- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

You don’t need to obsess over the attainment of future realizations. As long as you act in the present with as much understanding as you possibly can, you’ll realize everlasting peace in no time at all.

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

Man’s Work – Part I

by Mick Brown, photographs by Peter Bialobrzeski

Reproduced with permission from Telegraph Magazine, London – 27 April 1996

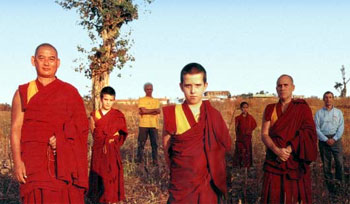

From the age of 19 months, when he was identified as the reincarnation of a Tibetan lama, Osel Hita Tores has lived like no other child. Transported from a Spanish village to a Tibetan Buddhist monastery in India, he is now, at age 11, the subject of what is described as ‘potentially the most exciting experiment in education, done anywhere, at any time.’

THROUGHOUT THE LONG AND exhausting drive from the city of Bangalore to Sera monastery, I had been considering the protocol involved in meeting Osel Hita Torres.

How does one behave towards an 11-year-old Spanish boy who is said to be the reincarnation of a Tibetan lama – a boy who already is the spiritual figurehead for tens of thousands of Buddhists around the world? Do you bow? Shake hands? Bring toys? From the age of two, Lama Osel has been accustomed to visitors prostrating themselves before him and offering him the ritualistic white silk scarf – the kata – which he in turn drapes around their necks. I have no kata, and I am unsure about prostrating myself before an 11-year-old.

In the event my fears are groundless. Lama Osel greets me at the door of his house, an unusually tall and sturdy boy for his age dressed in maroon robes and a pair of flip-flops, his expression of seriousness momentarily illuminated by a shy smile. Sensing my hesitancy, he holds out his hand and shakes mine firmly. He offers tea, which is brought by a Tibetan attendant, and which we drink on the verandah.

As a reincarnate lama, the young boy occupies a privileged position in monastery life. His home is a large, airy bungalow, set in its own grounds. A housekeeper tends the flowerbeds, and a blind, pet deer contentedly grazes the lawn.

The young lama offers a tour of his house; his bedroom, decorated with Tibetan religious tapestries, and a large shrine, with effigies of saints and a golden Buddha in a glass case; his playroom, where there is another shrine, more hangings and almost shockingly incongruous – the biggest Lego set I have ever seen.

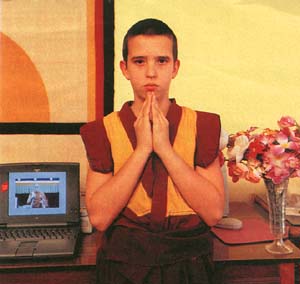

In the lama’s classroom is an old-fashioned school desk and a table-top science laboratory with scales, a microscope and a rack of test-tubes. The shelves are crammed with school text-books and improving novels: Watership Down, Kidnapped, The Hobbit. Sitting on an adjacent desk is his laptop computer (he is linked up to the Internet) and a stack of software disks.

‘Do you play SimCity?’ he asks enthusiastically. ‘Sim-Tower, Sim-Farm, or I’ve got Doom2…’ Lama Osel’s lessons begin at six in the morning with prayers and the memorisation of Buddhist teachings; they end at nine at night, when his Tibetan teacher carefully wraps the loose-leaf religious texts in their binding of gold cloth. In the hours between there is English, Spanish, history, science, geography, mathematics, instruction in Buddhist philosophy and dialectics.

But now it is dinner time. The young lama switches off his computer and comes to the table. We are seven: Lama Osel, his father Paco and his eight-year-old brother Kunkyen who, like the lama, is dressed in the maroon robes of a monk. There is the lama’s Tibetan attendant, Pemba; his American tutor, George Churinoff; and Peter Kedge, from the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition – an English Buddhist and businessman who is in charge of Lama Osel’s education, and who is visiting from his base in Hong Kong to check on his young charge’s progress.

The boy leads grace, in Tibetan, and there is a moment’s pause as all around the table wait for him to begin to eat. The conversation turns to philosophy. George Churinoff, a 50-year-old American Buddhist monk and MIT physics graduate, expounds on the nature of reality. What do we mean when we talk of a tree? A table? A body? Do these things have an absolute reality? No, they are merely names for a composite of parts, each of which is a composite of smaller parts, breaking down to a degree where the parts cannot be measured; they are simply energy. The Ii-year-old boy toys with his food, listening intently, then picks up the thread of the argument. ‘So a cup is impermanent, the body is impermanent. Only emptiness is permanent…’ He pauses, and turns to me. ‘You’re like me,’ he says, ‘you eat very slowly,’ and laughs.

THERE IS A BUDDHIST SAYING ABOUT reincarnation. If you wish to know of your past life, consider your present circumstances; if you wish to know of your future life, consider your present actions. The present circumstances of Osel Hita Torres were shaped some 14 months before he was born, on the day that a 49-year-old Tibetan Buddhist lama named Thubten Yeshe died from a heart complaint in a Californian hospital ward.

His future can roughly be described as follows: by the age of 19 he will have been tutored in both the centuries-old teachings of Tibetan Buddhism and the contemporary teachings of the technological West; he will be engaged in a degree course in, say, nuclear physics, or perhaps psychology; at the same time he will be travelling the world, lecturing and running an organisation that embraces monasteries, retreats, hospices and homes for the destitute.

‘I think what we are engaged in,’ says Peter Kedge, ‘is potentially the most exciting experiment in education, probably done anywhere, at any time.’ This, I say to Kedge, is a daunting prospect for an Ii- year-old boy. He nods. ‘Yes, Lama is aware he has a big load to carry.’ And is he happy with that? ‘I’ve honestly never heard him express any hesitation. It was Lama Yeshe’s work, and Lama Osel has always been quite clear that his role is to carry that on.’

ACCORDING TO TIBETAN BUDDHIST teaching, while reincarnation is inevitable for everyone, there are certain beings who have so trained their minds through intensive study and meditation that they can influence the conditions of their next birth. These tulkus, as they are known, are bound by their vow to return to lead others to enlightenment. The Dalai Lama, whose lineage can be traced through 14 successive rebirths, is the best known. But within Tibetan Buddhism at large there are many such tulkus. Sera monastery alone accommodates some 25 of them.

Traditionally, this recognition was confined to Tibet, but the diaspora that followed the popular uprising against the Chinese in 1959, when the Dalai Lama led thousands of Tibetans into exile, brought countless lamas and teachers to the West, and in recent years Western reincarnates have been identified in Canada, France, Spain and America. Lama Osel is the best known of these, and his story was the inspiration for Bernardo Bertolucci’s film about a Western reincarnate, Little Buddha.

Lama Yeshe himself had been identified at an early age as the reincarnation of a Tibetan abbess. He spent his early years in a monastery in Tibet, fleeing the country in 1959 at the same time as the Dalai Lama. He eventually settled in Kathmandu, where he started to gather Western students around him.

Peter Kedge was one of the first. Now 48, Kedge grew up in a devout Christian family in Birmingham. He studied engineering at university, but in the early Seventies set off with a group of friends in a Land Rover on the hippie trail across Asia, eventually arriving in Kathmandu. Meeting Lama Yeshe, he says, was ‘a revelation. For the first time in my life I was receiving crisp, clear, scientific answers to all the questions I’d always been asking – why we are born, why we die, why some people have good lives and others bad.

Kedge became Lama Yeshe’s attendant for four years, organising lecture tours and helping to establish the Lama’s organisation, the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition. It was Lama Yeshe’s particular skill, he says, to extract the essence of Buddhist philosophy and psychology ‘what makes you happy or unhappy, the purpose of life, and how to solve life’s everyday problems’ from its Tibetan packaging and make it lucid and understandable to Western students. The FPMT now has some 70 centres around the world.

The young lama has a bearing, an awareness of others’ moods, and a mindfulness of their well-being–’Are you OK?’ he will ask–which would be uncommon in an adult, let alone an 11-year-old.

When Lama Yeshe died, the responsibility for finding his reincarnation fell to his student and closest friend, Lama Zopa. In accordance with tradition, he consulted several oracles mediums who are in touch with the guiding and protecting spirits of Tibetan Buddhism. These indicated that in his next life Lama Yeshe would choose a Western reincarnation to continue his work of teaching.

Zopa studied his dreams. In one, Lama Yeshe appeared, telling his old friend that he was about to take human form. Much later, Zopa dreamed of a Western baby, crawling across the floor towards him. Convinced that Lama Yeshe’s reincarnation was now in the world, Zopa began his search in earnest, visiting the centres and monasteries that Lama Yeshe had founded in his lifetime. At length he came to the small village of Bubión, high in the Alpujarra mountains near Granada, where Paco Hita and his girlfriend Maria Torres, both former students of Lama Yeshe, had helped round a Buddhist retreat. Lama Yeshe had visited the retreat a year before he died and thanked Paco and Maria for their work. ‘Even if I die,’ he told them, ‘I will never forget you. We have much business, much karma business between us.

Six months before Zopa’s arrival in the village Paco and Maria had had their fifth child, Osel: Lama Zopa immediately recognised him as the baby in his dreams. He asked Maria, when exactly was the baby conceived? It was the night of Zopa’s first dream. He said nothing then to the parents about reincarnation, only that Osel was a very special child; that he should be kept in an unpolluted atmosphere, and that nobody should be allowed to ruffle his head.

Even when Maria had been pregnant with Osel, says Paco, something had seemed slightly different. Paco’s work as a builder had always been irregular and life for the large family was difficult, yet during the pregnancy Maria seemed unusually relaxed, and suddenly there was more work, more money. Paco was able to build extra rooms on his house, with a nursery for the new child.

Paco practised his daily meditation in the baby’s room. ‘I don’t know why, he says, `but sometimes I had these incredible feelings. I would open my eyes and many times see Lama Osel looking at me with very wide eyes, and then laughing. When I was first with Lama Yeshe, we didn’t speak, but we had incredible communication. And it was the same with this baby.

At length, the Dalai Lama announced that he had made his own divinations. confirming the recognition. Finally came the public affirmation, when Osel was presented with a selection of hand-bells and prayer- beads and unerringly selected those which had belonged to his predecessor.

Osel Hita Torres was just 19 months old when he was proclaimed as ‘the absolute and irrefutable’ reincarnation of Lama Yeshe. Paco says he did not know what to think.’I needed time to meditate, to think about this. I needed to feel it in my heart.’

And now?

‘Now, I feel it.

Why, I ask Paco, does he think his family was chosen? ‘Not because I am a good person, no. 1 think because we are a big family, we have many children and are less attached to them. That way it is easier for Osel to follow the way to help many thousands of sentient beings.

‘Lama Yeshe’s motivation was always incredible. When I first met him in 1977 I didn’t understand Buddhism, nothing – but his compassion, his understanding reached me. And now we have Lama Osel who speaks English, Spanish, Tibetan, he understands computer. It is as if he has made this incredible body to help the world.’

At his enthronement ceremony at Dharmsala, in northern India, the two-year-old lama, dressed in ceremonial robes and the curved, yellow pandit’s hat, accepted ritual offerings, grinned, yelled, chewed sweets and played with a toy car. At the end of the ceremony, he wriggled off the platform and ran to his father, Paco, who carried him out of the temple, his destiny changed forever.

LAMA OSEL SUGGESTS THAT HE, THE photographer and I should play SimCity on his computer – a game that involves planning and building a city from the power supply up. As much as this is entertainment, it is also an ad hoc lesson in financial and social management.

‘OK,’ Lama says. ‘Before we build anything, we all have to agree. If two say yes and one says no, we do it. If two say no, we don’t.’ Such diplomacy is not normal behaviour in an Ii-year-old.

Lama allocates an area of forestland ‘for the animals to live in – do you agree?’ He sensibly installs hospitals, schools, a police station. ‘Perhaps we should raise taxes,’ I suggest. ‘The people don’t like it,’ he says. ‘We must keep the people happy.’

UNTIL NOW, PETER KEDGE ADMITS, Lama Osel’s upbringing and education has been largely a case of’ trial and error’. In Tibet, a young reincarnate would be given up to the monastery at an early age; his parents would welcome it as an honour. But what is appropriate for a Tibetan tulku is not necessarily appropriate for a Western child; trying to strike a balance between the requirements of tradition and the expectations of a normal family life has not been easy.

From an early age Lama Osel led a peripatetic life. In order for students of Lama Yeshe to ‘reacquaint’ themselves with their reincarnated teacher, he travelled to monasteries and centres in Nepal, America, Australia and Europe, usually in the company of one or other of his parents.

As Buddhists and students of Lama Yeshe, Paco and Maria had always acknowledged that, at some point, it would be necessary for their son to enter a monastery in order to continue his education. In 1991, at the age of seven, the young lama left his parents in Spain and took up residency in Sera, some 50 miles from Mysore.’

Man’s Work – Part II

by Mick Brown, photographs by Peter Bialobrzeski

Reproduced with permission from Telegraph Magazine, London – 27 April 1996

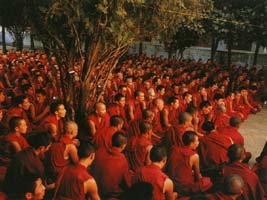

Sera is one of the three great ‘monastic universities’ of Tibetan Buddhism that have been relocated in India since 1959. Home to some 3,000 monks and growing, Sera is, in fact, a small town, its temples surrounded by a tangle of houses and accommodation blocks, narrow unpaved streets and pathways. It is a place where the days are measured by the incessant sound of chanting and recitations; the chatter of maroon-robed monks, many of them children, scurrying along the dusty paths to their classes, and the mournful sound of the Tibetan ‘longhorn’, echoing over the corrugated rooftops. It is as far from Spain as could be imagined.

A Western monk served as Lama Osel’s attendant, and a classics scholar from Yale and her husband were employed as private tutors. But after less than a year, things began to go wrong. The young boy complained of missing his family and began to kick against the strictures of monastery life. His mother travelled to India and took her son back to Spain.

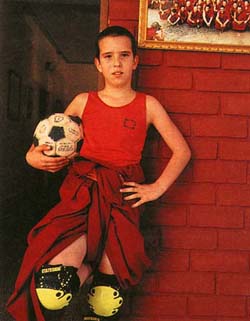

Back in his village the boy began to eclipse the lama. It was, says Paco, ‘a bad time.’ Lama became an ordinary boy in the village. There was no studying; he speak bad words; he is fighting and playing the pinball machine all night with the other boys.’ Things were complicated still further by the fact that Paco and Maria’s relationship had now ended; the young lama was caught in the middle of an awkward separation.

Paco was working in London, refurbishing the Kensington house where J.M. Barrie wrote Peter Pan. Lama came to see me for three weeks and he was a completely changed boy, undisciplined, unbelievable.’

A meeting was called between Paco, Maria and the heads of the FPMT, in which the young boy declared that he would return to Sera, on the condition that Paco and his younger brother, Kunkyen, go with him. But the family difficulties were not altogether resolved. Last year his mother, Maria, claimed to a newspaper reporter that her son’s monastic education was ‘making him a Tibetan’ and said that she wanted him to spend more time with her family in Spain. The young lama subsequently visited Spain for three weeks at the end of last year, and a timetable has now been devised which allows for regular visits in future.

Paco is in no doubt that Sera is the best place for his son. ‘He is happy here, and that is ‘the most important thing, because when he’s happy his mind is open and he wants to learn. When he’s not happy, learning is so difficult. He has good health, good teachers, a good environment. These are the best conditions for him to become a very good person.’ It is, by any standards, an unusual household. Responsibility for the young Lama’s discipline is divided between his father and a Tibetan attendant, Pemba Tenzin Sherpa. There is a cook and a housekeeper–both male.

It is the custom for tulkus to be kept apart from general monastic activities until they are 13 or 14. For Lama Osel there are occasional excursions to a nearby nature reserve, to Mysore and, sometimes, to the seaside. Friends come to play. But for the most part, his life is spent within the walls of his garden compound.

A timetable taped to the door of his classroom measures a 15-hour working day six days a week. His lessons in English, science, history, mathematics and geography are taken from an education package provided by an English organisation and based on the National Curriculum. His father, Paco, teaches Spanish. Lessons in Tibetan language are given by Pemba, and in Tibetan script, memorisations and philosophy by a senior Sera geshe (the Tibetan equivalent of a Doctor of Divinity), Gendon Chombal, known simply as ‘Geshe-la’.

It is a demanding regime; yet if you were to ask if the young boy seems happy, I would have to say he does. In six days I see no sign of distraction, tantrums or fractiousness. I arrive each morning for breakfast, to the sound of the young lama chanting prayers in his room. I leave after supper to the same sound, like a thread which runs through each day, connecting it to the next, and the next.’ln a world filled with suffering, please grant me the blessings to help all sentient beings. In a world filled with suffering, please grant me the blessings to help all sentient beings. In a world filled with suffering…

ANOTHER REINCARNATE LAMA, a sturdy 13-year-old Tibetan boy, has come to play. ‘They are old friends,’ Peter Kedge explains. He means very old friends, for in his previous incarnation, the Tibetan boy was Lama Yeshe’s teacher. A noisy and energetic game of football ensues in the corridor outside. Pemba, Lama’s Tibetan attendant, looks on disapprovingly–it is not seemly for lamas to play football–but says nothing.

At supper that night we talk about food. ‘In Spain,’ says Lama, ‘I went to McDonald’s and the people were eating all this food and I couldn’t understand it.’ He wrinkles his nose in exaggerated disgust. ‘It’s so plastic. So horrible.’ In a curious way, this is one of the most remarkable things I hear Lama Osel say. Is there another Ii-year-old in the world who doesn’t like McDonald’s?

IN THE DAYS I SPEND WITH LAMA OSEL I become aware that he is, in a sense, watching me watching him. And it occurs to me that he is someone who has grown up under perpetual scrutiny, perpetually aware of others looking to him for signs of affirmation or progress.

According to Buddhist teaching, after death the consciousness remains, carrying traces, or imprints, shaped by the thoughts and actions of the previous life into the next one. This could be one explanation, Peter Kedge believes, for child prodigies who demonstrate an unusual facility for, say, mathematics or playing the piano at a very early age. Our culture does not accommodate the idea that these are ‘imprints’ from a previous life. But in the case of a tulku, who has ‘chosen’ his reincarnation, the imprints of his previous life are thought to be unusually developed, and are carefully looked for.

These imprints are said to be more recognisable in the early years: there are countless stories of young reincarnates crawling from their houses towards the monastery where they used to live, or commanding their playmates to make prostrations in front of them. As time passes, the imprints fade. From an early age, Lama Osel is said to have shown signs of unusual behaviour, enacting ritualistic gestures quite spontaneously, and showing signs of ‘recognising’ former students and, in one case, the reincarnation of an old friend.

Lama Yeshe liked gardening; Lama Osel, it is said, showed an early enthusiasm for it, too. Lama Yeshe was often to be found in the kitchen, lifting the lids on pots, tasting the food, checking on everybody’s well-being. The young Lama Osel displayed the same traits.

I read that Lama Yeshe had a habit of rubbing his head for no apparent reason. At the dinner-table one night, I notice with a start that Lama Osel is doing exactly the same thing. We are talking about the Lama’s studies. He has been reading about the Aztecs. ‘It’s so interesting,’ he says. ‘I read about it and immediately go right into it.’ Why do you like them so much? I ask. Lama gives it some thought. ‘It reminds me of Tibet.’ He has never been to Tibet, although Lama Yeshe, of course, was born there.

‘Lama Osel is not Lama Yeshe, he is himself,’ says Paco. ‘In some ways, there is no similarity. But I do feel that there is incredible compassion and love there, and a very clear, lucid mind. I am surprised sometimes. He’ll ask me a question and then challenge my answer; he has an incredible ability to show me aspects of myself. And his relationships with others are interesting. I’ve noticed that when people around him are proud, his attitude to them is very hard; he is not impressed. But when people are humble, he responds with great sympathy.

I had noticed this. The young lama has a bearing, an awareness of others’ moods, and a mindfulness of their well-being–’Are you OK?’ he will ask at odd moments–which would be uncommon in an adult, let alone an 11-year-old. Watching him at his studies, conversing at the dinner-table and playing with his Lego, I am torn between wondering if he is an 11-year-old pretending to be a grown-up, or a grown-up pretending to be an 11-year-old.

Reincarnation adds a further imponderable to the timeless question of nature versus nurture. To the outsider, it is impossible to tell how much Lama Osel’s obvious intelligence and composure, his readiness to volunteer opinions, is ‘karmic imprint’ and how much the consequence of being brought up in an environment which is, by any standards, scholastic and serious-minded, There is 170 television, no videos, no pop music. One senses that everything that is said to him–everything he is exposed to–is carefully weighed and considered.

When I raise the matter of signs and wonders with the young lama’s Tibetan teacher, Geshe-la, his pensive expression suggests that these things are not easily explained.

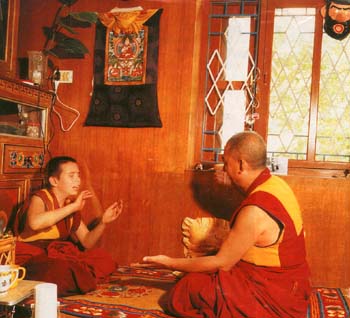

‘For myself, I have no personal divination that Lama Osel is a reincarnation, but there are things that I see. Sometimes when I explain the teachings he grasps them very quickly and actually elaborates from his own side, which is remarkable for one so young. For me, that shows there is some imprint.’ Geshe-la is an estimable figure, who has spent 45 years in monastic studies and is now responsible for the tuition of 1,000 monks in Sera. He arrives each s afternoon to take the young lama’s class in Tibetan : language and dialectics. The 11-year-old Spanish boy and his 55-year-old Tibetan teacher face each other, cross- legged, on the floor of Lama’s room, overlooked by a portrait of the Dalai Lama and a mask of the cartoon character Captain Haddock. They enact a ritual with dorje and bell, make offerings to the Buddha and the deities, then begin.

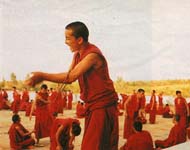

The lesson, in Tibetan, is on the law of karma the principal of cause and effect which is the basis of all Buddhist teaching. Plant the seed and the wheat grows, says Geshe-la. From a good seed, good wheat grows. Merit arises from good actions; negative karma from bad actions. The boy debates vigorously, chastising himself with a slap on the head when he falters, then collapsing into laughter. The chirrup of a Mickey Mouse alarm clock marks the end of the lesson. When he is 14 the young lama will go to the debating courtyard, where as many as 500 monks at a time gather to debate the most abtruse points of Buddhist philosophy in an elaborate ritual of call-and-response, clapping their palms to emphasise their arguments. This will be a severe test for the young lama. There are those in Sera who still have reservations about a Western reincarnate. Osel will have to be on his mettle. ‘He must be good, says Geshe-la.

My room overlooks the courtyard; at 5.30 in the afternoon, as the sun begins to dip behind the roof of the main temple, turning the huge relief of the Wheel of the Life on its roof to gold, the monks file in to begin debating. They are still there at midnight. I lie in the darkness, listening to the voices raised in raucous disputation, argument and laughter, the sound of hands hitting palms, like waves slapping against rocks, rising from below.

I ASK PACO IF I CAN HAVE A PRIVATE conversation with Lama. ‘You must ask Lama,’ he says. ‘It’s up to him.’ Lama says: ‘4.30 tomorrow.

It is his break period; he is playing SimCity and drags himself away with palpable reluctance when I remind him of our appointment.

We sit on a sofa in his room, and he tells me about his studies, his memorisations, what he enjoys (English, science, history), and what he doesn’t (Tibetan grammar). Does he understand, I finally ask, what people say about him being the reincarnation of Lama Yeshe?

He nods gravely. ‘Yes. I understand. And are they right? He laughs. ‘I don’t know.

Do you feel any particular connection?

He gives it some thought. ‘I think, when I was younger perhaps, but now I’ve forgotten.’ Do his dreams give any clues?

‘You know, I never remember my dreams.’ Does he enjoy living in the monastery, I ask.

`I remember the first time I came to India. I was seven. And when they talked to me about coming here, I said, “Bah, India.” But then I came and I realised it was a very nice place. Now I think this is the best place for me. It’s a very good place to study. And is that what you want to do, study?

His answer is immediate and emphatic. ‘Yes, that’s what I want to do. So that in the future I can teach other people. That’s what I want to do. What do you want to teach? I ask.

‘Buddhism,’ he says. ‘It’s a good thing to teach. because I think it would help to make people happier, and I believe that’s my job, to help people.’ And how do you feel about that? I ask.

‘I like it.’ He pauses, and then smiles. ‘Well actually, I’ve still not tried it yet, but I think I’ll like it.’

IF THIS 11-YEAR-OLD SPANISH BOY IS truly the reincarnation of a Tibetan lama then it turns upside down every idea we hold in the secular West about the extinction of consciousness at death.

If it is not true, isn’t Lama Osel’s life simply an experiment in social and spiritual conditioning. But then isn’t any choice we make for ally child whether to send them to boarding-school or the local comprehensive, whether to foster an interest in playing cricket or learning the piano–similarly an experiment in conditioning’!

‘If it is not true…’ Peter Kedge considers the question. ‘Then you could say that we have made a terrible mistake. But I know that is not the case.

But is the boy being deprived? ‘Of what?’ Kedge asks: mindless television programmes? Pop music? Of normal family life, perhaps. ‘But any child who was getting the input, the education, the breadth of experience of people around him that Lama is getting would be doing supremely well, and getting the most phenomenal basis for leading their life.’ And what of his future? Peter Kedge says that Lama Osel will spend at least six more years at Sera, undergoing his monastic education. At the same time, he will be working towards a degree, either at a Western university or through an Open University course. By then, says Kedge, the Lama is already likely to be ‘on the road’, lecturing and supervising FPMT activities.

‘We are so materially sophisticated in the West, yet despite all that we have tremendous personal and social problems as a result of people not understanding what makes the mind happy, what makes the mind miserable: it’s that basic. We don’t have the basic tools for healing ourselves, but they are available in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Lama Yeshe started the work of bringing that to the West, and I’m sure that Lama Osel is going to continue that work.’ But does he have a choice?

In a sense, says Kedge, the choice has already been made. ‘Any tulku, in previous lives, has already vowed to dedicate their existence to benefit others. So choice is conditioned by that wish. His purpose in life is to benefit. Now how he chooses to do that is up to him.’

But what would happen, I wonder, if Lama Osel expressed a desire to be something other than a universal teacher; what if he expressed a desire more in keeping with usual 11-year-old ambitions to be, say, a professional footballer?

‘I don’t know.’ Kedge replies. ‘We’re pioneering something that clearly you can pioneer only if you have some vision of the future. We would have to try to be flexible to accommodate something that didn’t necessarily fit into that, but a professional footballer…? Ijust don’t know.

When I ask his father, Paco, the same question he considers it carefully. ‘I think it is not possible for him to go the wrong way,’ he says at last. ‘Whatever he chooses, even if we don’t understand it immediately, he will have chosen it because it is the best way to help people. This is what Lama wants.’

WE CRAM INTO A MOTORISED RICKSHAW and make an expedition to a nearby lake, to feed the fish. On the journey back, Lama squats in the front beside the driver, recklessly swinging out of the cab. Shortly before entering the gates of the monastery he orders the driver to stop, and climbs into the back. It would not be appropriate for a lama to be seen by other monks riding shotgun in a rickshaw.

On our return, he receives two Western devotees in his room. Neither his father nor Pemba is there; Lama Osel is quite capable of fulfilling such duties on his own. He sits crosslegged on his bed-cum-dais, calmly regarding his visitors as they prostrate before him. The woman, from Switzerland, reminds him that she came to see him three years ago, when she had no money. She was able to write and sell an article about their meeting; now she wants to offer him some of the proceeds. The young boy smiles at her. ‘I don’t need any money,’ he says. ‘Do something useful with it.’ He gives her a token of his blessing, a red silk cord, which she ties around her wrist.

Afterwards I ask Lama, why does he think people prostrate themselves before him? He considers the question carefully. ‘Because they have faith in Buddhism,’ he says.’And I have a responsibility because of that.’

At dinner that night, Lama proposes a conundrum: a father gives his three sons a rupee each and tells them to come back with something useful that will fill the room. The first son returns with straw. ‘It makes me sneeze,’ says the father. The second son returns with cloth. ‘It makes me itch,’ says the father. What, Lama asks, did the third son return with? I say I have no idea.

‘A candle,’ says the 11-year-old boy, smiling beatifically. ‘To fill the room with light.’

- Tagged: tenzin osel hita

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.Don’t think of Buddhism as some kind of narrow, closed-minded belief system. It isn’t. Buddhist doctrine is not a historical fabrication derived through imagination and mental speculation, but an accurate psychological explanation of the actual nature of the mind.