful environment, which is, in fact, the path to enlightenment.

I say that following the path to enlightenment is not an easy job because our wrong conception mind, our grasping attitude, always overwhelms, interrupts and interferes with our efforts, and dealing with all this disruption can be difficult. So we should expect to encounter obstacles when trying to follow the path.

Nevertheless, the Buddhist interpretation of negotiating the path to enlightenment is not that it should be a miserable experience. We should not think, “I’m a religious person, therefore I should suffer; I’m a religious person, therefore I should not have plenty of bread and butter and should feel guilty if I do. Look at the people in Africa; they don’t even have water.” That sort of ridiculous thinking just makes you depressed. Also, it’s not right. You should not make yourself emotionally irritated, confused or guilty. That simply disturbs your tranquility and peace of mind. Read more of Chapter 13, Defeating the Eight Worldly Dharmas.

From Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind, the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings containing introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Subscribe to the LYWA monthly e-letter and keep up with the latest news and ordering information.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: advice from lama yeshe, lama yeshe

28

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Meditation is Action

Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind is the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings, forthcoming in May 2025 from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. This book contains introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

Here we share an excerpt of Lama Yeshe’s teaching from Chapter 1 of this book, Mind and Meditation:

Meditation is Action

If you cultivate your mind in meditation, it becomes sharp and clean clear and you can easily see your false conceptions. This is extremely difficult to do when you are deeply submerged in hallucination, just as it’s extremely difficult to surface when you’re trapped deep in the ocean. At the beginning, when you’re full of wrong conceptions and garbage thoughts, it’s hard to distinguish between right and wrong. Extremely difficult. Therefore, meditation is so worthwhile. Its result is that it integrates your mind and allows you to understand your own actions, which mostly arise from misconceptions and lead you into a restless state of mind.

Through meditation you can also see your great potential and understand that there’s no value in just living for food and clothing. It’s so sad to see people living only for food and clothing, ignoring their great potential. That’s incredibly sad, isn’t it? Living for such small temporal pleasures, which have no real value and do not last. Sometimes, if we really check up, we’re too much; it’s incredible.

What we need to do is to compare the worldly pleasures that our wrong conceptions believe will make us happy with the benefits of meditation. In the West we have hundreds, even thousands, of ideas of what makes us happy, not just food and clothing. Look at supermarket shelves. There are so many ideas. Most of them are wrong conceptions. Through meditation you can discover those temporal objects have little value; actually, no value. I don’t mean you should completely reject them. Don’t reject them, but if you strongly desire them and put too much energy into them, it’s just not worth the effort. Especially when it comes to material objects, which are so unreliable. When you need them, they’re not there; when you don’t, they are. Sometimes they’re there, sometimes they’re not.

Consider medicines, for example. They are there to help us, to support and sustain life, but we can never be sure whether they’ll destroy our life or preserve it. It’s not certain. Through meditation, however, we can discover joy and the everlasting, peaceful state of mind, and that understanding can last forever—from this life to the next and to all our future lives. By comparison, material things can disappear in a flash, and at the time of death we leave everything behind. Not only that; we die with great attachment to our material possessions, and that brings us much harm. It’s not the material objects that harm us but our clinging to and grasping at them. During our life we grasp at this, we grasp at that, building up our attachment more and more, so that when we die, our grasping is incredibly strong and very difficult to release. During our lifetime, our desire wants more and more, such that we build up more and more superstition, which makes us more restless, more confused, more foggy and more ignorant. Therefore, actualizing meditation is really worthwhile.

If you don’t contrast material things with meditation you won’t understand how much more worthwhile the results of meditation are compared with those of the desires of the sense world. If you don’t know that, you won’t have much energy for meditation. Being unsure, you won’t see that sitting down to meditate is of much greater value than running out for chocolate. Your attraction to chocolate will be stronger than your desire for meditation. It’s obvious.

I’m not joking when I talk this way. I’m saying “chocolate,” but I’m referring to the incredibly overpowering Western vibration for sense pleasures. It’s all so exaggerated, which just makes life much more difficult for Western people. So much clinging. I can see that. But at the same time, you people are very intelligent; you can see how shopkeepers and television advertisers in the West understand people’s psychology. Ask yourself, “Why are they doing this? Why are they doing that?” They’re appealing to people’s superstitions and delusions. You can see. Maybe you think I’m exaggerating but check up for yourselves. That is the really important point. Read more of Chapter 1: Mind and Meditation.

From Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind, the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings containing introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Subscribe to the LYWA monthly e-letter and keep up with the latest news and ordering information.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: advice from lama yeshe

18

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: First Teaching of Intro to Tantra

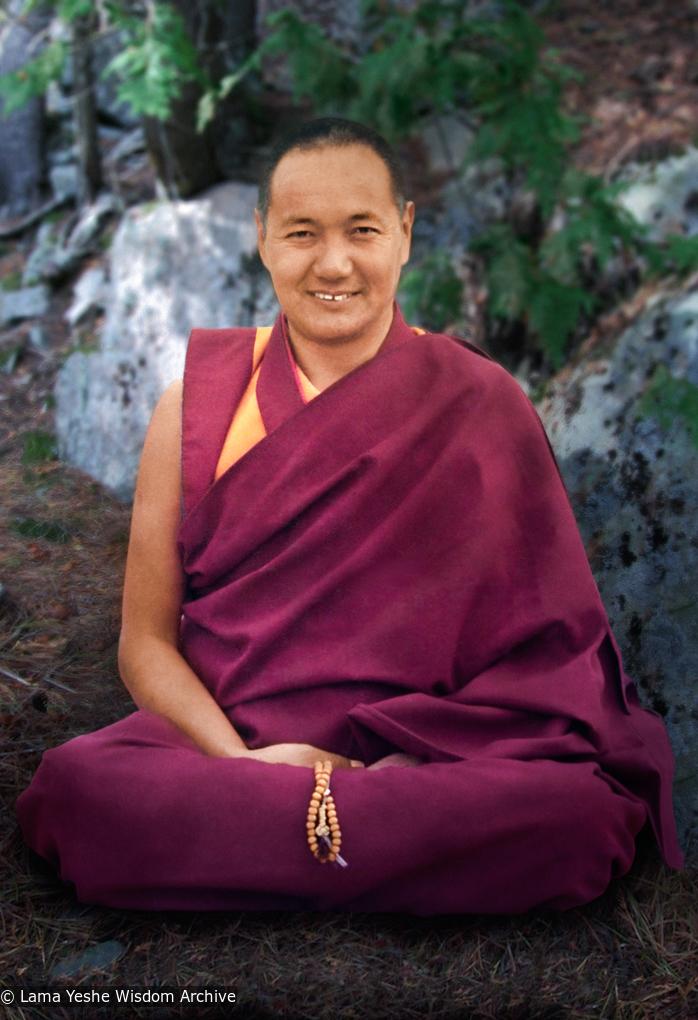

Lama Yeshe, Chenrezig Institute, Australia, 1975. Photo by Tony Duff, retouching by David Zinn. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Lama Yeshe gave a commentary to the Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig) yoga method at Grizzly Lodge, California, in May 1980. Here we share Lama’s introduction to this series, Intro to Tantra: First Teaching, which constitutes a wonderful explanation of the fundamentals of tantric practice. Please read an excerpt:

Philosophically, perhaps we can say that karma is overwhelming-consciously and unconsciously. Don’t think that karma is just your doing something consciously and then ending up miserable. Karma also functions at the unconscious level. You can do something unconsciously and it can still lead to a big result. Today’s problems in the Middle East are a good example. That’s karma. They started off small, but those little actions have brought a huge result. As a matter of fact, that’s karma.

In order to have the enlightened attitude, an attitude that transcends the self-pitying thought, you need the tremendous energy of renunciation of temporary pleasure-renunciation of samsara. I think you know this already. What do we renounce? Samsara. Therefore, we call it renunciation of samsara. Now I’m sure you’re getting scared! Renunciation of samsara is the right attitude. The wrong attitude is that which is opposite to renunciation.

You probably think, “Oh, that’s too difficult.” It’s not difficult. You do have renunciation. How many times do you reject certain situations, unpleasant situations? That’s you renouncing. Birds and dogs have renunciation. Children have renunciation-if they want to do something for which they’ll get punished, they know how to get around it. That’s their way of renunciation. But all that is not renunciation of samsara. Perhaps your heart is broken because of some trouble with a friend so you change your relationship. Anyway, your friend has already given you up so you have to do the same thing and renounce your friend. Neither is that renunciation of samsara.

Perhaps you’re having trouble coping with society so you escape into the bush, like an animal. You’re renouncing something, but that’s not renunciation of samsara.

What, then, is renunciation of samsara? Be careful now-it’s not being obsessed with the objects of samsaric existence or with nirvana, either. Perhaps some people will think, “Now that I’m not concerned with pleasure, now that I’m renounced, I would like to have pain.” That, too, is not renunciation of samsara. Renouncing the sense pleasures of the desire realm and looking for something else instead, grasping at the pleasures of the form or formless realms, is still the same old samsaric trip.

Say you’re practicing meditation, Buddhist philosophy and so forth and somebody tells you, “What you’re doing is garbage; nobody in this country understands those things.” If somebody puts the nail of criticism into you like that and you react by getting agitated and angry, it means that your trip of Buddhism, meditation or whatever is also samsaric. It has nothing to do with renunciation of samsara. That’s a problem, isn’t it? You’re practicing meditation, Buddhism; you think Buddha is special, but when somebody says, “Buddha is not special,” you get shocked. That means you’re not free; you’re clinging. You have not put your mind into the right atmosphere. There’s still something wrong in your mind.

So, renunciation of samsara is not easy. For you, at the moment, it’s only words, but the thing is that renunciation of samsara is the mind that deeply renounces, or is deeply detached from, all existent phenomena. You think what I’m talking about is only an idea, but in order for the human mind to be healthy, you should not have the neurotic symptom of grasping at any object whatsoever, be it pleasure or suffering. Then, relaxation will be there; that is relaxation. You don’t have superstition pumping you up. We should all have healthy minds by eliminating all objects that obsess the ego. All objects. We are so concrete that even when we come to Buddhism or meditation, they also become concrete. We have to break our concrete preconceptions, and that can only be done by the clean clear mind.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read this full teaching.

A video of Lame Yeshe giving this entire teaching is available:

This teaching is included in Lama Yeshe’s book The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. You can also view the talks on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive YouTube channel, listen to the audio book, or read the book online.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: advice from lama yeshe, lama yeshe

26

Lama Zopa Rinpoche Discussing the Qualities of Lama Yeshe

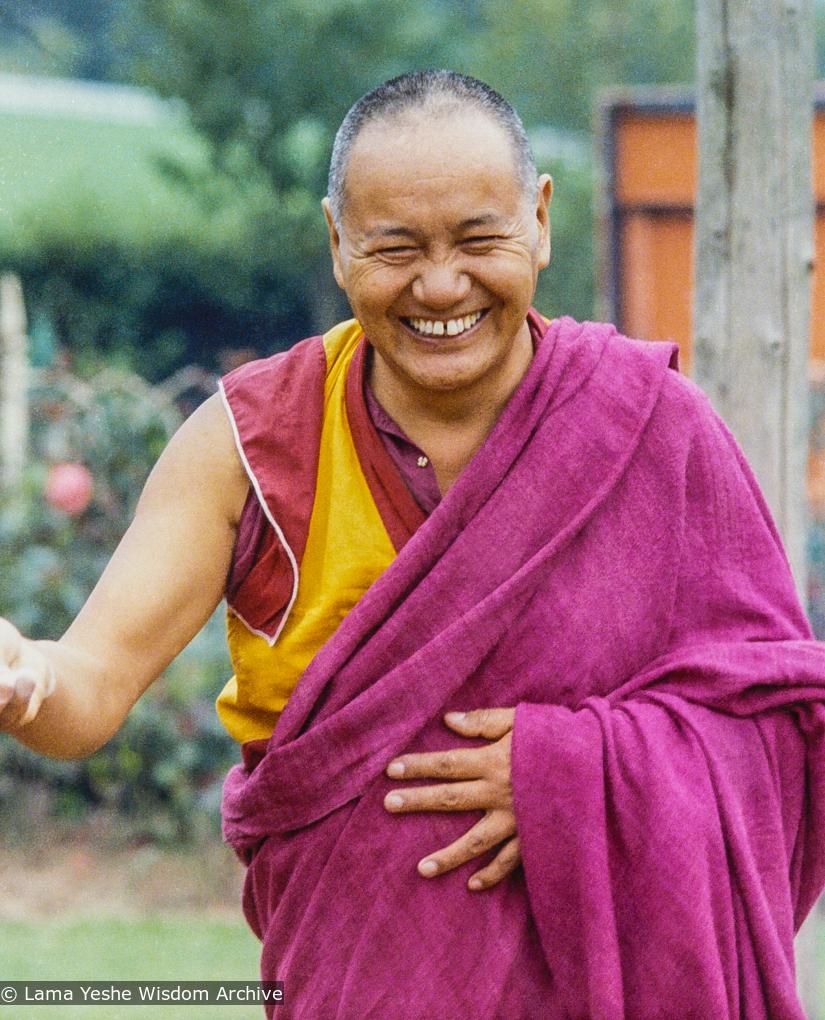

Portrait of Lama Yeshe, Manjushri Institute, England,1982. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Tibetan New Year, Losar, falls on February 28 this year. For FPMT students, this day has additional significance as it commemorates the anniversary of the parinirvana of Lama Thubten Yeshe, who co-founded FPMT with Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Lama Yeshe’s heart stopped beating just before dawn on Losar, March 3, 1984. He was forty-nine years old. In 1959, Lama Yeshe fled the Chinese Communists in Tibet, going into exile in India. He survived tremendous hardship living as a refugee monk in Buxa Duar, where Lama Zopa Rinpoche became his heart disciple. In 1967, the two lamas began teaching Western students, leading to the establishment and flourishing of Kopan Monastery in Nepal and the FPMT organization throughout the world.

As part of Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s advice on how to celebrate Losar and the Fifteen Days of Miracles, Rinpoche recommended sharing stories and remembrances about Lama Yeshe. Here Rinpoche discusses the qualities of Lama Yeshe during a teaching given at Kopan Monastery in 2009:

Lama Yeshe was kinder than all the three times’ buddhas. For the tantric meditators, when you bring the wind into the central channel, the in-breath and out-breath are equalized, without one being stronger than the other. When the wind abides in the central channel the belly does not move; it stays calm. There’s no breathing through the nostrils during the absorption when the gross mind stops and only the most subtle mind is actualized.

That meditation on emptiness is like an atomic bomb, the quickest way to cease the defilements and achieve enlightenment. That becomes the direct cause of the dharmakaya. My guess is that when the mind becomes extremely subtle, when the gross mind stops, at that time the heart stops beating, there is no rising or falling of the belly and no breathing through the nose. I’m not sure; that’s just my guess.

Externally, what Lama Yeshe manifested was a heart problem. That’s what people saw; that’s what the doctors diagnosed it as. Lama actually used this heart problem that outside people saw for his meditation session. Lama’s meditation sessions were often Lama lying down and people took that to be him resting or sleeping; that was the view of other people. Actually, for Lama Yeshe that was a meditation session. It was a very high tantric meditation, part of the completion stage practice, the practice of clear light and the illusory body, the direct cause of the dharmakaya and the rupakaya. He did this at night and always after lunch. To other people he was resting or sleeping, but it was actually a meditation session.

Lama didn’t show much sitting in a formal meditation posture with eyes closed and so forth. He did sometimes, later, but it wasn’t normal for him. He was a very high yogi, a very accomplished master, so his way of doing this was kind of secret. That is what was happening internally.

Outside, whoever he was with, he fitted in with them. If he was with children, he fitted in with them; when he was with old people he fitted in with them. Whoever came he fitted in with them, acting in a way that was best for them, in order to make everybody happy. Therefore, everybody saw Lama differently. Some people even saw him as a big businessman. But in reality he was a great meditator who had realizations of emptiness and bodhichitta. He realized emptiness while still in Tibet. He said he realized emptiness while they were debating Madhyamaka philosophy many years ago in Tibet. And I remember something happened while we were in Delhi and Lama said he could never get angry at even one sentient being, he could never renounce even one sentient being. That shows he had the realization of bodhichitta a long time ago.

I pushed Lama to come to Kopan to help with the course. Usually I talked about the eight worldly dharmas and the negative attitude and the lower realms, and I’d spend about two weeks or so on that, then everybody got very depressed, by hearing all the negatives. Then Lama Yeshe came and made them laugh, releasing them from that sadness and depression. This is how we did it.

Excerpted from The Path to Ultimate Happiness, teachings given by Lama Zopa Rinpoche during the forty-second Kopan lamrim course in 2009 at Kopan Monastery, Nepal, lightly edited by Gordon McDougall and Sandra Smith, and published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: lama yeshe, losar

12

Lama Yeshe teaching at Institut Vajra Yogini, Marzens, France, 1982. Photo taken by T.Y. (Thubten Yeshe), courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism is a book from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive consisting of two teachings from Lama Yeshe. The first, The Three Principal Aspects of the Path, was given in France in 1982. The second teaching, Introduction to Tantra, was given at Grizzly Lodge, California, in 1980. Edited by Nicholas Ribush.

During His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s 1982 teachings at Institut Vajra Yogini, France, Lama Yeshe was asked to “baby-sit” the audience for a couple of days when His Holiness manifested illness. The result is this excellent two-part introduction to the path to enlightenment, in which Lama explains renunciation, bodhicitta and the right view of emptiness. Please read an excerpt from Part 2 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path by Lama Yeshe and watch a precious video of Lama giving this teaching at the end of the excerpt.

Good afternoon. Again, unfortunately, I have to come here and talk nonsense to you. However, I heard that His Holiness is feeling much better this afternoon.

This morning I spoke very generally on the subjects of renunciation and bodhicitta. Now, this time, I will talk about the wisdom of shunyata.

From the Buddhist point of view, having renunciation of samsara and loving kindness bodhicitta alone is not enough to cut the root of the ego or the root of the dualistic mind. By meditating on and practicing loving kindness bodhicitta, you can eliminate gross attachment and feelings of craving, but the root of craving desire and attachment are ego and the dualistic mind. Therefore, without understanding shunyata, or non-duality, it is not possible to cut the root of human problems.

It’s like this example: if you have some boiling water and put cold water or ice into it, the boiling water calms down, but you haven’t totally extinguished the water’s potential to boil.

For example, all of us have a certain degree of loving kindness in our relationships, but many times our loving kindness is a mixture—half white, half black. This is very important. Many times we start with a white, loving kindness motivation but then slowly, slowly it gets mixed up with “black magic” love. Our love starts with pure motivation but as time passes, negative minds arise and our love becomes mixed with black love, dark love. It begins at first as white love but then transforms into black magic love.

I want you to understand that this is due to a lack of wisdom—your not having the penetrative wisdom to go beyond your relative projection. You can see that that’s why even religious motivations and religious actions become a mundane trip when you lack penetrative wisdom. That’s why Buddhism does not have a good feeling towards fanatical, or emotional, love. Many Westerners project, “Buddhism has no love.” Actually, love has nothing to do with emotional expression. The emotional expression of love is so gross; so gross—not refined. Buddhism has tremendous concern for, or understanding of, the needs of both the object and the subject, and in this way, loving kindness becomes an antidote to the selfish attitude.

Western religions also place tremendous emphasis on love and compassion but they do not emphasize wisdom. Understanding wisdom is the path to liberation, so you have to gain it.

Now, as far as emotion is concerned, I think for the Western world, emotion is a big thing, for some reason. However, when we react to or relate with the sense world, we should somehow learn to go the middle way.

When I was in Spain with His Holiness, we visited a monastery and met a Christian monk who had vowed to stay in an isolated place. His Holiness asked him a question, something like, “How do you feel when you experience signs of happy or unhappy things coming to you?” The monk said something like, “Happy is not necessarily happy; bad is not necessarily bad; good is not necessarily good.” I was astonished; I was very happy. “In the world, bad is not too bad; good is not too good.” To my small understanding, that was wisdom. We should all learn from that.

Ask yourself whether or not you can do this. Can you experience things the way this monk did or not? For me, this monk’s experience was great. I don’t care whether he’s enlightened or not. All I care is that he had this fantastic experience. It was helpful for his life; I’m sure he was blissful. Anyway, all worldly pleasures and bad experiences are so transitory—knowing their transitory nature, their relative nature, their conventional nature, makes you free.

The person who has some understanding of shunyata will have exactly the same experiences as that priest had. The person sees that bad and good are relative; they exist for only the conditioned mind and are not absolute qualities. The characteristic of ego is to project such fantasy notions onto yourself and others—this is the main root of problems. You then react emotionally and hold as concrete your pleasure and your pain.

You can observe right now how your ego mind interprets yourself, how your self-image is simply a projection of your ego. You can check right now. It’s worth checking. The way you check has nothing to do with the sensory mind, your sense consciousness. Close your eyes and check right now. It’s a simple question—you don’t need to query the past or the future—just ask yourself right now, “How does my mind imagine myself?”

[Meditation]You don’t need to search for the absolute. It’s enough to just ask about your conventional self.

[Meditation]Understanding your conventional mind and the way it projects your own self-image is the key to realizing shunyata. In this way you break down the gross concepts of ego and eradicate the self-pitying image of yourself.

[Meditation]By eliminating the self-pitying imagination of ego, you go beyond fear. All fear and other self-pitying emotions come from holding a self-pitying image of yourself.

[Meditation]You can also see how you feel that yesterday’s self-pitying image of yourself still exists today. It’s wrong.

[Meditation]Thinking, “I’m a very bad person today because I was angry yesterday, I was angry last year,” is also wrong, because you are still holding today an angry, self-pitying image from the past. You are not angry today. If that logic were correct, then Shakyamuni Buddha would also be bad, because when he was on earth, he had a hundred wives but was still dissatisfied!

Our ego holds a permanent concept of our ordinary self all the time—this year, last year, the year before: “I’m a bad person; me, me, me, me, me, me.” From the Buddhist point of view, that’s wrong. If you hold that kind of concept throughout your lifetime—you become a bad person because you interpret yourself as a bad person.

Therefore, your ego’s interpretation is unreasonable. It has nothing whatsoever to do with reality. And because your ego holds onto such a self-existent I, attachment begins.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read Part 2 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path in its entirety.

We are so pleased to share a video of Lama Yeshe offering this teaching:

This talk is included in Lama Yeshe’s book The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism. You can also view the talks on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive YouTube channel, listen to the audio book, or read the book online.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: essence of tibetan buddhism, lama yeshe

15

Lama Yeshe teaching at Institut Vajra Yogini, Marzens, France, 1982. Photo taken by T.Y. (Thubten Yeshe), courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism is a book from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive consisting of two teachings from Lama Yeshe. The first, The Three Principal Aspects of the Path, was given in France in 1982. The second teaching, Introduction to Tantra, was given at Grizzly Lodge, California, in 1980. Edited by Nicholas Ribush.

During His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s 1982 teachings at Institut Vajra Yogini, France, Lama Yeshe was asked to “baby-sit” the audience for a couple of days when His Holiness manifested illness. The result is this excellent two-part introduction to the path to enlightenment, in which Lama explains renunciation, bodhicitta and the right view of emptiness. Please read an excerpt from Part 1 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path by Lama Yeshe and watch a precious video of Lama giving this teaching at the end of the excerpt.

First of all, all of us consider that we would like to be free from ego mind and the bondage of samsara. But what binds us to samsara and makes us unhappy is not having renunciation. Now, what is renunciation? What makes us renounced?

The reason we are unhappy is because we have extreme craving for sense objects, samsaric objects, and we grasp at them. We are seeking to solve our problems but we are not seeking in the right place. The right place is our own ego grasping; we have to loosen that tightness, that’s all.

According to the Buddhist point of view, monks and nuns are supposed to hold renunciation vows. The meaning of monks and nuns renouncing the world is that they have less craving for and grasping at sense objects. But you cannot say that they have already given up samsara, because monks and nuns still have stomachs! The thing is that the English word “renounce” is linguistically tricky. You can say that monks and nuns renounce their stomachs, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they actually throw their stomachs away.

So, I want you to understand that renouncing sensory pleasure doesn’t mean throwing nice things away. Even if you do, it doesn’t mean you have renounced them. Renunciation is a totally inner experience. Renunciation of samsara does not mean you throw samsara away because your body and your nose are samsara. How can you throw your nose away? Your mind and body are samsara—well, at least mine are. So I cannot throw them away. Therefore, renunciation means less craving; it means being more reasonable instead of putting too much psychological pressure on yourself and acting crazy.

The important point for us to know, then, is that we should have less grasping at sense pleasures, because most of the time our grasping at and craving desire for worldly pleasure does not give us satisfaction. That is the main point. It leads to more dissatisfaction and to psychologically crazier reactions. That is the main point.

If you have the wisdom and method to handle objects of the five senses perfectly such that they do not bring negative reactions, it’s all right for you to touch them. And, as human beings, we should be capable of judging for ourselves how far we can go into the experience of sense pleasure without getting mixed up and confused. We should judge for ourselves; it is completely up to individual experience. It’s like French wine—some people cannot take it at all. Even though they would like to, the constitution of their nervous system doesn’t allow it. But other people can take a little; others can take a bit more; some can take a lot.

So, I want you to understand why Buddhist scriptures completely forbid monks and nuns from drinking wine. It is not because wine is bad; grapes are bad. Grapes and vines are beautiful; the color of red wine is fantastic. But because we are ordinary beginners on the path to liberation, we can easily get caught up in negative energy. That’s the reason. It is not that wine itself is bad. This is a good example for renunciation.

Who was the great Indian saint who drank wine? Do you remember that story? I don’t recall who it was, but this saint went into a bar and drank and drank until the bartender finally asked him, “How are you going to pay?” The saint replied, “I’ll pay when the sun sets.” But the sun didn’t set and the saint just kept on drinking. The bartender wanted his money but somehow he controlled the sunset. These kinds of higher realization—we can call them miraculous or esoteric realizations—are beyond the comprehension of ordinary people like us, but this saint was able to control the sun and drank perhaps thirty gallons of wine. And he didn’t even have to make pipi!

Now, my point is that renunciation of samsara is not only the business of monks and nuns. Whoever is seeking liberation or enlightenment needs renunciation of samsara. If you check your own life, your own daily experiences, you will see that you are caught up in small pleasures—we [Buddhists] consider such grasping to be a tremendous hang-up and not of much value. However, the Western way of thinking—”I should have the best; the biggest”—is similar to our Buddhist attitude that we should have the best, most lasting, perfect pleasure rather than spending our lives fighting for the pleasure of a glass of wine.

Therefore, the grasping attitude and useless actions have to be abandoned and things that make your life meaningful and liberated have to be actualized.

But I don’t want you to understand only the philosophical point of view. We are capable of examining our own minds and comprehending what kind of mind brings everyday problems and is not worthwhile, both objectively and subjectively. This is the way that meditation allows us to correct our attitudes and actions. Don’t think, “My attitudes and actions come from my previous karma, therefore I can’t do anything.” That’s a misunderstanding of karma. Don’t think, “I am powerless.” Human beings do have power. We have the power to change our lifestyles, change our attitudes, change our habits. We can call that capacity Buddha potential, God potential or whatever you want to call it. That’s why Buddhism is simple. It is a universal teaching that can be understood by all people, religious or non-religious.

The opposite of renunciation of samsara—to put what I’m saying another way—is the extreme mind that we have most of the time: the grasping, craving mind that gives us an overestimated projection of objects, which has nothing to with the reality of those objects.

However, I want you to understand that Buddhism is not saying that objects have no beauty whatsoever. They do have beauty—a flower has a certain beauty, but that beauty is only conventional, or relative. The craving mind, however, projects onto an object something that is beyond the relative level, which has nothing to do with that object, that hypnotizes us. That mind is hallucinating, deluded and holding the wrong entity.

Without intensive observation or introspective wisdom, we cannot discover this. For that reason, Buddhist meditation includes checking. We call checking in this way analytical meditation. It involves logic; it involves philosophy. So Buddhist philosophy and psychology help us see things better. Therefore, analytical meditation is a scientific way of analyzing our own experience.

Finally, I also want you to understand that monks and nuns may not be renounced at all. It’s true, isn’t it? In Buddhism, we talk about superficial structure and universal structure. So when we say monks and nuns renounce, it means we’re trying, that’s all. Westerners sometimes think monks and nuns are holy. We’re not holy; we’re just trying. That’s reasonable. Don’t overestimate again, on that. Lay people, monks and nuns—we’re all members of the Buddhist community. We should understand each other well and then let go; leave things as they are. It’s unhealthy to have overestimated expectations of each other.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read Part 1 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path in its entirety.

We are so pleased to share a video of Lama Yeshe offering this teaching:

This talk is included in Lama Yeshe’s bookThe Essence of Tibetan Buddhism. You can also view the talks on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive YouTube channel, listen to the audio book, or read the book online.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

24

Lama Yeshe at Kopan Monastery, 1971. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Around Christmas time between 1971 and 1975, Lama Yeshe gave several talks related to Christmas to the Western students at Kopan Monastery, Nepal, in case some of them were missing their families and being at home at that festive time of year. These talks, and another given on Christmas Day, 1982, at Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa during Lama’s teachings on the Six Yogas of Naropa, have been collected into the book Silent Mind Holy Mind. So many years later, we share these precious teachings this time of year with students new and old who can benefit from Lama’s timeless advice. We also share our best wishes to all for the observation of Lama Tsongkhapa Day, which falls this year on December 25, Christmas Day.

Below we share an excerpt from Chapter 4 of Silent Mind, Holy Mind, which is from a talk given by Lama Yeshe in 1982 at Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa in Pomaia, Italy. We are also so pleased to share a video of this teaching:

Christmas, 1982

By Lama Yeshe

Somehow, we’re still alive and aware enough to remember how long it is since Jesus was born. It was one thousand, nine hundred and eighty-two years ago, right? And I myself am fortunate enough to have been born in the Shangri-la of Tibet, to have come into contact with the world of Western dakas and dakinis, and to have this chance to acknowledge the history of the holy guru, Jesus.

I’ve found that having a little understanding of Jesus’s life helps me develop my own path, but it’s not easy to fully understand the profound events in Jesus’s life. It’s quite difficult. Of course, the superficial events of his life are fairly easy to understand, but there’s not enough room in our mind to comprehend his high bodhisattva actions. Even when Lord Jesus and Lord Buddha were here on earth it was very difficult for ordinary people to understand who they really were. At that time, very few people understood.

Today I was looking at the Bible, at the Gospel of John in particular, and he was talking about the miracles Jesus performed and how few people understood the profundity of his liberated mind that allowed him to perform those miracles.

Anyway, whenever I’m at a meditation course such as this at Christmas time, I like to talk about this kind of thing. But you need to understand that when I do, I’m not trying to be diplomatic. I don’t need to negotiate my relationship with you in that way. It’s just that from the bottom of my heart, I sincerely feel and believe that simply to remember Jesus’s life is an incredible opportunity.

In a way, of course, it doesn’t matter where people come from— East or West—or what color they are, those who eliminate their self-cherishing thought and give their life for others are exceptional human beings. For that reason, I’m happy just to bring Jesus to mind and reflect on what he did.

Also, to some extent I’m responsible for my Western students’ psychological wellbeing, so if we’re going to bring Buddhism to the West, we need to do it in a healthy way rather than introduce it as some exotic new trip. We don’t need new trips—we need to do something constructive, something worthwhile. Anything truly worthwhile does not diminish any light; it only enhances it.

And with respect to psychological health, we’re part of the environment and the environment is part of us. Therefore, those of us who were born in the West should not reject the Christian environment into which we were born. We should consider ourselves lucky to have been born into a Christian society and to have the wisdom to understand what that means for our mind. Such understanding is very useful if we’re to remain healthy. Especially these days, when there’s dangerous revolutionary technology everywhere and the world is overwhelmed with fighting and war, we really need to actively remember the lives of our unselfish historical predecessors.

So, John was explaining how God sent Jesus to us as a witness to the truth, but most unfortunately, some ignorant people failed to recognize who he was or understand what he was teaching and killed him. In my opinion, the Buddhist point of view is that Jesus was a bodhisattva, not only in the sense that he had realized bodhicitta and overcome selfishness, but in the sense that, as a performer of miracles, he was a saint, like Tilopa and Naropa or, to name a living example, His Holiness Zong Rinpoche—somebody completely free of superstition who sometimes instinctively does strange things that the rest of us don’t understand.

For example, John says that one day Jesus was near the water when a woman came by to fill her pot. Jesus said to her, “How can you satisfy your thirst with water? It’s water that makes you thirsty in the first place.” He told her that since it’s water that makes her thirsty, how can water be the solution to her thirst. It’s some kind of reverse thinking. Who can understand that? It sounds crazy, doesn’t it?

What he meant was that only spiritual water can truly slake your thirst. So you can see, the actual meaning is somehow beyond words. The woman’s taking water; he says, “Why are you doing that? It’s not going to solve your problem of being thirsty.” It’s crazy talk. Nowadays we’d probably hit somebody who spoke to us like that. But luckily, back then Jesus didn’t get beaten up for talking in that way.

John also said that since Jesus was born from God, his disciples were also derived from God’s energy. That’s similar to what the Buddhist teachings say when they explain that all shravakas and pratyekabuddhas are born from Shakyamuni Buddha. The sense here is that such followers are born from the teacher’s wisdom truth speech. Through internalizing that, they discover the truth for themselves and become such realized beings.

Philosophically, of course, we can say that Buddhism doesn’t accept that God is the source of all human beings and other things. But from another point of view, we can say that Buddhism doesn’t contradict that statement either. For example, where does the human realm come from? The Buddha said that the human realm is caused by good karma. That’s true. If the upper realms do not come from good karma, then where do they come from? Then, from the Buddhist point of view, all good karma comes from the Buddha…or, you can say, God. Therefore, the human realm comes from God, from Buddha. Because of the Buddha’s holy speech, sentient beings create good karma. I want you to be clean clear about this.

Still, philosophically you can argue this point one way or the other. It depends on how you interpret it. You can interpret the statement negatively or positively. Actually, you can do anything with philosophy.

Now, concerning God, what is the different between Buddha and God? Today, I’m going to say that according to Buddhism and

Christianity, the qualities of the Buddha and the qualities of God are the same. People always worry about creation. “God is the creator of everything; Buddha is the creator of everything.” Does that mean the Buddha created negativity? Well, the Buddha said that ultimately, there’s no positive, there’s no negative.

Tibetans address this issue with the example of a river. When you’re standing on one bank of the river you call the opposite bank “the other side.” When you’re on that bank you call this one “the other side.” There’s this side and that side, that side and this side. It’s interdependent. Without each other, this side and that side wouldn’t exist. In the same way, if positive doesn’t exist, negative

can’t exist either. In other words, negative comes from positive, positive comes from negative.

Then maybe you’re going to argue, “Well, if God is the creator, if God is the cause of everything, such as organic things like plants, then how can God be permanent?” People say God is permanent—then how can something that’s permanent produce

something impermanent, like a plant? The principal cause of an impermanent phenomenon has to also be impermanent.

That sort of argument comes from Buddhists, so I’m going to debate with them: “Then how can you say shravakas and pratyekabuddhas are born from Buddha? Buddha is permanent.” The answer to that is that such statements are not meant to be taken literally. In response to that, I’m going to say, “Well, God can be the same as Buddha, in the sense of a personal being. God can be a person in the same way Shakyamuni Buddha was.” It’s not as if a permanent God is sitting up there somewhere. God can be something organic, a personal being with whom you can personally relate.

I tell you, philosophers always try to make everything very special. “God. Buddha. God is this; Buddha is that.” They put God and Buddha up on some kind of untouchable pedestal, so ordinary people can’t relate to them. They make it impossible to understand the nature of God, the nature of Buddha. That’s stupid. They just create more obstacles for people.

Then human beings, with their limited minds, try to put cream on God, chocolate on God, like with a knife. They put their own garbage on God. That’s all wrong; definitely wrong. I truly believe that sometimes philosophy can become an obstacle to people really understanding the nature of God or Buddha. Maybe I’m a revolutionary, but I reject many of the philosophical positions on these matters.

However, personifying God or Buddha doesn’t contradict their omnipresent nature. We can talk about the personal qualities of Heruka, for example, but at the same time, he is universal and omnipresent. We need to understand that.

Excerpted from Silent Mind, Holy Mind, Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive, 2024, edited by Jon Landaw and Nicholas Ribush.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: silent mind holy mind

5

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Follow Your Path Without Attachment

Lama Yeshe teaching at Les Bayards, Switzerland, 1975. Photo by Barbara Vautier, courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind one of the most beloved free books from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. The six teachings contained in this volume come from Lama Yeshe’s 1975 visit to Australia. They are all filled with love, insight, wisdom and compassion, and accessible question-and-answer sessions.

Please enjoy Chapter 6 of The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “Follow Your Path Without Attachment” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at Chinese Buddhist Society, Sydney, AUS, April 24, 1975. Edited by Nicholas Ribush:

Those who practice meditation or religion should not cling with attachment to any idea.

Fixed ideas are not external phenomena. Our minds often grasp at things that sound good, but this can be extremely dangerous. We too easily accept things we hear as good: “Oh, meditation is very good.” Of course, meditation is good if you understand what it is and practice it correctly; you can definitely find answers to life’s questions. What I’m saying is that whatever you do in the realm of philosophy, doctrine or religion, don’t cling to the ideas; don’t be attached to your path.

Again, I’m not talking about external objects; I’m talking about inner, psychological phenomena. I’m talking about developing a healthy mind, developing what Buddhism calls indestructible understanding-wisdom.

Some people enjoy their meditation and the satisfaction it brings but at the same time cling strongly to the intellectual idea of it: “Oh, meditation is so perfect for me. It’s the best thing in the world. I’m getting results. I’m so happy!” But how do they react if somebody puts their practice down? If they don’t get upset, that’s fantastic. It shows that they are doing their religious or meditation practice properly.

Similarly, you might have tremendous devotion to God or Buddha or something based on deep understanding and great experience and be one hundred percent sure of what you’re doing, but if you have even slight attachment to your ideas, if someone says, “You’re devoted to Buddha? Buddha’s a pig!” or “You believe in God? God’s worse than a dog!” you’re going to completely freak out. Words can’t make Buddha a pig or God a dog, but still, your attachment, your idealistic mind totally freaks: “Oh, I’m so hurt! How dare you say things like that?”

No matter what anybody says—Buddha is good, Buddha is bad—the absolutely indestructible characteristic nature of the Buddha remains untouched. Nobody can enhance or decrease its value. It’s exactly the same when people tell you you’re good or bad; irrespective of what they say, you remain the same. Others’ words can’t change your reality. Therefore, why do you go up and down when people praise or criticize you? It’s because of your attachment; your clinging mind; your fixed ideas. Make sure you’re clear about this.