- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

28

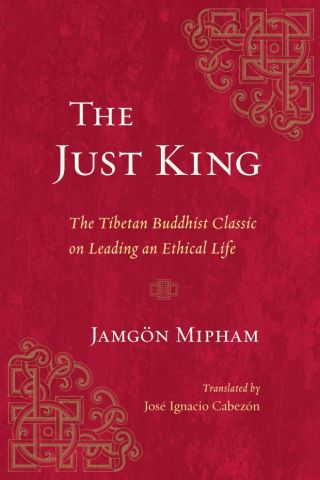

Buddhist Conduct: A New Resource from Old Tibet

Prayer flags and mani stones near Lawudo, Nepal, 2019. Photo by Harald Weichhart.

The Just King: The Tibetan Buddhist Classic on Leading an Ethical Life has recently been published by Snow Lion/Shambhala. It presents a lengthy work on ethics by Tibetan luminary Jamgön Mipham (1846-1912) translated by distinguished scholar-practitioner and former Sera Je monk Dr. José Cabezón. Mipham’s text is one of the most comprehensive works on Buddhist ethics ever written, and deals with ethical self-cultivation, interpersonal behavior, social justice, criminal justice, government, management, taxation, the environment, and many other topics. Although Mipham was a Nyingmapa, his text is a summary of Indian sources foundational for the Gelug and other Tibetan schools. It draws on several sutras, including the Sutra of Golden Light, a favorite of Lama Zopa Rinpoche, to which Mipham devotes an entire chapter; and several Indian ethics and advice texts, including Precious Garland, Letter to a Friend, and The Staff of Wisdom by Nagarjuna. Mipham synthesized these works with the popular “mi-chö,” or “folk” teachings of Tibet concerning proper or beneficial conduct. Thus, his book is quintessentially Tibetan Buddhist, drawing on both canonical Indian Buddhist sources and traditional Tibetan wisdom.

In this article, Donna Lynn Brown, former Mandala associate editor and graduate of Maitripa College, discusses The Just King in the context of a conversation with Dr. Cabezón and some reflections on the teaching of Buddhist ethics from FPMT-registered teacher Don Handrick.

A Simple Question

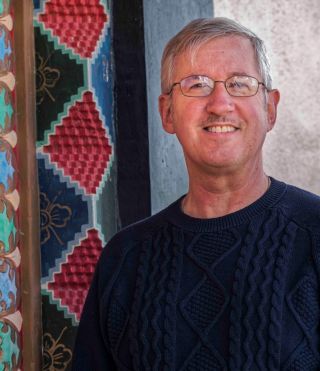

Dr. José Cabezón giving a talk at Maitripa College, Portland, OR, US, September, 2016. Photo by Laura Miller.

How should Buddhists behave? It’s a simple question—but it doesn’t have a simple answer. Buddhists often vary in their views on ethical issues. Nevertheless, FPMT-registered teacher Don Handrick offers an important starting point: in his experience, most Buddhists want to live in accordance with Buddhist ethical teachings. But do we know what those are? Although the lamrim and mind-training texts used for teaching basic Dharma explain compassion and karma, which ground Buddhist morality, they do not always provide details on how to live ethically in the modern world. Teachings on ethics can be found in sutras and commentaries as well, but it can be hard to determine which texts are most relevant today. The specifics of Buddhist conduct are thus not taught all that often in Dharma centers.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche consistently recommends the lamrim and Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand by Phabongka Rinpoche as sources on the ten non-virtuous actions. Handrick has also taught Atisha’s brief work The Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland, which contains useful material on living responsibly in the modern world. He notes that people in FPMT sometimes navigate interpersonal issues using A Practical Guide of Skillful Means, FPMT’s training manual for its Foundation Service Seminar, which he calls an effective resource. He has also been examining the secular ethics presented by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in his book Beyond Religion for potential use in teaching difficult modern topics.

Don Handrick, Santa Fe, US, February 2017. Photo by Jack Mitchell.

Teachings on social and environmental justice are particularly rare in Tibetan lineages. For these, one option Handrick has taught is Active Hope by Joanna Macy, a Buddhist teacher influenced by Tibetan and Theravada Buddhism as well as Western thought. He likes its combination of both Buddhist and contemporary views on caring for the planet and its inhabitants. And Tibetan lek-she texts, containing verses of advice, like Sakya Pandita’s famous Treasury of Good Advice and Gelug luminary Gungthang Rinpoche’s The Water and Wood Shastras can provide a foundation for discussion and reflection. Yet while His Holiness encourages engaged Buddhism, Handrick notes that there is a shortage of texts in the Tibetan tradition to help Dharma students determine how important social action is to a life in the Dharma, what social issues are imperative to tackle, and what stand on any given issue is “Buddhist.” At the same time, he perceives a growing interest from Buddhists in teachings on social justice.

The bottom line is that there is no single comprehensive work in the Buddhist canon that encapsulates teachings on ethics and social justice in a way that crosses cultures and eras. The broadest and most systematic ethical works in Buddhism are likely the monastic law codes found in the vinaya, but these are not intended to guide lay people’s lives. Given this, it seems there is room for another text that addresses not just personal morality for lay people, but also how to promote social and environmental justice, and that integrates teachings from a number of valid sources. That’s what José Cabezón thought too when he started reading Mipham’s book with graduate students in a Tibetan literature class.

A Potential Answer

The more of Mipham he read, Cabezón reports, the more intrigued he became, and the more convinced that the text deserved to be translated. He explains: “Mipham’s great contribution was to synthesize all of the relevant Indic and Tibetan materials. His work is a digest of all of the ideas on ethics, governance, and social justice found in the Buddhist Sanskrit literature and the ‘folk’ literature of Tibet. To my knowledge, no other work, Indian or Tibetan, ancient or modern, does such a thorough job of bringing these sources together.”

Courtesy of Shambhala Publications.

So the text is comprehensive. Is it also relevant? Cabezón says, “Mipham advocated a wide range of ethical principles. These include non-harming, cultivating virtue, caring for the poor and vulnerable, respecting all religions, not damaging the environment, a fair criminal justice system, and a government responsive to social needs. These principles are as relevant now as they were when Mipham was writing. And the text is clearly Mahayana—it has an ongoing focus on the role of compassion in ethical conduct, and it emphasizes the importance of engaging with the ordinary world.”

“Buddhism,” concludes Cabezón, “has a lot to say about the issues we face today. And Mipham’s text is a useful guide. It applies to everyone. And it is readable. Mipham makes Buddhism’s teachings on ethics and social responsibility very accessible.”

The book is long, and a brief article can’t do it justice. But it might be useful to summarize some aspects of its approach. If, as Handrick has found, Buddhists wish to practice ethics and social responsibility grounded in Buddhist teachings, they need to know what these are. Some of the answers are in The Just King. To be clear, many ethical standards taught by Mipham are in accord with modern secular ethics. Areas of overlap in the category of personal morality, for example, include directives like compassion/non-harming/helping others; not lying/being honest/speaking helpfully; and not stealing/protecting others and their property. Cabezón notes that “a lot of the ethical principles that Mipham outlines will be familiar to Western readers.” That’s a good thing: most Buddhists will not want to discard contemporary ethics, based on equality, human rights, and justice. And Mipham, drawing on the same traditional Buddhist sources that the lamrim does, sees the ten non-virtues as universal wrongs: just what those trained in lamrim would expect.

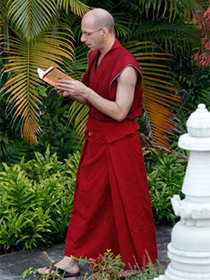

Nun reading a text. Photo by Olivier Adam.

What Distinguishes Mipham’s Approach to Buddhist Conduct?

A starting point: the book emphasizes that personal morality is the basis for all other aspects of conduct, including working for justice. Mipham places ethical self-cultivation first. This teaching applies to rulers and leaders, but its basic principle—that one cannot guide others, or act beneficially, without having first cultivated virtue oneself—applies to everyone. And being a good and ethical person is not a minor practice, quickly accomplished; personal integrity develops over time as individuals learn and apply numerous ethical standards, implement proper conduct, and develop virtues in a plethora of areas that Mipham describes. Interestingly, Mipham also prioritizes self-care: that taking care of one’s own body, mind, and worldly life is required to create a healthy foundation for Dharma study, contemplation, and action. Pure morality, self-care, and self-cultivation are thus interconnected, and form the basis for activity in the world.

Don Handrick observes that “Dharma students’ views on Buddhist ethics and conduct tend to be based upon non-harm, in line with the idea that His Holiness articulates: ‘If you can, help others; if you cannot do that, at least do not harm them.’” Morality for Mipham also starts with avoiding the ten non-virtues and other forms of harm. Wisdom is key to this; it lies behind all good conduct. This is not necessarily wisdom about ultimate reality; it is developing, through study and experience, the intelligence to distinguish between good and bad, right and wrong, truth and deception, justice and injustice, fairness and unfairness. This is a ruler’s responsibility first, since rulers set the standard, but it is vital for everyone.

In addition, Mipham identifies numerous good qualities to cultivate. He promotes disciplined, respectful, and humble behavior, but also having self-confidence based on a realistic recognition of one’s own abilities, not tolerating bullying, and knowing and pursuing one’s own goals even in the face of impediments created by others. He favors self-knowledge, assertiveness, and perseverance. He praises helpful speech, keeping one’s word, and being honest and truthful, but he is also realistic and advises his readers to analyze others’ speech and determine when they are being dishonest. He teaches that one should be a loyal friend, and adds that one must rely only on good and truthful friends and advisors, avoiding ill-motivated or misleading people. He offers much good advice for running organizations, managing staff fairly and kindly, keeping good boundaries, and even working with lamas and teachers. There is far more; these are just some examples of his advice for living wisely and cultivating goodness.

A second key point: Mipham connects living ethically, for everyone, to a more stable and sustainable world. He cites rulers to begin with. One reason why those in power are instructed to be ethical is that their behavior influences that of everyone else. Comments Cabezón, “Mipham considered that righteousness would trickle down from the ruler to his ministers to the people.” So there is a need to demand principled leadership from those in power.

But Mipham’s canonical Buddhist sources go on from there to teach that the ethical conduct of citizens as well as rulers drives the sustainability, prosperity, and happiness of a country—including its climactic conditions and environment. In other words, there is an order that, when disturbed by inappropriate conduct, reacts by bringing on illnesses, wars, devastating weather events, crop failures, famine, diminished wealth and lifespan, and other disasters. Given its impact, personal morality thus becomes a social responsibility. But so does working for justice, because unresolved injustices are environmentally disruptive in the same way as flawed personal behavior. Both lead to catastrophe.

That transgressions against morality and justice are at the root of environmental and social collapse is not precisely the contemporary way of thinking—and yet the idea accords well with the modern acceptance that harmful or unjust human actions are damaging society and the planet. Mipham only adds that personal conduct is a part of this too. This notion seems to be supported by Lama Zopa Rinpoche, who in 2009 said with reference to climate change: “People think, ‘This is a natural disaster,’ but it doesn’t happen without a cause, and the main cause is karma … of course, there are conditions, such as pollution from cars, etc., that we commonly understand. But we have to understand there is a reason, and that is our past negative thoughts and actions. … We don’t normally talk of karma in a general situation regarding the environment, but it is important to educate people.”

A third distinguishing feature of the work is its descriptions of what constitutes good government and a just world. Mipham cites a wide range of factors, such as:

- A fair criminal justice system, where wrongdoers are stopped and punished, but with compassion rather than vengefulness, and without capital punishment. Mipham recommends equality before the law: even kings are subject to the law, and punishments should not vary based on offenders’ wealth or social standing. The law should keep honest people safe and ensure victims receive fair treatment.

- Ending corrupt behavior by those in power, with offenders banished.

- Impartial respect and protection for all “ancient” religions. Both conflict among religions, and their blending into a single “pastiche,” should be discouraged by governments.

- Protection by governments for the environment and all the living beings in it, as well as for homes, crops, cultural treasures, art, and architecture.

- Fair taxation. Individuals should not begrudge the payment of their fair share of taxes, but taxation should be on a sliding scale, with the wealthy paying a higher rate and the poor paying only small amounts or nothing at all.

- Discouragement by governments of income inequality.

- War as a last resort; all efforts must be made to maintain peace. If a war is inevitable, lives and property must be protected to the extent possible.

- Protection and care by governments for the poor, elderly, vulnerable, and suffering, and all citizens in times of natural disasters, famines, and so on. Governments should also protect visitors to the country.

- Assurance of the well-being of ordinary people by governments, by building hospitals, schools, parks, roads, and bridges; by supporting artists, dancers, and musicians; and by ensuring that everyone has a means of livelihood.

In this manner, Mipham reveals what a good society might look like, and thus points at potential areas of social justice that Buddhists can pursue.

Trashichhodzong Monastery in Thimphu, Bhutan, taken during Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s visit, June 2016. Photo by Ven. Roger Kunsang.

The Challenges of a Pre-Modern Text

Is there anything not in the book that we might expect to find? Well, there is no mention of vegetarianism, even though Mipham speaks repeatedly about caring for animals. Given that some of Mipham’s Indian sources opposed meat-eating, Cabezón attributes Mipham’s silence on the practice to a sensitivity to his Tibetan readers. The book also contains little material on love or sex. Mipham stresses the avoidance of sexual excess and adultery, but does not dwell on other aspects of intimate relationships. With respect to government, Mipham offers a great deal of material on how countries should be run, thus giving readers measures by which to judge policies and leadership. Yet he also teaches that bad leaders will fall from power without citizens themselves taking action. Don Handrick observes that many modern Buddhists are seeking practical advice on Buddhist ways of engaging in political and social action. Mipham provides little guidance in this area.

It is worth noting that Mipham is not a moral relativist. In his eyes, morality and ethics are mainly universal and rule-based, not situational: there are clear rights and wrongs. Nevertheless, he is quicker to prescribe compassion or patience for the shortcomings of ordinary people than for wrongdoing in high places. This soft spot for the common folk, and particularly the downtrodden, may be related to the Mahayana orientation of Mipham and his sources, and is one of the most appealing aspects of the book.

Are there any teachings in the book that are not suitable for modern Buddhists? Cabezón notes, “In a couple of instances, Mipham reproduces verses from the Indian tradition that see women as manipulative, untrustworthy, and in need of control. Such verses need to be seen within their social and historical context—but it is appropriate to critique them.”

Given the historical setting, it is not surprising that Mipham also lacks a clear concept of human rights. This shows up in his references to slavery, which he takes for granted and does not denounce. His acceptance of slavery parallels his acceptance of male control over women. For example, in a verse on theft, he gives instructions for dealing with the theft of “wives and slaves”—a special kind of property, it seems. Such were the times. Mipham teaches that women, servants, slaves, enemies, evil men, and animals should be objects of compassion, care, and protection. Yet they do not have what would now be called “rights.” Mipham’s acceptance of a social structure in which some people have wide-ranging control over others does not negate his good advice in countless other areas. But it is a reminder that readers will need to use judgment, and adopt teachings that meet modern as well as ancient moral standards.

Conclusion

Overall, The Just King is a practical resource for those interested in Buddhist approaches to good conduct. The ethical implications of important sutras and commentaries, such as the Sutra of Golden Light, are explained in a readable and accessible way. Much sound advice for living in the world is offered. Importantly, aspects of what a just world might look like from a Buddhist perspective are described, providing a potential basis for Buddhist social engagement. While some teachings in the book will need reappraisal in the modern context, most are strikingly apt, and all can promote fruitful discussions on Buddhist priorities, values, and conduct.

Photo courtesy of Dr. José Cabezón.

José Cabezón, Ph.D., is a professor at the University of California in Santa Barbara, US, holding the XIV Dalai Lama Chair in Tibetan Buddhism and Cultural Studies. He studied with Geshe Lhundub Sopa at the University of Wisconsin, was a monk for ten years, six of them studying at Sera Je Monastery, and has published several distinguished books as well as countless academic articles. His two latest works, Sexuality in Classical South Asian Buddhism (Wisdom Publications) and The Just King (Snow Lion/Shambhala Publications) are being published in 2017.

Find more information on FPMT-registered teacher Don Handrick:

https://www.donhandrick.com

Go to the FPMT Online Learning Center’s Discovering Buddhism course to learn more about the ten non-virtues, karma, and other topics related to this article as taught by Lama Zopa Rinpoche and FPMT-registered teachers.

Mandala is offered as a benefit to supporters of the Friends of FPMT program, which provides funding for the educational, charitable and online work of FPMT.

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.The sun of real happiness shines in your life when you start to cherish others.