- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

27

Dieter Kratzer on Becoming a Teacher

The late Khen Rinpoche Lama Lhundrup with Dieter Kratzer, Tara Mandala, Germany, 2004.

Dieter Kratzer is an FPMT registered in-depth teacher who has been teaching the Dharma for forty years. He spoke with Mandala associate editor Donna Lynn Brown about his development as a teacher from the early 1970s to the present day.

Dieter, how did you meet the Dharma?

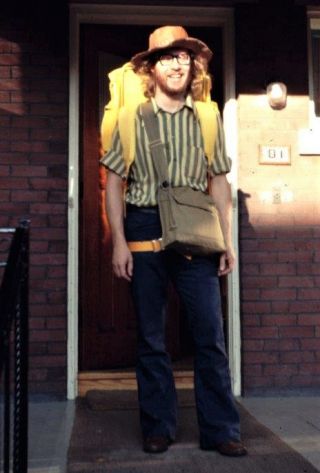

Dieter Kratzer leaving Toronto, Canada, in 1973, a trip that would lead him to Kopan Monastery in Nepal. Photo courtesy of Dieter Kratzer.

In 1972 I left Canada, where I had been living, and went traveling all through Europe into Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan. From there I took the overland route through the Khyber Pass to India. In Dharamsala, I encountered the Dharma, and my first teacher was Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. I met Lama Zopa Rinpoche briefly at Tushita as well. Then I heard there was a one-month course at Kopan Monastery in Nepal, so off I went. That was in 1973. I met Lama Yeshe there and I knew I had found my home. I was ordained in March 1975 by Lati Rinpoche and a year later received full ordination from Kyabje Ling Rinpoche. I lived at Kopan and in Dharamsala from 1973 through 1977, doing a lot of practice and retreat.

And how did you start teaching?

One day at Kopan, in 1975, Ven. Marcel Bertels asked me if I could give a talk about guru devotion. The idea apparently came from Lama Yeshe. I asked when, and he said, “Now!” “I beg your pardon?” I was in shock, but an hour later, I found myself talking to 200 people. That was the start. I was nervous, but people seemed to like it, so that gave me courage.

In the spring of 1976, I was asked to lead a meditation course: forty-five people, twenty-two days. Two nuns assisted, Venerables Karin Valham from Sweden and Elisabeth Drukier from France. I felt I could rely on them and that made me comfortable. And between the three of us we could speak to most of the students in their own language one-on-one even though the teachings themselves were in English.

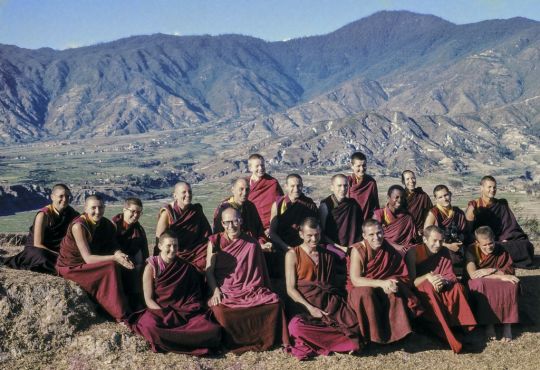

Sangha at Kopan Monastery, Nepal, 1976. Front row, from the left: Yeshe Khadro (Marie Obst), Dieter Kratzer, John Feuille, Thubten Pende (Jim Dougherty), Adrian Feldmann (Thubten Gyatso), Jeffery Webster. Back row, from the left: Thubten Yeshe (Augusta Alexander or TY), Nicole Couture, Margaret McAndrew, Thubten Wongmo (Feather Meston), Nick Ribush, Sangye Khadro (Kathleen McDonald), Scott Brusso, George Churinoff, Bonnie Rothenberg (Konchog Donma or KD), Jampa Konchog (Yogi), Thubten Pemo (Linda Grossman), Chris Kolb (Ngawang Chotak), Marcel Bertels. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Afterward, Ven. Nick Ribush came to me and said, “Well done!” I responded, “How do you know? You weren’t there.” Ven. Nick laughed and said, “My friend from Australia didn’t run away!” That was success in his eyes.

Soon after, I led a second course. These were the first two courses in which a Western teacher taught Western students at Kopan. It was Ven. Nick who asked one day, at Lama Yeshe’s suggestion, if I wanted to lead the next November course. “Why not?” I answered. Lama Zopa Rinpoche was the teacher and I led the meditations, following his advice, and dealt with all the organization. During 1976-77, the Sangha—twelve nuns and fifteen monks—underwent rigorous training in lamrim, and I was asked to design and lead that study program. I still have the notes.

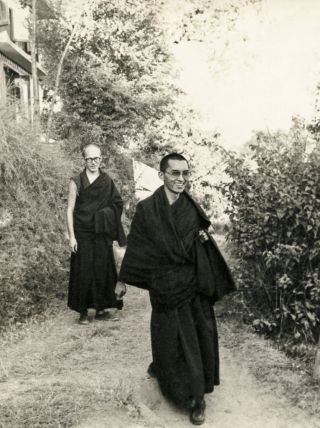

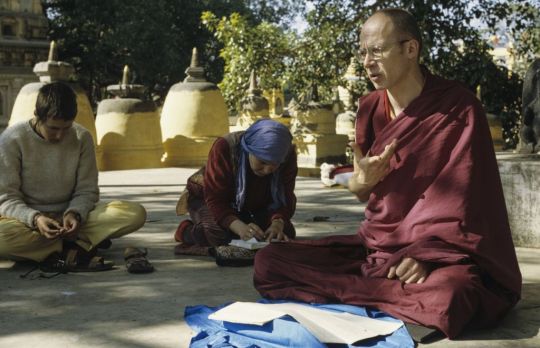

Lama Zopa Rinpoche with Dieter Kratzer, Nepal, 1976. Photo by Dan Laine, courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

At one point, Ven. Marcel asked me to help him run the business he was creating in Kathmandu to support the Sangha. But Lama Yeshe intervened and said that I was not to do business; I was to teach. That was a clear signal. Then Lama asked me to go back to the West and teach there, so in 1977 I left Kopan. I was the spiritual program coordinator at Manjushri Institute in England until late 1979 and gave teachings there as well as elsewhere in England, including at universities: Oxford, Cambridge, Leeds.

How were you handling cultural issues? Being a German teaching in English, teaching an Asian tradition in the West, being a monk among lay people …

My first language is German, but my Dharma language was English, so it was easier for me then to teach in English than in German. Later, when I was back in Germany after having spoken English for so long, I had trouble finishing sentences in German, because I translated them from English! It wasn’t English that was the problem for me.

As for Tibetan Buddhism being foreign: I didn’t find that I needed to make many adjustments in those days. It was OK back then to be exotic. That was expected, even preferred. People were looking for a change from Western culture. And they accepted the traditional ways of teaching that I had learned from the lamas, especially from Lama Yeshe—he was my idol. The way he communicated was unbelievable, and it was my great wish to be as much like him as possible. My way of starting talks in those days was saying, “Buddhism is about you. It’s about your feelings, your hopes, your fears. It’s about your mind and how you work with it.” That opened people up to listening. Then cultural differences seemed irrelevant.

Later, I started to understand that there were still cultural issues, especially being a monk around lay people. Here is an example. I left Manjushri in 1979, taught in France for a time, and then got an order from Lama Yeshe: “You go Germany. You make center.” So I established the Aryatara Institut, as it is now known, in Munich. I organized teachings there and gave teachings myself.

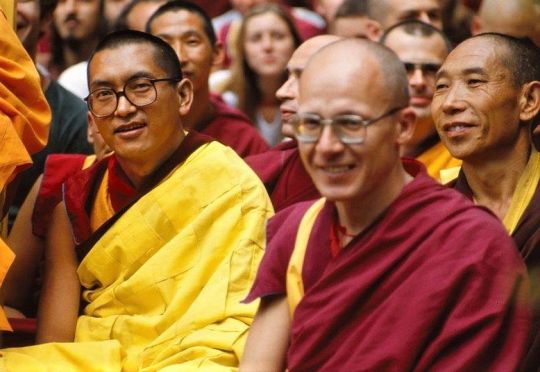

Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Dieter, 1976. Photo courtesy of Dieter Kratzer.

That’s when I first noticed clashes between the Asian tradition I had taken on and European ways. There were seven of us living in a residential Dharma center in the country: three laymen, three laywomen, and a monk, myself. I had done lots of retreat—a few years in total, in Lawudo and Dharamsala and so on—something Lama Yeshe had emphasized. So I had a bit more Dharma knowledge. And that came out when we chatted about Dharma around the kitchen table. It didn’t go down well, to be honest, and I wasn’t sophisticated enough to be skillful. I had no mentor to discuss it with; I was on my own. For the others, it was challenging having a monk around: some people were comfortable with my robes, but others had trouble relating. They would criticize me for small things: if I wanted to stay in silence for a while they would say, “Why don’t you talk?” but if I talked, they would say, “Why are you talking?” Lama Yeshe had told me to wear lay clothes when I went to town, but the others didn’t like that. And so on.

Teaching was the part that went well. In German culture, when you explain why you do things, people feel comfortable. It bridges the cultural gap. So I explained a lot: why we do prayers, mandala offerings, prostrations, everything. People understood that and liked it. So teaching was where I felt I was succeeding. And teaching was what mattered most to me anyway. But I found the social side painful.

The gates of Nalanda Monastery, France

After several years I left Aryatara Institut and went to live at Nalanda Monastery in France. I was again the spiritual program coordinator. I knew a little French but I taught at Institut Vajra Yogini in English. There I didn’t perceive cultural obstacles: when I taught, the students hung on to my words. They were like sponges, that’s how badly they wanted the Dharma. That made teaching a joy. So France was a decompression after Aryatara. I was happy there.

After a few years at Nalanda, I had worked for a long time and I asked Lama Yeshe if I could do some retreat. “You come to India at the beginning of next year,” he said, “and you and I, we go to meditate together.” Can you imagine? I was overjoyed. Then he fell ill; he died in March that year. That was hard.

I’m guessing that the passing of Lama Yeshe ended one phase of your life in the Dharma. How did you regroup and go on?

I didn’t go to America for Lama Yeshe’s cremation. I had talked to Lama Zopa Rinpoche who had talked to Lama Yeshe, and Lama Yeshe advised that I go to India to do retreat. And so I went. Lama knew I wanted to keep teaching, but I needed a chance to go deeper into practice so that when I taught again, I would have more to offer. To teach, one needs real experience of the Dharma; that is essential. We have to become the Dharma to teach the Dharma! I stayed in retreat for almost two years. When I finished, it was 1986 and Lama Zopa Rinpoche sent me to Singapore via Hong Kong.

Dieter Kratzer teaching on vows at the request of Lama Yeshe, Main Stupa, Bodhgaya, India, 1982. Photo by Ina Van Delden, courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

What did you do in Hong Kong?

I taught Westerners in Hong Kong for a few months. At first I taught only in the traditional way. But that didn’t attract many people. “Exotic” wasn’t the fashion any more. So I started explaining things in a more psychological way, more in tune with the Western mind. The result was dramatic. I had started with only three or four people and within a few weeks over forty people were attending. I realized that, while the purity of the teachings had to be kept, for Westerners, it was better if explanations fit their culture and mindset.

What was it like to teach in Singapore?

Lama Yeshe had said, “We have to expand to the East.” In Singapore, the culture is Chinese, but I knew nothing about Chinese culture, nothing at all. It started well: I was a monk, which gave me automatic respect. People listened avidly and soon I had up to 150 people at every talk. I stuck to a traditional approach for the most part. For example, when I talked about the four noble truths, I didn’t hesitate to talk about how much suffering we can experience. But I experimented a little. I discovered that I could explain the lower realms both literally and psychologically. The same was true of refuge: I learned to explain it both literally and psychologically, meaning that one can develop into one’s own refuge; one can develop the Three Jewels in oneself. So I ended up teaching not exactly the way I taught to Westerners but not totally traditionally either. Teaching in Singapore was generally a success, I thought. And as the first Western FPMT teacher to be sent there, I was able to play a part in establishing Amitabha Buddhist Centre. That felt good, and still does.

Lama Yeshe visiting Singapore, 1984

But personal interactions were more difficult. People were kind to me, and I was invited for meals, taken out for rides, shown the countryside—yet the cultural differences started to show. At first I behaved just as I would in Europe. But I came to realize that I needed to be more careful about how I talked, for example, to ensure that no one ever lost face due to something I said. When that happened, I discovered, the person involved would not see me or talk to me again. I didn’t make a lot of mistakes, but I made a few, and that was enough to create difficulties.

My greatest challenge was my robes, which led me to be seen as “holy.” Sure, I had done some retreat and study, but I still felt I was an ordinary person with many weaknesses. The way people saw me and the way I saw myself were so different, I could not reconcile it. In a way it was nice to be treated as special, but I knew I was not special in that way. There was an outer me that was too distant from the inner me, and that left me deeply unhappy. I wanted authenticity, to be the same inside and out. So I ended up thinking hard about ordination.

I also started to feel more and more lonely. I would give a talk to maybe 150 people, then someone would take me home and I would be by myself. The contrast was striking. Around that time a woman appeared in my life, unplanned. My inner quandary made me open to someone who really saw and cared about me, my troubles as well as my virtues. This process of discernment about keeping my robes lasted quite a while. I still wanted to teach; that was what mattered most. I asked Lama Zopa Rinpoche if I could teach the Dharma as a layperson. He paused for a while, but then said yes. In the end, my main reason for disrobing was not attachment, but rather my sense of dislocation or disorientation. Still, my loneliness was the final straw, and I disrobed.

Prajnaparamita with Devotees, folio from a Shatasahasrika Prajnaparamita, Tibet, 11th century. Photo by Ashley Von Haeften. Flicker Creative Commons.

How did that affect your life as a Dharma teacher?

I lived for a while in France. There, I knew a couple who were running a small meditation group. They asked me to give a talk. I hadn’t done that since I disrobed. I hesitated; I was very unsure of myself as a teacher without my robes. They urged me to try. So I gave a talk in a mix of English and French: my French was not so good. And their response was overwhelming. They were happy, and more important, they connected with the teachings and with me as a person. I discovered that I could communicate better without the barriers the robes created. When they said that I explained the Dharma in a way that let it enter their hearts, it was a breakthrough for me. It was one of the highlights of my teaching life. And it gave me the confidence, the inner security, to teach again. I knew I could pursue what was most important to me in life: teaching the Dharma.

How did the next phase unfold?

For a while, I traveled a lot to teach: Europe, Australia, various places. And I did fifteen months of retreat at O.Sel.Ling in the Spanish mountains. This was the early 1990s. Lama Zopa Rinpoche then asked me to go back to Aryatara Institut in Germany as the director and teacher: a big job. I worked sixteen-hour days, seven days a week. Eventually, I went out on my own. I was teaching various groups; people would invite me and I also still taught at Aryatara. After a few years of traveling around, I meet my wife, Maria. We hit it off from the very first! So fantastic.

Dieter with his wife Maria. Photo courtesy of Dieter Kratzer.

I’m guessing that brought more changes.

Yes. In 1996, we moved to a small town not too far from Munich. I began to give teachings in our home, first to two or three people, but quickly the number of students grew and we built a meditation hall that could hold up to fifty people. With the blessings of Lama Zopa Rinpoche, we called it Tara Mandala. We also bought the property next door as a guest and retreat house. Khen Rinpoche Lama Lhundrup visited us in 2004 and recommended that we ask to be part of FPMT; first we became an FPMT study group and then an FPMT-affiliated center in 2008. I have taught full time there for the last twenty years.

What factors have helped make you a good teacher?

In the early years, I used to think that because I had knowledge and could talk well, I was a bit special. It was a lack of humility really. I soon realized that I had to have an attitude of learning from my students. They showed me where I could improve. For example, once I was teaching in England, and Rob Preece, who is an FPMT registered teacher himself and a psychotherapist, was acting as my assistant. I gave a talk on how reincarnation works. Afterward, Rob said, “Dieter, that was garbage! No one knew what you were talking about!” I was fuming. But I went back to my room and reflected. Although it was painful, I realized that he was right. The next day, I taught the same topic but in a different way. When I looked at Rob’s face, I saw he was smiling. I felt so grateful. So I started out thinking that everything I taught was OK, and fortunately some people, like Rob, told me where I had to do more work. That was how I developed as a teacher.

I also believe that teachers have to be a living example of the teachings; the teacher can be the teaching. That means not just having experience of the Dharma, but also living one’s life in a way that inspires confidence and forms the basis of good relationships with others. I have a lot of help from my wife in this. We’ve been together for more than twenty years and we live very harmoniously. She supports me and I support her. Our example inspires people, and that makes us happy and gives us strength to continue. Lama Yeshe said, “If there is energy, there is center. If no energy, no center.” Keeping a center going is tough. It is important, as a teacher, to stay in one place, to be available to meet people’s needs. That’s different from traveling teachers. They don’t have this close relationship with students. Setting an example and having good relationships are both part of transmitting the Dharma. Lama Yeshe said once, “We want quality, not quantity.” That stayed in my mind. For me it’s best to have small groups and work closely with people. So I teach small groups, ten to twenty-five people, a few times a week, year round, in a way that I get to know people and they know that they can rely on me.

Dieter with students at Tara Mandala, Germany. Photo courtesy of Dieter Kratzer.

Another factor. Even though I must be one of the longest serving teachers in the FPMT, I still prepare for practically every lesson, out of respect for the students. I prepare the content, I collect my mind, I concentrate on the subject matter. In a way I don’t have to: I can talk off the cuff now on almost anything. But I don’t. Every student is different, every group is different, and I open my mind so that I can tune in; I get a feeling for those present and teach according to that feeling. I think this intuition comes from having the inner conviction that what I am doing is the best thing in the world—there’s nothing better than teaching the Dharma.

So teaching is my profession, my vocation. I have learned over the years various ways to express the Dharma so that different people can relate to it, can make it a living experience. When I teach, I may choose certain words or analogies. Others can’t see this, but it may have taken me years to develop that particular approach to a subject. A lot of hard work, thought, and experience go into this. Having had forty years to deepen my own practice and sharpen my teaching skills—what a precious gift!

The cobbled courtyard of Tara Mandala, Germany. Photo courtesy of Dieter Kratzer.

What are your thoughts about how best to transmit Buddhism to the West?

The message is an old message. Yet it is up-to-date in its description of the human condition. The message has to be passed on, but that means explaining it so that people can relate to it, even if that varies by culture. At one point when he was visiting Germany, Lama Yeshe told me, “When you are in Germany, you teach German Buddhism!” He meant I should use my own wisdom to adjust my teaching to each environment—along with always taking care not to water down the meaning, but to keep the purity of the lineage I received from him. That was a challenge—but satisfying when I felt I succeeded. So although I vary my style of presentation, essentially I teach the words of the Buddha as explained by Lama Yeshe, who was the perfect teacher.

Fundamentally, we are not Germans or Tibetans, we are just people who suffer. The minds of people everywhere are pretty much the same. I see my role as doing everything I can to alleviate that suffering.

How would you describe your life as a teacher right now?

Who would have guessed that I would teach the Dharma for forty years? To run a center and teach there, with my amazing wife beside me, to see her children grow up in the Dharma, to have two grandchildren as well—they are seven and three years old and learning to do prayers and prostrations! I couldn’t be happier; I couldn’t be more fulfilled. Looking back over four decades I know in the depths of my heart that teaching the Dharma is the greatest privilege a person can enjoy. It is thanks to the kindness of my guru Lama Yeshe that I have been able to do this. I want to go on as long as my body and mind allow. I am determined to teach for many years to come!

Mandala is offered as a benefit to supporters of the Friends of FPMT program, which provides funding for the educational, charitable and online work of FPMT.

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.Our grabbing ego made this body manifest, come out. However, instead of looking at it negatively, we should regard it as precious. We know that our body is complicated, but from the Dharma point of view, instead of putting ourselves down with self-pity, we should appreciate and take advantage of it. We should use it in a good way.