- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

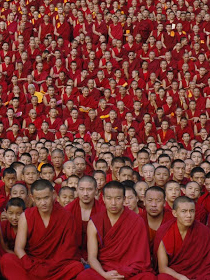

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

My approach is to expose your ego so that you can see it for what it is. Therefore, I try to provoke your ego. There’s nothing diplomatic about this tactic. We’ve been diplomatic for countless lives, always trying to avoid confrontation, never meeting our problems face to face. That’s not my style. I like to meet problems head on and that’s what I want you to do, too.

Share

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

9

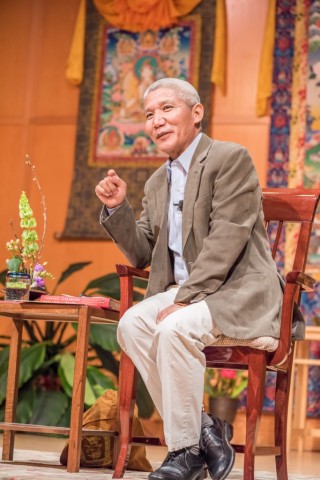

Geshe Thupten Jinpa, Portland, Oregon, US, May 2015. Photo by Chris Majors.

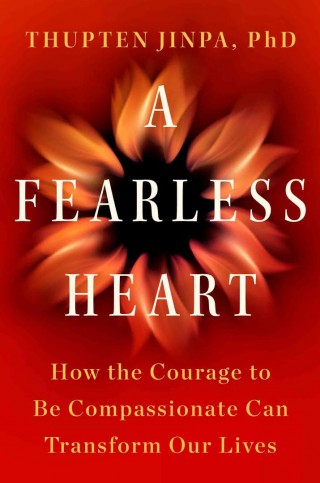

In May 2015, Geshe Thupten Jinpa, His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s principal English-language interpreter, came to Maitripa College in the United States to talk about his newest book A Fearless Heart: How the Courage to Be Compassionate Can Transform Our Lives. The book describes why compassion is important for the human species; the structure of Compassion Cultivation Training, a secular, science-based compassion program Jinpa helped develop at Stanford University; and methods for how we can act on an increased sense of compassion in the real world. Jinpa took time to talk with Mandala editor Laura Miller about the book and the development of Tibetan Buddhist practice in the West.

Laura Miller: Congratulations on your book coming out. Would you give us a synopsis?

This is, I suppose, a self-interest argument for the value of compassion. I show that numerous studies demonstrate how compassion and happiness are closely related. In fact, I refer to compassion as the best kept secret of happiness. This begs the question: if it is natural and if it is so good for us, why don’t we do it more? I bring in and discuss what hinders us from expressing our more compassionate parts – fear and pride, particularly the fear and anxiety that we bring into our relationships with others.

The second part, which is actually quite large, presents the key steps in Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT), a particular program that I helped develop at Stanford University when I was a visiting scholar, which has now been delivered and offered to so many people. We have trained and certified over 100 instructors formally. It has now been used as an intervention program to help treat veterans suffering from PTSD, and there is a private healthcare group in San Diego with 20,000 employees, which has about eight people who have been trained in CCT who are now offering this as part of human resources.

I present the key steps of these CCT practices, but also place each of them within a larger psychological context, which combines both classical Buddhist psychology as well as contemporary neuroscience and contemporary psychology. For example, for the intention setting practice, that chapter has a whole discussion of how we understand intention. What is the relationship between intention and motivation? What is the latest scientific theory on motivation and how does that relate to our perception of the world?

The final part of the book is about how all of this translates into our individual, everyday life. What does it mean to live a compassionate life on a day-to-day basis? I make the point that through cultivation we can transform compassion from a natural response triggered by a situation in front of us, to a more proactive standpoint from which we can relate to the world, a mental perspective. And then ultimately, one of the highest developments is when compassion becomes so natural that it moves from mental perspective and becomes a way of being. I actually have a short section in the book presenting the six perfections – generosity, ethics, patience, joyous perseverance, concentration and wisdom. This is, I say, the way in which the Buddhist tradition has envisioned what it means to live compassionately and behave compassionately on a day-to-day basis. Although this comes from the religious context of traditional Buddhism, the basic principles behind the six perfections have nothing religious about them.

In the final chapter, I envision how compassion will unfold in the larger world.

What has inspired you to write this book?

I have had the privilege to serve His Holiness for so long and I know that one of his main focuses is to promote an appreciation of basic human values. He calls it “secular ethics.” His Holiness is deeply interested in promoting this way of understanding and exploring human experience, and appreciating the key defining characteristics of what makes us human beings. These are qualities of compassion, empathy, forgiveness, a sense of connection, appreciation of others and so on, which are fundamental values. One of the things that His Holiness does is to convey this without any connection to Buddhism or religion. And I have been very impressed and inspired by that line of thinking and work. It has made a tremendous difference in the larger world.

I think where I see my own personal role in this area is to, in one way or another, serve as a kind of cultural interpreter between traditional Tibetan classical culture and the modern West. In my work for His Holiness as an interpreter and also in my writings and translations, I see we are now living in a very exciting world where – thanks to globalization and coming into contact with so many different cultures – we have access to knowledge and insights that were traditionally beyond what was available before. In this kind of situation I believe that when we bring the best of Buddhist traditional knowledge together with the best of the contemporary scientific approach, there can be important mutual contributions.

My own work, particularly for the Library of Tibetan Classics, was more traditional translation work. And that I think is a very important step in the transmission of knowledge and insights from one tradition to another. Most of the major epochs in cultural transformation have come from exposure to a different culture and translation work. In the case of Tibet, translation of classical Indian Buddhist texts completely reshaped the Tibetan tradition. I believe that translating many of the key classical Buddhist texts, especially Tibetan and Indian, will really shape modern sensibilities and modern value systems, including science.

I think in order for these ideas to impact contemporary culture in an effective way, there also needs to be a second-level interpretation. The second-level interpretation draws from the actual translated texts, but they are brought into the idiom and conceptual framework and the language of the host culture. When I translate texts, I am very faithful to the original because I am reproducing what existed in the original. But when I do the second-order interpretation, then my loyalty is really to the host culture, which is the English-speaking world. And in a way, this particular book, if you can call it “interpretation,” would be at this second level.

In the introduction to the book you include a quotation from His Holiness from a Mind and Life Institute meeting in India where His Holiness is urging scientists to look into the positive qualities of the human mind, like compassion, that can be cultivated through contemplative practice with the idea that with scientific understanding, some of these practices can be offered to the world as techniques to increase emotional well-being, mental well-being. So what strikes me about this quote is how insightful and far-sighted this encouragement from His Holiness was. It seems to be that His Holiness has really been a catalyzing force for this research and findings that are clearing the way for the development and spreading of secular compassion. Can you share some of your thoughts of His Holiness’ role in this and how it has influenced your work?

His Holiness said, after the establishment of the Mind and Life Institute in 1985 and the first conference in ’87, that it became very clear to him that something very important could come out of the meeting of these two investigative traditions – Buddhism and modern science. Both of them are interested in understanding the human condition. In the West, scientists focus more on the outside; in the East, the classical contemplative traditions have focused more on the inside. That is a crude way of putting it, but it is a simple way of putting it. And it makes perfect logical sense to say that if we bring the best of these approaches, then we have a complete picture. That seems to be the basic impulse on the part of His Holiness and he has been right from the beginning an enthusiastic advocate for integrating knowledge.

As these conversations unfolded, it became evident that there are so many resources in the classical Buddhist tradition, particularly when it comes to mental processes. The interesting thing about the contrast between Buddhist psychology and contemporary Western psychology is that, until recently, contemporary Western psychology didn’t really have much to say when it comes to actual mind training. They are interested in understanding the phenomenon of mind, what are its mechanisms, why do certain people behave in a particular way. The focus has been very much on what goes wrong – on the pathology – because the model is medical. His Holiness realized that the focus in the West has been just on understanding the diseases and the pathology. The method that they are bringing is very rigorous because there is a systematic approach looking at the causal dynamics and the connections and their behavioral connections and so on. But, when it comes to recommendations on what can be done, there is a kind of a paucity in the Western approach.

In traditional Buddhist psychology, however, in addition to the tremendous depth of knowledge and understanding about how the mind works, there are also a lot of practices that are recommended that individuals can do, such as practices for how to strengthen one’s compassion, how to open one’s heart; how to develop greater resilience; how to develop greater patience; how to learn to observe one’s thoughts and emotions; how to regulate one’s emotions when one gets worked up; how to develop this meta-level awareness, where one can step back and disengage and observe what is going on in the theater of one’s mind. There are so many resources there and His Holiness basically felt that it makes no sense not to connect the two. Clearly, the Western scientific side could learn from the techniques that are there in the Buddhist traditions as well the insights that are there in Buddhist psychology and science of mind.

That there could be potential offerings to the world from this connection, His Holiness has been prophetic. Look at the story of the “mindfulness movement.” Of course, there is a lot of fad surrounding this, some of which is slightly excessive. But that doesn’t preclude the fact that the mindfulness movement has truly made tremendous contributions in the clinical domain. For example, the prevention of a relapse of depression when mindfulness is added to cognitive behavioral therapy – there is tremendous data that shows its efficacy. The mindfulness movement has in some sense proven His Holiness’ intuition that the meeting of the two traditions can really be very constructive. In fact, people like Professor Richard “Richie” Davidson, who is a pioneer in what is now called “contemplative science,” when you ask them about the evolution of the emergence of contemplative science, will explicitly attribute it to His Holiness and to his remarks at that particular Mind and Life conference, where he asked scientists to use their tools to look at the positive side of the human mind and see if some of the classical techniques actually work, and then adapt and offer them to the world.

It seems that with the popularity of mindfulness, it’s opened the gates for compassion training to come in. Would you talk about that?

I think one of the advantages of mindfulness language is that it is value neutral. That is why it is much more palatable and acceptable in a culturally secular environment, especially in the United State where there is a religious, almost dogmatic insistence on the separation of church and state. Mindfulness, because the language is about attention, present moment awareness, disengagement from habitual thought patterns, observing what goes on in your experience, and becoming more aware of your own body sensations and so on, is value neutral, and the concept is not that difficult to understand. It is difficult to experience it because we do not come into the world naturally gifted with mindfulness; it is something you need to cultivate. However, the concept itself is not that difficult, and that’s why there’s much less resistance in terms of receptivity to concepts about mindfulness.

People who’ve engaged with mindfulness have the ability to naturally experience what it feels like to be in a calmer state of mind, to be in a more focused state of mind. It allows for deeper qualities of mind; you can get a taste, and that is why it much easier to understand. Something like compassion is much more complicated because compassion also has a strong emotional component. Also, historically, the word “compassion” has belonged to the value side of language and has been seen as being part of the religious value system, which creates some cultural resistance on the part of some individuals. Now it’s changing because science is increasingly showing us that compassion is an inherent part of who we are as social creatures. It has nothing to do with religion; it’s part of who we are as human beings. I think the resistance to compassion that arises from thinking that it is a religious value only is disappearing. It’s His Holiness to whom we should really give the credit because His Holiness has been saying for over 40 years across the world that compassion is a natural human quality. Although historically it may have been the religious traditions that have promoted compassion, in itself, compassion is independent of religion. He has been a very strong voice advocating that and people are beginning to listen to this.

Can you describe the work that is being done at Stanford University on compassion training?

My work at Stanford began in the winter of 2007. In 2005 there was an important conference on depression, craving and suffering, where His Holiness interacted with a group researchers and scientists at Stanford University. It was truly inspiring for a lot of researchers and clinicians who were there who had never thought something like this could potentially be of interest to the researchers in the clinical community. This led to a conversation within the core group of scientists at Stanford School of Medicine that here was something that had real potential. A neuroscientist by the name of Jim Doty, who attended the conference and is now a faculty member of Stanford, had an endowed a chair in the neurosurgery department and set aside some funds to explore the possibility of setting up a kind of a permanent center there. He invited me to be part of the founding group and once I had a conversation with him, I was convinced that there was a real potential.

At that time, although there were individual researchers doing scientific studies of compassion, it wasn’t really accepted as part of the legitimate field of scientific inquiry. One of the early works that Jim and I did was to use Stanford’s name and power to convene people from many different universities and different fields – neuroeconomists, clinical scientists, basic researchers, psychologists, child developmental psychologists, including Christian theologians and Buddhist scholars – to our first conference that looked at how we are defining compassion. That was very, very successful. In fact, one senior Stanford psychology professor, who was actually a real sceptic, came up to me on the second day and said, “I have to admit I was wrong.” They were genuinely impressed. Then we did another conference focusing on the measures of compassion. We had another one that explored the language of mental life. These were all attempts to bring people together from so many different backgrounds. People like Barbara Fredrickson, who studies loving-kindness’ effect on the vagus nerve; Kristin Neff, whose work has primarily been on self-compassion; and Paul Gilbert, who is a pioneer in developing compassion-based therapy dealing with people who have pathologically high shame, were there and so on and so forth. We had Richie Davidson, who is a pioneer in this whole area. At the last conference I attended, at Telluride and organized by Stanford, I was one of the main speakers. I was so happy because out of 50 to 60 speakers, about 80 percent of them were completely unknown to me, which means the field is opening up. Instead of feeling depressed that I didn’t know the majority of speakers, I took it as a cause for celebration because this means that now compassion is becoming mainstream.

While I was a resident visiting scholar at Stanford, I thought that there was a fantastic opportunity for me to develop a secular compassion training program, taking inspiration from MBSR (mindfulness-based stress reduction). I developed an eight-week compassion training program. Although the initial program was developed by myself and was tested out on Stanford undergraduates, it soon became clear that the program could benefit a lot from adding on other approaches coming from contemporary Western therapeutic traditions like Steven Hayes’ acceptance and commitment therapy and Marshall Rosenberg’s nonviolent communication, which has some very powerful tools, like how to distinguish between the language of observation that talks about the pure facts, and the language of judgement, where we bring in our interpretation of the situation. I think this is a powerful way of becoming more aware of how much judgement we bring into describing a situation because you do it by learning the language, which is in some ways more practical and easier than trying to imagine what to do, which is the meditation-style approach. I also spent several long weekends together with a team of local experts – Kelly McGonigal; Erica Rosenburg, an emotions researcher and student of Paul Eckman; and Margaret Cullen, who is MBSR trained and a family therapist – coming up with exercises. In the end, the final instructors’ manual that we came up with, which is the actual protocol, has a very strong interactive component. I really feel happy that I had this opportunity and space to do this.

And who is the training aimed for? Is it for anyone?

When I was developing this program I was very clear that we shouldn’t keep in mind any specific target constituencies. As much as possible, it should be a generic program that could be offered to adults. My understanding is that later on we could use this as a basis to develop special adaptations for specific needs, whether for the pain management, stress relief, or whatever. I really wanted to have a very generic program that could benefit ordinary people.

In chapter 1 of your book you include a short quote from Fred Rogers: “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’” This quote resonated for me in the days and weeks after the earthquake in Nepal. And I personally feel like it’s this ability to look for the people and to actually rejoice in the compassion that is arising that has helped me not despair for what is a sad, sad situation in Nepal. So could you share a little bit more on that and how that works?

I think that often when we are confronted with tragedy and situations where we see other fellow human beings doing horrible things to others, or when it’s a natural disaster, it is very natural for us to get fixated on what is wrong. Biologically, we are programmed to detect threat and danger, and fear is such a dominant emotion because fear is a signal when something is a threat and you need to do something about it. Because of this, we get so fixated on the negative side of things.

On the other hand, if we’re able to step back a little bit and also look at the positive side, every tragedy has some kind of silver lining. For example, you cite the current tragedy in Nepal with the earthquake. If we just get fixated on the tragedy and the problem, and as we are not physically there, we feel powerless and also we feel depressed. Yes, the perception of the suffering is very important because that is what is going to pull our heartstrings, which is what is going to motivate us and move us. But at the same time, you are able to also notice good things, because in these kind of situations people help out and it brings out their best. Sometimes there are people who take advantage and loot – but this is what makes human society very interesting. For most people, tragedy brings out their best. What happened in New York on 9/11 is a typical example of how human beings have this ability to rise to the occasion. Sometimes we don’t notice this, but I think being able to notice this is very good for us because we don’t want to lose hope; when we give up, then that’s the end of story. If we are able to notice the good side, then it really energizes us and motivates us, and that is why I love that quote. I’d heard about this before but I never really gave it much thought. But during the Boston Marathon bombing, some of the newscasters talked about this and I thought “Yes!” I remembered it, and it is a powerful advice.

Can you talk a bit more on this?

There are numerous practices that I present in the book. One of the things that people who have been completely unexposed to the Dharma, like a VA group in Palo Alto that received an expedited six-week training course, find powerful is the simple exercise of equanimity, recognizing that “Just like me, this person wants to be happy, this person do not want suffering” and learning to use it almost like a mantra. It’s a very simple concept, but for a lot of people who struggle with outrage and short temper when they see someone being unfair, being able to just recall this phrase has been a powerful antidote restraining them.

One of the other things I suggest in the book is intention setting. Those who are brought up in the Buddhist world and those who have been exposed to Buddhism know that intention setting is such an important part of everything that we do. It’s like setting the tone. And whatever tone you set colors what unfolds afterwards. But many people who are not exposed to this kind of idea don’t think about it. For example, if you are running a meeting, if you set a clear intention right at the beginning (you don’t even have to share it with your colleagues, you can do it mentally; it takes only a minute or half a minute) and said, “OK, I’m going to bring my best to this meeting; I’m going to give the benefit of the doubt to everybody and I will recognize that everybody who is making suggestions is going to be making them from the best part of their intention; I will acknowledge and honor them and I will do what is the most wise and compassionate thing to do here,” just setting that intention completely changes the way you would respond and react to other people’s opinions. You wouldn’t take them as a threat or challenge to your views. Those kind of things I think are simple practices, but they have huge, huge implications.

This next question is more relevant to FPMT centers. What is the role of the Western Dharma center in the development of secular compassion? Where do they fit in?

One of the things that His Holiness has expressed in his aspirations for Maitripa College is that in addition to teaching Buddhist studies, the college could teach something that is more universal and that people can utilize regardless of whatever affiliations they may have. I think FPMT is the largest Gelug association in the West and is the fruit of the beautiful vision of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche. You have a tremendous network of sangha members, who have emotional connections with centers all over the world. I think its capacity for outreach is enormous; its presence is everywhere. Also, because of its longevity – FPMT has been in existence for now several decades – there is a depth of resources in terms of experienced people within the community. I would hope that some of the senior members of FPMT would take up this second-level translation that I was talking about earlier, catering to the needs of people who identify with Buddhism and need standard Dharma teachings, but at the same time have the ability and facility to offer this larger, more secular Dharma to people who are simply interested in finding more peace in their life and who are not particularly interested in having any religious affiliation; to people who are looking for some ability to bring more peace into their life, focus more, relate to their family members and the world in a more compassionate way, have a more enriching life, and make their life meaningful and serve society in a meaningful way. That is a very deeply spiritual and legitimate aspiration.

I would hope that the FPMT would think about that because the people who are steeped in the traditional practice are in some ways the best teachers to bring general-level Dharma into more secular contexts with integrity and depth behind it. The only thing that you would need is a little bit of training in the language, because it is a different way of presenting the Dharma. But that is not a very demanding challenge. There are many people teaching mindfulness and so on, but the depth of their personal experience and realization is very shallow, whereas people coming from the FPMT with many, many years of experience and practice, have much greater depth. It’s simply a matter of learning how to present it.

The majority of FPMT members are Western Dharma practitioners, so you don’t have the problem of language. Tibetan teachers are much more used to doing traditional teachings and on top of that they have the problem of language. Their lack of proficiency in English precludes them from having a deeper appreciation of the cultural needs and the cultural sensibilities and nuances of the particular host culture – non-Tibetan FPMT members don’t have that problem.

There are a couple of FPMT centers right now that are beginning to develop projects in this field that we’re talking about. One is Maitripa College, with their Mindfulness and Compassion Initiative. And another is at Instituto Lama Tzong Khapa in Italy, which is developing some sort of science academy. Very early days, you know, but, I was wondering given your experience working at Stanford and with the Mind and Life Institute, what advice you can offer in terms of developing a project and taking it forward.

I think perhaps the most important thing is the sincerity of the motivation because when you have a sincere motivation, you are able to bring a clarity of vision. We are all imperfect human beings, so nobody can come up with a full vision of how things are going to unfold. But where we can make a difference is to ensure the purity of our intention, and also as much as possible, develop a clarity of a vision of what exactly we are trying to do. When these two things are clear, then it becomes a lot easier to actually initiate something. Whoever is in the leadership position needs to have a passionate belief in whatever project they are leading because passion is infectious and can inspire people working on the project as well as funders. It also attracts other people into the movement. If you look at many of the movements, most of them have been successful because there are one or two people who were completely passionate about it – they believed in it – and because of their passion, they are resilient, they don’t get bogged down just because there are obstacles along the way.

A kind of different question, I’m very curious about what your thoughts are regarding the possibility or role of Western high level meditators with realizations – kind of Western yogis – is this something we should be aiming for, is it possible and where might they fit into the development of Dharma in the West?

Yes, that is a very interesting question. There are now, because it has been several decades, high-level Western practitioners who have had high-level realizations. I personally know a few, so there is nothing ethnically obstructing the attainment of these realizations; it really doesn’t matter what ethnicity you come from. The question is how is it that the presence of these yogis hasn’t really translated into the ability for these yogis to inspire people, be in leadership positions, and be great Dharma teachers. That, I think, is an interesting question. I think part of that has to do with the fact that the language of Dharma in English, and for that matter, in French and other languages, isn’t fully settled yet. It is an ongoing process.

Also, I think in the West (although FPMT is an exception), there hasn’t been enough institutional development to really allow the space for Western Dharma teachers to emerge and assume the authority that they deserve. I think these will come. I think it’s probably just a matter of time.

What is very important is that when you have indigenous Western teachers come up, that they be genuine. Tibetans have had the Dharma for such a long time and Tibetan relationships between the guru and students are organic – gurus tend to emerge on the basis of their reputation as teachers and thus there are checks and balances. For example, gurus have attendants who really keep them in check – they are a bit like spouses, keeping you in check. These attendants are very close household members who act as a kind of check on the lama’s behavior. There is very little room for a teacher to go on an ego trip.

In the West, the culture is very individualistic and it is a culture of celebrity – people love fame, people love exposure. There is a danger of someone being put on a pedestal and not having the strength to be able to remind themselves, “Yes, all of this is fine, but in the end, I am who I am.” That kind of groundedness, down-to-earthness, is a quality that needs to be cultivated because in the Western context, generally there isn’t this attendant-lama relationship and things may get out of balance. Also, the culture doesn’t facilitate the development of grounded charismatic teachers. The only model we have are celebrities. Subconsciously, celebrity culture seeps in into peoples’ relationships and those dynamics make it all very complicated. I think these are things the Western Buddhist Dharma centers and cultures will have to gradually learn. I think it is a learning process.

Is there anything that you would like to add or would like to say in to particular to the FPMT audience or anything out that you think is really important?

I think the sense of belonging that the FPMT community has is important. That self-conscious identification with the community is, I think, very important. That will increasingly – even from our own personal selfish point of view – guard students against loneliness and feeling left out and all the rest. In the West, I think we underestimate the importance of community because people are brought up to have very autonomous identities that we should be relying upon ourselves and all the rest. A sense of community is very important. FPMT members are very fortunate because it is a very large community, it has a long history, and Lama Zopa keeps in close touch with all the centers and there is a personal connection with him. I think that should be recognized and valued because there is a Tibetan saying: “When you have a jewel at home, you fail to appreciate its value.”

Geshe Thupten Jinpa is a former monk and holds a PhD from the University of Cambridge. He has been the principal English translator for His Holiness the Dalai Lama for three decades. He is an adjunct professor of Tibetan Buddhist philosophy at McGill Univeristy and chairman of the Mind and Life Institute.

- Tagged: compassion, geshe thupten jinpa, in-depth stories

- 0

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.The office is a place for Dharma practice. When one goes to the office, dealing with people, one has to recognize it’s a place to practice lam-rim, the three principles of the path, tantra, and the six paramitas. The six paramitas fit very well for daily life. They offer protection for you. Everything is there.