- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

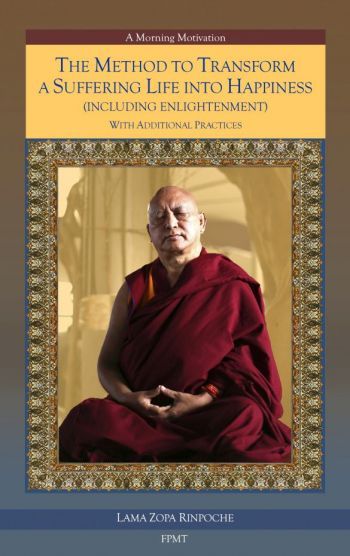

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

The root of your life’s problems becomes non-existent when you cherish others.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

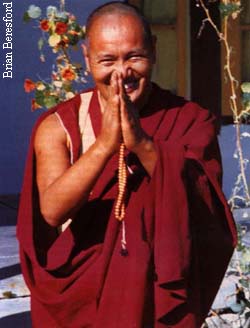

A Tribute to the Life and Work of Lama Yeshe

Venerable Lama Thubten Yeshe

1935-1984

Lama had been seriously ill for four months, although according to Western medical reports since 1974, it was a miracle that he was alive at all. Two valves in his heart were faulty and because of the enormous amount of extra work it had to do to pump blood, it had enlarged to about twice its normal size. And he himself had said ten years before that he was alive “only through the power of mantra.”

Here, Lori de Aratanha and Robina Courtin report the events leading up to and immediately following the passing away of this great yogi and teacher, an extraordinary man who moved the hearts of thousands during his fifteen brief years among Westerners.

Lama had arrived back in India in early October after a strenuous teaching tour of Europe and America. From Delhi he travelled to Dharamsala where he had a house in the grounds of the Tushita Retreat center. Here he stayed in seclusion.

Lama was not scheduled to go to Nepal to teach as he had done for fourteen years at the annual Kopan meditation course. Vicki Mackenzie, a London journalist and friend of Lama Yeshe for eight years, was at Kopan for the course. ‘We were told that Lama was too sick. We didn’t know where he was but we did know that he would not be coming. But, a couple of days before the end of the month-long course, suddenly. like magic, he appeared.

‘It was morning. We all came out of the tent to greet him. It was so moving and terribly touching. All the small monks of Mount Everest Center were lining the road, the older monks on the roof of the gompa blowing conches and trumpets out over the valley. And everyone was so silent. There was such an incredible hush. Somehow it was very poignant and very holy. Lama Zopa went up to the land rover to greet Lama with unbelievable reverence, love just pouring out of him. Catherine and I, and others, burst into tears. It was so special and so moving.

‘The silence was extraordinary. So unlike the usual joyful pandemonium of the monastery. We didn’t know anything but somehow we felt that this was very, very special.’

And Lama Yeshe did teach. Two days later, at the end of the course, he gave first a question-and-answer session and the following day a four-and-a-half-hour teaching on refuge and bodhicitta.

‘It was extraordinary,’ said Vicki. ‘For one month the hundred of us had been immersed in the serious business of a Iam rim course. It had been very intense. There had been much anguished discussion about the various traditional teachings Lama Zopa had been giving us.

‘When Lama walked in I knew immediately that he was very ill. Still so caring though, and joking: “Oh. I don’t know what I’m talking about!” But always so kind, so concerned about us. “Are you all right? Are you tired?” he would ask us. He showed just so much love.

‘His answers were marvelous, somehow exactly what we needed. He completely demolished all our dualistic, narrow concepts. “Your Mickey Mouse minds! You are so boxed in, so narrow,” he said. Somehow, his words were like a miracle. He spoke such utter common sense, made everything seem so simple. Our confusion and worries simply dissolved away. He knitted everyone together, cut across all divisions.’

‘He said he was fine. He took my hands and before leaving asked me to “give my love to all my dharma brothers and sisters in England.”

‘Lama had told me in an interview in 1978 that he “should have been dead years ago. But if someone tells you you’re going to die, what can you do but give up? I don’t give up,” Lama said. “What these doctors don’t see is that human beings are something special. We are beyond the ordinary concepts of what we think we are.” That night, December 10th, Lama began vomiting and experiencing difficulty in breathing. He did not sleep, nor did he sleep the next night. On the morning of the 12th it was decided to take Lama to Delhi for urgent medical treatment.’

He traveled to Delhi with Karuna Cayton, an American student of Lama based at Kopan, and was admitted into the intensive coronary care unit of a good hospital. He stayed altogether for fifteen days under the close observation of two highly respected cardiologists. On January 1st Lama was released and remained another month in Delhi to recuperate.

On January 3rd Lama allowed—for the first time, according to Lama Zopa—mandala offerings to be made to him for his long life. On behalf of all his students, Australian monk and director of Lama’s Dharamsala retreat center Max Redlich fervently requested Lama to live longer. Lama agreed that he ‘could live for another two years.’ He told Lama Zopa at this time that he ‘could live for ten, twelve years, but it depends on the karma and hard prayers of the students.’

Since Lama had left Kopan on December 12th he had insisted that Karuna keep complete silence about his condition. In early January, Geshe Rabten, one of Lama’s dearest teachers, stayed with him in Delhi. He instructed Lama ‘to lift your cloak of silence. You should let people know about your condition so that your students can create merit.’

On January 8th Karuna wrote a letter to Lama’s students at his centers detailing the past month’s happenings.

Lama’s heart was now failing so badly that congestion in his heart was making breathing difficult; congestion in his liver and other abdominal organs were causing pain and vomiting.

By early February it seemed clear that Lama should undergo surgery to replace his faulty heart valves. Stanford Hospital in California was chosen.

Lama Yeshe arrived at San Francisco Airport, two hours from Stanford, on February 3rd. He was accompanied by Lama Zopa, who had been with him constantly for the past month, American nun Max Mathews and his Indian doctor. He was met by John Jackson, director of Lama’s California center, Vajrapani Institute. Lama looked ‘weak and surprisingly thin,’ but still had his vibrant smile. He was driven straight to Stanford Hospital.

Registered nurse and student of Lama Yeshe, Shirley Begley, volunteered her services. She arrived at Stanford on the sixth. The results of the extensive tests on Lama confirmed previous diagnosis, and doctors suggested surgery as soon as he was strong enough.

On February 8th Lama was released from hospital and allowed home, where he would have full-time nursing care: Shirley would be joined later by Lennie, another nurse, Barbara Vauier and others.

Lama was driven to his home in Aptos, an ocean-side suburb of nearby Santa Cruz forty-five minutes from the Vajrapani land. The house, overlooking vast expanses of the Pacific, had been bought for Lama and renovated by some of his students.

He preferred to be home. He enjoyed his garden, and within two days was pottering around outside. But by the twelfth Lama was feeling faint and could no longer hold food down. He remained in bed and needed constant nursing.

Shirley was worried. Her medical experience told her that definitely Lama should be back in hospital, but he did not want to go. ‘I don’t need to go,’ he said. ‘You don’t have to worry.’

Throughout the entire period of Lama’s illness, Lama Zopa was in constant touch by phone with Kyabje Song Rinpoche in Switzerland as to when and how to act for Lama’s benefit. He also consulted frequently His Holiness Dudjum Rinpoche in Paris. And he himself would always make observations in the traditional manner whenever decisions were needed.

Often, this proved difficult for the nurses: their observations as nurses told them one thing and Lama Zopa’s would tell them another. However, they learned, they said, to let go and in retrospect can see the benefits of the decisions that were made.

On the evening of February 15th, Shirley was in the kitchen with Rinpoche. Lama was asleep in his room. Shirley was explaining to Rinpoche her perception of the seriousness of Lama’s condition. Understanding the importance of Lama Zopa in the decision-making process, she wanted to clarify with him just how much responsibility she had. She asked Rinpoche if she could make the decision to hospitalize Lama if an emergency situation arose. ‘You mean to save Lama’s life?’ Rinpoche asked. ‘Yes,’ said Shirley. Rinpoche agreed that she could.

Just then Lama’s bell rang from his room. They rushed to him and it was immediately obvious to Shirley that Lama had had a stroke. She took his blood pressure and Rinpoche gave him some Tibetan medicine. Rinpoche agreed they should call an ambulance, which arrived five minutes later and rushed Lama to a nearby hospital. The stroke was severe. The left side of Lama’s body was paralyzed. In spite of this, and against his doctor’s advice, after one night in the hospital Lama insisted on going home.

During the next two weeks, Shirley, Lennie and Barbara nursed Lama around the clock. Many students worked continuously. Everyone was very happy to he able to serve Lama. They would feed, clean and massage him. Barbara said she could feel how utterly relaxed Lama was, quite unlike the way an ordinary person would be under the same circumstances, of this she was sure.

Throughout the days, of course, the students with Lama were continuously praying. As were his students around the world; Lama Zopa had given special instructions to all the centers.

Rinpoche discovered that he’d been carrying a Tibetan text on how to deal with paralysis. There were specific prayers and mantras to do in order to protect against more paralysis and reverse what already existed. It explained what food and exercises were suitable. Rinpoche instructed the people looking after Lama to say the mantra, om dumbali dumbali su su shey shey soha, loudly so that Lama could hear it and that they were to get him to repeat it seven times. The text also said that there should not be sparkling sunlight or mirror reflections in the room, so during the daylight hours Lama’s room was kept dim.

Song Rinpoche arrived from Switzerland on February 20th and stayed with Lama for three days. He performed many pujas and gave Lama initiations. By the twenty-sixth, however, three days after Song Rinpoche had left, Lama worsened. He was vomiting continually and was considerably weaker.

At Lama Zopa’s request, Dr. Don Brown, another student of Lama’s, came to examine him. Immediately Don recommended that Lama go to hospital to receive intensive care. He was taken to the Presbyterian Hospital in San Francisco. After tests, it was concluded that Lama must have surgery as soon as his strength could be built up.

It was agreed that neither Stanford nor the Presbyterian Hospital was the place for the necessary heart surgery. After much brainstorming, and observations by Rinpoche, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles was decided upon; this was confirmed by Song Rinpoche in Switzerland.

Meanwhile, Lama’s strength was gradually building up, as he was being intravenously fed. And his paralysis was remarkably improved. Plans went ahead to have him moved to Los Angeles. Max Math—Lama called her ‘Mummy Max’—organized an air ambulance, a helicopter, to take Lama on the five- hundred mile journey south. He was accompanied by a cardiologist, Lennie and Max, and met at the hospital three hours later by long-time student John Schwartz.

He was placed in the coronary care unit. The hospital and Lama’s doctor there, Steven Corde, were incredibly kind. In spite of regulations they allowed people to stay with Lama continuously. Characteristically, Lama treated Dr. Corde as if he were an old, dear friend.

Steven Corde told Rinpoche and Lennie that Lama’s condition was critical, ‘like walking on a cliff.’ But he felt there was hope. Rinpoche asked him what he would do. Dr. Corde explained a procedure for strengthening the heart and prefaced his answer by saying, ‘If he were a member of my own family I would…’ Rinpoche said, ‘Doctor, this is the last hospital we will go to. You seem to understand Lama and his case, so, as you would do for your own family, please you do for Lama.’ And he requested to be informed about any crucial decisions so that he could ‘check up.’

As in all the hospitals, the medical staff were told about the Tibetan Buddhist attitude towards the death process and, as everywhere, Steven Corde and the staff of the Cedars-Sinai were sensitive and understanding.

That night, and the following, March 2nd, the last night of Lama’s life, Rinpoche and Thubten Minimal, a young Sherpa monk from Kopan who had served Lama for years, stayed with Lama. Also with them on the last night was Vajrapani resident, Chuck Thomas.

Chuck spent ten hours with Lama on the eve of his passing. He said Lama was completely conscious, talking and laughing with the nurses. He ate strawberries and talked about those that he grew in his garden. Some of his Los Angeles students visited Lama. They said he was as kind as ever, sending love to everyone.

In the middle of the night Rinpoche sent Chuck out to rest, then to make torma offerings and White Tara pills: Rinpoche intended to offer Lama a White Tara empowerment on the morning of Losar, the Tibetan New Year.

Around three-thirty or four in the morning Lama asked Rinpoche to do the Heruka sadhana with self- initiation with him. Lama was able to sit up for the meditation. Two students in the room as well were reciting White Tara mantras.

The moment Rinpoche had finished the Heruka sadhana Lama’s heart beat changed; it could be observed on the monitor. It beat faster, then slower, and his breathing changed. A nurse came in and asked Lama if he was all right. ‘Yes,’ he said. Was he hurting? ‘No.’

Barely twenty minutes before dawn, at seven minutes past five on the first day of the new year, Lama Yeshe’s heart stopped. Rinpoche immediately checked with Song Rinpoche whether or not to attempt resuscitation; he said yes. A team worked on Lama’s heart for two hours. Steven Corde reported to Lama Zopa that there was no response. Rinpoche asked, ‘Doctor, what is the longest time you have worked on someone after their heart has stopped?’ ‘Three hours,’ he said. Lennie asked if he had had success. ‘No,’ he told her. Rinpoche said, ‘I think it is time to stop.”

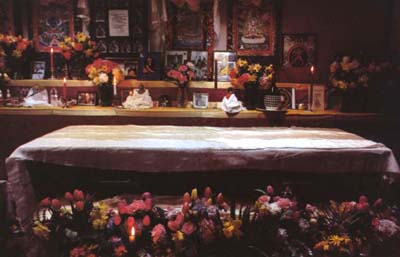

From that point on no one was to touch Lama’s body. Geshe Gyeltsen, who has a center in Los Angeles, arrived at Cedars Sinai. He and Rinpoche performed pujas at Lama’s bedside, and students were told to do Heruka mantras. Meanwhile, a room on another floor was being prepared for Lama’s body.

At eleven o’clock two orderlies gently wheeled Lama’s body, covered in his saffron robes, through the hospital corridors in a silent procession. Rinpoche had permission to keep Lama’s body there till ten in the evening.

Rinpoche and the students set up the quiet corner room as a sanctuary, making an altar on a bedside table and placing blankets on the floor for people to sit comfortably. When things were settled, Rinpoche stood before Lama’s holy body and, with what one student called ‘exquisite devotion,’ made three full length prostrations before sitting.

People sat with Lama throughout the day, always reciting mantras. Just after five-thirty in the evening Rinpoche broke the utter silence in the room by suddenly shouting Heruka mantras. Chuck thought he noticed Lama’s head move slightly under the covering robes, but felt he must have been hallucinating. But Rinpoche bent down to him and said, ‘Now Lama’s meditation is finished.’

Earlier in the day Lennie had made arrangements with a local mortuary, Abbott and Hast—recommended by the hospital as a mortuary that ‘took pride in catering to special-interest, religious and ethnic groups’— to take Lama’s body from the hospital. Mr. Hast was located on a yacht in the Pacific performing a burial at sea.

He was very kind. He arranged from there the appropriate formalities for obtaining permission from the governor’s office to perform the cremation on the Vajrapani land: observations had found that either Vajrapani or Dharamsala would be most suitable.

Although it was a Saturday afternoon there were no hitches: permission was granted and a fire permit issued by the Boulder Creek environmental office, for which someone there graciously offered the two dollar fee.

Lama’s body was moved that night to Mr. Hast’s mortuary. Rinpoche was given special permission to spend the night there. Students who had spent sleepless nights at the hospital were encouraged by Rinpoche to go home. Others came to sit through the night with him and Thubten Monlam.

The room was large with comfortable sofas and pillows and chairs. Lama’s body was at one end of the room and was covered with his saffron robe, a bouquet of white carnations at his feet. The overhead light was dim and the soft flicker of candlelight gave a most serene and peaceful atmosphere. There were hot plates for boiling water, and tea and tsog offerings from the hospital pujas were plentiful. Rinpoche suggested that people make prostrations and recite the practice to the thirty-five buddhas.

During the night, Rinpoche left the room to make phone calls. One was to request Song Rinpoche again to come to California from Switzerland, this time to oversee the cremation of Lama’s body. Later, when he heard that he would come, he smiled and said, ‘It will be good for the students.’ At eleven in the morning of Sunday March 4th Lama Yeshe’s body was taken from the mortuary and driven north to Vajrapani by one of the residents, Tom Waggoner, accompanied by a caravan of cars.

The journey took fourteen hours. At one in the morning of Monday they wound their way slowly up the dark bumpy road from the town of Boulder Creek into the huge redwoods of the retreat center. Residents and retreaters were lining the path to the gompa, and the sounds of conches, bells, damarus and chants, resonating into the night sky, greeted the cars as they approached.

The closed coffin, draped in white offering scarves, was placed by the altar at the front of the gompa, where it would remain until Wednesday afternoon, the eve of the cremation itself.

The news of Lama’s death had started to spread around the world on Saturday morning. Although it was well known that he had been gravely ill, the fact of his death was stunning, almost impossible to take in. An Australian nun said that the last time she saw Lama, in Italy five months before, he had seemed like an old man, needing help to walk and scarcely able to breathe. ‘If it had been any other person of the same age I would have known they were close to death; but somehow, because it was Lama, I just couldn’t, wouldn’t allow my mind to grasp it.’

Venerable Lama Thubten Yeshe

1935-1984

By Monday morning Californian time—Monday night in Europe and Tuesday morning in Australia—the news had hit home. Scores of people, from Australia, New Zealand, India, Nepal, Malaysia, Hong Kong and many European countries, had already arrived or were on their way to Vajrapani .

Already, Geshe Sopa had arrived from Wisconsin and Geshe Thinley, one of Lama Yeshe’s brothers, had come with five others from Australia, where he was resident teacher at Chenrezig Institute. And Kyabje Song Rinpoche was due from Switzerland that night, to officiate at the week-long ceremonies. Also there were Geshe Gyeltsen from Los Angeles, Geshe Lobsang Gyatso, the resident teacher at Vajrapani, and the reincarnation of his teacher from Sera Je, Tenzin Sherab, a young Canadian boy, and Jeffrey Hopkins and Elizabeth Napper from the University of Virginia.

American monk Thubten Pelgye and others had started to organize the kitchen, bringing in food enough to feed one hundred people for a week. And forty-five minutes away, not far from Santa Cruz and Lama Yeshe’s house at Aptos, Peter O’Donnell and the staff of Greenwood Lodge, a conference center and home of the Universal Education Association, had opened up their rooms and cabins to accommodate the visitors.

On Monday night Song Rinpoche was picked up from the San Francisco airport and taken to Lama’s house, where he would stay until Saturday March 11th. There with him were Lama Zopa, Geshe Thinley, Geshe Gyeltsen and Geshe Sopa. They were being looked after by Thubten Monlam, the young Sherpa monk whom Lama had sent for from Kopan a month before, and Lama’s friend, Age Delbanco. By Tuesday afternoon, the gompa was packed. There was a Vajrayogini puja and self-initiation, and in the evening a Heruka Vajrasattva tsog offering written by Lama Yeshe in 1982, with prostrations to the thirty-five Buddhas being performed alternately. As much as possible, Lama Zopa had said, these purification practices should be done—’not for Lama’s sake but for our own.’

People continued to arrive during the week. Although many had not met before, there was a powerful feeling among everyone of deep friendship; brothers and sisters sharing the grief of losing an incredibly loved parent.

Lama Zopa asked Geshe Sopa to talk to the people on Wednesday morning. ‘We have known each other for a long time, as teacher and student, since he was a young boy,’ he said. ‘During these past years Lama Yeshe has done so much beneficial activity for so many people, especially in the West.’

Geshe Sopa emphasized harmony. ‘There are many students everywhere at all the centers that Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa have established. It is so important to be very ‘friendly towards each other, like children of the one spiritual father…We should ask. “How can I help?”‘

Lama Yeshe is gone, but ‘Lama Zopa is still here. His activities everywhere are great, sowing seeds everywhere for the development of this wonderful spiritual teaching that is most beneficial to sentient beings.’

After the talk, an all-day Heruka puja and self-initiation started. And John Jackson and others, with the supervision of Song Rinpoche, began work on the stupa in which Lama’s body would be burned. The site chosen was a clearing on a ridge, five minutes’ walk up from the gompa, which had a spectacular view of miles of forest and the smell of the unseen ocean beyond.

|

|

|

|

|

Keeping vigil at Lama’s body next door was Bill Kane. ‘Beautiful odorous were coming from his body,’ he said. On Wednesday morning he assisted Lama Zopa and others prepare Lama’s body for cremation. It was to be burned in an upright position, so his knees were drawn up to his chest and tied tightly with katas. His arms were crossed and a dorje and bell placed in his hands. He was dressed in his magenta robes and a yellow chogo. Upon his head was placed a triple-tiered black bodhisattva’s hat adorned with a crystal rosary, and his face was covered by a red cloth. His body, in a chair, was driven in procession up to the ridge, which was already prepared for the fire puja.

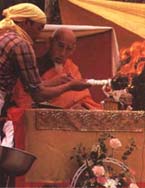

Mountains of appropriate offerings for the fire were on a side altar, between the stupa and Song Rinpoche’s throne. The place was covered in flowers. Incense wafted on the breeze and the sky was bright and blue. Two hundred people were assembled—monks, nuns, lay men and women, and children and included five of Lama Yeshe’s doctors, members of the administration of the University of Santa Cruz where Lama had taught for a term in 1978, and many, many friends. One, a woman who ‘always dresses in red’ had met him five years before and was immediately attracted because of his ‘wonderful laugh.’ That morning she had heard that ‘Lama Yeshe was in town’ so came to Vajrapani with an offering of flowers— only to discover that she was coming to his cremation.

The van carrying Lama’s body stopped at the edge of the crowd. His body was carried to the stupa—only the square base of which, waist high, had been built so far—and carefully placed inside. Metal rods were put horizontally on all sides of the body to keep it upright. Firewood was stacked around him and oil poured over the wood to ensure that the fire would burn well.

The remainder of the stupa was built around Lama’s body. Bricks were laid in a circular fashion to form a cone-shaped structure about eight feet tall. The entire stupa was covered with mud and, as it dried, with white wash. The square base had four openings, one on each side, and the upper part two, for receiving the offerings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The person elected to start the fire had to be someone who had not received teachings from Lama. She prostrated three times in front of the stupa, bent low and, with a burning torch handed to her by one of the attendants, set fire to Lama Yeshe’s body.

The Yamantaka fire puja commenced. The mountain of offerings slowly diminished as the ingredients were handed to Song Rinpoche who in turn handed them to Chuck Thomas and others who offered them to the fire. The puja lasted three hours. Throughout, a deep stillness, a composure, a sense of the unexpressed grief, pervaded. And the only sound to be heard above the chanting was the blazing of the powerful fire.

By one o’clock the puja was over. Later, Song Rinpoche and Lama Zopa returned to the stupa to seal the openings; it would remain untouched until Sunday afternoon when Lama Zopa would dismantle it and remove the relics of Lama’s body.

|

|

|

|

I’m just very numb,’ Lama Zopa said later that afternoon, when he talked briefly in the gompa. ‘I can’t think of anything.’ Rinpoche sat for a full five minutes before continuing. ‘These high lamas, His Holiness and all these high lamas, including Lama Yeshe, they do not fit us, they do not fit. Because of our small merit, they just do not fit. They are like a huge burden that we cannot carry.’ Earlier. he had said that Lama had died ‘because we do not have the merit. But we should not think too much about this because we would go mad. Instead, we should protect our mind and try to practice dharma.’

It seemed that people hung on to his every word. Lama had always been the pillar of strength; now, with him gone, people looked with a sense of relief almost to Lama Zopa. He thanked everyone for their kindness during the past few months. ‘If we follow Lama’s wishes, every piece of advice, if we put it all into practice then I think it will become a quick cause for Lama to reincarnate soon. Maybe he will even come to America! I think that’s all.’ he said. ‘I will pray.’

By Friday, many people had left. In the afternoon Song Rinpoche gave a Heruka Vajrasattva initiation and talked briefly. He, like the other lamas, stressed harmony. ‘We are all very good relatives,’ he said. ‘Loving each other is the most important thing.’

Kyabje Song Rinpoche was bade farewell—for what would be the last time—at the airport on Saturday, when he returned to Switzerland. That night Lama Zopa invited people to Lama’s house for a Lama Choepa puja. The room was packed. The ocean pounded just outside the windows. It was good to be there in that house that Lama had loved. The puja, sung in English, was intense and heartfelt. It was seven days since Lama’s death.

On Sunday afternoon, Lama Zopa went back up to the ridge to open the stupa and remove the relics. He requested that everyone stay in the gompa and recite Vajrasattva mantras and do prostrations. Tenzin Sherab, the young Canadian Rinpoche, was there with Lama Zopa. ‘First we did prayers, then more prayers,’ he said later. ‘We started opening the stupa at exactly two-fifty p.m. and at four-twenty-four we finished taking everything out.

First, the stupa had to be carefully dismantled, brick by brick. Each bone was taken from the stupa floor and handed to Lama Zopa, who would examine it and put it aside in the red trunk bought especially for the relics. The ashes were put separately.

Later, Rinpoche said that the fire had been almost too good; it had burned so fiercely that most of the body had burned completely. What remained, apart from the bones, were part of Lama’s heart and kidneys. ‘I saw every bone in his body,’ Tenzin Sherab said. Later, during the drive down to Santa Cruz, he said that during puja after taking out the relics he looked up into the sky and saw, besides other things, ‘a cloud forming into an arrow and pointing towards the south, and four Tibetan letters, la, la, sa and ra. ‘ Song Rinpoche suggested that these might indicate the name of the mother of Lama Yeshe’s future incarnation.

The relics were carried in procession down to the gompa where again purification practices were done. Rinpoche thanked everyone at the conclusion of the puja. ‘I am completely satisfied. Everything has gone so perfectly, nothing inauspicious has happened.’ He said that even if the pujas had been done by the monasteries in south India, it all could not have gone better. He gave to each person a capsule of ashes — ‘vitamins for the mind,’ he called them.

By Monday afternoon, Vajrapani land had returned to its normal serene routine. The week that had seen one of the most extraordinary events of the centre’s seven years of existence had come and gone like a dream. Lama Zopa had returned to India that morning, via Switzerland where he would see Geshe Rabten and Song Rinpoche, and the people had returned to their homes and centers and monasteries around the world.

Lama’s relics, once consecrated by Song Rinpoche in Switzerland, were divided up and sent to each of the centers, where they were received with great respect and ritual ‘as if you were receiving Lama himself,’ Rinpoche had advised. Most of the relics, however, went to Kopan where eventually they will be sealed inside a larger-than-life-size statue of Lama; the face, an exact likeness, is being made by American sculptor Courtland Bennett, and the body, with the hands in Vajrasattva mudra, by local Nepali artists.

A thousand small statues of Lama Yeshe, commissioned by Max Mathews, are being made in India, and the bulk of the ashes from the cremation will be mixed with clay and made into small Vajrasattva statuettes (tsa-tsa).

In accordance with Lama Yeshe’s own wishes—that a year’s Heruka Vajrasattva retreat be done ‘wherever my body is’—a retreat started at Kopan in April. A yearlong retreat also commenced mid-year in Spain, at the O Sel Ling Retreat Center.

It is possible for people to come to these retreats for any period of time. Most other centers have held or plan to hold shorter retreats at times to suit their students.

While preparing Lama’s body for cremation, Bill Kane asked Rinpoche if Lama had ever indicated to him where he planned to take rebirth. Rinpoche thought for a while before replying that no, Lama had never said any thing about it, but Rinpoche’s own opinion was that Lama ‘had karma with California.’ Seven months later Rinpoche said in a letter to one of his students that in a dream he had seen that ‘Lama had already decided on his rebirth.’

And in December he said, ‘Lama will reincarnate soon. We have done many pujas and have been checking and will continue to check through lamas and deities. So sooner or later we can have big parties for Lama’s reincarnation.’

- Tagged: lama yeshe

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.Realize that the nature of your mind is different from that of the flesh and bone of your physical body. Your mind is like a mirror, reflecting everything without discrimination. If you have understanding-wisdom, you can control the kind of reflection that you allow into the mirror of your mind.