- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

However the very bottom line is to do all ones actions with bodhichitta. That is the best, the most meaningful way to think during your break time. This makes your life most beneficial. As much as possible with awareness keep ones attitude and thoughts in bodhichitta, the thought of benefiting others, try to do all the activities with that mind, including doing your job and throughout the day. This way even in your break time whatever you do becomes the cause of happiness.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

In-depth Stories

23

Rasmus Hougaard, Maitripa College, Portland, Oregon, US, February 2015. Photo by Marc Sakamoto.

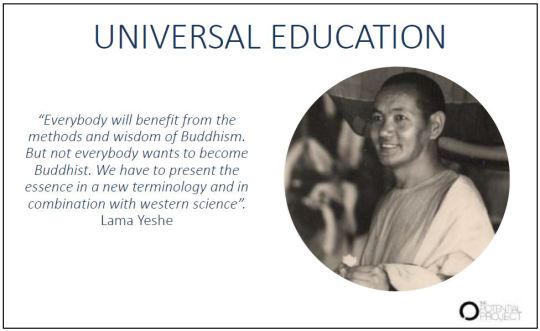

Rasmus Hougaard is the founder and managing director of the Potential Project, an international program based in Copenhagen, Denmark, that works with corporations and organizations to equip their leaders and employees with methods to be more kind, clear-minded, focused and efficient. Active in Europe, Asia, Australia and North America, the Potential Project provides Corporate-Based Mindfulness Training, which is a learning program recognized by the Foundation for Developing Compassion and Wisdom (FDCW), an FPMT-affiliated project devoted to developing and promoting Lama Yeshe’s vision of universal education. Rasmus spoke with Mandala managing editor Laura Miller in February 2015, during a visit to Maitripa College in Portland, Oregon, US.

Laura Miller: Tell me a little about yourself and how you came to start the Potential Project.

Rasmus Hougaard: I’m an FPMT student. I’ve been that for quite a few years and I feel very closely related to Lama Zopa Rinpoche – just as much as through Lama Yeshe’s vision of universal education, which is promoted by FDCW. I have been a director of Tong-nyi Nying-je Ling, the FPMT center in Copenhagen, for a number of years. I have been guiding classes there for many years. I’ve been teaching retreats at FPMT centers around Europe and the world for around the last eight years or so, so I feel very close to FPMT. It is really my family for sure.

Also, I have this very, very strong connection with the whole idea of universal education as Lama Yeshe taught it himself. That really blew my mind when I first heard about it. I joined what would become the FDCW team in London – before it was really a team – when Allison Murdoch was just beginning to start it up years ago. I was part of the first training course on the 16 Guidelines, the trainer training for that and a number of other things.

At some point, I took a year off to figure out how I could create the most benefit in this short lifetime. I came to the conclusion after a year thinking that I should bring “mind training” – what I call “Dharma in disguise” – into other for-profit and non-profit organizations. I had three main reasons for the project. One is because people in those environments need it a lot, because they are very stressed and they need good tools to cope. You can bring them Dharma in a way in which they will embrace it. They won’t go to a Dharma center. Another reason is there is a lot of power in organizations nowadays, so if you can influence them to think more ethically, more compassionately, then there could be a really nice ripple throughout the world, not just in those companies that we would work with. The last one was that everyone needs to be able to make a living off the work that they do, and I just know so many good Dharma students who are working with all kinds of jobs that are fine and good, but where they are not using their best skills of teaching the Dharma. I thought that if we could create a vehicle whereby Dharma teachers could actually join and go and spread the Dharma in disguise in organizations, we would have more happy people, have a better world, and would have income that we could then donate to organizations like Maitripa College or the many other FPMT-related center, projects and services. That is where it all came from – a vision of doing a lot of good in a very focused way.

Laura: What’s the best way to teach mindfulness? Can we get all the potential benefits of developing mindfulness from Dharma practice in the traditional way of studying the texts, meditating and doing the practices? Or does Western science add something to this that helps us integrate it better into our modern lives? What is your perspective on the spectrum of very traditional presentations to very secular?

Rasmus: I think, to make use of the words of the Buddha, the Dharma has “one taste,” and it is the taste of freedom. That taste can be presented in many, many different ways. It could be presented, as you say, very traditionally or very secularly. In my mind, it really doesn’t matter what you do. It is just important that you think about who your audience is, and then do what works for them – skillful means. I am not attached to the secular. I am not attached to the traditional. I am focused on finding ways of delivering the same messages, the same core, the same essence, the same methods, the same wisdom to people in a way that they can relate to it.

In our work at the Potential Project, we go out to people not only who are not interested in Dharma, but they are not necessarily even interested in mindfulness. The organizations pay for us to do the work, but the people signing up for the course haven’t asked for it necessarily. We have to be very, very skillful in presenting mindfulness in a way where they are attracted to it right away and where they find some benefits right away. That is really what I think is very important: look at what the audience needs.

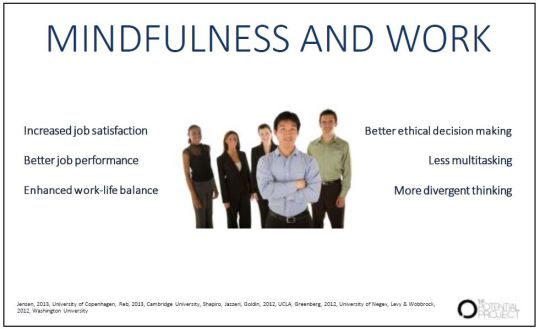

Slide from Potential Project workshop. Courtesy of Rasmus Hougaard.

Laura: When the Potential Project is brought into a company, what do you do? Could you describe the process and the work itself?

Rasmus: In terms of schedule, we do many different things. What we prefer to do is a large “implementation program,” as we call it. This is an 11-workshop program where we come in for 11 sessions spread over four months. Each session is one and a half hours. We are teaching them basically three things. The first thing is the actual mindfulness practice. During the first five weeks, we teach them what in Sanskrit is called shamatha training – stilling the mind – shiné in Tibetan. From there we move into vipassana, or what’s called in Tibetan lhaktong training. We go into the basic philosophy of impermanence, dissatisfaction and emptiness. So that is the foundation of the actual mind training. On top of that, we build a layer of skills that we call “mental strategies,” which are really basic Buddhist principles of patience, compassion, beginner’s mind, acceptance – those basic things that you need to develop in your life if you want not only a happier life, but also a life where you are more in tune with other people and where you can be more effective in your work.

Then the last layer of skills we help develop are specifically designed for the audience we are talking to and is about relating mindfulness to their work. For example, how can you use and how can you develop more focus and more insight in your way of answering and receiving email? How can you develop your mind to be more focused and be more clear and wise in your meetings? How do you do that when setting goals and priorities, when planning your time? So all those practices that we have to do while we are at work, how can we utilize the power of training the mind and how can we train the mind while engaging in those activities?

Laura: What kind of responses do you get from this, and have you seen changes within companies that have done your trainings?

Rasmus: The very short answer is yes, definitely, we’ve seen changes. Before the Potential Project started doing this work, I had been teaching meditation in Dharma centers and I had seen people coming in being very motivated and making good progress over a number of years. When we started going into organizations, I thought I would never experience the same kind of motivation and the same kind of progress. However, I was very surprised to see that the transformation actually went sometimes much faster. You go into a full department and they all together embark on this journey of developing a mind that is clearer, calmer and more kind, and they actually do it during working hours. They start to change their work culture based on these principles. It is almost like a retreat because they are there for 8 or 10 hours every day. They make amazing progress fairly fast.

Laura: I have seen articles critical of bringing mindfulness into corporate situations – basically, the concern is whether ethics and compassion are being left out of mindfulness instruction. I think there is a fear that mindfulness could be used by corporations to become more profitable at the expense of poor people and so forth. I’m sure you have seen these critiques. What are your thoughts about this?

Rasmus: I fully understand the criticism and the whole backlash against mindfulness. I have to be honest, I also sympathize with a large part of it. I don’t want to play holy and say we do everything right, because honestly, I don’t know what is right and what is not right. I have some good ideas and I have been checking with my teachers. I think one of the problems with the very secular mindfulness that we see nowadays is that it is a very, very watered down, stripped down version of the Dharma. I wouldn’t even call it Dharma. It is really a psychological approach to the suffering of samsara, that is, how can you alleviate a bit of distress that you are experiencing. Whether it is unethical or not, I don’t know. If that is unethical, then neuro-linguistic programing and many other things are also unethical. I don’t want to have a standpoint on that. From my point of view, coming from a Dharma background, merely alleviating distress is certainly not what we are interested in. We first of all take the actual practice very seriously. Shamata is not for fun. Shamata is a serious practice. It is hard work. Lhaktong practice, vipassana, is not always fun. It can be very painful. It can be very tough. We don’t try to make it easier; we don’t try to wrap it in a way where it is easier than it is supposed to be.

I think there are two things that should always be there in mindfulness: one is the ethical component and the other one is the compassionate component. Without those two, I think you have lost the essence of mindfulness. Our presentation of mindfulness is coming from Buddhism. You can’t take away from that, and you can’t disregard all of the masters of the past that have said that mindfulness, ethics and compassion go hand-in-hand. You can’t have real mindfulness without having compassion. So it is a big part of our program, although not obviously. We don’t tell our clients, “We teach compassion in our ethical program,” because they would never engage with us. We tell them instead that we are coming with a mindfulness program that will make their employees more effective, more calm, more kind, and then we introduce ideas of compassion once we’re in the door.

Slide from Potential Project workshop. Courtesy of Rasmus Hougaard.

Laura: How do you introduce compassion within the corporate setting?

Rasmus: We work with American Express. We work with Microsoft. We work with Accenture. We work with really hardcore, performing, conservative organizations. How do we introduce compassion? We don’t use the word “compassion” – that’s the first thing. We just call it “kindness.” Everyone can agree to kindness, but compassion is a little bit too fluffy for them.

We work with a global consultancy firm, the leading one in the world, in their Manhattan office in New York. When we had the sessions specifically on kindness, because they had been meditating for five to six weeks by then and because so many new seeds had been planted in their minds, they started seeing kindness as not just a nice idea, but something that would benefit themselves and others, and also as a foundation of their way of doing business. They understood that if they could have a real, kind, compassionate approach to their clients, their clients would probably be happier and also would buy more products from them. They suddenly saw a very virtuous circle: they develop good attitudes within themselves, they serve their clients better, and they receive more business, which is nice for them and nice for everyone, as long as the intention is right.

We find communicating these ideas astonishingly easy because human beings are good beings. We don’t want to be evil and we don’t want to suffer; we want to be happy and we want others to be happy as well. If we just provide the space where people can develop this, we find that it comes very much by itself, although we do help them a bit.

Rasmus Hougaard, Maitripa College, Portland, Oregon, US, February 2015. Photo by Marc Sakamoto.

Laura: Let’s talk about email. (laugh)

Rasmus: (laugh) Emails, yeah.

Laura: Over the last year I’ve gone to a couple meetings – the CPMT meeting in Australia – and I was at the North American Regional Meeting and the Foundation Service Seminar, and for people working within the FPMT organization at Dharma centers or in the International Office, I hear people talking about being overwhelmed by email. It’s something I definitely experience and struggle with. And we also have experiences with misunderstandings and confusion resulting from emails. What kinds of ideas and strategies do you talk about in a Potential Project session concerning email? What is something that I can learn from you today about how to do email better?

Rasmus: This ties into your question about whether we present mindfulness in a traditional Dharma way or in a secular way. For this, I’ll just give a completely, stripped down, secular approach to how can you better harness the potential of your mind in your way of dealing with email.

A fundamental aspect about email is that it is one of the biggest triggers of dopamine in your brain, which scientifically is a way of talking about what is called “attachment” from the Buddhist perspective. We have a strong attachment/aversion relationship with our email. We are very compelled to constantly check it. Most people check their email all the time. The downside of that is that it is stressful and it is very inefficient. You get more stressed because you don’t get enough done. The mind, because of both aversion and attraction, just wants to check email all the time, which we end up doing. The more we do it, the more we get into the habit of doing it. And we get more habitual in terms of attachment and aversion. That is not very useful, so we need to find strategies for pausing and distancing ourselves from this mind.

One is to not check email first thing in the morning. When you wake up in the morning and you have done your practice, you come into the office with an expansive, focused mind. If you started the day writing a very important article or doing another thing that really requires your clarity and focus of mind, you would be very well off. But many of us instead open our email program and immediately are bombarded with all the details and unresolved issues of yesterday; today becomes all the crap from yesterday, basically. Not checking email for the first 15 minutes, maybe 60 minutes, maybe two hours in the morning is a very smart strategy.

Another one that is very important is not to have your email open all the time, because if it is open all the time, it will constantly remind you that there is something that could be triggering some dopamine in your brain. Close down all your digital communication for different periods of times throughout the day. Or, say that from 9 a.m. to 10 a.m. and from 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. are the times when I will be checking my email, and no times else. Those are very basic things. Also, switch off all your alerts, all the bells and whistles and all the notifications. There are many small, very practical things you can do whereby you’ll be more focused and less stressed and actually have a more equanimous, balanced mind because you are not driven by that rush of reading new things all the time. Create less addiction.

Laura: Have you seen the results of that with some of your clients? Could you talk about that a little bit, because it seems very difficult to imagine in a certain sense.

Rasmus: As a disclaimer: people may think that I’m just sitting around in a nice Buddhist setting, that because I come from a Buddhist background I must be a hippie from Denmark, the world’s happiest country. But the Potential Project is an organization with 140 people now. We are in 20 countries. We are very, very busy. I travel all the time. This advice is not coming from someone who is having a very easygoing work life. It can be quite tough, actually.

So what have our clients done? I can give a few examples. Carlsberg, a Danish brewer, with whom we worked with over a year implementing this mindfulness program in their entire organization, ended up switching off their email servers at 6 p.m. and reopening them at 6 a.m. They switched off email activities for 12 hours every day for the reason that they didn’t want people to be spammed with emails into the night instead of being home with their families.

A large insurance company decided on email-free Wednesdays. On Wednesdays, no internal email simply allowed employees to be able to have quality time together and to be able to focus on the important things rather than on a constant stream of email all the time. We see many interesting initiatives to basically develop a more calm and mindful way of working rather than just perpetuating the habit that we are all in nowadays.

Photo: Dreamstime.

Laura: How does someone get involved with the Potential Project? Is there a path to becoming a trainer?

Rasmus: There certainly there is. You can go on our website and find the “Want to join?” section. There is an application form that needs to be filled in and sent to us. We do have quite a few FPMT folks within our organization. Having said that, we have found that it is not enough for people to have a good Dharma background. People also need to have a good meditation background, which is not always the case for everyone having a Dharma background. It is also very important that they have a deep experience of what work life is like in a large organization because we have found that if you don’t have that, you can’t really relate to the reality that people are facing. People can easily perceive you as a little bit flaky and it is not very well received, just as if you were bringing a real business man to talk in a Dharma center. Dharma students maybe wouldn’t relate so well to it because they would rather see a trained Dharma teacher. If you go into an organization, you need to have a corporate appeal that will help them see that you really understand their world.

One thing that is important for me to emphasize is that the work that we are doing could never have been possible without FPMT and without many great Dharma teachers, the real Dharma teachers that have been supporting this for many years, maintain our integrity, keeping the messages really clear that it is Dharma and not just a new psychological model or well-being approach. We touched or reached 25,000 people last year. It is only due to the kindness of all the great teachers of FPMT and other organizations.

Learn more from Rasmus in “The Potential Project and Corporate-Based Midnfulness Training” from Mandala April-June 2014. Find even more about the Potential Project at http://potentialproject.com.

- Tagged: foundation for developing compassion and wisdom, in-depth stories, interview, online feature, potential project, rasmus hougaard, universal education

- 0

16

Memorization: Beneficial Exercise for the Mind

Monks working on memorization at Sera IMI House, Bylakuppe, India, November 2013. Photo by Sandesh Kadur|www.felis.in.

Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter), an American monk who just finished his seventh year of study in Sera Je’s geshe program, is a top memorizer and debater. In August 2013, he was one of 16 from his class of 118 chosen to participate in the rik chung debate held at Sera Je Monastic University in South India, a tradition instituted in the 17th century by Desi Sangye Gyatso, the regent to the Fifth Dalai Lama. In February 2015, Ven. Gache received the top award in the lo gyü chenmo (the Great Memorization Exam) at Sera Je Monastery, having committed to memory 873 pages.

Mandala asked Ven. Gache to discuss the history and role of memorization in monastic education and to share memorization tips to help lay students build their own skills.

In his biography of his teacher, Khedrub Je claims that Lama Tsongkhapa would memorize an astounding 17 folios (34 pages) of Buddhist text per day. Two natural reactions to this statement might be, “Is that even possible? It must be exaggerated,” and “Is that really a constructive use of one’s time and energy?” Without giving direct answers to these questions, I would like to respond first by describing a little bit about the place of memorization in Buddhist practice, both historically and today, and some of its potential benefits.

Ven. Tenzin Gache reciting from memorization during the tsog sag, Sera Je Monastery, India, August 2013. Photo courtesy of Ven. Gache.

Memorization has played a central role in the Buddhism’s saga since its earliest days. For the first few hundred years, the sutras and their commentaries were not written down. Monks and nuns would work together to keep these discourses in memory, orally passing them on to the next generation. In the First Council of Arhats shortly after the Buddha’s passing [also known as the First Buddhist Council, c. 550-450 BCE], his attendant Ananda recited from memory the entirety of the Sutra Pitaka [the collection of sutras], while another monk, Upali, recited the discourses on vinaya [monastic discipline]. Even after these discourses were committed to paper, memorization remained a standard practice in the monasteries and nunneries of India. The great scholar-practitioner Acharya Vasubandhu [c. 4th century CE] is said to have maintained a yearly ritual wherein he would sit upright for several days, gradually reciting all of the texts he had memorized in a bathtub of oil to keep himself awake. More recently, Geshe Rabten [1921-86 CE] observed a similar yearly ritual, but without the oil.

Memorization of the sutras and their commentaries is a standard monastic practice in all Buddhist countries, but here I will focus mainly on its expression in my own monastery, Sera Je, one of the three great Gelug monastic universities now located in South India.

Memorization in the Monastic Curriculum at Sera Je

Memorization is a significant part of a monk’s daily schedule, and mainly serves three purposes: memorizing philosophical texts for debate, memorizing prayers and rituals, and memorizing practical, advice-oriented texts. Each monk is free to choose how much he emphasizes any of these three.

Philosophical Texts

Memorization at Sera Je is an integral part of a greater study program that heavily emphasizes debate. In this context, memorization does not become a mere rote ritual, as a monk is expected to also be able to give a detailed explanation of the meaning of a text and defend his arguments against a barrage of criticism.

The discipline of most khangtsen (monastic colleges, or, houses) requires a monk to rise before dawn and recite new material for at least an hour. When there is no morning debate, many monks will continue until lunchtime. In the evening, monks review this material until close to midnight. During holiday breaks, many monks will stay in “memorization retreat,” reciting full-time.

The best memorizers will memorize entire texts such as Lama Tsongkhapa’s Essence of Eloquence, Haribhadra’s Clear Meaning Commentary, and several of Sera Je’s textbooks composed by Jetsün Chökyi Gyaltsen. Others will focus only on the definitions, divisions and key passages. These texts are often terse and confusing, and will only gradually unfold their meaning through prolonged reflection and debate.

At debate, which can last up to six hours a day, one cannot carry a book, so all debating must be done from memory. Often a monk will initiate a public debate with a quote from a text, prompting the defender to correctly identify the source and context. If he cannot answer, the crowd will yell “Chay!” (“Speak!”) until he can. If he is stuck, the questioner might give a few more words from the quote. Later on in the debate, the questioner is free to give quotes to support his argument, but is expected to recite them from memory. If he simply says, “It says something like this in that text,” he may meet with laughter.

Prayers and Rituals

Pujas and group prayers are a daily complement to the debate program. Monks cannot carry prayer books, so they must recite these prayers from memory as best they can. Before even entering the debate program, one is expected to memorize an 80-page prayer book and recite parts of it in a group before the abbot. The monks most serious about chanting will enter the don zang (good reciter) group, later advancing to kä zang (good voice) and finally to umdze (head chanter). The umdze must have the better part of a thousand pages of material memorized and ready for fast-paced reciting. At the tantric monasteries of Gyuto and Gyume, this second aspect of memorization is more heavily emphasized, and all monks must memorize the liturgy that includes the self-generation and self-empowerment of several tantric deities.

Practical Texts

Memorization of practice-oriented texts is not officially part of the study program, though the monastery does recognize monks who have memorized certain of these texts such as Shantideva’s Entering the Bodhisattva Deeds [also known as Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life], Nagarjuna’s Six-Fold Collection of Reasoning,1 and the Five-Fold Dharma of Maitreya.2 Some monks will recite these texts in their spare time such as when walking to and from debate.

The monastery utilizes various skillful methods to encourage monks to memorize. Written memorization exams on the yearly study material are a standard part of the course syllabus, and monks can also opt to take special memorization exams on entire texts. The lo gyü chenmo, “Great Memorization Exam,” is a yearly tradition in which any monk can come and offer an oral exam of whatever material he has prepared. A monk will bring one or more books and place it before a geshe who will proceed to read passages at random. The candidate must continue reciting where the geshe leaves off. The geshe will continue in this way until he is or isn’t satisfied that the candidate really has the material in memory. A scorekeeper sitting behind the geshe keeps track of how many pages the candidate can offer. Several months later, the study deans announce the total scores, awarding a prize to those with the highest totals.

If a monk has memorized an entire text, he is also eligible to perform tsog sag, “merit accumulation,” where over the course of a month he will gradually, rhythmically recite part of the text before the community during the tea breaks in pujas.

Even after completing the study program, the top scholars must continue to memorize: the gekyö (disciplinarian) must recite the monastery rules and the khenpo (abbot) must recite a variety of long texts such as the sojong (monastic confession) ceremony and its associated sutras.

Benefits of Memorization

One common criticism people raise about memorization is that it is just words. It’s true, they are “just words,” however, the words we say and hear have a powerful effect on how we think, feel and behave. For many of us today, popular songs, movie clips and catchphrases continuously replay themselves in our conscious and unconscious layers of mind, subtly influencing our mood and belief system in ways we may not notice until we try to meditate and find our mind is like Times Square or worse.

Ven. Tenzin Legtsok memorizing at Sera IMI House, India, November 2013. Photo by Sandesh Kadur|www.felis.in.

As the content of popular culture mostly encourages attachment, worry or violence, becoming mindful of what we consume is sound advice for bringing our mind into a more peaceful space. Another method to counter these negative influences is to fill our mind with more constructive pathways. Cultivation of positive mental states like compassion, patience and introspection is essential, and memorizing texts and prayers that encourage these states helps to enhance them and ensure that they become more habitual. In fact, the Tibetan word for meditation, gom, literally means “to habituate.” First we learn something and commit it to memory, then we reflect on it and consider its meaning. Finally, we call it to mind again and again, familiarizing with its message and gradually deepening our understanding.

Vasubandhu explains that the lineage of the Buddha’s teachings is twofold: the teachings of scripture and the teachings of realization. Initially, generating realizations in our mind-stream is difficult, especially if we are strongly conditioned to contrary forms of thought and behavior. However, we can immediately participate in the scriptural lineage if we memorize texts and reflect on their meaning. This will place strong imprints on our mind that will gradually develop into deeper realization. Because past masters have composed and recited these same texts and developed these realizations, the mere words are also thought to carry an energy that will purify and ripen our mind-stream. Much like prostrations and mantra recitation, memorization can be a powerful preliminary practice before more advanced meditation.

Dharmakirti points out that while physical development is limited – even Olympic athletes will reach a limit in how far they can extend their jump – the mind’s potential is limitless. Athletes train the body through exercise. Memorization is an exercise for the mind, and much like a physical one, is something in which we can practice, improve and eventually excel. This process enhances and sharpens the mental faculties, which we can then apply to analysis and meditation. Whereas neuroscientists once believed that the adult brain could not develop new neurons for memory or otherwise change its hard-wiring, advances in past decades have firmly overturned this dogma.3 A significant body of study also suggests that memory training may reduce the risk of dementia in old age.4

Rather than leading to dry, uninspired repetition of old facts, memorizing texts allows a student or teacher to be more fully creative. At debate, a monk who can picture the entire text can form connections and penetrate its layers of meaning, authoritatively dispelling wrong conceptions and groundless assertions. A teacher who can recite relevant quotes and call upon ideas from a variety of sources will impress upon students the profound depths and vast breadth of Buddhism’s scholastic, practical and poetic traditions. Memorization is key element in an immersion into these traditions that will gradually pacify and transform those willing to make the effort.

Watch “Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter) at Rik Chung Ceremony, August 4, 2013″ on YouTube.

Conclusions and Where to Begin

When I was at high school in the United States, a visitor who had memorized Paradise Lost performed for our senior English class. We found the performance impressive, even amusing, but many of us wondered to ourselves why anyone would spend so much time on a seemingly trivial activity. With the advent of calculators and computers, and especially more recently with smartphones and iPads, the art of mental aerobics such as memorization seems obsolete. Why calculate in your head when you have a calculator and why memorize when you have a digital encyclopedia? Similarly, modern Dharma students might ask whether the monastic tradition of memorization is important in Western Dharma centers.

If the value of memorization lay purely in the recollection of specific facts, we would be better off keeping our gadgets. I hope this article has suggested that memorization might mean much more. The intention behind memorization is not to become a warehouse of old facts, but to actively train and develop your cognitive abilities and familiarize yourself with constructive ways of thinking. Many of us read a passage from a Dharma text and think, “I must remember this point,” but how often do we forget our initial insight and inspiration? Through memorizing inspiring texts, we continuously call them to mind, habituating ourselves to the positive attitude they convey. Through memorizing difficult texts, we gradually begin to penetrate their hidden significance, while integrating the message into our being in a way that we can start to feel, “This is a part of me.” If we truly are the summation of what we think and believe, we would be prudent to familiarize with eloquent, uplifting and sagacious sayings rather than much of the superficial relics of pop culture that bombard us if we tune into TV and the internet.

If you are wondering where to begin, a good place to start would be to memorize your daily commitments or the teaching prayers at your local Dharma center. Practically oriented verses like Three Principal Aspect of the Path, Lines of Experience, and 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas are also good for daily recitation. Serious students might consider memorizing the root texts or commentaries they are studying. Young students who start now will build a talent that will increase over time and enhance their development. Older students will help keep their minds sharp and memory fresh. In time, memorization can become an element of Western Dharma practice, just as it has been in Buddhist communities in all times and places.

- Set aside some time each day, preferably early in the morning for new material and late in the evening for re-reciting what you memorized in the morning.

- Sit up straight or gently pace in an open area, preferably somewhere where your recitation won’t disturb others.

- Before memorizing, “warm-up” with recitations like Praise of Manjushri, Prayer to Achieve Inner Kalarupa, and Chanting the Names of Manjushri.

- Start by reciting one half a line. When you can recite this five times without looking at the book, recite the second half. Then recite them together. Then do another line. Then add the two together. Continue in this way, gradually adding to the total, until you finish a verse or a few lines of prose. If you are able, start again with a second verse. Then recite the two together. Over time, you may be able to increase the number of verses you can do in a day

- Once you have something committed to memory, continue to recite it once or more a day until it becomes stable. Then gradually decrease your recitation to once every two days, three days, etc. If you have something very well memorized, you may only need to recite it once a month, but getting to that point will take time.

- During your daily activities, minimize distraction and stimulation, especially loud music. Just as when meditating, keeping your mind clear will enhance your practice sessions.

Some Additional Suggestions (optional):

- Before beginning to memorize something, simply recite it every day for one month.

- When you have memorized something well, stop reciting it for some time. When you start again, it will take a little time to bring it back, but it will become more stable.

- Ask a friend or teacher to examine you on what you have memorized – preparing for an exam can enhance your focus.

Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter) is an American monk living at Sera International Mahayana Institute (IMI) House in Bylakuppe, India, and studying at Sera Je Monastic University. Mandala is looking forward to publishing regular features written by Sera IMI monks about monastic life and practice.

In case you missed last month’s online feature, “Jeffrey Hopkins’ Transmission of Honesty,” you can read it now. If you like Mandala’s online features, consider becoming a Friends of FPMT, which supports our work as well as the education programs of FPMT.

1. Root Wisdom, Finely Woven, Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness, Dispelling Objections, Sixty Stanzas on Reasoning, and Precious Garland.

2. Ornament for Clear Realization, Ornament for the Mahayana Sutras, Differentiating Middle and Extremes, Differentiating Phenomena and Pure Being, and Sublime Continuum.

3. See, for instance, William Skagg’s “New Neurons for New Memories” in Scientific American Mind September/October 2014; or Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz’s excellent The Mind and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force, Harper Perennial, 2002.

4. See “Memory in Old Age Can Be Bolstered” in Scientific American Mind November 2012; and “Promising Strategies for the Prevention of Dementia.”

- Tagged: geshe studies, in-depth stories, memorization, online feature, sera imi house, ven. tenzin gache

- 0

22

Jeffrey Hopkins’ Transmission of Honesty

Professor Jeffrey Hopkins, Maitripa College, Portland, Oregon, United States, September 2011. Photo by Marc Sakamoto.

Dr. Jeffrey Hopkins, now 74, is professor emeritus at the University of Virginia and one of the world’s top scholars of Buddhism. He has published 42 books, acted as His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s translator, and had a long academic career during which he trained many prominent Tibetan Buddhist scholars and translators. He currently leads UMA Institute for Tibetan Studies. Dr. Hopkins has been remarkably open in public about a wide range of matters, such as his initial lack of faith in His Holiness, past-life memories, a near-death experience, his youthful delinquency, his sexuality, and so on.

Donna Lynn Brown interviewed him in December 2014 to find out what lessons his honesty might hold for other Buddhist practitioners.

Dr. Hopkins, what is the source of your frankness? Why are you so open?

I was born in 1940 in Barrington, Rhode Island, and I was in my teens in the 1950s. There was a group of us who were disgusted by the aims that were being presented to us: merely making money and so forth. There was a lot of rebellion that was focused against the dishonesty of society, which gradually in my own mind became a matter of seeking my own integrity. My own integrity meant a great deal to me.

I was part of a juvenile gang that got into difficulty with the law, in the sense of increasingly violent pranks, drinking and so forth. It was a relief when I went to a liberal prep school where students were given a great deal of responsibility for their own governance. Despite all my acting out at my public school, I responded very well in that kind of environment, and got excellent grades, because we were respected as people, which is something I had lacked prior to that. Then, in my first year at Harvard, I read Walden by Henry David Thoreau and I was inspired to leave Harvard for the woods of Vermont. I stayed in a small one-room cabin and read, wrote poetry, walked a lot, dreamt out my recurrent trapped dreams, and I believe at that point, began finding my own integrity. And I kept returning to that kind of life.

I was inspired by Herman Melville’s novel Typee, which is set in the Marquesas, north of Tahiti near the equator, and Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence about the artist Paul Gauguin, who painted in the South Seas. It was 1960 and when Vermont got too cold for the wood heater, I went to the woods in Rhode Island. When that got too cold, I shipped out of New York as a passenger on a freighter to Tahiti. I had gotten used to meditating in Vermont on the lake that was down below, and by gazing off into space. On the freighter I would lie on my back and stare upward, filling my mind with the blueness of the sky. The Pacific Ocean was clean and tremendously calm and I filled my mind with that. I didn’t have a visa for Tahiti and after a while some official noticed this and asked me to leave. I used all but my last $15 to take a seaplane to Hawaii. It was nuts, but it was a search for my own integrity.

You were among the earliest scholars to show respect for Eastern scholars, and acknowledge what you learned from them, rather than claiming that you knew more than your “native informants.” Where did your intellectual honesty come from?

This was related to my attitude of searching. Why would I pretend that what l learned from a Tibetan scholar was something I put together myself? Why would I treat these people as somehow different from myself? I thought it was very important, extremely important, to treat every Tibetan scholar fairly, to give them credit for their part in producing any book. I was criticized for this by other professors in my own field. But it just made more sense to have, say, Lati Rinpoche, be a co-author, than to footnote everything he said. In time, people came to understand what collaboration meant. The old saying of “East is East and West is West” doesn’t carry over to how you treat people on the title page of a book.

Photo courtesy of Donna L. Brown.

By making clear what came from others, you revealed that the Western scholar wasn’t always the final expert. Did other academics criticize you for that?

Yes, they did, and I just chose to ignore it. I spoke recently at the Tsadra Translation & Transmission Conference about singing my own song, and what I meant is that certain priorities needed to be righted, and we would right them by how we acted and what we did. It means acknowledging the help you receive and the roles others play, and if those roles are prominent enough, then the person deserves equal billing as the author or the translator. If I couldn’t have understood the text without somebody informing me of its meaning, then that person has played an equal role in its translation even if they don’t know English, because I couldn’t have translated it otherwise. Not to mention the person’s contribution to the footnotes or the explanation that goes along with the translation. This approach has come to be generally accepted. And then also I wanted to point out that many of the academic concerns that Tibetan and Mongolian scholars have are similar to ours. Both sides can learn from the other, though I don’t like talking about sides. I think we are all more or less in the same soup.

Sometimes in Dharma centers people avoid sharing their real views or feelings. This helps maintain harmony, but at a price. It makes me wonder about the balance between building community and nourishing the individual.

I would compare it to when I started in academia. At that time, there was a lot of shouting among scholars. I thought it had a lot to do with how little we knew about the subjects we were talking about. And I had to admit that of myself also. I was so egregiously, embarrassingly ignorant on many of these topics. I could see how I could stumble into trying to cover up my ignorance by shouting or making a big fuss over something I knew that somebody else didn’t know. And then I tried very hard to avoid doing that, and to create an atmosphere in which I was not doing this. I think as this profession and its members have become more educated, there’s been less need to yell at each other, and this may be true in Dharma centers also. I’ve found in the two translation conferences I’ve been to, and many of these translators are members of Dharma communities, that we have no need at all to shout at each other or show off what we know because we are deeply impressed by what we don’t know. We are really happy to hear about these topics from our colleagues and friends who do know something about them. Then it’s easy to get along.

A community’s insistence on people toeing a line may have a lot to do with being neophytes. And the number of times that neophytes repeat the name of their organization or their lama really strikes me as a sign of weakness. Let’s just stop doing that. Still, within the monastic community, there are rules. Outside of the community, you don’t say nasty things about the community, because that disrupts the image of the community, and spreads gossip and so forth. But that implies that there can be criticism within the community. You’ve got to air differences and so forth. You should. But you can’t be arguing all the time, or sharing everything you think. Nevertheless, a healthy community has to have some way of airing what’s going on. You can’t be covering up all the time because it will explode, and the disharmony that will result from that is not going to be helpful.

On a personal level, I try to make the chance of hypocrisy less by admitting in public some of the things that I’m up to. For example, I gave a talk in a city recently and I was really surprised when the people there gave me some money, in envelopes, afterwards. But then also, at the same time, I was very greedy about that money. I kept wondering how much was in each envelope. And I was very careful to put those envelopes down beside me (laughs) so that nobody would walk off with any of them. And I mentioned it to my host afterwards, admitting how greedy I was about it. I try to make this a habit. I don’t make up stuff to disclose, because there’s plenty of it without making anything up. I may not disclose everything, but at least a whole lot of it. Disclosing it relieves tension, whereas hiding is really counter-productive, because when you hide, you have to simulate the opposite – and, wow, you just get into trouble. I get into trouble!

Professor Jeffrey Hopkins, Maitripa College, Portland, Oregon, United States, September 2011. Photo by Marc Sakamoto.

Is this an aspect of the path? Does not being open reduce energy available for practice?

I think that’s very, very true. Energy is wasted by hiding, and what you are hiding gets worse and worse the more you hide it. It’s self-destructive. You know, sometimes when I talk about morality, I’ll just say, “I’m embarrassed about what I am saying, but in any case, I’m trying to present what the books teach as it’s written, and I’m not claiming that I can actually enact this, I want to be clear.” That makes it a lot easier to talk about it. If it’s compassion and the fact that I get angry in certain situations, then it’s easy for me to talk about what I get angry at and use that as an example. Being frank about myself undermines my own negative reactions.

But we have to be judicious about what we say. We can’t be stupidly open. It’s not easy.

Buddhadharma focused its Winter 2014 issue on abuses of power in Dharma communities. One theme was “no more secrets,” because abuses flourish when people deny, cover up, or ostracize those who speak out. What are your thoughts on this?

I’m not an active member of any group. I’m a member of groups, but from a distance, which gives me a certain safety valve. I don’t give any quarter to lamas and so forth who act contrary to moral codes. To me that’s simply improper. If I’m asked about that person, I just say what I’ve heard, I don’t cover up, or at least I hope I don’t. I’m open about what I’ve heard and I’ll say, “Beware.” Covering up or pretending that seemingly ill behavior is the way great lamas behave – I’m just not going to say that. I think that’s simply wrong.

You have mentioned that your relationship with His Holiness the Dalai Lama is very frank. How open should we be with our lamas?

It depends on what the lama can stand! The lama may not want to hear about it. And then what can you do? You may have to go find some other lama, if that’s what you need. Like with anyone, your friends for example, there are certain subjects that some people don’t want to hear about. Even your closest friend may not want to hear about your stomach troubles. So you don’t talk about it. And how much can anyone stand to hear about your sex life? Or your health problems? Even if you’re at death’s door, five minutes is the max. It’s a bore. You shouldn’t expect more than that.

Westerners seem to value openness more than Tibetans. Is there a cultural difference?

I don’t think Tibetans are different from us. Maybe they are getting away with being secretive about how they are running things here (laughs). They are just getting away with pretending that this is the way that they do it. Tibetans among themselves give each other a hard time. They hold each other to account. Whereas some of them come over here and act as if they are kings or queens. They’ll do whatever they can get away with. You don’t have to let them.

Some Westerners, like you, say they have past life memories. While this may come from a desire to be special, there must be some who really were practitioners in the past. Should people be open about memories if they have them? What about the narcissism factor?

I was faced with this during the five years I was at Geshe Wangyal’s monastery in New Jersey in the early 1960s. People would come to visit and talk about their past lives. They were usually princes and princesses. I was looking forward to the day when someone would come and say they were a garbage collector. It’s something that kept me from telling my own story because I didn’t want to be put in the category that I was putting these people in, which has to do with their own aggrandizing imaginations. With myself, I felt what memories I had were rather ordinary. I had to inspect those few memories to figure out what my so-called status was. I didn’t feel glorious. I had to deduce from a few pieces of information what my status might have been. It took a long time for that to come through. I’m suspicious of people who remember themselves as having been very glorious.

Still, I stay neutral on whether people should talk about memories. Although I’m suspicious, I’m not going to put it down. I know in my case that these are actual memories, so I know that does occur. But I wouldn’t blame anyone for being highly suspicious if I told my own story in any detail. They might think, “The guy’s a nut!” I’ve had that kind of thought with respect to others. But some people have related their stories to me, and their memories are not self-glorifying. I don’t have any reason to question them. I do accept for sure that people remember.

Dr. Ian Stevenson of the University of Virginia looked into a lot of reincarnation stories, and checked some against facts he could track down. One of the points that he made was that quite a number of people remembered their past lives because they died in the midst of violence. It was quite often not a case of great spiritual attainment, but that there was some violence that impressed on them what was going on, and that caused the memory.

Canadian tulku Elijah Ary has been open since childhood about his past life memories and went through a lot of difficulties.

I know Elijah Ary. I find his story quite poignant. He and I had quite opposite trails. He has been open throughout and I’ve been closed throughout. I actually forgot it for quite a while and then even after I remembered, it was decades later that I was willing to talk about it at all except with a couple of people. It’s been quite a journey for him, and I really respect what he’s had to go through to be this open. He paid a huge price. For me, coming out as gay was a big step at the time I did it, but coming out as remembering your past life, as far as I’m concerned, is much larger than that.

Professor Jeffrey Hopkins, Maitripa College, Portland, Oregon, United States, September 2011. Photo by Marc Sakamoto.

What does it really tell us if someone has past life memories? Does that make them special now?

I think that Dr. Ian Stevenson’s story about people remembering because they died in the midst of violence indicates that it doesn’t automatically make you special. What will make you special is what you do in this lifetime. If you think about it, that is true of anybody, recognized or not.

Liushar Thupten Tharpa, who was the equivalent of foreign minister in the old government of Tibet, went out to greet His Holiness the Dalai Lama when he first came to Lhasa; Liushar told me he was watching the little child to see if this was the right one. But he didn’t come to any conclusion then whether this was the right or the wrong child. Later he was this Dalai Lama’s representative in New York, after which he came to our monastery in New Jersey, and then stayed on in the USA as a permanent resident. Then the Dalai Lama called him back to Dharamsala. There were a number of years during which Liushar had not seen this Dalai Lama in action on the home front, although he had visited India for important events. Anyway, after he went back to India, I saw him. He said, “Do you know what he is doing?” and he recounted to me how busy this Dalai Lama was conducting ordination ceremonies, teaching, giving initiations, all of the many things he was doing. And he said, “Now we can say he is the incarnation of Avalokiteshvara.” You see? By way of his actions! That question about whether there were signs that he was the last Dalai Lama was totally wiped out. It didn’t matter. His Holiness’ actions were sufficient. Whether he was or not didn’t make any difference because in his waking day he was endlessly performing these actions.

While you are open about many things, you also choose to keep certain things private, such as your own attainments, and ways you’ve helped others – for example, with their books or academic work.

There’s a tradition about not being open about your own attainments and your own deeper experiences, and I don’t even tell my friends. It’s out of the question, I feel, that I’m going to talk about these things. As for helping others, it’s important to do – and keep quiet.

Any final thoughts on honesty?

If honesty became one’s only watchword, one could become a pain in the ass, and narcissistic, and a total bore. I hope by giving an interview like this, pretending to be honest, I don’t create a trap for myself! That I would become infatuated with this – really. And start deliberately acting this way, thinking, “I’ve got to be honest! I’ve got to find something to be honest about!” And turning myself into not just a 25- or 50-percent jerk but a 75- or 90-percent jerk (laughs). Warn me if I do. Tap me on the shoulder and say, “Hey Jeffrey, you are turning into a 100-percent jerk.”

We are basically incapable of saying who we are, and when we start doing that, we really have to be careful, because we aren’t going to be right. There may be some grain of truth – but also some grain of foppishness. I’m trying. I’m still trying to find my own integrity.

“Jeffrey Hopkins’ Transmission of Honesty” was produced as an online feature by Mandala Publications, and is supported, in part, by programs like Friends of FPMT.

Donna Lynn Brown is a regular Mandala contributor and a student at Maitripa College in Portland, Oregon, US.

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.One of the hallmarks of Buddhism is that you can’t say that everybody should do this, everybody should be like that; it depends on the individual.