- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

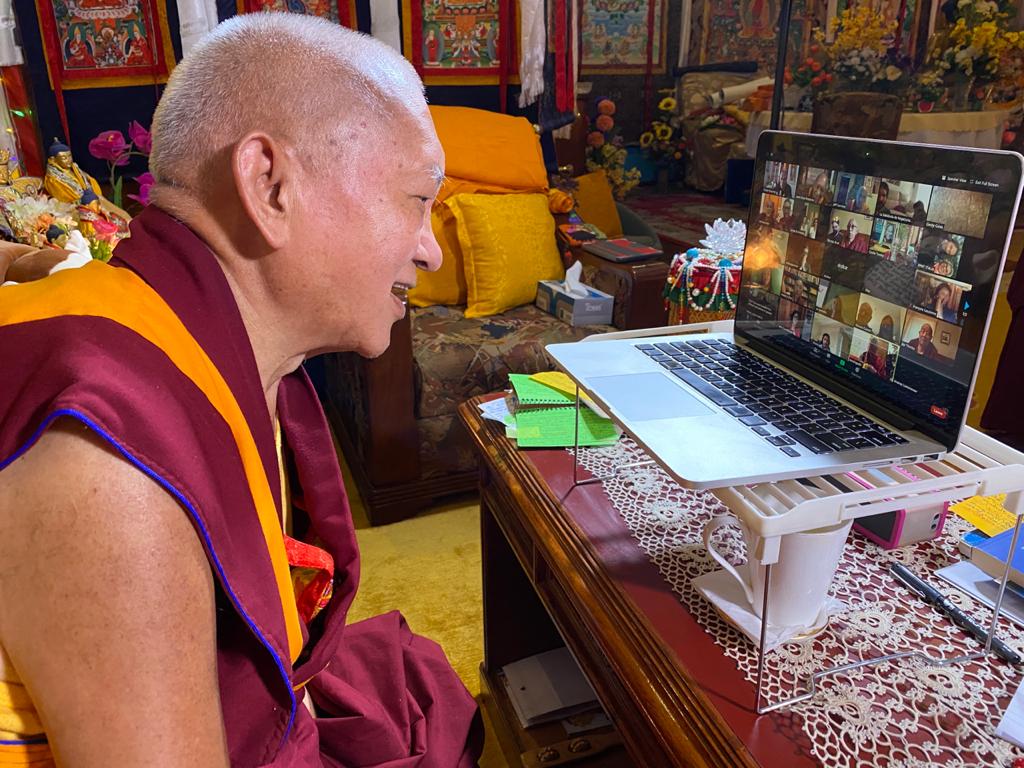

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

Superficial observation of the sense world might lead you to believe that people’s problems are different, but if you check more deeply, you will see that fundamentally, they are the same. What makes people’s problems appear unique is their different interpretation of their experiences.

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

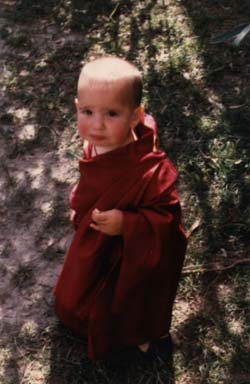

Reincarnation: The Boy Lama – The Birth

by Vicki Mackenzie

Outside, the heavens opened. Maria, the mother, lying with her newborn child, was scared. Lightning flashed, the rains poured down, filling the streets with so much water that they looked like a river in full flood. This was the first time she had been alone at a birth. Her four other children had been born at home, which was how she liked it, but for some strange reason she had been advised by a Tibetan lama to have her fifth child amid the gleaming technology of a modern hospital. In spite of all the apparatus and the cold formality of the hospital ward, the birth had been ridiculously easy. Just one contraction and the baby had been there. Now she was alone waiting for her husband, Paco, to come. When he arrived, he took one look at his son and said with some awe, “He’s so serene, his face is full of light.” Maria suggested he find a name for him. When he returned the next morning, he said he was to be called ‘Osel,’ which means ‘clear light’ in Tibetan.

This was the child who was destined to become one of the most unusual spiritual leaders of his time. For Osel Hita Torres was soon to be officially recognized by the Dalai Lama himself as the reincarnation of Lama Thubten Yeshe, who had passed away in California eleven months earlier. It was later said that it was typical of Lama to engineer both an archetypal Western death and an archetypal Western birth–just for the experience.

From the moment they took Osel home to their small house, which had been built by Paco himself in the simple, charming village of Bubión, high in the Alpujarra mountains, Maria noticed that he was not like her other children. He never cried. When she forgot to feed him because she was busy with her other children, she’d race upstairs to find him lying in his cot wide awake, looking and waiting. He let her sleep all through the night, every night, from the day he was born. It was as though his entry into the world was not intended to cause inconvenience or trouble to the family in any way.

In fact, from the time he was born, Osel seemed to bring them luck. For the previous six years, life had been tough for Paco and Maria–with so many mouths to feed and money extremely scarce. They were badly in debt, and the strain was beginning to tell. Theirs was a good marriage, but the relationship was beginning to crack under the strain. Now a new hotel was to be built in Bubión, and Paco found work as a builder. He worked all hours, and the money came in fast. Soon they were able to add more badly needed rooms to their cramped house. The strain lifted. Life suddenly began to improve. For a baby who hadn’t been planned for, Osel wasn’t doing too badly. But this unpretentious, hard-working Spanish couple had no idea of the galvanic changes their newborn son was about to bring to their lives.

Paco and Maria had met on the island of Ibiza in 1976. Paco, a shy, self-effacing man with a gentle, kind face and piercing blue eyes, came from a poor family and had left school at the age of nine to work in a factory. Later, seeking something more from life, he had thrown in his job, gone to Ibiza, and met François Camus, a Frenchman who had met Lama Yeshe and Tibetan Buddhism on his travels in the East. Paco listened to what François had to tell him, intrigued at first, then deeply interested. Maria, dark-haired, dark-eyed, vivacious, and extremely attractive, had taken a week off from her job buying and selling stamps to come for a holiday in Ibiza. She met Paco and François and never went home. Middle-class and convent-educated, she had no particular interest in Buddhism, but she certainly liked the people who practiced it. “They were so calm and peaceful, good to be around,” she said. In particular, she liked Paco. Their relationship was soon established.

Their easygoing island existence lost much of its appeal when Lama Yeshe arrived in 1977 to teach a two-week course there. Maria had never met anyone like him. “We’d had some teachings from other more traditional lamas who had come with Lama Yeshe, and although I had an open mind, I thought all the adoration, the prostrations before them, a bit too much. Then Lama Yeshe came. More than twice the number of people turned up to see him–the excitement level was very high. He came in smiling at everyone, looking so kind. Then he started to laugh. He kept on laughing, laughing.

“I’d never seen anyone like him. His energy, the power coming out of him, was incredible. He was transmitting with his face, his hands, his whole body–every way he could to make us understand. I didn’t understand a word that he said, but something happened inside me. I can’t describe the feeling, but it was very strong. Spontaneously, I put my hands together. I knew this was a man I could dedicate my life to,” she said.

And so Maria, Paco, and François approached Lama Yeshe with the idea of starting a retreat center on mainland Spain. Lama listened to their plans and agreed. Ibiza was good for initiating interest in Buddhism, but somewhere more ‘serious’ was needed to consolidate the practice. Lama contributed his own suggestion–the retreat center should be open to people of all religions who wanted time, space, and peace to develop their interior life. After a long, arduous search they finally found the right spot, a plot of land on top of Spain’s highest mountain, Mulhacén, 11,407 feet above sea level in the Alpujarra mountains, south of Granada. The air was pure, the view sensational, there was no noise, no disturbance from human or machine. It was also totally remote and inaccessible. For six years, Paco and François put all their energy and money into making it habitable, building not only the retreat cabins and meditation house but also the road leading to it–by hand. It was a Herculean task, a creation inspired by their devotion.

Their efforts were rewarded by the sudden unsolicited arrival of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who went first to Bubión, where he made a point of meeting the local priest and celebrating Mass with him, and then to the retreat center which he named Osel-Ling (‘Place of Clear Light’), meaning the clear light of the purest, most subtle mind, the final goal of meditation. No one was quite sure what had prompted the Dalai Lama to make this curious detour from his busy European tour to visit a remote Buddhist outpost run by keen, but utterly unimportant Buddhist students. Later, when Paco, inspired by the light he had seen in his son’s face, came up with the name Osel, Maria initially hesitated. It seemed pretentious, too much to live up to. Here François stepped in. “You have put so much into the center, it’s right that the center should now be part of you,” he reasoned. Maria relented.

While Paco had physically made the center she had physically made the children, living across the mountain in Bubión where amenities were more suitable for bringing up babies. Her union with Paco had been remarkably fertile, much to her own alarm. She had never wanted children, her maternal instinct not being at all strong and her desire for independence enormous. She complained loudly to Lama Yeshe–bemoaning the fact that she wasn’t free to engage in long spiritual retreats like her unattached friends. “Your children are your retreat,” he answered. “You should relate to each one of them as though they are a buddha, because you never know who they are. Even if they are not buddha, it is good for your mind to think like that. Besides, it is true that everyone has the potential to become buddha, and so it is good for the children for you to treat them that way,” he told her.

Nevertheless, when Osel was conceived, she was furious. She had four children under six: Yeshe, five years old; Harmonia, four; Lobsang, two; and Dolma, only five months. She was alone most of the time with the children (Paco being busy at the center) in an overcrowded small house, with no help and large financial worries. A new child was just what she didn’t want. Ironically, a few weeks previously Paco had tried to persuade her to have an IUD fitted–the other methods of contraception having singularly failed–but the idea had been repugnant to her. She’d been to the doctor but had come away knowing she could not go through with it. Lama Yeshe had just died, and Maria, trying to think of some way to appease Paco, said to him, “Well, maybe Lama Yeshe is looking for a mother.” Paco was not convinced. Three weeks later, she discovered that she was pregnant yet again (in spite of their usual contraceptive methods), and as she ranted at Paco, he acidly threw her joke back at her. “Maybe it’s Lama,” he sarcastically retorted.

The thought that maybe it could be Lama inside her was, however, the only thing that kept Maria from total despair. “It was a fantasy, the only thing that gave me energy to cope. I never believed it for a second,” she said.

At this point, all the FPMT centers around the world got a letter from Lama Zopa saying there was no need for the students to continue to pray for the quick return of Lama Yeshe since a woman was already pregnant with him. Maria and Paco received the news with mixed feelings. On the one hand, they were delighted at the thought that they might see their beloved Lama again. On the other, they were naturally dubious about the whole issue of reincarnation. They had the intellectual knowledge, like so many of us, but no personal experience. On balance they considered this a golden opportunity to see how it worked. They didn’t realize how close they were going to get.

Maria had well and truly dropped her fantasy about Osel being Lama Yeshe after he was born. She was far too busy with all her domestic chores to indulge in such daydreams. She did notice, however, that Osel continued to be a ‘different’ child. He didn’t seem to need to be with her, or his siblings. He was very self-contained, almost meditative, and could spend long hours contemplating unlikely things. “He used to hold and look at subtle things, like a single hair, for a long time. Most children don’t have the physical ability, nor the interest in such things,” mused Maria. “He had strong powers of concentration, too.

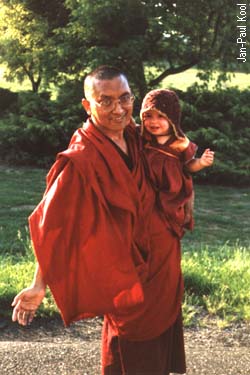

When Osel was five months old, Paco and Maria took him to Switzerland in a small basket for the Kalachakra initiation being given by the Dalai Lama. Later, they all went to Germany to attend the FPMT meetings, now being presided over by Lama Zopa, who had succeeded Lama Yeshe as head of this rapidly growing organization. When Lama Zopa spotted the baby, he asked his name, and when told, “Osel, from Osel-Ling,” he burst out laughing. Later, during a ceremony he was giving, he cryptically remarked, “Lama is very close to us at this moment. He might even be in the room with us.” Maria spotted a pregnant woman in the audience and wondered. Or was Lama Zopa referring to the spiritual presence of Lama Yeshe which was close at this time! No one thought he was talking about the little figure in the basket.

Two months later, Lama Zopa came to Osel-Ling to give a course. During a tea-break Maria left the meditation room, and on her return found, somewhat to her astonishment, that Lama Zopa had lifted Osel on to the throne with him, and her child was busy playing with the dorje and bell–ritual implements used by Tibetan lamas. That lunchtime, Lama Zopa summoned Maria to him and questioned her thoroughly about Osel’s conception and several other issues. He didn’t pass any comment. Instead, just before he left, he held a long-life ceremony for Osel, explaining to the parents: “Osel is a very special child. He has the karma to benefit many, many sentient beings in this life. Thousands maybe. Look after him well. Don’t put him in any polluted place. Don’t let people smoke near him. Take great, great care of him.” Then, he gave Maria Lama Yeshe’s mala (rosary), the one he’d had with him when he died. Maria was nervous. Had she influenced Lama Zopa in some way by her crazy fantasies while she was pregnant! Had Lama Zopa somehow picked up on her thoughts and been subconsciously directed by them!

But then life proceeded in its domestic humdrum way, and Maria, surrounded by five small children, pushed the things Lama Zopa had said to the back of her mind.

Reincarnation: The Boy Lama – The Search

by Vicki Mackenzie

In accordance with Tibetan tradition, which has its own precise procedure for tracking down reincarnated lamas, he’d consulted various oracles. There had been a variety of pointers. One had indicated a Western child born to a couple of Lama Yeshe’s students living in Kopan itself. Another had actually predicted that the child would be born in Osel-Ling and that the mother’s name was Maria, or the Tibetan equivalent. And a clairvoyant nun, a student of Lama Zopa’s, had looked in a mirror and come up with the name Paco and seen the profile of the mother. At the time, it had meant nothing to her. Lama Zopa took note, but not too much notice. He said oracles were not always reliable and much stronger proof was required in this case.

He paid attention to his dreams. One poignantly vivid dream revealed Lama Yeshe declaring that he was about to take another human form. He’d heard the cries of his students calling out to him in need and suffering and could no longer stay in the realm of bliss, ignoring their plight. A later dream showed Lama as a small child with bright, penetrating eyes, crawling on the floor of a meditation room. He was male and a Westerner.

So Lama Zopa, in his new role as successor to Lama Yeshe and head of the rapidly growing FPMT, traveled around the world visiting the various centers, giving teachings, guiding meditations, bestowing initiations–and keeping a watchful eye for any baby who, to his clairvoyant mind, was in any way ‘special.’

When Lama Zopa came to Osel-Ling in the autumn of 1985, he saw Osel crawling on the gompa floor. He had clear far-seeing eyes. He was a Westerner. His face was exactly the same as the child in his dream. Lama Zopa sat up. He brought Osel onto the throne with him to have a closer look. Yes, it was definitely the child of his dream. He noted the child’s familiarity and liking for the dorje and bell. That could have been a coincidence. More subtly he recognized that Osel was leaning against him in a manner similar to the way Lama Yeshe had done when he was paralyzed with a stroke in California just before he died. He also watched the way Osel rubbed his head round and round, a habit Lama Yeshe had always had.

Interested, he called Maria to him. When had Osel been conceived? Maria thought back. It was the exact date when Lama Zopa had had his first dream of Lama Yeshe announcing he was going to be reborn. He asked Maria if she had had any notable dreams during that time. She replied that one had, in fact, stuck in her mind. She had been in a large cathedral where Lama Yeshe was giving teachings to a huge crowd. Many were Christians, and they were all kneeling rather than sitting cross-legged on the floor. With everyone else, she went up to Lama to receive his blessing, and when he touched her, she felt as though water, blissful golden-white water, was pouring through her, purifying her. Lama Zopa made no comment.

He asked when was the last time she had seen Lama Yeshe and whether he had said anything significant to her. Maria remembered the occasion well. It was a full year before he died, in February 1383. Lama had come to Spain, and she, Paco, and François had gone to him with practical questions about running the retreat center. He had given them advice on nothing else except Osel-Ling, as this was all they had talked about. But Lama Zopa could hear for himself what had been said, since they had videotaped the meeting for future reference. Lama Zopa replied that he’d very much like to see it.

Watching the video, he was struck by some fairly incongruous remarks Lama Yeshe had made in the context of giving practical advice. At one point, he had said, “Osel-Ling is such a beautiful place. It reminds me very much of the Himalayas. At some point in the future, I’d like to spend a lot of time there.” More significantly he’d remarked to Maria and Pace, “I know how much you have done for the center, how dedicated you have been. I shall never forget you. Even if I die, I will never forget you. We have much business, much karma business between us.” At the time, the words had meant nothing to Maria and Paco, and they had promptly forgotten them. Now Lama Zopa began to glean their true meaning.

In fact, Maria and Paco were ideal candidates for the job of parenting a reincarnated Tibetan lama–with all the demands and controversy it would inevitably bring. They were both down-to-earth, no-nonsense, stable, hardworking, honest people. They already had a large family, and so a fifth child who would be separated from them for long periods of time would not be the same wrench as if it were their only child. More importantly, Maria was not a clinging mother. Quite the opposite. While she was conscientious in looking after her children, she could quite happily let them go. Maria had openly stated to Lama Yeshe several times that she did not need children to fulfill her life. It was an ideal quality for the mother of a son who needed to get on with his mission in life, unhampered by maternal possessiveness. And then there was Paco–steady, strong, gentle, utterly devoted to the Buddhist path, and with a natural affinity for children, a quality that was to come in very useful.

The case for Osel Hita Torres was growing. At this point, Lama Zopa wrote to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who all this time had been doing his own prayers and observations for the rebirth of Lama Yeshe, with a list of possible candidates whom Lama Zopa had observed, all of whom showed favorable signs. There were ten children in all, including, amongst others, three Tibetans from Nepal; two children from Tibet who were born near the area where Lama Yeshe’s family lived; and two Western children, one with an Indian father and a Western mother. After a while, the Dalai Lama replied that he had meditated on the names, and one of them definitely was Lama Yeshe’s reincarnation, but he wanted more time to make sure. Two months later, the Dalai Lama contacted Lama Zopa again and said that the name that repeatedly came up was Osel’s. The evidence now seemed conclusive. Lama Zopa’s own convictions had been ratified by the person whom he, and 14 million other Buddhists, consider to be the most holy being on earth, a living buddha, His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

The call came at breakfast time on 18 April 1986. Maria, surrounded by the chaos and noise of her large family squabbling over the cereal packets, could hardly hear the soft voice of Lama Zopa calling from India. Would she please come to Delhi next week and bring Osel with her for some tests? The money could be acquired from the resident geshe at the retreat center who happened to be holding on to the exact amount for some unspecified purpose. Maria could hardly take it in. What was Lama Zopa intimating? Was Osel going to be tested along with other children to see if he was, after all, Lama Yeshe! With her mind in a complete whirl in the rush to get ready, she hardly had rime to think about the ramifications of her journey.

Their arrival in Delhi hardly seemed auspicious. The pre-monsoon heat was suffocating, and Osel, used to the fresh, spring air of the high Spanish mountains, began to wane visibly. And he was jetlagged into the bargain. The quarters they were living in were crowded. He got horribly bitten by mosquitoes, and then he fell down, cutting his eye.

Maria didn’t feel too good either. She was anxious about what was happening (still harboring guilt feelings about the part her subconscious thoughts might have played in the matter) and her fourteen-month-old son was fractious. Then she was told that the reason they had come to Delhi was that the Dalai Lama was there and wanted to see Osel before he went overseas. They got ready: Lama Zopa, his secretary, Jacie Keeley; Yeshe Khadro, the Australian nun, Maria, and Osel. Bouquets of flowers were bought (Yeshe Khadro purchased a solitary white rose for Osel to give) together with traditional white scarves by way of offerings.

Still nothing definite had been said. Instead, Lama Zopa announced that they were all going to get into cars and drive some 250 miles to Dharamsala. They drove for fifteen hours nonstop, Osel becoming increasingly testy. Maria had no idea what was going on. Unbeknown to her, the Dalai Lama had counseled Lama Zopa that announcing Osel’s identity at this stage might be courting problems. Fourteen months was an exceptionally young age at which to recognize a reincarnated lama, most tulkus being officially instated at four or five years old. Lama Zopa was in a dilemma. Nothing on earth would induce him to bring trouble to his beloved Lama’s life, yet he knew how badly his Western students needed not only the proof of reincarnation, but the living presence of Lama Yeshe in their midst once more. On that long car journey to Dharamsala, he was meditating on the right course of action.

When they arrived, his mind was made up. He called several of Lama Yeshe’s students, monks and nuns who were studying or retreating at Tushita Retreat Center, dressed Osel in one of his own yellow shirts, placed him on Lama Yeshe’s throne in Lama Yeshe’s room, did three prostrations before him, and made a mandala offering to him. “Here is your guru,” he said.

With that, Osel, who until then had been beyond exhaustion, flopped back against the cushions, threw aside his bottle, suddenly fired with energy. His whole demeanor changed. He sat bolt upright, wide awake, eyes shining, his face full of vitality He picked up the dorje and bell in his small hands, the correct hands, and with tremendous gusto waved them in the air as a Tibetan lama should. He put them down and repeated the action again, and again. Seven or eight times. And all the time laughing, laughing. People began to cry. It was so like Lama. He had come back to them. Maria felt paralyzed inside. Finally, she understood. The child she had carried and borne was being hailed as the reincarnation of the great Lama Yeshe–the man who had shown such extraordinary skill and dedication in guiding Westerners to enlightenment. How could this be?

Later, she spoke to Lama Zopa. Why hadn’t he warned her beforehand? He replied he had to be completely sure and then asked if she believed. “I don’t know. It’s difficult. I think I want more proof,” she answered honestly.

More proof was forthcoming. Osel still had to undertake the traditional tests, given to all reincarnate lamas. And so, as Tibetans have done for hundreds of years, Lama Zopa collected some of Lama Yeshe’s possessions; he mixed them with others of similar type and asked Osel to pick out those that were rightfully his. Starting with a mala (rosary), a fairly ordinary one made of wooden beads that had been a favorite of Lama’s, he placed it on a low table along with four others almost identical in style and one made out of bright crystal beads intended as a natural red herring for a baby of fourteen months.

Then, with Maria and a few Western disciples as witnesses, he requested Osel, “Give me your mala from your past life.” Osel turned his head away as if bored. Then he whipped it back again and without hesitation went straight for the correct mala, which he grabbed with both hands, raising it above his head, grinning, in a triumphant victory salute. An Australian monk, Max Redlich, was ready with two cameras, a brand-new one and an antique device belonging to Lama Yeshe. “Use the old one,” charged Lama Zopa. Max ignored him, reaching for the sophisticated camera instead. It jammed. Max missed the shot.

After a break, Lama Zopa set up the bells–there were eight of them. This time Osel dallied. He picked up the bells in pairs, ringing them and setting them down. Lama Zopa instructed again, “Give me your bell from your past life.” Maria, watching the spectacle, never believed her child could perform the same miracle twice. He was so young. Such a feat must surely be beyond him. Osel continued to play with all the bells, picking them up and putting them down again. To the onlookers it looked as if he were teasing them all. Lama Zopa repeated the instruction. “Osel, give me your bell.” Osel delicately, but with great determination, picked up Lama Zopa’s hand and put it on the correct bell. This time Max was ready with the functioning camera.

Osel had passed the tests and could now be formally recognized as the legitimate incarnation of the late Lama Thubten Yeshe. The Western monks, nuns, and disciples in Dharamsala, who had all been intimately acquainted with Lama Yeshe, could not take their eyes off the fair-haired toddler running in their midst in diapers. Here again, they were told, was their great guru–but in such a different form. For most, it was hard to accept totally. They watched, looking for yet more signs. Osel gave them.

At the top of the mountain above Tushita Retreat Center is the house where the great Kyabje Ling Rinpoche, senior tutor to the Dalai Lama, and Ninety-seventh Throneholder of Je Tsong Khapa, once lived. He had passed away in December 1983, and in tribute to this eminent scholar and spiritual master, the Dalai Lama had decreed that his body be preserved according to the ancient Tibetan method. It exists to this day, placed in the drawing room of this rather unremarkable colonial house, sitting in the lotus position, the hands in the mudras (symbolic gestures) of giving teachings and with a look of utter serenity on the ancient, wise, and consummately compassionate face.

Osel was taken up there with Maria and Max Redlich. When he saw the figure, he threw himself on the ground in a full prostration. He got up and did it again. Three times. Maria and Max were astonished. Where had he learned such things! There was more to come. Later, he came across the stupa dedicated to his former root guru, Trijang Rinpoche. Without prompting, Osel set off at a trot around the stupa, circumambulating it in a clockwise direction as every good Tibetan pilgrim should. He stopped occasionally to do prostrations, and to make sure that the others were following and doing likewise. For a fourteen-month-old child his behavior was extraordinary, to say the least.

Perhaps the most touching scene of all was when Osel was taken to meet the reincarnation of Trijang Rinpoche, a four-year-old with a commanding presence and a wisdom far beyond his years, who was already receiving hundreds of Tibetans for blessing. Lama Yeshe had Seen devoted to his great teacher and had wept openly when he died, saying that everything he had been able to do had come from the kindness ofTrijang Rinpoche. Now Osel was told whom he was going to meet. The child could hardly contain himself–his whole body shook with excitement. Bearing gifts, they drove to the new Trijang Rinpoche’s house–Osel still quivering with anticipation–and there, the two tiny figures met, beaming at each other with obvious delight. Osel then reached for some money that was meant as an offering and with great joy handed it over to Trijang Rinpoche who, with equal delight, handed it back again. This exchange went on for several minutes, the two participants clearly enjoying their game enormously. When Osel left, he was walking on tiptoe, his feet hardly touching the ground.

Those who were witness to Osel’s behavior watched in wonder. They talked among themselves, musing on the strangeness of this small child who had suddenly come among them. Word rapidly spread about the extraordinary phenomenon of the baby Spanish lama

Reincarnation: The Boy Lama – The Enthronement

by Vicki Mackenzie

The next time I saw Osel was in the middle of March 1387 on the occasion of his enthronement. The enthronement had originally been planned to take place in Kopan, and after not too much deliberation, the thought of seeing Lama Yeshe’s reincarnation once again installed in his headquarters was sufficiently enticing to overcome misgivings about the extravagance of flying so far for just one event.

I arrived in Kathmandu and for the first time headed not for the monastery on the hill but for the relative luxury of a small new hotel in among the winding alleyways of Thamel, the colorful bazaar area of Kathmandu. Having showered and changed, I eagerly telephoned the FPMT Central Office for final details of the enthronement. The embarrassed tones at the other end immediately indicated that something was badly wrong. After a lot of discussion, it emerged that it wasn’t definite that the enthronement was going to be held at Kopan. In fact, it wasn’t definite that the enthronement was going to happen at all. At the moment, Osel was in Dharamsala with his family, and Lama Zopa was sorting out what was best for everyone. I was rendered speechless by this bombshell. I’d come so far, spent so much money, and even had a commission from a German magazine to cover the event, just to be met with what appeared to be typical Eastern inefficiency and vagueness.

For the next week, I and many other people, including several journalists who’d flown in from across the world to witness the event, were kept in suspense. One minute it was announced that the enthronement was going to be held in Dharamsala, the next that Osel was coming to Kopan. The tension was excruciating. I became increasingly exasperated and upset, and when I eventually met Lama Zopa on the path outside the gompa one afternoon in Kopan, I complained. He laughed. “It will all make for a richer experience,”‘ he said cryptically. Unbeknown to me, the dilemma was not caused by some capricious whim on the part of Lama Zopa but by visa complications for Osel (which were later sorted out). After a few more days of shifting venue–during which time we were mollified by some wonderful teachings given by Lama Zopa–it was finally announced that the enthronement was definitely on, in Dharamsala.

Panic! We rushed to various travel agents and the Indian visa offices, our hearts in our mouths in case we didn’t make it to Dharamsala in time. It was a long, complicated journey, across India and north through the turbulent Punjab into the very topmost peak of the subcontinent. To make matters worse, it was Holi week, one of the largest religious festivals in India, and it seemed that every seat on plane and train had been booked up weeks before. Every day, we dashed over to the travel agents to see if there were cancellations, and at the eleventh hour I miraculously got on a plane to Delhi. The cost of this trip, along with my anxiety, was rapidly mounting. There were two days before the ceremony was planned to begin.

After a few hours’ sleep in the bustling, noisy capital, I rushed through the streets to Old Delhi station to try to get a seat on a train that would take me and my traveling companions to Pathankot, the nearest railway station to Dharamsala. Stepping over countless sleeping bodies who seemed to have taken up permanent residence in the station, I made my way to the reservation office, which already had a sizeable crowd waiting outside for the doors to open. During Holi week all the mighty millions of India were obviously on the move. When the doors were finally unbolted, we surged forward as one. In the mêlée I was somehow pushed to one desk, where a patient railway clerk consulted a timetable which looked as complicated as a computer manual, and much to my astonishment offered us the last remaining six seats in a train leaving that night–just enough for me and my traveling companions. It was a sleeper–third class, non-air-conditioned.

Returning that night with my fellow travelers to the unbelievable chaos of Old Delhi station, I clambered aboard the filthiest train I’d ever seen and discovered to my horror that our ‘sleeping’ compartment consisted of wooden seats that converted into beds. It also had no door and, in fact, no division from the countless other bodies all crammed like cattle into the corridor. Attachment to an inner-spring mattress once again rose in my mind. I was now finally beginning to believe the fundamental Buddhist tenet that attachment, any attachment, only causes suffering. Through the night we trundled along in enforced intimacy with Indian humanity (who in the way of their race accepted all life’s conditions with uncomplaining passivity), the journey broken by frequent stops and a constant- stream of food vendors offering their wares in vessels that hadn’t seen dishwashing liquid for the best part of a year.

The lavatory was another experience–a fetid enclosure where you balanced your feet on either side of a gaping hole, watching the railway tracks swinging perilously beneath. At least I didn’t have Delhi belly. Instead, I’d come down with the flu. I was hot, and my nose was running like a Delhi railway porter. Memories of those romantic films and travel documentaries extolling the mysteries of going by train through the Indian countryside flashed before my eyes. Were we in the same country!

At 10 the next morning I stepped out at Pathankot station, my red nose coordinating nicely with my eyes. After a ‘safe’ breakfast of boiled eggs in the restaurant at this friendly station, with bougainvillea climbing the pillars and orange-sellers on the platforms, we piled into two taxis and negotiated the fare for the four- hour drive up the mountain to Dharamsala. Inevitably, one car broke down and the other ran out of oil, as is the way with Indian taxis, but since we were traveling in tandem, we came to each other’s rescue, and I was by now resigned to the traumas of travel on the subcontinent. At last we drove past the little English church where Lord Elgin is buried, and entered a world of little Tibet. Here, the thousands of Tibetans who followed their leader into exile, choosing to become refugees rather than suffer under Chinese rule, have over the past twenty-five years resurrected their own culture with considerable success.

With the Dalai Lama’s residence as its spiritual centerpiece (a modest bungalow contrasting starkly with the mighty Potala Palace where he once lived), Dharamsala now boasts a large, golden-roofed temple, housing a giant statue of Chenrezig, the Buddha of Compassion (with His thousand arms reaching out to help all sentient beings), of whom His Holiness is said to be an emanation. There are several thriving monasteries, where monks of the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism continue to keep alive their rich spiritual heritage of learning, debate, and meditation. Down the hill, the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA) houses many priceless ancient texts that were smuggled out of Tibet and were thus rescued from the atrocities of the Chinese invasion; nearby is the Tibetan Medical Institute, now headed by Dr. Tenzin Choedak. Dr. Choedak is the Dalai Lama’s personal physician and was recently released after twenty years’ imprisonment and torture by the Chinese for unspecified ‘crimes.’ He is now busily engaged in preserving the ancient science of Tibetan medicine. Dharamsala also has a school of arts and drama and a thriving crafts industry where carpets and artifacts are made and sold.

It was good to be here again. The air was pure, and the view of the plains below and range upon range of snow-capped Himalayas behind was breathtaking. But the best thing of all was that we had arrived in time. The enthronement was to take place at the Tushita Retreat Center the next afternoon.

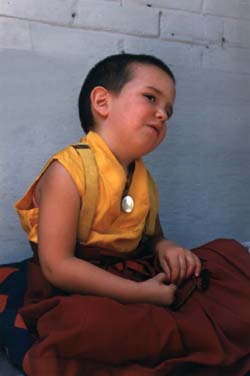

At the appointed hour, we all solemnly filed into the main meditation room of Tushita, wondering what was in store. There were about sixty of us in all, a motley crew, comprising monks, nuns, former students of Lama Yeshe, and a large press corps representing some of the most influential newspapers, magazines, and press agencies in the world. All had trekked up the steep mountain road to witness and record an event which was by anyone’s standards big news–the investiture of the world’s smallest and most unusual lama ever. Osel Hita Torres, aged two years and one month, was about to make his official world debut.

The gompa had been specially festooned for the occasion. Richly colored tangkas (Tibetan scroll paintings), depicting aspects of the Buddha, covered every inch of the walls. The throne, three feet high, was draped with bright brocades. On the floor on either side of the central aisle sat two rows of Tibetan lamas in full ceremonial regalia. Behind them sat the Western monks and nuns, and in whatever space was left sat the rest of us.

Long horns boomed, cymbals clashed, drums and damarus sounded, conch shells trumpeted in the eerie and evocative ritual of dispelling evil forces and summoning the buddhas and protectors of the ten directions. And as the lamas began their massed chorus of deep-throated mantra–that sound which reaches far beyond ordinary emotion and thus touches the very inner core of your being–Osel arrived, carried in his father’s arms.

I, for one, wasn’t prepared for what I saw. Osel was dressed in full coronation regalia. He wore ceremonial lama’s robes and on his head was the high, crested, yellow pandit hat, the badge of office. perhaps it was because he looked so little under that grand yellow hat, or maybe it was the silence that fell on all of us as he entered, but the moment was undeniably moving. I noticed as he went past that he was sucking a sweet and under his arm he carried a fluffy clockwork owl–a reminder that he was, after all, hardly more than a baby. He nodded to the posse of photographers gathered in one corner, like one who is used to dealing with the press, and after a second of protest allowed Pace to seat him on the throne.

There he perched, a tiny figure, the focus of all the attention, with his big hat endearingly slipping over his eyes from time to time and his owl rocking incongruously to and fro beside him. At his feet to his right sat his closest disciple, Lama Zopa, his face solemn with the import of the occasion. Beside the throne sat his parents, looking both proud and anxious. Staging a public ceremony with a two-year-old as its centerpiece was for them not only nerve-wracking but fraught with potential disasters.

They had no cause for worry. For the next three hours, Osel sat on his throne watching the proceedings with a stillness, composure, and majesty that went far beyond his years. Two or three times he clambered down from his throne, once to sit on Pace’s knee for a minute, then to play with a small Italian boy he’d spotted in the congregation; but he didn’t object when Pace or his monk attendant gently replaced him on his seat. More surprisingly, he handled the photographers, who were flashing their cameras throughout the entire three hours, with consummate ease. Occasionally when he thought they were getting greedy, he’d hold out a commanding hand and say “No,” but for the most part he was astonishingly accommodating, at times even posing for them. They, for their part, were beyond themselves with glee. Children and animals win any reader, and this child was a natural. They couldn’t go wrong.

For those who understood the subtler points of Buddhism, the event took on deeper significance when they realized that here was Lama Yeshe’s reincarnation, sitting on his former throne, in his former house, sleeping in his former bed, walking round the garden he had planted, and using the same religious implements. To the believers, Osel was not just a novelty, a Spanish child being hailed as a lama, but the living proof of the continuity of individual consciousness. Here before us once again was the mindstream of Lama Yeshe, albeit in another form, returned to this earth through his great compassion to help us all on our way to the truth. To compound the miracle, he had been recognized. How many saints, I wondered, had come amongst us quietly, their works and worth unsung until, perhaps, the moment they died! And that was fine, but somehow it did not give people the opportunity to take full advantage of their hallowed presence–to learn and perceive as much as they could.

Yet, how fraught with danger was the position that Osel was now in. In publicly proclaiming his identity, the Dalai Lama and Lama Zopa had exposed him to possible ridicule, controversy, and even hostility from anyone who chose to attack him. How vulnerable he was. And how brave of His Holiness and Lama Zopa to stick their necks out in such a fashion-they must have been absolutely sure of what they were doing.

Right now Osel was handling himself and the situation as though he had indeed been born to it. He sat, dignified, on his throne while the ritual was carried on before him. He was offered Tibetan tea, which he drank with relish, and a host of other symbolic gifts: a gold-plated dharmachakra (wheel of the Dharma), symbolizing the request for the guru always to give teachings; the Kangyur and Tengyur (the 108 and 225 volumes, respectively, of the teachings of the Buddha and their commentaries); statues of Amitayus and Namgyalma (buddhas of long life); the robes and pandit hat of a Tibetan lama; and the dresses of the five dakinis, symbolizing the wisdom goddesses of the five elements (whose robes are donned by Tibetan lamas when performing their stylized, ritual dance).

The high point of the ceremony was when the lamas, led by Lama Zopa Rinpoche, lined up before him, did prostrations to him in homage, and then humbly offered the child their gifts. Without prompting, Osel took each holy gift, placed it on the crown of his head in the Tibetan manner of showing reverence, and then handed it to his attendant. That done, he placed a chubby hand on the bowed head before him in blessing. He did this again and again–through the entire ranks of the Tibetan hierarchy and then the rows of Westerners. I noticed he deviated once from this action when instead of reaching out his hand he bent forward and touched crowns with a young, handsome Tibetan lama, a mark of great respect. I later found out that this was Yangsi Rinpoche, a recognized reincarnation of a former teacher of Lama Yeshe in Sera Monastery in Tibet.

It was a staggering performance. By now Osel was clearly getting tired (although one Westerner’s gift of an ambulance with a flashing red light obviously lifted his energy for a while), but he sat through it until the end. When the last- hymns of praise had been sung, and the dedication that all the goodness accumulated be given to all sentient beings, Pace lifted him off the throne and took him out. Lama Zopa had been right. In spite of or because of the hardships and effort invested in getting there, the enthronement was a rich experience indeed.

After that mammoth performance, Osel was spent. His parents reported that he wouldn’t go into the gompa where the enthronement had taken place, let alone sit on the throne. I couldn’t say I blamed him. But a few days later, hoping for exclusive photographs for the German magazine assignment, I dared ask if Osel would be prepared to get back into his full ceremonial regalia and pose for the photographer, Robin Bath (a student of Lama Yeshe), who had flown out from England to cover the event. Much to our surprise and delight, he agreed, and we were privileged enough to receive our own private photo session.

If Osel had shone during the official enthronement, he surpassed himself for Robin’s camera. Back on the throne, he went through the gamut of Lama Yeshe’s facial expressions, all for Robin’s camera. He looked serene, holy, wise, mischievous, profound, compassionate, and funny in turn. With extreme graciousness, he took pieces of fruit from the offering bowl on the side of the throne, giving one to each person in the room–a gesture of caring and concern that was archetypally Lama Yeshe-but then to keep the proceedings from getting too pompous, he hurled an orange at Robin and burst into giggles. At another point he threw his robes over his head, just like Lama used to do, and sat there–the ultimate clown. Then he got hold of a loose-paged Tibetan text, placed it in front of him on the throne, and proceeded to ‘read’ it with the sing- song voice of a Tibetan lama, turning the pages over and placing them in a neat pile before him. It was impressive! After that he put his hands in the meditation posture, closed his eyes, and began to say mantras. It was Lama Yeshe, synthesized and in miniature.

The pictures revealed what a special moment it was, but unfortunately, the German magazine didn’t use them or the story. They were too pressurized by Osel’s story bursting into print across Europe to wait for our exclusive material. Although the press coverage overall was favorable and unbiased, inevitably, there were the journalists who lapsed into sensationalism, or did not get the facts right, and one who was downright scurrilous. An Indian newspaper said that ‘sources’ in Dharamsala had revealed that Osel had not been recognized by the Dalai Lama and that the whole story was, in part, a ruse to get funds for Kopan. This was later repudiated by Lama Zopa and the Dalai Lama himself, and the so-called ‘sources’ could not be identified. It was the only brickbat hurled at Osel. I wondered how many more he would have to face throughout his life.

- Tagged: tenzin osel hita

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.Less desire means less pain.