- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

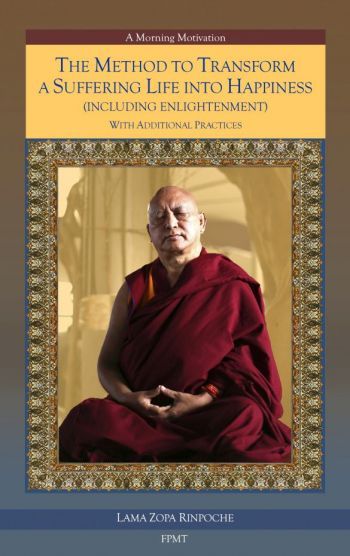

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

When we study Buddhism, we are studying ourselves, the nature of our own minds

Lama Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

Reborn in the West

Reborn in the West – Part I

by Vicki Mackenzie

The last time I had seen Lama Osel was in 1988 on the steps of the Kopan gompa, as I was putting the finishing touches to my book about him and his previous incarnation as Lama Yeshe. He was then just three years old and had announced, quite clearly, that he was going somewhere where there were big mountains and cows, ‘far, far away’. I didn’t know what he meant. Nobody had any travel plans for him. Was it fantasy, some active imagination on Lama Osel’s part? In fact, a few weeks later the Nepal government canceled the visas of all foreigners living in Nepal and Lama Osel, born in Spain, had to leave in a hurry. He went to Dharamsala in north India, once a hill station of the British Raj and now the home of the fourteenth Dalai Lama, his government-in-exile and a thriving Tibetan refugee population. In terms of travel time in that sub-continent it was indeed very far away. With the mighty Himalayas as a backdrop, and many a cow passing by, Lama Osel had obviously had some premonition of his next home.

This was the remarkable child who in the first few years of his life had been recognized by the Dalai Lama and Lama Zopa Rinpoche as the reincarnation of Lama Thubten Yeshe. He had been scrutinized by the pundits of Tibetan Buddhism and put through the traditional tests meted out to would-be tulkus, and had passed everything with flying colours. At the age of two he had been enthroned with as much pomp and ceremony as a British monarch, and had taken his place as one of the most prominent and unusual spiritual leaders of our time. From then on the former Western students of Lama Yeshe, and an increasing number of interested ‘outsiders’, would observe the Spanish boy lama in minute detail, watching for signs of authenticity and waiting for slip-ups.

Lama Osel was, after all, being held up as the most prominent example of reincarnation in our midst. While the other Western tulkus were quietly getting on with their mission, Lama Osel, on the other hand, seemed to have an extra dimension to his purpose on earth. His was very much the public face of reincarnation, in the spotlight almost since birth. This he took to with inordinate ease. From the time he was a baby and his identity was revealed he had faced public and press, crowds and disciples with a grace and detachment that were, quite obviously, completely natural.

I pondered on the fact that Lama Yeshe had, without doubt, been one of the biggest and earliest transmitters of Tibetan Buddhism to the West. His unusual and remarkable skill at putting across the ancient wisdom of his religion in Western terms, together with his charismatic personality, had inspired a huge number of followers and eventually a worldwide organization. It followed, therefore, that his reincarnation would also be high-profile, gregarious, at ease with the public, and ready to make his message known on a wide scale.

Still, it seemed a heavy burden for one so young, and I sometimes worried that my book increased his fame. Was it right? I asked Lama Zopa Rinpoche. Was it good for him? And Lama Zopa had answered that it was all part of Lama Osel’s purpose here on earth, this time round.

Somewhat reassured, I continued to keep track of the little lama as he darted about the globe visiting his former students and demonstrating by his very being how this extraordinary new phenomenon of the tulku was working in the Western world. The next time I saw Lama Osel was in Pomaia, a country town nestling in the Tuscan hills, where the Italian students of Lama Yeshe had founded a centre. The Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa was housed in a large and impressive villa, and in the summer of 1989 it was full of visitors listening to the teachings of Lama Zopa and waiting for Lama Osel to arrive. A year had passed, and physically Lama Osel had changed. He had lost the baby plumpness which made his small figure strangely similar to the round shape of Lama Yeshe, and the leanness of boyhood had set in. He was growing up.

Life, too, was becoming more serious. Lama Osel had a job to do in this life–the job of transmitting the holy Buddha dharma to the West–and the training for that awesome task was stepping up. He had been set on his way in Dharamsala, when HH the Dalai Lama had taught him the first letters of the Tibetan alphabet. This act secured the great man as Lama Osel’s root guru, for, according to Tibetan belief, the person who gives you the means to understand the precious dharma is the foundation of all your attainments. At that time Osel was also receiving daily teachings from Lama Zopa Rinpoche and from an extremely tall and handsome monk called Yangste Rinpoche who was hailed as the reincarnation of a former teacher of Lama Yeshe. Lama Osel was devoted to this gentle young man. All in all, the spiritual talent lining up to teach Lama Osel was impressive indeed.

Now he was four, and his maturity was pronounced. He was bilingual in Spanish and English and had daily Tibetan lessons both in the rudiments of scripture and language. Maria, his mother, along with some of her other children, had driven from Spain to Italy to see Lama Osel. Together we crept up to the room where he was receiving his daily lessons in Tibetan prayers from Basili Lorca, his attendant, and waited outside the open door. Lama Osel had his back to us and was clearly intent on his studies. We watched and listened as Basili recited the lines of the prayer that Lama Osel had to memorize. The child got so far, and then stuck. Patiently Basili repeated the lines. Again Lama Osel stopped at the same place. This happened several times–and then Lama Osel raised his fist and beat his head several times, saying in a voice of sheer determination, ‘I must get this into my head.’ Maria and I looked at each other in surprise. Here was no coercion. Here was a very little boy totally determined to learn a difficult prayer in a foreign language. The diligence was coming from him. Over and over again he spoke the Tibetan words, trying to get the pronunciation right. He was neither bored nor frustrated–just patiently committed to mastering the task at hand. He turned round, saw his mother, grinned–and then instantly turned back to his studies. He might not have seen her for months, but the lesson took priority. His concentration, as always, was remarkable.

Maria commented that she was surprised to see her young son taking his studies so seriously. ‘It is unusual to see a child of his age feel so much responsibility to learn,’ she said. It was, in fact, very touching.

Watching Lama Osel being so assiduously tutored raised the same vital questions: if Lama Osel was the reincarnation of Lama Yeshe, why was he having to learn the prayers anew? Later I had the chance to put the matter to an extremely high reincarnated lama, Ribur Rinpoche, who had once been the abbot of fifteen monasteries in Tibet. Then the Chinese had imprisoned him for some fifteen years, during which time he had been tortured for months on end and had his hands tied behind him day and night. It was reported that even under such dire conditions he had remained serene throughout, and had even cheered up his fellow prisoners. He seemed as good a person as any to ask about the intricacies of the workings of the mind. ‘If reincarnated lamas have developed their minds to such a high degree, why aren’t they reborn possessing exactly the same qualities” I enquired.

‘The point is,’ he told me, ‘they don’t come as enlightened beings. They come as ordinary beings, and so they have to rely on a teacher. It’s the same for all of them, including the Dalai Lama. They have to train – they have to bring out their qualities. It’s very important. The tulkus come back through the power of loving kindness, compassion and altruism, whereas ordinary beings are reborn through the power of karma. This means they come back exclusively for the means of living beings. Since they do come again they don’t come as enlightened, because they have to show how a person should train.’ The ultimate test for Lama Osel, however, would be the benefit he would bring to others. After all, we had been told, that was the only reason why he had been born.

Certainly at this age he was already showing signs of exceptional kindness and caring. It had been there as a toddler, when he anointed my mosquito bites with ointment, when he worried about animals being killed for food. It hadn’t diminished one jot. Shortly after arriving, Maria told him her brother was ill in hospital in Spain. The effect of this news on Lama Osel was electric. He stopped what he was doing, went over to Basili, pulled on his sleeve urgently and said he wanted to leave immediately! He needed to go to Valencia to see his uncle and say prayers for him. Basili had a difficult time persuading him it wasn’t possible. Later I learned that Osel always wanted to go to people who were sick.

Over the next few days I watched Lama Osel’s growing sense of his role in life. As a baby he had naturally, almost automatically, been a tiny lama; now he was becoming conscious of it. He was perpetually smiling at people and seemed to mean it. He would stop what he was doing to greet newcomers and give them a blessing. His arrivals and departures by car were accompanied by much waving–just like those of a well-groomed royal child. He graciously posed for pictures whenever it was demanded of him. He happily passed round tea and biscuits if he received visitors in his room. In fact he was just like Lama Yeshe–warm, hospitable, considerate, outgoing and communicative, reaching out to people whenever and wherever he could.

But the most interesting development from my perspective was his growing assumption of the role of leader. Whereas before he had been happy to play with people, or by himself, now he was organizing games and gathering the youngsters of the centre around him. They flocked to him naturally, drawn by his magnetism and his infectious sense of fun. He was indubitably ‘the boss’. Was this to be his new generation of followers? One of my most graphic memories of this time was the sight of Lama Osel loading up a cart with small children and, with the help of the bigger ones pushing from behind, pulling his cartload around the grounds while he led them in Tibet’s most famous mantra, ‘Om Mane Padme Hung’ Homage to the Jewel in the Lotus–which they belted out at the top of their voices!

His spiritual precocity was still in evidence. One afternoon he got hold of the pendant of Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion that his mother was wearing. ‘Take this off,’ he commanded. ‘It isn’t blessed. Only the Buddhas can bless it,’ he said as he put the pendant on his altar in front of all his Buddha statues. Who knows how he knew it hadn’t been blessed?

The same precocity reappeared during the puja, the long, ritualized religious ceremony held to pay homage to Osel as the guru. As always, Osel was surprisingly at ease sitting on the throne for some three hours at a time, dressed in the regalia of a high lama and watching Lama Zopa Rinpoche out of the corner of his eye for the cues to play his damaru and bell. At intervals he grinned at some monks and winked at others (a newly learnt trick), mixing comedy with the spiritual like Lama Yeshe. He rocked back and forth on his cushion, moving to some inner felt rhythm while reciting the Tibetan prayers he had learnt. He tried hard to do all the complicated hand mudras, attempting to fulfill his role with a touching sincerity.

It was when the selected monks and nuns stood to offer him gifts of food and incense that I saw the profoundest transformation. His whole demeanour changed. An air of exquisite serenity came over him. The atmosphere in the room became charged with a tangible stillness as, with downcast eyes and an aura of curious ancient wisdom in a body so young, Lama Osel listened to the chanted requests by the standing monks and nuns to please live long and help all sentient beings. This was Italy in 1989, but for a few minutes it seemed as though we had ‘intersected the timeless moment’, as T. S. Eliot said.

Then it passed. The puja was over. Lama Osel yawned widely, stood up from the throne and with a clenched fist above his head made the victory salute to Pende, the American monk who had been teaching him about baseball culture. It was back to normal.

Later, looking through the photograph album, I got a glimpse of the very unusual life that Lama Osel had been leading in the past year. A world tour had taken up much of the twelve months. There he was sailing in Hong Kong, there in Los Angeles at the Kalackara Initiation given by HH the Dalai Lama, there at Disneyland being hugged by Mickey Mouse, there again in Hong Kong with his arms around a young Chinese boy, the reincarnation of one of his closest friends from his previous life–the warmth between the two young boys was unmistakable. There he was making small Buddha figures with Lama Zopa Rinpoche; there he was in France playing computer games with a monk; there he was in Madison, USA with his former teacher, Geshe Sopa; there he was in Holland imitating a person meditating; there he was in Germany … and so on. It was a sophisticated life, but one which his attendant Basili Lorca insisted was not making him spoilt.

‘He can deal with the travelling easily, although the change in food sometimes upsets him,’ said the Spanish monk who had become mother, father, friend and teacher of Lama Osel. ‘He gets a lot of attention, but he is too kind and too intelligent to be spoilt by it.’

It was Basili who was with Osel more than any other person. Did he notice any further signs of Lama Osel being a reincarnated high lama, Lama Yeshe perhaps?

‘It depends on the situation. Environment is very important to him. Lama Osel, perhaps more than other children, is very quick to pick up the atmosphere and learn from the way others are. When he is with boisterous children he becomes noisy. When he is with other rinpoches, such as Ling Rinpoche, the relationship can be very good.

‘In Dharamsala, where he was surrounded by lamas and scholars, he was much more like a lama than a small child. He would do clever things and give answers that a child wouldn’t give. Of course, tulkus never say clearly who they are,’ he said.

‘At one point in Dharamsala a very high and old rinpoche came to do a retreat. During that time Osel woke up one morning saying his name–actually chanting his name. He wanted to go and see him and take him a katag. He insisted. So off we went. Sitting before this holy man, he enquired if he could ask a question. The rinpoche said “Yes.” “Can you see the minds of all sentient beings?” Lama Osel asked. The rinpoche was very surprised at such a question coming from a young child. “I wish very much that I could. I am trying to achieve that,” he replied. Lama Osel then saw a picture of the Dalai Lama in the rinpoche’s room and remarked that the Dalai Lama was his guru too.

‘But actually it is in the small things that I see the greatest signs,’ Basili Lorca continued. ‘One night after I had washed him, washed his clothes, given him supper and put him to bed–the usual routine–he said, “Thank you, Basili, for all you do for me. Thank you. You are so kind.” This is not the usual behaviour of a child,’ he said.

Anyone who knew Lama Yeshe could recall his extraordinary ability to thank people. Visions flashed back of him coming into the Kopan meditation tent, beaming at us left and right, hands together and saying, ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you so much.’ Gratitude, I later discovered, is a hallmark of true spiritual realization. Lama Yeshe had it. He not only thanked people for the obvious things, but he would find gratitude in himself for the most obscure reasons like someone sunbathing, or a traffic cop handing him a speeding ticket! For a small child to be aware and appreciative of the kindness of others was indeed most unusual.

Not that he was always a paragon of virtue. His mischief level was as high as his spiritual one. Maria, Basili and I watched as he occasionally hit out at a child who wanted a toy he was playing with. He often wanted to win at games, and he could be extremely bossy at times too. It seemed normal enough.’I have to keep strong discipline. He’s strong-minded, and needs strong means of control,’ said Basili.

The ‘strong means of control’ was spanking. Lama Osel frequently felt Basili’s hand on his bottom. While many of us disliked the amount of physical punishment he received, Lama Osel had his own disconcerting way of dealing with it. He would often turn round to Basili and say, ‘I am not my body’, or ‘Thank you, Basili, for beating me.’

When tackled about the correctness of hitting him, Basili was unrepentant. He had been told by Lama Zopa that this was the correct way to reprimand Lama Osel, the way that all Tibetan children were taught to distinguish right from wrong. It was the Spanish way, too. ‘The Dalai Lama, Lama Zopa, Lama Yeshe, all the great lamas have been spanked. It’s normal. The important thing is that it is not done with anger,’ he said.

The other contentious issue surrounding Lama Osel was the fact that he was separated from his family. In Tibet it was an accepted part of their culture that tulkus, when found, would be taken back to their former monastery to continue teaching and guiding others as they had in their previous life. The child himself (for it was usually a ‘he’) was normally only too willing to return to his former home, in spite of protestations from some parents. For Westerners, however, the fact that a small child like Osel was living apart from his mother and father was disturbing.

Maria and Paco were unusual parents. As a mother Maria had always expressed an unconventional belief that children should not be crowded, but given ‘space’. She was completely and sincerely unclinging. She loved her children, but she did not need them to fulfill her. In fact, although she had babies with ease, she had never actually wanted a family. They just came, aided by her innate dislike of contraception or anything ‘unnatural’. Besides, both Paco and Maria were devoted followers of Lama Yeshe. Inspired by his message of universal love and wisdom, they had established on the highest mountain in southern Spain a retreat centre which was open to practitioners of all faiths. With their devotion to Lama Yeshe and their trust in Lama Zopa it had not been so difficult for them to place their special son in Lama Zopa’s care.

They had travelled en famille to Nepal to be near Lama Osel when he was in Kopan, but had been forced to return to Spain when the Nepalese government suspended ail foreigners’ visas. It had been a year since Maria had last seen Lama Osel, and now, in Pomaia, I asked her how she had coped with the separation.

‘I know that real love is not attachment, and I try to develop this feeling with regard to my son. I have to share him with everyone,’ she said. ‘To be with Lama [Osel] for two hours is real happiness for me. To be able to come here to Italy and be near Lama for a few days gives me incredible joy. If he were with me all the time it would be just as it is with all my other children. We get angry and frustrated with each other, we never really have quiet moments together. So, I like this position very much.

‘Someone is taking care of him perfectly. He is happy, healthy, clean, kind to everyone. I am delighted.

‘Besides, after one year of being away from him I realize that Lama can manage very well without us. Lama has a very wide emotional world. He is not like other children who only have their immediate family to interact with. Lama has Lama Zopa Rinpoche and a global family. He also has no time to fret. His life is completely full.’

If Maria was sanguine about being separated from her son, Paco was feeling the wrench strongly.

‘Paco misses him more than I do. I can intellectualize the situation and accept it, but Paco is more emotional. It goes straight to his heart,’ she admitted.

She was right about Lama Osel not missing them. As always, he had shown an uncanny nonchalance about being parted from his family to lead a monastic life. This had been particularly noticeable when he was around two or three, the years when you would expect a small child to be devastated to find himself without his family, especially his mother. On several occasions in Kathmandu I watched with fascination the way he reacted when, after spending time with them, it was time for him to leave. I never saw him hesitate to say goodbye and get in the car to drive away. In fact he seemed pleased to get away from the hubbub of that large family to return to the peace of the monastery. Now, in Italy, the same dispassionate love was there.

It was not that he had no feelings for his family. He played with his siblings happily and always paid particular attention to his younger brother Kunkyen (Maria and Paco had given all their children Tibetan names), bringing him fruit and drinks and generally behaving in a deferential manner towards him. Whenever I returned from Kopan after spending time at Maria and Paco’s house, Lama Osel would ask: ‘Did Kunkyen bless you?’ It was rumoured that be too was a ‘special child’, although no official overtures had been made towards him.

A year later Lama Osel’s fondness for Kunkyen had not changed. ‘His first question is to ask how he is,’ reported Maria. Kunkyen was now three and, according to Maria, very strong-willed. ‘He speaks a lot. He’s like an actor, very funny–he bends his ears, things like that.’ Here was another child to watch, I thought …

I asked Maria what struck her about Lama Osel’s development in the twelve months since she had last seen him.

‘I notice that his mind is always positive. He seems to be able to transform any situation into a party,’ she replied. And then she remarked on a quality that I too had noticed: that Lama Osel didn’t seem to be touched by the strength of his emotions like most of us are. If he is unhappy or sad it lasts for a few seconds and then he is out of it. It is almost as though he is wearing a mask for our benefit–to be normal.

‘He doesn’t have the same concepts of suffering that we have,’ said Maria. ‘He is completely in the moment. He wakes up immediately. If you tell him to stop playing he says, “OK.” If it’s time to go to sleep he says, “OK.” If it’s time to go it’s OK. He can change from one situation to another without any problem. This is very unusual.’ As for her son’s identity, Maria is clear: ‘I don’t have any doubts that Lama Osel has the mind of Lama Yeshe, but it’s still developing. I still think of Lama Yeshe when I think of my guru. Maybe when I receive real teachings from him I will consider him my guru. Right now, however, I still call him carino!’ she said.

Reborn in the West – Part II

by Vicki Mackenzie

Another year passed before I saw Lama Osel again. He had spent the intervening months more quietly in a Tibetan monastery in Switzerland called Tarpa Choeling, set up by the late Geshe Rabten. The high mountain air, the healthy food, and the peace and routine of monastic life had suited him well. But in August 1990 Lama Zopa was coming to Holland to teach at the Maitreya Institute, founded by the Dutch students of Lama Yeshe in the beautiful woodlands of Emst, and Lama Osel and Basili had travelled there to be with him.

Lama Osel had grown up considerably and was taking charge more than ever. I arrived as a puja was about to begin, and hurried to join in. This time Osel didn’t wait for anybody’s cues. He launched right in, reciting Tibetan prayers one after the other at an impressive rate. I looked at him afresh and noticed that, in some way, he now seemed to be Lama Zopa’s equal. Thankfully, the sense of humour was still intact. At one point he got a fit of the giggles which he successfully controlled. He grinned, made faces and struck a mock meditation pose–which looked hilariously like Lama Zopa. He knew it, but interestingly didn’t laugh himself.

The discipline and the concentration which had been visible a year earlier had developed. A glass of orange juice was put in front of him, but it was an hour before he took a sip. At the back of the large room a group of children had got bored with the ceremony and were playing. He made no move to join them, nor did he cast any envious glance towards them. Instead he blessed each of them as they came up to him at the end to offer him the white scarf.

At the end of the puja Lama Zopa Rinpoche made a speech.

As always, behind the quiet delivery was a potent message: ‘Today we have offered a long life puja to Lama, who passed away in his old aspect and has returned as a guide in his new aspect. Although I have a little dharma knowledge I travel from one country to another around the world. But until Lama Tenzin Osel Rinpoche is ready to teach sentient beings in the West and in other places, I plan to continue like this,’ he said.

‘We invite highly qualified teachers to be guest teachers at our centres, and when they come we receive them and we accept their kindness in helping us. But we must never, never forget that this is Lama’s incarnation. Lama who has returned to us in his new form. We must not forget the one who has created all these centres.

‘There are so many sentient beings who have come into contact with the dharma that we should not let Lama, who has come back in a new form, be forgotten while we are so fortunate in meeting other qualified lamas.

‘I think it is my responsibility to say these things because Lama brought me to the West so often in the past to create this organization for his Western students.’

It was, it seemed to me, not only a promise that Lama Osel would indeed be teaching one day, but a warning that in the interim we must not lose sight of who our ultimate teacher was. What Lama Zopa was doing was shoring up the edifice of the worldwide structure of centres that Lama Yeshe had initiated, making sure it stayed steady until Osel could take the helm. Looking at the young boy sitting next to Lama Zopa, charmingly putting his hand up to his ear as if sneaking to catch words he was not supposed to hear, it sounded a dizzying plan. Osel was still five years old. So many things could happen.

I received a potent reminder of the Buddhist law that nothing stays the same when I met Maria again. Life might have been running smoothly for Osel in the past year, but she had been dealt a severe blow. Maria had discovered a large tumour in one of her kidneys. She told me the precise measurements: 8cm x 7cm x 6cm. It sounded enormous. The doctor advised her to have it out immediately. But, with her typical dislike for medical interference already evidenced by her attitude towards contraception, Maria had decided to wait before making her decision. In the meantime, with her usual sublime ease, she had produced another child, her seventh. She had also started up a tourist business in her home town of Bubion, to cater for the growing number of visitors who were beginning to discover the lovely little town.

Lama Zopa had then visited Spain, and she went to meet him to tell him of her sickness and seek his advice. ‘If the guru said I should have an operation then I would have, even though I don’t like doctors or hospitals. But Lama Zopa told me that this sickness was full of blessings for me. “It will help you practise. Now is the time to do a retreat–to control the illness,” he said.’ His words struck home, and for the first time in her life Maria was planning to plunge herself into serious meditation.

In fact the whole year had been difficult for Maria. The previous Christmas Eve she had had a car accident. She had been driving Lama Osel and Basili back to Bubion from Madrid when a car veered out of a side street in Granada and hit them. The driver had been celebrating for a good few hours. Maria had been jerked into the steering wheel; Basili had lurched forward and hurt his knee; and Lama, who had been sleeping in the back, fell to the floor, not hurt at all. Nevertheless they decided to go to the hospital to be given a check-up.

What happened there was extraordinary. The four-year-old Lama Osel took control. He had approached the doctor and said: ‘Please take care of my mother, who has a pain in her side, and Basili, who has hurt his knee. I have nothing wrong, but you need to check them.’ The doctor was rather nonplussed about being given orders by such a small patient and replied that he should be examined himself. ‘No, there is no need. But please look after my mother and Basili,’ he insisted.

A little later the doctor heard a knock on the door of the room where he was looking at X-rays of Maria and Basili. Osel walked in. ‘Please can I enter, because I am very interested in this sort of thing,’ he announced. The doctor took a second look, then recognized the child whose face was well known all over Spain. Suddenly this unusual behaviour became clear to him.

Lama Osel was also still capable of surprising even those closest to him with sudden ‘revelations’. One day when he was in Switzerland his father Paco, an Italian monk and Basili took him to lunch at a restaurant with a balcony overlooking a valley. Lama Osel sat watching some birds flying down to the balcony looking for scraps to eat. Amid the general conversation Osel began to speak in a tone that made them all stop and listen. ‘Before,’ he said, ‘many, many Buddhas came into my body, then I became tiny and entered into my mother’s womb. Then I came out.’ He paused, then added, “Before, I was Lama Yeshe. Now I am Lama Osel.’ The others were speechless. The birds flocking down to the balcony had obviously triggered off a memory of something that had happened before he was born. Nobody could be sure what exactly he was talking about, but all those present knew that when he was dying Lama Yeshe had performed his profound meditation where he would have visualized the Buddha Heruka, his personal practice, dissolving into him several times. According to the esoteric guidelines of tantric Buddhism, mastery of this highly complex meditation is essential in order for the spiritual adept to dictate the precise conditions of his next rebirth. Was this the many Buddhas dissolving into his body Lama Osel was talking about?

His statement about being Lama Yeshe before and Lama Osel now was one I had heard earlier in Kathmandu when he was only three. He had been playing with his brother Kunkyen and I had asked him outright if he was the reincarnation of Lama Yeshe. ‘I am Tenzin Osel, a monk,’ he had replied with great solemnity. ‘Before, I was Lama Yeshe. Now I am Tenzin Osel.’ I had marvelled then that at such a young age he had managed to find the words to express the complicated process of reincarnation. The continuity of the two beings was present, but the identification of the two personalities was different. I marvelled again now, when I heard the remarkable words that Osel had uttered after looking at the birds.

A few months later I saw him when he stopped over in London en route for the next stage of his extraordinary life. He was on his way to southern India to Sera monastery to begin his formal Tibetan education. He slipped his hand in mine as I showed him some of the sights. The swarming pigeons at Trafalgar Square did not impress him at all, but the creepy-crawly exhibition at the Natural History Museum did. He was engrossed by the minutiae of the insect kingdom, and would have stayed looking at the exhibits for hours had we allowed him.

He had duties to perform as well. He hosted a children’s hot-chocolate party at the Jamyang Centre, in Finsbury Park, where he sat rapt in front of a video of The Snowman, twice. Although he had come down with a heavy cold he thanked the photographers for ‘taking the trouble to come’ and he willingly presided over a puja, although he must have been feeling awful. It was on this occasion that I noticed for the first time how adults, especially newcomers, often projected their own childhood experiences on to Osel.

One woman I spoke to said it was cruel to subject a small child to such a lengthy ‘ordeal’ when he should be tucked up in bed. She had been sent to boarding school at five and had been traumatized in the process. Another man commented that he thought Lama Osel looked bored by the whole procedure–and then added that he had spent much of his childhood in a similar state. Yet another woman didn’t understand a word of what was going on but went away feeling inexplicably happy. As it was impossible that Osel was incorporating all these varying conditions I began to wonder if he was acting as a mirror, reflecting back to the observer states of minds and emotions that they possessed. If so, then he was truly fulfilling the role of the guru–for the real guru, the worthy, honourable guru, functions to reveal the disciple’s own inner nature and thus to show what must be confronted, worked on or acknowledged.

For several happy hours I watched him at play: it was a fascinating spectacle. Someone had given him a model aeroplane designed for a seven-year-old. He sat down by himself to assemble the pieces, following the instructions and diagrams. When he reached a certain point he got stuck. Much to my surprise, he did not throw a tantrum or get frustrated as most children of five would have done; instead he calmly undid all that he had done and started from the beginning again. His concentration was immense and unusual. I recalled that concentration comes from hours of meditation. The ability to focus for hours at a time on a single task is the territory of the yogi. Could what I was witnessing be the result of Lama Yeshe’s past efforts? Osel got to the same point in his plane-building, and again he could go no further. Again he took the model apart. Twice he built the aeroplane, and twice he disassembled it. On his third attempt he finally gave up, defeated by the difficulty of completing the exercise. He thrust it into Basili’s hands. ‘You do it!’ he commanded.

Later I overheard someone talking to him. ‘What do you want to do when you grow up?’ they asked.

‘Give teachings,’ came the immediate reply. Then he added, seriously, ‘But not now. Later.’

Did he know the Dalai Lama, and if so what did he think of him, they enquired.

‘He is my guru,’ said Osel almost dismissively, as though this was so obvious that it was hardly worth asking.

Later, he got up and led me by the hand upstairs to show me a photograph of Lama Yeshe hanging on the wall. ‘That’s me, before,’ he stated in a matter-of-fact way. ‘Then I got sick.’ He did a mime of someone getting weaker and weaker and sagging. ‘Then I died and they put me in a stupa and set fire to it,’ he said, tongue lolling out. ‘And now I am here,’ he added cheerily. It was impressive. But at this age one could not be sure how much he had been told and what he intuitively knew. From now on, I thought, demonstrations of past-life recall would never be as thoroughly convincing as those he had given when he was a baby.

I saw him again over Christmas at Varanassi, also known as Benares, that ancient crumbling Indian city on the banks of the Ganges. I was on my way to Australia, Lama Osel was on his way to Sera monastery, and a vast crowd of 150,000 Tibetans were on their way to attend the Kalachakra Initiation to be given by the Dalai Lama at Sarnath, the place where the Buddha delivered his first teaching after reaching Enlightenment. The Kalachakra Initiation was one of Tibet’s most esoteric and difficult practices, in which the Initiator would harmonize the inner elements of the body and mind to bring about harmony and peace in the outer world. The Dalai Lama had been performing this ceremony across the world in an attempt to stop humankind’s destructive tendencies. Now it was Lama Osel’s little figure which strode confidently on to the stage in front of that vast throng to present the representative offering to the great man.

Later he dressed up as Father Christmas to give presents to people in his hotel, and he ordered hot milk from a stall to be sent to the stray dogs milling around outside. On a more official note, he hosted a lunch party for all the young reincarnated high lamas who had come to the Kalachakra. It was an impressive gathering. They were ail there; Ling Rinpoche (previous senior tutor to the Dalai Lama); Trijang Rinpoche (previous junior tutor); Song Rinpoche, who had been very close to Lama Yeshe and presided at his funeral; Serkong Dorje Change; and Serkong Rinpoche, the marvellous lama whose furrowed face and large, pointy ears had supposedly been the model for Yoda in the film Star Wars.

Curiously, their ‘predecessors’ had all passed away around the same time. It was said that they had chosen ‘to die’ in order to remove serious obstacles that were threatening the Dalai Lama’s life. They had been the cream of the Gelugpa hierarchy, the lineage holders, all of them towering masters of meditation and scholarship. They had all been reborn around the same time as well. Now their reincarnations were assembled on the lawn of this smart Indian hotel.

‘That’s the entire future of the dharma,’ remarked one perceptive onlooker. Lama Osel was among them, only his white skin and Western features setting him apart. Would they accept him, and vice versa, so easily when they were all old enough to realize the difference?

Maria too had arrived–to do her retreat in Bodhgaya. She looked well, but told me that apart from the tumour on her kidney she now had a secondary tumour on her brain. As she had refused surgery and medication the doctors had given her only six months to live, but this had not upset her at all. She was putting all her faith in the spiritual practices on which she was about to embark. Lama Zopa had told her to offer up her sickness, to use her tumours as a vehicle for taking on the sufferings of others.

This advice immediately took my mind back to Medjugorye, the small town in former Yugoslavia where the Virgin Mary has been appearing to six young people daily for a number of years. Fascinated by this phenomenon, I had gone there in my capacity as a tourist to see the site for myself. I had interviewed the visionaries, one of whom, Vicka, a vivacious girl of twenty-four, told me about the brain tumour she had developed. For months on end she felt sick and was continually fainting, but she kept up her cheerful disposition, insisting on talking to the pilgrims who came to hear her message.

She had told me that the Virgin Mary, or Gospa as she was called in Medjugorye, had asked her to offer up her brain tumour for the sickness of the world, and that it would be cured on a specific date. Vicka had duly written down the date of her promised cure, sealed it in an envelope and given it to the local priest for safe keeping. In the meantime she had refused offers of free treatment from a Harley Street specialist in London.

Her faith was rewarded. On the exact date that she had written down, the tumour suddenly vanished. Today Vicka radiates good health, and that inner joy which is invariably the signature of true spiritual experience. I wondered how Maria, the mother of Osel and six other children, would fare.

During the time we were at Varanassi we had our own teaching on death and impermanence. Lama Zopa’s mother passed away literally in our midst. It affected us all deeply especially Maria, the mother of the other famous lama.

We had all come to respect the tiny, frail, almost blind old lady known as Amala, who had insisted on making the long, arduous journey from her home near Mount Everest to the hot, dusty plains of India to see the Dalai Lama and receive the Kalachakra Initiation. ‘She is sleeping in a corner of a roof–crowded in with all the Kopan boys. Although she is the mother of Lama Zopa, she refuses to have a separate room. She says she is no one special. It made me very humble,’ commented Maria.

On the last day of the Initiation, Amala had received personal blessings from His Holiness the Dalai Lama. At 10 p.m. that evening, at the conclusion of the Kalachakra, she passed away, her face illuminated by serenity and peace. She had received what she had come all this way for and had died saying the mantra that she had uttered millions of times throughout her life: ‘Om Mani Padme Hum’, the sacred words of Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion.

It was a mark of Lama Zopa’s love for his students that he turned what could have been an occasion of private grief and recollection into a public event: he allowed us into the small room where his mother’s body lay in the sleeping bag in which she had died, buried under piles of white scarves given in respect by the visitors. In spite of my apprehension at seeing a dead body, I was surprised to find the room filled with a sweetness, a delicacy and a tangible aura of something very vital, yet at the same time peaceful, going on. It remained like that for three days, when suddenly the expression on her face changed and with it the atmosphere in the room. At this point Lama Zopa Rinpoche announced that Amala had finished her meditation and had ‘succeeded’ in her death. It seemed a curious choice of words. In that singular phrase Lama Zopa had succinctly summed up the Tibetan Buddhist view that the death process was very much an individual challenge which could be controlled if we had the mind to do it.

The next day we were all invited to witness Amala’s cremation at the ghats on the banks of the holy river Ganges. It was a rare opportunity to contemplate the meaning of Death and Impermanence. The body, placed upright and covered with piles of wood scented with incense and adorned with flowers, took two hours to burn. A friend asked a nearby monk if she could take a photograph. ‘Yes–and use it as a meditation every time you feel depressed. It will put everything into perspective,’ he replied.

Silently I thanked Amala for giving us Lama Zopa Rinpoche, the small, saintly man who had worked so hard and given so much to us Westerners. As I looked at the smoke swirling over the sacred river and the queue of corpses lined up along its banks waiting to be burnt, I thought how short and ephemeral this life was.

There was, however, no end to mind. It continues in an ever-flowing, ever-changing stream, like the great Ganges itself. To press home this most fundamental of Buddhist teachings even further, in case we had not got the point, a few years later we were to be presented with a young boy with an exceptionally intelligent face. He was sitting at Lama Zopa’s feet in monk’s clothes. He was, we were told, the reincarnation of Amala.

Reborn in the West – Part III

by Vicki Mackenzie

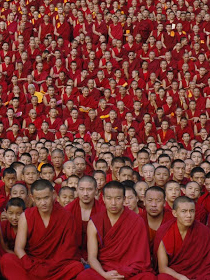

On 15 July 1991 Lama Osel Rinpoche, the reincarnation of Lama Thubten Yeshe, formally entered Sera monastery. He was six years old. As his small motorcade approached its destination, a red line could be seen in the distance. As the cars drew closer their occupants saw that it was the entire assembly of monks, who had turned out to line the road to welcome their newest incumbent. It was an honour accorded only to the highest lamas–but, it was agreed, Lama Yeshe certainly qualified due to his immense work in spreading the holy Buddha dharma across the world, and because of the prestige he brought to his monastery. To the monks of Sera, the small Western boy clasping his hands together and bowing in greeting had simply ‘come home’.

Sera was awesome place and as far away as you could get from the archetypal image of a mysterious building clinging to a mountain peak. It was as big as a town, with streets, houses, dormitories, temples, kitchens, shops and dogs: a bustling, throbbing place pulsating with the vibrant, all-male energy of vast numbers of Tibetan monks. By the time Lama Osel arrived there were over two thousand of them, and their numbers were growing yearly as more and more fled from Tibet to seek the spiritual training that was denied them in their homeland. Lama Osel had entered the largest monastery in the world.

Sera was one of the three great monastic universities that the Tibetan refugees had painstakingly rebuilt in exile. It was of vital importance. Their monastic universities were not only the womb of their greatest spiritual, philosophical and meditational masters, they were also the bedrock of Tibetan culture.

Back in Tibet it was to the original Sera monastery, on the outskirts of Lhasa, that the young Thubten Yeshe had gone when he was just seven years old. There he began his austere, highly disciplined training which would lead eventually to a worldwide mission. It was a mighty place, founded in 1419 by Jamchen Choje Sakya Yeshe, a disciple of the famous Lama Tsongkhapa, the great reformer of Tibetan Buddhism and founder of the Yellow Hat sect. Ironically, in the light of the Chinese destruction that was to follow centuries later, Jamchen Choje Sakya Yeshe was twice sent to China to teach the Buddhist doctrine to the Emperor. By 1959, when the Chinese invaded, Sera monastery held a huge population of ten thousand monks. Although a quarter of these managed to escape to northern India, among them Lama Yeshe, many died from the unaccustomed heat and diet in the refugee camps.

Those who remained were eventually given a heavily wooded area in Karnataka state in southern India, about a two-hour drive west of Mysore. They set about clearing the space and building again the seat of learning that was to preserve their spiritual heritage and maintain the strength of their spiritual lineages.

Now, after Lama Osel’s arrival, the ceremonies and welcoming parties went on for three days as the monastery officially offered him a place in their august place of learning, and in return Lama Osel offered them the traditional gifts of ceremonial pujas, food, money and tea, as well as a new well and substantial contributions to the Sera Health Project. It did not come cheap. The estimated cost of Lama Osel starting his new education was around US$50,000.

Lama Osel appeared happy in his new house, built specially for him in a quiet place on the outskirts of the monastery. It had a garden and a dog called Om Mani. On the morning after his arrival the abbot arrived at Lama’s new house to greet him personally. Lama commented that he thought everything had gone extremely well. ‘I dreamed before coming that first there was a lot of light coming up and I was down, then much light came down and I was up high,’ he said. It was an auspicious dream.

Many Western students had arrived at Sera to witness this turning-point in Lama Osel’s life. Among them were his parents, Maria and Paco. At one point during the investiture Maria and Paco stood up and walked out of the temple together–a symbolic gesture which formalized their willingness to give their child to the religious life. Although Osel had in fact been happily leading an independent life for four years now, as his parents physically turned their backs on him and walked away he looked a little wistful.

Now the serious work–the hours of study and the tough discipline–was about to begin in earnest. Lama Osel was being plunged into an extraordinary system–rich, wonderful and unique. Only Sera had the means to lay the foundation of the work that Lama Osel was destined to carry out. For only the Tibetan teaching system had the ‘technology’ for understanding the mind in all its manifold and subtle details. The expectation was that Osel would become a holder of the lineage of teachings and initiations, which was possible only by passing through the special education of a Tibetan monastery and specifically the tulku training system. More significantly, it was felt that only an education in Sera could furnish Lama Osel with the credibility regarded as absolutely necessary for his future life as a teacher. No matter how inherently gifted as a spiritual master he might be, without the thorough training and qualifications available from Sera his work would be undermined.

For all this I, and many others, quaked a little at this next phase in Osel’s life. He was after all, a Western child with a Western mind, and Sera was–well, so Tibetan. It was also steeped in the framework of a six hundred-year-old tradition which had not changed much over the years. Many of us wondered how Lama Osel, with his love of computers and Michael Jackson music, would fare within the rules and rigid protocol of this strong Tibetan experience.

Maria voiced the concerns that a few of us were feeling: ‘Lama’s temperament is free, creative and spontaneous. He learns by reason. If you explain things to him he grasps It very quickly. In the traditional Tibetan system, however, learning is done by rote. They learn all the prayers, all the scriptures, by heart– and then when that is accomplished they debate on the meaning. This is not the Western approach to education and in my view is rather archaic.’

Osel’s day was now broken into strict periods of learning: 7 a.m. get up; prayers before breakfast at 8 a.m.; Tibetan language class from 9 a.m. for two hours; then Spanish class for one hour; lunch at noon; 1 p.m.- 3 p.m. English reading, writing and maths; 5.30 p.m. lessons with his Tibetan teacher; dinner; bed at 9 p.m.

It was indeed a tough regime, with the emphasis for the first few years on memorization and getting used to the monastic discipline. He was aiming eventually for a geshe degree, equivalent to a doctor of divinity, which back in Tibet took some thirty years to achieve. Here in Sera the process had been speeded up, but still there would be years of rigorous learning and debating before Osel was through. I wondered if he would stick it out.

I thought back to Lama Yeshe, and the way he had broken with the traditional methods of teaching to reach us Westerners. He had once told me he didn’t care, that he was prepared to use any technique to get his audience to understand the Buddha dharma. That was his great appeal his ability to communicate the way of the Buddha with his whole body, with gestures, with antics, with his marvellous sense of humour and with his spontaneous acts of kindness and love. He was not a conventional lama at all, on the outside at least. He knew that Westerners were not interested in the strict Tibetan presentation of the dharma and so had found his own highly individualistic way of teaching it. Part of me baulked at the idea of Lama Osel returning to the system which Lama Yeshe had, in the outer form, moved away from.

Still, Lama Zopa had decreed quite unequivocally that it was best for Lama Osel to go to Sera. And who were we to dispute that great man, who cherished Lama Osel more than his own life? He had taken enormous care in choosing Lama Osel’s gen-la, the Tibetan geshe who was to teach the boy the Tibetan language, the memorization of texts and Lam Rim (the step-by-step guide to Enlightenment) subjects. He was a gentle, kind man and one of the best teachers in Sera. As Lama Zopa pointed out, the conditions provided for Lama Osel were all-important. So, for all its possible drawbacks, Sera had incomparable benefits to offer. We could only wait and see the outcome.

Not that Lama Osel’s Western roots were being totally forgotten. In order to help build a bridge between the two ways of life Lama Zopa, with his infinite care, had arranged for a Western tutor to be brought into Sera to furnish Lama Osel with the beginnings of a Western education alongside the traditional Tibetan Buddhist one. The advertisement placed in the top newspapers in London, New York and Australia revealed the enormity and extraordinary nature of the task:

PRIVATE TUTOR–to provide full primary education to highest international standards for six- year-old Spanish reincarnation of former Tibetan Lama Thubten Yeshe. Tuition to run in parallel with a traditional Tibetan monastic education to be provided by others. Tuition to assist the young Lama to integrate Western and Eastern curricula in preparation for a life of teaching.

Primary instruction medium English, secondary Spanish. Location South India eight months, Europe one month per year. This unusual and challenging assignment requires a person of highest integrity, five to ten years’ tutoring experience and impeccable references.

The person who won the job from hundreds of applicants was Norma Quesada-Wolf, a classicist in her early thirties from Yale University. Born in Venezuela of an American mother and Spanish father, and with ten years of Zen Buddhist meditation behind her, Norma seemed tailor-made for the job. With her husband John she moved into Sera armed with an independent study programme from the Calvert School in America, which not only set out a tutoring schedule for Lama Osel but provided means for independently assessing his progress as well.

Peter Kedge, a board member of the FPMT (Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) and long-time student of Lama Yeshe, had conducted the search for the right tutor. He explained the hopes for Lama Osel’s education: ‘Great emphasis is being placed on providing Lama Osel with a strong basic Western contemporary education so that, in his later years, the “language” he uses to explain molecular physics will be the same as when explaining emptiness–the aim being to cross the boundaries of the Eastern mind and the Western mind, exposing their similarities.’ It was a mighty plan indeed, but one could not help but be a little apprehensive at the load of expectations and aspirations that was being put on a pair of small, six-year-old shoulders.

The observations of Norma Quesada-Wolf, as a newcomer to this extraordinary scene of Western reincarnate lamas, were particularly interesting. Her first impression was of a child who played hide-and- seek, then showed her and her husband the Buddhas in his room, the watercolours and drawings he had done, and where a certain lizard lived. He then asked if they were tired from their journey, turned to someone and asked, with natural dignity, if they had been offered tea.

‘I suppose I was expecting to find a wise, very serious little figure, someone like Teddy in the J. D. Salinger story of the same name. But while Lama certainly does have this aspect, I had not anticipated how light-hearted and charming he would be,’ she said.

With professional interest she also noted what many amateur observers had seen on many occasions– Lama Osel’s unusual powers of concentration and his ability to be totally absorbed in what he was doing.

‘There’s something special about him. He has a capacity for concentration, for remembering, and for invention and imagination that seems to me to be beyond the capacities of an average child. When something holds his interest, whether it be playing with Lego blocks or doing a lesson, he just disappears into it and remains in that thing for long stretches of time, constantly thinking about it, imagining it, playing with it, and seeing it from all different perspectives.’ Her words immediately flashed me back to another time when Lama Yeshe was talking about how we perceived things. He took as his example a flower. Never has a flower been looked at in the depth in which Lama Yeshe saw it. He examined all its parts, he considered its perfume and its effect on our sense of smell and an insect’s, he talked about its aesthetic properties and how the flower had been an object of poetry, intuition, love and admiration, and how this differed from culture to culture. Through this intense and detailed scrutiny Lama Yeshe was trying to get us to see the totality of things through varied levels of meaning.

In fact Lama Yeshe had very clear views about how children should be educated. Using his graphic, idiosyncratic style of English he delineated his beliefs in a system which he called ‘Universal Education’:

A narrow presentation of the world in education suffocates children. It brings frustration and blockage that interrupts the child’s openness to learning. Children do not want to be trapped by limitations. If one shows them the reality of things which is beyond all limitations, their enthusiasm for learning will never cease and the individual will become a totally integrated person.

Any explanation is incomplete if there is no logical reference, no intellectual basis for it. Behind this base there must be a psychological explanation and a philosophical framework. Then the totality in all its aspects becomes so profound, so profound. In other words, contained in an entire subject are the essence of religion, philosophy and psychology without any separation, existing simultaneously. In this way the person becomes integrated. In the world today these have become separated. Really, you cannot separate them.

We cannot make divisions such as: you are the spiritual person, you are the philosopher and you are the psychologist. All of reality is contained, potentially and now existent, in everybody. Education should be everything to come together, not separating, not partial.

The bad in the world, in my opinion, is religion separated from life, from science, and science separated from religion. These should go together…

It was a system that was now tallying with Lama Osel’s own approach to learning.

Certainly Osel was enraptured by science in the form of anything to do with outer space, and had numerous books on space and space travel which he discussed in detail with Norma. She noted, however, that he would often put his comic book stories of Superman and Batman into a dharma context, working out the morals of the ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’ according to Buddhist belief.

He also showed an aptitude for mathematics and was fascinated by large numbers, vast distances, huge sizes and great weights–in fact, anything big. In the past few years he had also become fascinated by illusion and magic, and would often play games where he pretended to make things appear and disappear. He was also genuinely enthralled by the minutiae of the insect kingdom, as I had seen in London’s Natural History Museum, and in the evolution of species. Osel’s was a broad mind–just like Lama Yeshe’s.

Norma noted other character traits, too–Lama’s equally famous strong-mindedness, and the fact that he often wasn’t a ‘model’ child. ‘When something doesn’t interest him, it is impressive how he can invent one way after another, non-stop, to divert his and your attention from the thing at hand. He has a strong will and high spirits, and is very independent-minded. ‘

This again was reassuring. Norma was verifying what many of us had witnessed–that Lama Osel was not in any way a malleable person. He was very much his own person. It was gratifying, for one of my greatest concerns was that Lama Osel would be ‘conditioned’ into his present role, thereby detracting from the authenticity of his identity. How much more satisfactory to have a lama who was full of life and mischief and who could think for himself.

As she looked at the child who was now under her care, Norma saw further signs that Osel was out of the ordinary. On one occasion during an English lesson she was asking him for the opposite meaning of words. She would say ‘up’ and he would reply ‘down’, for instance. When she asked him for the opposite of ‘asleep’, however, he replied ‘Buddha!’ It was an astute and subtle answer, and a remarkable one for a child of his age. Not many adults are aware that the definition of a Buddha is a fully awakened being. Later she was to describe Lama Osel as a ‘brilliantly gifted child’.

As she looked at the child who was now under her care, Norma saw further signs that Osel was out of the ordinary. On one occasion during an English lesson she was asking him for the opposite meaning of words. She would say ‘up’ and he would reply ‘down’, for instance. When she asked him for the opposite of ‘asleep’, however, he replied ‘Buddha!’ It was an astute and subtle answer, and a remarkable one for a child of his age. Not many adults are aware that the definition of a Buddha is a fully awakened being. Later she was to describe Lama Osel as a ‘brilliantly gifted child’.

Educationally, in fact, Lama Osel was doing well across the board. His gen-la, Geshe Gendun Chopel, announced that his charge was exceptionally intelligent and, even though he too noticed the boy’s fondness for play, he felt that it would abate naturally as he grew older and understood the importance of studying. He also remarked that, although at first he had regarded Lama Osel as an ordinary child with the status of a tulku, since getting to know him he now considered him to be extraordinary, with an exceptionally clear memory.

But in spite of his excellent schoo1 reports, like many a small boy Osel often complained at having to study and told visitors he was ‘too busy’. Once he was overheard saying: ‘Don’t you know I learn when I am playing?’ He was, of course, absolutely right.

Reborn in the West – Part IV

by Vicki Mackenzie

For a while, in the change-over period between Kopan and Sera, a warm and funny Australian monk called Namgyal was co-attendant of Lama Osel along with Basili Lorca. Namgyal’s more artistic, less conventional personality found a link with those same aspects in Lama Osel’s nature, and the two soon formed a strong bond.

‘We used to sneak out together to eat pizzas, and we used to cook together,’ he reminisced to me one day in Dharamsala, where I had gone to interview the Dalai Lama. ‘Lama Osel, like Lama Yeshe, adores cooking. I gave him an apron which read “Never Trust a Skinny Cook”, which he loved. We used to roll out dough together to make these pizzas and he would say things like, “The cheese isn’t correct.” He is such a perfectionist! Everything has to be just so. He always wanted everything to be clean and proper. I remember him telling off the Tibetan lamas for slurping their soup, and they would laugh and laugh!’

Namgyal’s encouragement of self-expression showed results in Osel’s spiritual practices too. ‘Every day we’d fill the water bowls with water, representing the offerings of flowers, light, music, incense and so forth to the Buddhas. Lama Osel loved it. He’d invent different ways to make these offerings. He’d put the little crystal bowls in various different patterns and add colouring to the water. It took much longer, but he showed me what creativity could do to transform a fairly mechanistic daily rite.’

This was so like Lama Yeshe, who would transgress the conventional monastic rule by creating his own altars–full of diverse, imaginative objects like shells and clay animals that represented things that were precious to him. Once he put a toy aeroplane on his altar, as that was the hallowed means by which he could reach sentient beings around the globe. And, having come out of Tibet and discovered such luxurious aromas as Patou’s ‘Joy‘ perfume, he quickly discarded the usual sticks of incense for the most expensive scent that money could buy. Only the best was good enough for the Buddha.

Lama Osel was following suit. His prayers and meditations under Namgyal’s guidance were also taking a more individualistic and creative turn. One day, after offering up the mandala to all the Buddhas, Lama Osel turned to him and said: ‘Do you know what I visualized?’ ‘No,’ replied Namgyal.

‘I visualized Buddha in the sky and this mountain of ice cream and sweets and all different-coloured beautiful flowers all coming to the Buddha and entering into him.’ It was a perfect offering from a small boy.

‘I asked him once if he missed his family,’ Namgyal told me. ‘He replied, quite seriously: “Lamas don’t have families.”‘ For all the fun they had together, Osel also showed his Australian friend some of his special qualities. ‘He has psychic abilities. One night he woke up and said that some spirits were trying to push over his altar. I felt he was quite in tune with spirits, and so I accepted what he said. The next day he did a puja for them because he said they were suffering. He also told me that in my last life I was a lama in Kham, a province of Tibet. That was interesting, because it verified what I’d been told by a Tibetan oracle some time previously,’ reported Namgyal.

Other monks confirmed that Lama Osel would from time to time see into not just their past but their future as well. One said that Lama Osel had looked him straight in the eye and told him, ‘Again you are going to be a lama, and I will hold you in my arms.’ At other times he would scare them witless by declaring they were going to the hell realms–whether these were true prophecies or false no one was in a position to judge.

As time went on Namgyal saw other unusual behaviour which made him feel that Lama Osel was different. ‘Once, when we were in Kathmandu, Lama Osel saw a woman light up a cigarette. He turned to me and said, “Should I tell her that she is killing herself?” I stopped him, but when I reported the incident to Lama Zopa he said I should have let him because later, when Lama Osel is grown up and well known, she might think about what he told her and change.’

At another time he accompanied Lama Osel to Bodhgaya, the place where the Buddha achieved Enlightenment. Here they met Kunnu Lama Rinpoche, a famous spiritual master so revered that even the Dalai Lama has been seen to prostrate to him. Namgyal told me what happened: ‘When they met, Lama was completely overwhelmed with devotion towards Kunnu Lama and wanted to offer him all his toys, his watch, his torch, in fact anything that he could put his hands on! Afterwards Lama Osel said that Kunnu Lama Rinpoche was a Buddha and that he would never lose the photograph that Kunnu Lama had given him.’

After his post as co-attendant came to an end, Namgyal missed the company of his unusual charge. The intimacy that Lama Osel was able to evoke was powerful and precious. ‘For a while I became Lama Osel’s best friend. He used to tell me everything. Every night he’d confess to me all the things he’d done wrong, and his secrets like how he wanted to see girls without clothes on. I just treated these things as completely normal. He was so loving, so spontaneously affectionate. He loves being close to people. He’d lean across the table in front of others and say, “Namgyal, I love you.” I will never forget Lama’s love–never,’ he said.

Life was beginning to change at Sera, and so was Lama Osel. After Namgyal left, Basili did too on ‘advice’ from Lama Zopa. No one was sure why. Perhaps, I thought, it was to prevent any single person getting too attached to Lama Osel. Or maybe it was because a monk’s ultimate task is to lead a life of prayer and meditation, rather than to be a child-minder. There followed a series of Western monks assigned to look after the daily needs of the young Spanish tulku.

Now Lama Osel was beginning to grow up and increasingly to develop his own personality. In one way it was as if the mantle of the Lama Yeshe persona was slipping away, receding into the past, to allow the new being, Lama Osel, to emerge. We all had to see that Lama Osel was a different entity from Lama Yeshe, albeit connected in essence. Not only was he now looking very different from his ‘predecessor’, with his fine face, slim body and long, thin fingers, but he was also dropping his amenable, instantly lovable, infinitely charming presentation to the world. He was becoming a powerful force to be reckoned with.

I thought it could not be an easy process sloughing off such a strong, magnetic character as Lama Yeshe’s and the heavy cloak of projections that so many former students put on him. About this time I had a dream which might have been an indication of how Lama Osel was feeling. In it he was dressed in robes and walking along a path, his head bowed and with an air of consternation about him. He looked up and said: ‘When I was younger I knew I was Buddha, but now I am not so sure.’

The lines of William Wordsworth’s famous poem ‘Intimations of Immortality’, learnt at school, came to mind:

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

Shades of the prison house begin to close upon the growing boy…

The sentiments weren’t entirely Buddhist, but the message was remarkably similar.

Osel was now challenging nearly everyone with whom he came into contact–by a word, a look, a rebuke, a refusal to cooperate. No longer Mr. Nice Guy, he was throwing people back on themselves. No one found it very comfortable. Everyone had to admit, however, that his mind was becoming increasingly sharp, his perceptions uncomfortably accurate and his power undeniably great. The stories that emerged from those who saw him at this time illustrate the point.

‘Over the past year or so he has been incredibly wicked to me,’ reported Robina Courtin, a much-loved and respected nun, instrumental in setting up the FPMT’s publishing company Wisdom, who had known Lama Yeshe for ten years. ‘Every time I’ve seen Lama Osel recently he’s said something awful to me. And he’s absolutely spot on, every time. I’m not trying to be romantic, but it’s as though he is Lama Yeshe and he is teaching me. It started when he was about four and we were out to lunch and he said in front of everyone, ‘You talk too fast, you eat too fast; you walk too fast, you do everything too fast.’ He said it with complete clarity. He knew exactly what he was saying. In the past eighteen months I have learnt more about my own speedy, berserk nature and the harm it does to others from Lama Osel than I have in my whole life.

‘I have always known it, but until now I have never paid deep attention to it. I walk into his room and already I’m nervous because I know that, like Lama Yeshe, he’s always catching me out. He says, “Why are you nervous?” It sounds so silly, but I know that I listen to what he says, not like [I would to words from] an ordinary child. He calls me Ani Nervous. All I can tell you is that it doesn’t make me angry, like it would with any other child. He has helped me see myself more clearly than any other person. It can be very painful at times,’ she admitted.