- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

If we want to understand how we are ordinarily misled by our false projections and how we break free from their influence, it is helpful to think of the analogy of our dream experiences. When we wake up in the morning, where are all the people we were just dreaming about? Where did they come from? And where did they go? Are they real or not?

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom

16

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Defeating the Eight Worldly Dharmas

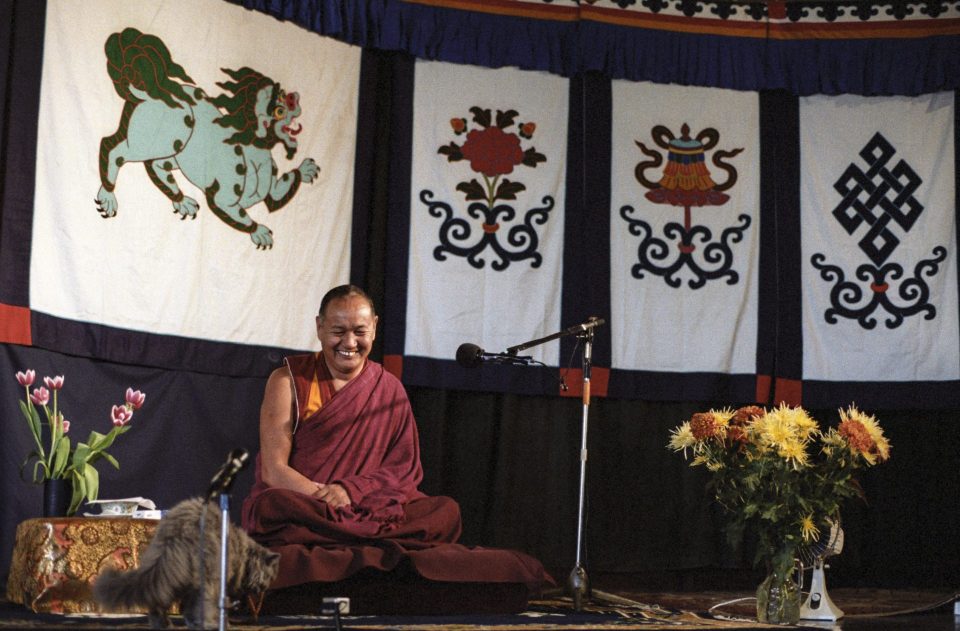

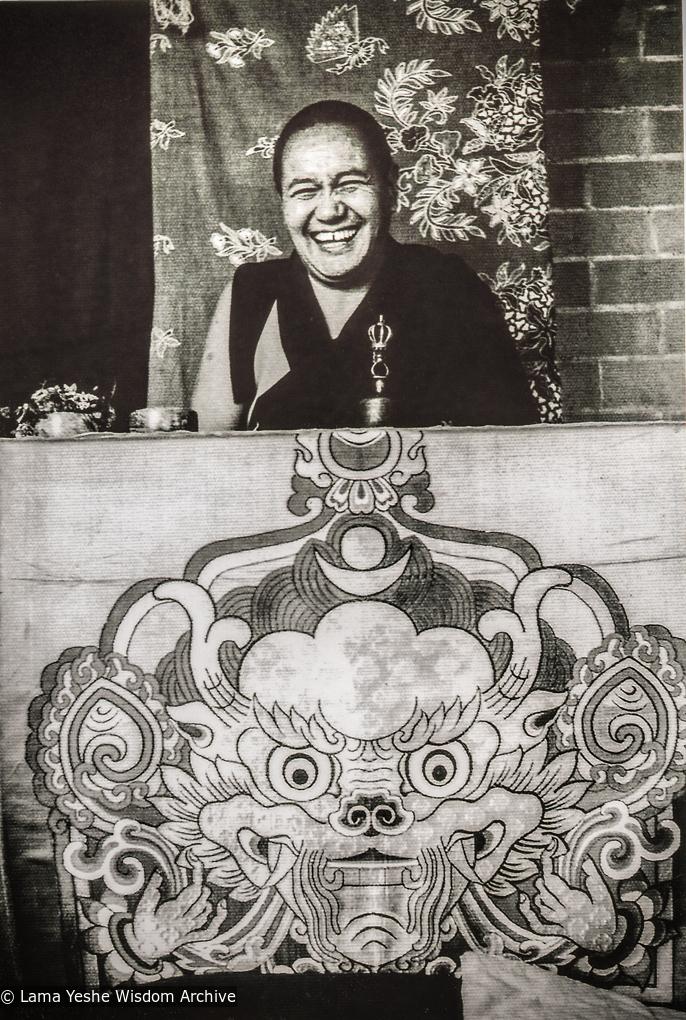

Lama Yeshe teaching at Kosmos Centre, Amsterdam, 1980. Jan-Paul Kool (photographer) Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind is the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings, forthcoming in May 2025 from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. This book contains introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

Here we share an excerpt of Lama Yeshe’s teaching from Chapter 13 of this book, Defeating the Eight Worldly Dharmas:

The attitude behind the eight worldly dharmas, or phenomena, is a symptom of ignorance and ego and we have to recognize it as a negative motivation. For example, if you have the attitude that receiving a present is a source of pleasure and not receiving one is a cause of unhappiness, that’s not good. That attitude is a symptom of ego.

First of all, this attitude does not understand what is a gift and what is not. It functions at a very gross level. You don’t understand the broad view that the gift of other sentient beings is profound. If you think that giving chocolate is the only way to interpret giving—if you’re not giving chocolate, you’re not giving—your view is extremely narrow, and that’s a problem.

Another of the eight worldly dharmas is being attached to pleasant feelings and averse to unpleasant ones. That’s not good either. For a start, the way in which you interpret pleasant and unpleasant is completely relative; it depends. For example, one person considers meditating to be like going to a nightclub or the beach and finds it really enjoyable, while another considers it to be like being in prison and completely miserable. So, finding certain situations pleasant or unpleasant depends on your attitude.

Secondly, taking responsibility for your own liberation and enlightenment is not an easy job. It requires much effort. To demonstrate this, Shakyamuni himself spent six years in indestructible single-pointed meditation without food or other necessities in order to attain his goal. That’s not to say you should punish yourself in that way, but it’s a matter of putting right livelihood into the right channel, skillfully putting your body, speech and mind in the right direction, from peaceful environment to peaceful environment, which is, in fact, the path to enlightenment.

I say that following the path to enlightenment is not an easy job because our wrong conception mind, our grasping attitude, always overwhelms, interrupts and interferes with our efforts, and dealing with all this disruption can be difficult. So we should expect to encounter obstacles when trying to follow the path.

Nevertheless, the Buddhist interpretation of negotiating the path to enlightenment is not that it should be a miserable experience. We should not think, “I’m a religious person, therefore I should suffer; I’m a religious person, therefore I should not have plenty of bread and butter and should feel guilty if I do. Look at the people in Africa; they don’t even have water.” That sort of ridiculous thinking just makes you depressed. Also, it’s not right. You should not make yourself emotionally irritated, confused or guilty. That simply disturbs your tranquility and peace of mind. Read more of Chapter 13, Defeating the Eight Worldly Dharmas.

From Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind, the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings containing introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Subscribe to the LYWA monthly e-letter and keep up with the latest news and ordering information.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: advice from lama yeshe, lama yeshe

28

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Meditation is Action

Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind is the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings, forthcoming in May 2025 from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. This book contains introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

Here we share an excerpt of Lama Yeshe’s teaching from Chapter 1 of this book, Mind and Meditation:

Meditation is Action

If you cultivate your mind in meditation, it becomes sharp and clean clear and you can easily see your false conceptions. This is extremely difficult to do when you are deeply submerged in hallucination, just as it’s extremely difficult to surface when you’re trapped deep in the ocean. At the beginning, when you’re full of wrong conceptions and garbage thoughts, it’s hard to distinguish between right and wrong. Extremely difficult. Therefore, meditation is so worthwhile. Its result is that it integrates your mind and allows you to understand your own actions, which mostly arise from misconceptions and lead you into a restless state of mind.

Through meditation you can also see your great potential and understand that there’s no value in just living for food and clothing. It’s so sad to see people living only for food and clothing, ignoring their great potential. That’s incredibly sad, isn’t it? Living for such small temporal pleasures, which have no real value and do not last. Sometimes, if we really check up, we’re too much; it’s incredible.

What we need to do is to compare the worldly pleasures that our wrong conceptions believe will make us happy with the benefits of meditation. In the West we have hundreds, even thousands, of ideas of what makes us happy, not just food and clothing. Look at supermarket shelves. There are so many ideas. Most of them are wrong conceptions. Through meditation you can discover those temporal objects have little value; actually, no value. I don’t mean you should completely reject them. Don’t reject them, but if you strongly desire them and put too much energy into them, it’s just not worth the effort. Especially when it comes to material objects, which are so unreliable. When you need them, they’re not there; when you don’t, they are. Sometimes they’re there, sometimes they’re not.

Consider medicines, for example. They are there to help us, to support and sustain life, but we can never be sure whether they’ll destroy our life or preserve it. It’s not certain. Through meditation, however, we can discover joy and the everlasting, peaceful state of mind, and that understanding can last forever—from this life to the next and to all our future lives. By comparison, material things can disappear in a flash, and at the time of death we leave everything behind. Not only that; we die with great attachment to our material possessions, and that brings us much harm. It’s not the material objects that harm us but our clinging to and grasping at them. During our life we grasp at this, we grasp at that, building up our attachment more and more, so that when we die, our grasping is incredibly strong and very difficult to release. During our lifetime, our desire wants more and more, such that we build up more and more superstition, which makes us more restless, more confused, more foggy and more ignorant. Therefore, actualizing meditation is really worthwhile.

If you don’t contrast material things with meditation you won’t understand how much more worthwhile the results of meditation are compared with those of the desires of the sense world. If you don’t know that, you won’t have much energy for meditation. Being unsure, you won’t see that sitting down to meditate is of much greater value than running out for chocolate. Your attraction to chocolate will be stronger than your desire for meditation. It’s obvious.

I’m not joking when I talk this way. I’m saying “chocolate,” but I’m referring to the incredibly overpowering Western vibration for sense pleasures. It’s all so exaggerated, which just makes life much more difficult for Western people. So much clinging. I can see that. But at the same time, you people are very intelligent; you can see how shopkeepers and television advertisers in the West understand people’s psychology. Ask yourself, “Why are they doing this? Why are they doing that?” They’re appealing to people’s superstitions and delusions. You can see. Maybe you think I’m exaggerating but check up for yourselves. That is the really important point. Read more of Chapter 1: Mind and Meditation.

From Clean-Clear: Refuge, Bodhicitta and the Nature of the Mind, the second volume in a series of Lama Yeshe’s collected teachings containing introductory teachings given in England in 1976 and Holland in 1980. Compiled and edited by Nick Ribush.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Subscribe to the LYWA monthly e-letter and keep up with the latest news and ordering information.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: advice from lama yeshe

18

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: First Teaching of Intro to Tantra

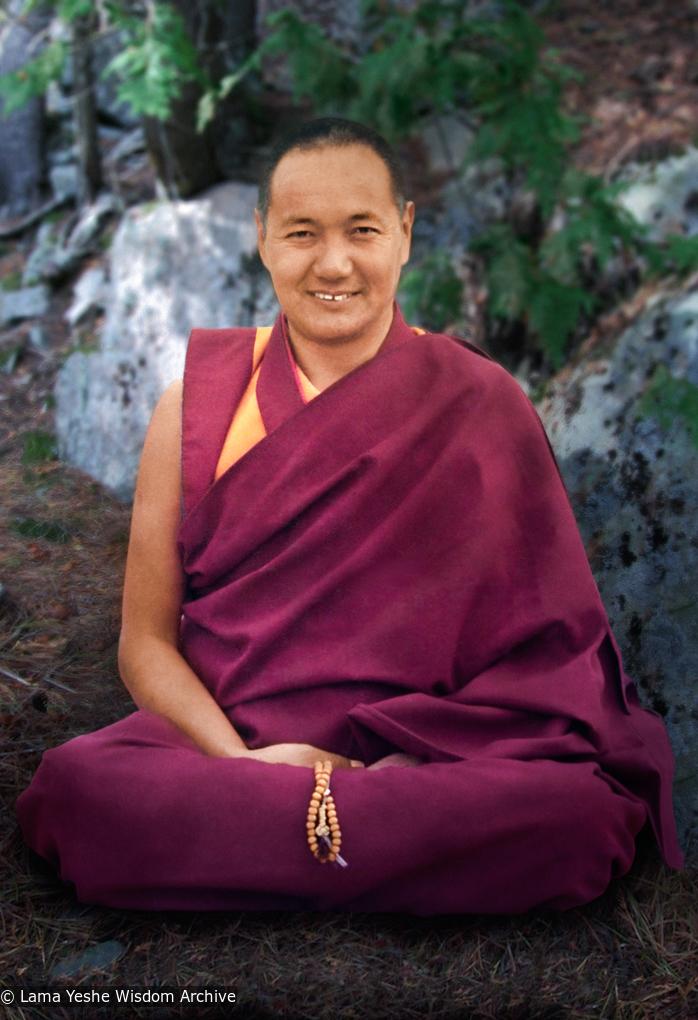

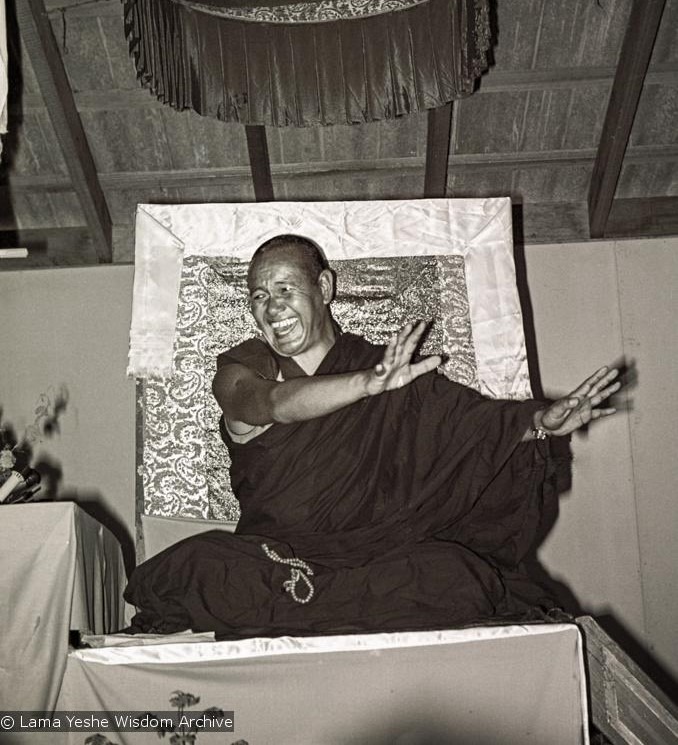

Lama Yeshe, Chenrezig Institute, Australia, 1975. Photo by Tony Duff, retouching by David Zinn. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Lama Yeshe gave a commentary to the Avalokiteshvara (Chenrezig) yoga method at Grizzly Lodge, California, in May 1980. Here we share Lama’s introduction to this series, Intro to Tantra: First Teaching, which constitutes a wonderful explanation of the fundamentals of tantric practice. Please read an excerpt:

Philosophically, perhaps we can say that karma is overwhelming-consciously and unconsciously. Don’t think that karma is just your doing something consciously and then ending up miserable. Karma also functions at the unconscious level. You can do something unconsciously and it can still lead to a big result. Today’s problems in the Middle East are a good example. That’s karma. They started off small, but those little actions have brought a huge result. As a matter of fact, that’s karma.

In order to have the enlightened attitude, an attitude that transcends the self-pitying thought, you need the tremendous energy of renunciation of temporary pleasure-renunciation of samsara. I think you know this already. What do we renounce? Samsara. Therefore, we call it renunciation of samsara. Now I’m sure you’re getting scared! Renunciation of samsara is the right attitude. The wrong attitude is that which is opposite to renunciation.

You probably think, “Oh, that’s too difficult.” It’s not difficult. You do have renunciation. How many times do you reject certain situations, unpleasant situations? That’s you renouncing. Birds and dogs have renunciation. Children have renunciation-if they want to do something for which they’ll get punished, they know how to get around it. That’s their way of renunciation. But all that is not renunciation of samsara. Perhaps your heart is broken because of some trouble with a friend so you change your relationship. Anyway, your friend has already given you up so you have to do the same thing and renounce your friend. Neither is that renunciation of samsara.

Perhaps you’re having trouble coping with society so you escape into the bush, like an animal. You’re renouncing something, but that’s not renunciation of samsara.

What, then, is renunciation of samsara? Be careful now-it’s not being obsessed with the objects of samsaric existence or with nirvana, either. Perhaps some people will think, “Now that I’m not concerned with pleasure, now that I’m renounced, I would like to have pain.” That, too, is not renunciation of samsara. Renouncing the sense pleasures of the desire realm and looking for something else instead, grasping at the pleasures of the form or formless realms, is still the same old samsaric trip.

Say you’re practicing meditation, Buddhist philosophy and so forth and somebody tells you, “What you’re doing is garbage; nobody in this country understands those things.” If somebody puts the nail of criticism into you like that and you react by getting agitated and angry, it means that your trip of Buddhism, meditation or whatever is also samsaric. It has nothing to do with renunciation of samsara. That’s a problem, isn’t it? You’re practicing meditation, Buddhism; you think Buddha is special, but when somebody says, “Buddha is not special,” you get shocked. That means you’re not free; you’re clinging. You have not put your mind into the right atmosphere. There’s still something wrong in your mind.

So, renunciation of samsara is not easy. For you, at the moment, it’s only words, but the thing is that renunciation of samsara is the mind that deeply renounces, or is deeply detached from, all existent phenomena. You think what I’m talking about is only an idea, but in order for the human mind to be healthy, you should not have the neurotic symptom of grasping at any object whatsoever, be it pleasure or suffering. Then, relaxation will be there; that is relaxation. You don’t have superstition pumping you up. We should all have healthy minds by eliminating all objects that obsess the ego. All objects. We are so concrete that even when we come to Buddhism or meditation, they also become concrete. We have to break our concrete preconceptions, and that can only be done by the clean clear mind.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read this full teaching.

A video of Lame Yeshe giving this entire teaching is available:

This teaching is included in Lama Yeshe’s book The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. You can also view the talks on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive YouTube channel, listen to the audio book, or read the book online.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: advice from lama yeshe, lama yeshe

26

Lama Zopa Rinpoche Discussing the Qualities of Lama Yeshe

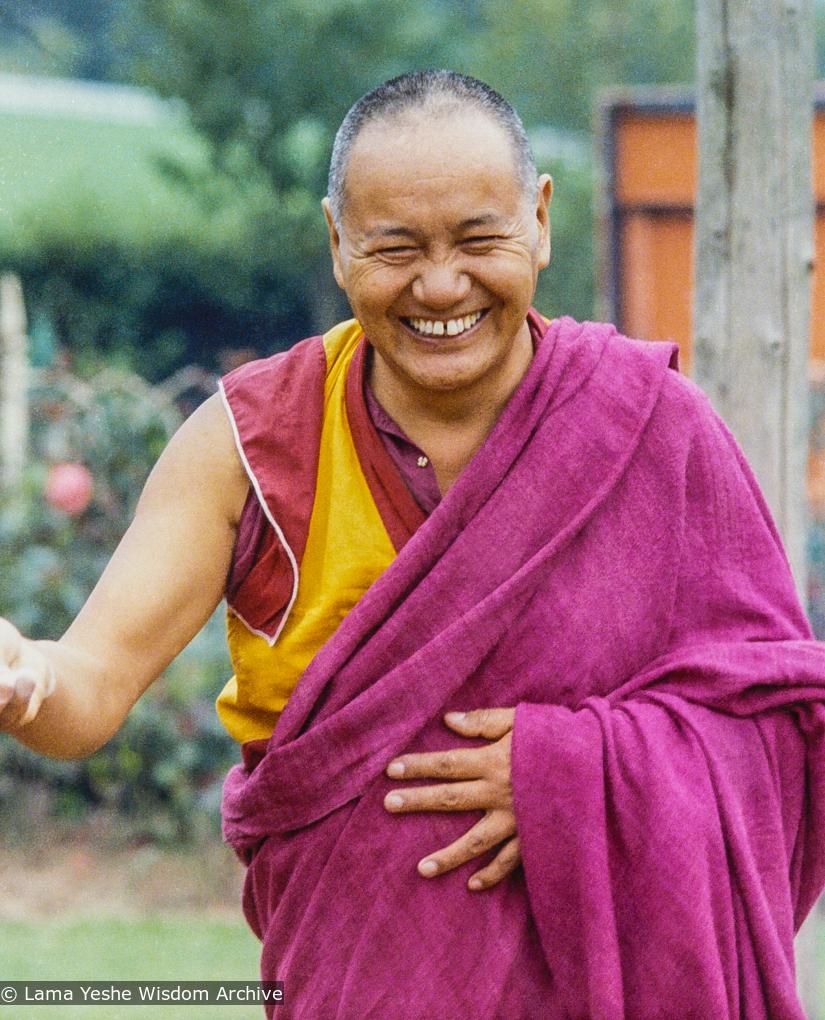

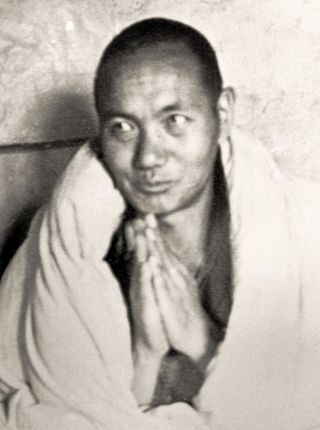

Portrait of Lama Yeshe, Manjushri Institute, England,1982. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Tibetan New Year, Losar, falls on February 28 this year. For FPMT students, this day has additional significance as it commemorates the anniversary of the parinirvana of Lama Thubten Yeshe, who co-founded FPMT with Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Lama Yeshe’s heart stopped beating just before dawn on Losar, March 3, 1984. He was forty-nine years old. In 1959, Lama Yeshe fled the Chinese Communists in Tibet, going into exile in India. He survived tremendous hardship living as a refugee monk in Buxa Duar, where Lama Zopa Rinpoche became his heart disciple. In 1967, the two lamas began teaching Western students, leading to the establishment and flourishing of Kopan Monastery in Nepal and the FPMT organization throughout the world.

As part of Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s advice on how to celebrate Losar and the Fifteen Days of Miracles, Rinpoche recommended sharing stories and remembrances about Lama Yeshe. Here Rinpoche discusses the qualities of Lama Yeshe during a teaching given at Kopan Monastery in 2009:

Lama Yeshe was kinder than all the three times’ buddhas. For the tantric meditators, when you bring the wind into the central channel, the in-breath and out-breath are equalized, without one being stronger than the other. When the wind abides in the central channel the belly does not move; it stays calm. There’s no breathing through the nostrils during the absorption when the gross mind stops and only the most subtle mind is actualized.

That meditation on emptiness is like an atomic bomb, the quickest way to cease the defilements and achieve enlightenment. That becomes the direct cause of the dharmakaya. My guess is that when the mind becomes extremely subtle, when the gross mind stops, at that time the heart stops beating, there is no rising or falling of the belly and no breathing through the nose. I’m not sure; that’s just my guess.

Externally, what Lama Yeshe manifested was a heart problem. That’s what people saw; that’s what the doctors diagnosed it as. Lama actually used this heart problem that outside people saw for his meditation session. Lama’s meditation sessions were often Lama lying down and people took that to be him resting or sleeping; that was the view of other people. Actually, for Lama Yeshe that was a meditation session. It was a very high tantric meditation, part of the completion stage practice, the practice of clear light and the illusory body, the direct cause of the dharmakaya and the rupakaya. He did this at night and always after lunch. To other people he was resting or sleeping, but it was actually a meditation session.

Lama didn’t show much sitting in a formal meditation posture with eyes closed and so forth. He did sometimes, later, but it wasn’t normal for him. He was a very high yogi, a very accomplished master, so his way of doing this was kind of secret. That is what was happening internally.

Outside, whoever he was with, he fitted in with them. If he was with children, he fitted in with them; when he was with old people he fitted in with them. Whoever came he fitted in with them, acting in a way that was best for them, in order to make everybody happy. Therefore, everybody saw Lama differently. Some people even saw him as a big businessman. But in reality he was a great meditator who had realizations of emptiness and bodhichitta. He realized emptiness while still in Tibet. He said he realized emptiness while they were debating Madhyamaka philosophy many years ago in Tibet. And I remember something happened while we were in Delhi and Lama said he could never get angry at even one sentient being, he could never renounce even one sentient being. That shows he had the realization of bodhichitta a long time ago.

I pushed Lama to come to Kopan to help with the course. Usually I talked about the eight worldly dharmas and the negative attitude and the lower realms, and I’d spend about two weeks or so on that, then everybody got very depressed, by hearing all the negatives. Then Lama Yeshe came and made them laugh, releasing them from that sadness and depression. This is how we did it.

Excerpted from The Path to Ultimate Happiness, teachings given by Lama Zopa Rinpoche during the forty-second Kopan lamrim course in 2009 at Kopan Monastery, Nepal, lightly edited by Gordon McDougall and Sandra Smith, and published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: lama yeshe, losar

12

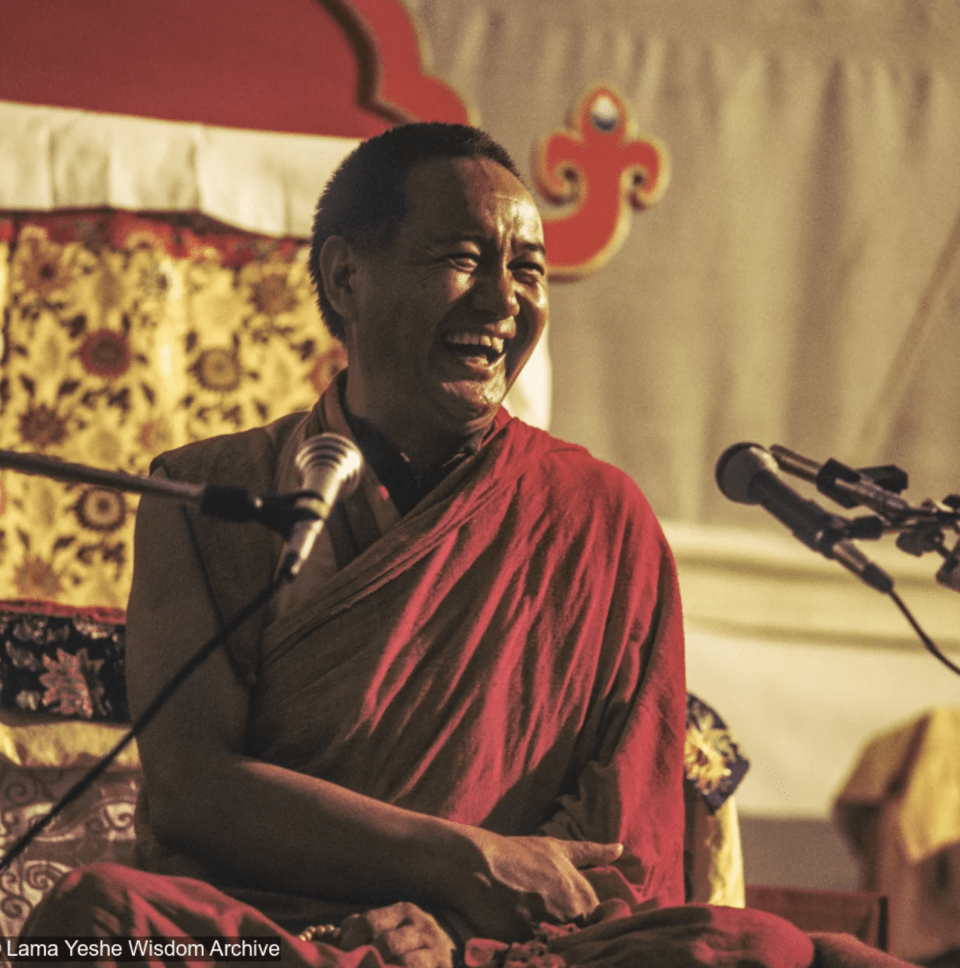

Lama Yeshe teaching at Institut Vajra Yogini, Marzens, France, 1982. Photo taken by T.Y. (Thubten Yeshe), courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism is a book from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive consisting of two teachings from Lama Yeshe. The first, The Three Principal Aspects of the Path, was given in France in 1982. The second teaching, Introduction to Tantra, was given at Grizzly Lodge, California, in 1980. Edited by Nicholas Ribush.

During His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s 1982 teachings at Institut Vajra Yogini, France, Lama Yeshe was asked to “baby-sit” the audience for a couple of days when His Holiness manifested illness. The result is this excellent two-part introduction to the path to enlightenment, in which Lama explains renunciation, bodhicitta and the right view of emptiness. Please read an excerpt from Part 2 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path by Lama Yeshe and watch a precious video of Lama giving this teaching at the end of the excerpt.

Good afternoon. Again, unfortunately, I have to come here and talk nonsense to you. However, I heard that His Holiness is feeling much better this afternoon.

This morning I spoke very generally on the subjects of renunciation and bodhicitta. Now, this time, I will talk about the wisdom of shunyata.

From the Buddhist point of view, having renunciation of samsara and loving kindness bodhicitta alone is not enough to cut the root of the ego or the root of the dualistic mind. By meditating on and practicing loving kindness bodhicitta, you can eliminate gross attachment and feelings of craving, but the root of craving desire and attachment are ego and the dualistic mind. Therefore, without understanding shunyata, or non-duality, it is not possible to cut the root of human problems.

It’s like this example: if you have some boiling water and put cold water or ice into it, the boiling water calms down, but you haven’t totally extinguished the water’s potential to boil.

For example, all of us have a certain degree of loving kindness in our relationships, but many times our loving kindness is a mixture—half white, half black. This is very important. Many times we start with a white, loving kindness motivation but then slowly, slowly it gets mixed up with “black magic” love. Our love starts with pure motivation but as time passes, negative minds arise and our love becomes mixed with black love, dark love. It begins at first as white love but then transforms into black magic love.

I want you to understand that this is due to a lack of wisdom—your not having the penetrative wisdom to go beyond your relative projection. You can see that that’s why even religious motivations and religious actions become a mundane trip when you lack penetrative wisdom. That’s why Buddhism does not have a good feeling towards fanatical, or emotional, love. Many Westerners project, “Buddhism has no love.” Actually, love has nothing to do with emotional expression. The emotional expression of love is so gross; so gross—not refined. Buddhism has tremendous concern for, or understanding of, the needs of both the object and the subject, and in this way, loving kindness becomes an antidote to the selfish attitude.

Western religions also place tremendous emphasis on love and compassion but they do not emphasize wisdom. Understanding wisdom is the path to liberation, so you have to gain it.

Now, as far as emotion is concerned, I think for the Western world, emotion is a big thing, for some reason. However, when we react to or relate with the sense world, we should somehow learn to go the middle way.

When I was in Spain with His Holiness, we visited a monastery and met a Christian monk who had vowed to stay in an isolated place. His Holiness asked him a question, something like, “How do you feel when you experience signs of happy or unhappy things coming to you?” The monk said something like, “Happy is not necessarily happy; bad is not necessarily bad; good is not necessarily good.” I was astonished; I was very happy. “In the world, bad is not too bad; good is not too good.” To my small understanding, that was wisdom. We should all learn from that.

Ask yourself whether or not you can do this. Can you experience things the way this monk did or not? For me, this monk’s experience was great. I don’t care whether he’s enlightened or not. All I care is that he had this fantastic experience. It was helpful for his life; I’m sure he was blissful. Anyway, all worldly pleasures and bad experiences are so transitory—knowing their transitory nature, their relative nature, their conventional nature, makes you free.

The person who has some understanding of shunyata will have exactly the same experiences as that priest had. The person sees that bad and good are relative; they exist for only the conditioned mind and are not absolute qualities. The characteristic of ego is to project such fantasy notions onto yourself and others—this is the main root of problems. You then react emotionally and hold as concrete your pleasure and your pain.

You can observe right now how your ego mind interprets yourself, how your self-image is simply a projection of your ego. You can check right now. It’s worth checking. The way you check has nothing to do with the sensory mind, your sense consciousness. Close your eyes and check right now. It’s a simple question—you don’t need to query the past or the future—just ask yourself right now, “How does my mind imagine myself?”

[Meditation]You don’t need to search for the absolute. It’s enough to just ask about your conventional self.

[Meditation]Understanding your conventional mind and the way it projects your own self-image is the key to realizing shunyata. In this way you break down the gross concepts of ego and eradicate the self-pitying image of yourself.

[Meditation]By eliminating the self-pitying imagination of ego, you go beyond fear. All fear and other self-pitying emotions come from holding a self-pitying image of yourself.

[Meditation]You can also see how you feel that yesterday’s self-pitying image of yourself still exists today. It’s wrong.

[Meditation]Thinking, “I’m a very bad person today because I was angry yesterday, I was angry last year,” is also wrong, because you are still holding today an angry, self-pitying image from the past. You are not angry today. If that logic were correct, then Shakyamuni Buddha would also be bad, because when he was on earth, he had a hundred wives but was still dissatisfied!

Our ego holds a permanent concept of our ordinary self all the time—this year, last year, the year before: “I’m a bad person; me, me, me, me, me, me.” From the Buddhist point of view, that’s wrong. If you hold that kind of concept throughout your lifetime—you become a bad person because you interpret yourself as a bad person.

Therefore, your ego’s interpretation is unreasonable. It has nothing whatsoever to do with reality. And because your ego holds onto such a self-existent I, attachment begins.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read Part 2 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path in its entirety.

We are so pleased to share a video of Lama Yeshe offering this teaching:

This talk is included in Lama Yeshe’s book The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism. You can also view the talks on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive YouTube channel, listen to the audio book, or read the book online.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: essence of tibetan buddhism, lama yeshe

15

Lama Yeshe teaching at Institut Vajra Yogini, Marzens, France, 1982. Photo taken by T.Y. (Thubten Yeshe), courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism is a book from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive consisting of two teachings from Lama Yeshe. The first, The Three Principal Aspects of the Path, was given in France in 1982. The second teaching, Introduction to Tantra, was given at Grizzly Lodge, California, in 1980. Edited by Nicholas Ribush.

During His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s 1982 teachings at Institut Vajra Yogini, France, Lama Yeshe was asked to “baby-sit” the audience for a couple of days when His Holiness manifested illness. The result is this excellent two-part introduction to the path to enlightenment, in which Lama explains renunciation, bodhicitta and the right view of emptiness. Please read an excerpt from Part 1 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path by Lama Yeshe and watch a precious video of Lama giving this teaching at the end of the excerpt.

First of all, all of us consider that we would like to be free from ego mind and the bondage of samsara. But what binds us to samsara and makes us unhappy is not having renunciation. Now, what is renunciation? What makes us renounced?

The reason we are unhappy is because we have extreme craving for sense objects, samsaric objects, and we grasp at them. We are seeking to solve our problems but we are not seeking in the right place. The right place is our own ego grasping; we have to loosen that tightness, that’s all.

According to the Buddhist point of view, monks and nuns are supposed to hold renunciation vows. The meaning of monks and nuns renouncing the world is that they have less craving for and grasping at sense objects. But you cannot say that they have already given up samsara, because monks and nuns still have stomachs! The thing is that the English word “renounce” is linguistically tricky. You can say that monks and nuns renounce their stomachs, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they actually throw their stomachs away.

So, I want you to understand that renouncing sensory pleasure doesn’t mean throwing nice things away. Even if you do, it doesn’t mean you have renounced them. Renunciation is a totally inner experience. Renunciation of samsara does not mean you throw samsara away because your body and your nose are samsara. How can you throw your nose away? Your mind and body are samsara—well, at least mine are. So I cannot throw them away. Therefore, renunciation means less craving; it means being more reasonable instead of putting too much psychological pressure on yourself and acting crazy.

The important point for us to know, then, is that we should have less grasping at sense pleasures, because most of the time our grasping at and craving desire for worldly pleasure does not give us satisfaction. That is the main point. It leads to more dissatisfaction and to psychologically crazier reactions. That is the main point.

If you have the wisdom and method to handle objects of the five senses perfectly such that they do not bring negative reactions, it’s all right for you to touch them. And, as human beings, we should be capable of judging for ourselves how far we can go into the experience of sense pleasure without getting mixed up and confused. We should judge for ourselves; it is completely up to individual experience. It’s like French wine—some people cannot take it at all. Even though they would like to, the constitution of their nervous system doesn’t allow it. But other people can take a little; others can take a bit more; some can take a lot.

So, I want you to understand why Buddhist scriptures completely forbid monks and nuns from drinking wine. It is not because wine is bad; grapes are bad. Grapes and vines are beautiful; the color of red wine is fantastic. But because we are ordinary beginners on the path to liberation, we can easily get caught up in negative energy. That’s the reason. It is not that wine itself is bad. This is a good example for renunciation.

Who was the great Indian saint who drank wine? Do you remember that story? I don’t recall who it was, but this saint went into a bar and drank and drank until the bartender finally asked him, “How are you going to pay?” The saint replied, “I’ll pay when the sun sets.” But the sun didn’t set and the saint just kept on drinking. The bartender wanted his money but somehow he controlled the sunset. These kinds of higher realization—we can call them miraculous or esoteric realizations—are beyond the comprehension of ordinary people like us, but this saint was able to control the sun and drank perhaps thirty gallons of wine. And he didn’t even have to make pipi!

Now, my point is that renunciation of samsara is not only the business of monks and nuns. Whoever is seeking liberation or enlightenment needs renunciation of samsara. If you check your own life, your own daily experiences, you will see that you are caught up in small pleasures—we [Buddhists] consider such grasping to be a tremendous hang-up and not of much value. However, the Western way of thinking—”I should have the best; the biggest”—is similar to our Buddhist attitude that we should have the best, most lasting, perfect pleasure rather than spending our lives fighting for the pleasure of a glass of wine.

Therefore, the grasping attitude and useless actions have to be abandoned and things that make your life meaningful and liberated have to be actualized.

But I don’t want you to understand only the philosophical point of view. We are capable of examining our own minds and comprehending what kind of mind brings everyday problems and is not worthwhile, both objectively and subjectively. This is the way that meditation allows us to correct our attitudes and actions. Don’t think, “My attitudes and actions come from my previous karma, therefore I can’t do anything.” That’s a misunderstanding of karma. Don’t think, “I am powerless.” Human beings do have power. We have the power to change our lifestyles, change our attitudes, change our habits. We can call that capacity Buddha potential, God potential or whatever you want to call it. That’s why Buddhism is simple. It is a universal teaching that can be understood by all people, religious or non-religious.

The opposite of renunciation of samsara—to put what I’m saying another way—is the extreme mind that we have most of the time: the grasping, craving mind that gives us an overestimated projection of objects, which has nothing to with the reality of those objects.

However, I want you to understand that Buddhism is not saying that objects have no beauty whatsoever. They do have beauty—a flower has a certain beauty, but that beauty is only conventional, or relative. The craving mind, however, projects onto an object something that is beyond the relative level, which has nothing to do with that object, that hypnotizes us. That mind is hallucinating, deluded and holding the wrong entity.

Without intensive observation or introspective wisdom, we cannot discover this. For that reason, Buddhist meditation includes checking. We call checking in this way analytical meditation. It involves logic; it involves philosophy. So Buddhist philosophy and psychology help us see things better. Therefore, analytical meditation is a scientific way of analyzing our own experience.

Finally, I also want you to understand that monks and nuns may not be renounced at all. It’s true, isn’t it? In Buddhism, we talk about superficial structure and universal structure. So when we say monks and nuns renounce, it means we’re trying, that’s all. Westerners sometimes think monks and nuns are holy. We’re not holy; we’re just trying. That’s reasonable. Don’t overestimate again, on that. Lay people, monks and nuns—we’re all members of the Buddhist community. We should understand each other well and then let go; leave things as they are. It’s unhealthy to have overestimated expectations of each other.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read Part 1 of The Three Principal Aspects of the Path in its entirety.

We are so pleased to share a video of Lama Yeshe offering this teaching:

This talk is included in Lama Yeshe’s bookThe Essence of Tibetan Buddhism. You can also view the talks on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive YouTube channel, listen to the audio book, or read the book online.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

24

Lama Yeshe at Kopan Monastery, 1971. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Around Christmas time between 1971 and 1975, Lama Yeshe gave several talks related to Christmas to the Western students at Kopan Monastery, Nepal, in case some of them were missing their families and being at home at that festive time of year. These talks, and another given on Christmas Day, 1982, at Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa during Lama’s teachings on the Six Yogas of Naropa, have been collected into the book Silent Mind Holy Mind. So many years later, we share these precious teachings this time of year with students new and old who can benefit from Lama’s timeless advice. We also share our best wishes to all for the observation of Lama Tsongkhapa Day, which falls this year on December 25, Christmas Day.

Below we share an excerpt from Chapter 4 of Silent Mind, Holy Mind, which is from a talk given by Lama Yeshe in 1982 at Istituto Lama Tzong Khapa in Pomaia, Italy. We are also so pleased to share a video of this teaching:

Christmas, 1982

By Lama Yeshe

Somehow, we’re still alive and aware enough to remember how long it is since Jesus was born. It was one thousand, nine hundred and eighty-two years ago, right? And I myself am fortunate enough to have been born in the Shangri-la of Tibet, to have come into contact with the world of Western dakas and dakinis, and to have this chance to acknowledge the history of the holy guru, Jesus.

I’ve found that having a little understanding of Jesus’s life helps me develop my own path, but it’s not easy to fully understand the profound events in Jesus’s life. It’s quite difficult. Of course, the superficial events of his life are fairly easy to understand, but there’s not enough room in our mind to comprehend his high bodhisattva actions. Even when Lord Jesus and Lord Buddha were here on earth it was very difficult for ordinary people to understand who they really were. At that time, very few people understood.

Today I was looking at the Bible, at the Gospel of John in particular, and he was talking about the miracles Jesus performed and how few people understood the profundity of his liberated mind that allowed him to perform those miracles.

Anyway, whenever I’m at a meditation course such as this at Christmas time, I like to talk about this kind of thing. But you need to understand that when I do, I’m not trying to be diplomatic. I don’t need to negotiate my relationship with you in that way. It’s just that from the bottom of my heart, I sincerely feel and believe that simply to remember Jesus’s life is an incredible opportunity.

In a way, of course, it doesn’t matter where people come from— East or West—or what color they are, those who eliminate their self-cherishing thought and give their life for others are exceptional human beings. For that reason, I’m happy just to bring Jesus to mind and reflect on what he did.

Also, to some extent I’m responsible for my Western students’ psychological wellbeing, so if we’re going to bring Buddhism to the West, we need to do it in a healthy way rather than introduce it as some exotic new trip. We don’t need new trips—we need to do something constructive, something worthwhile. Anything truly worthwhile does not diminish any light; it only enhances it.

And with respect to psychological health, we’re part of the environment and the environment is part of us. Therefore, those of us who were born in the West should not reject the Christian environment into which we were born. We should consider ourselves lucky to have been born into a Christian society and to have the wisdom to understand what that means for our mind. Such understanding is very useful if we’re to remain healthy. Especially these days, when there’s dangerous revolutionary technology everywhere and the world is overwhelmed with fighting and war, we really need to actively remember the lives of our unselfish historical predecessors.

So, John was explaining how God sent Jesus to us as a witness to the truth, but most unfortunately, some ignorant people failed to recognize who he was or understand what he was teaching and killed him. In my opinion, the Buddhist point of view is that Jesus was a bodhisattva, not only in the sense that he had realized bodhicitta and overcome selfishness, but in the sense that, as a performer of miracles, he was a saint, like Tilopa and Naropa or, to name a living example, His Holiness Zong Rinpoche—somebody completely free of superstition who sometimes instinctively does strange things that the rest of us don’t understand.

For example, John says that one day Jesus was near the water when a woman came by to fill her pot. Jesus said to her, “How can you satisfy your thirst with water? It’s water that makes you thirsty in the first place.” He told her that since it’s water that makes her thirsty, how can water be the solution to her thirst. It’s some kind of reverse thinking. Who can understand that? It sounds crazy, doesn’t it?

What he meant was that only spiritual water can truly slake your thirst. So you can see, the actual meaning is somehow beyond words. The woman’s taking water; he says, “Why are you doing that? It’s not going to solve your problem of being thirsty.” It’s crazy talk. Nowadays we’d probably hit somebody who spoke to us like that. But luckily, back then Jesus didn’t get beaten up for talking in that way.

John also said that since Jesus was born from God, his disciples were also derived from God’s energy. That’s similar to what the Buddhist teachings say when they explain that all shravakas and pratyekabuddhas are born from Shakyamuni Buddha. The sense here is that such followers are born from the teacher’s wisdom truth speech. Through internalizing that, they discover the truth for themselves and become such realized beings.

Philosophically, of course, we can say that Buddhism doesn’t accept that God is the source of all human beings and other things. But from another point of view, we can say that Buddhism doesn’t contradict that statement either. For example, where does the human realm come from? The Buddha said that the human realm is caused by good karma. That’s true. If the upper realms do not come from good karma, then where do they come from? Then, from the Buddhist point of view, all good karma comes from the Buddha…or, you can say, God. Therefore, the human realm comes from God, from Buddha. Because of the Buddha’s holy speech, sentient beings create good karma. I want you to be clean clear about this.

Still, philosophically you can argue this point one way or the other. It depends on how you interpret it. You can interpret the statement negatively or positively. Actually, you can do anything with philosophy.

Now, concerning God, what is the different between Buddha and God? Today, I’m going to say that according to Buddhism and

Christianity, the qualities of the Buddha and the qualities of God are the same. People always worry about creation. “God is the creator of everything; Buddha is the creator of everything.” Does that mean the Buddha created negativity? Well, the Buddha said that ultimately, there’s no positive, there’s no negative.

Tibetans address this issue with the example of a river. When you’re standing on one bank of the river you call the opposite bank “the other side.” When you’re on that bank you call this one “the other side.” There’s this side and that side, that side and this side. It’s interdependent. Without each other, this side and that side wouldn’t exist. In the same way, if positive doesn’t exist, negative

can’t exist either. In other words, negative comes from positive, positive comes from negative.

Then maybe you’re going to argue, “Well, if God is the creator, if God is the cause of everything, such as organic things like plants, then how can God be permanent?” People say God is permanent—then how can something that’s permanent produce

something impermanent, like a plant? The principal cause of an impermanent phenomenon has to also be impermanent.

That sort of argument comes from Buddhists, so I’m going to debate with them: “Then how can you say shravakas and pratyekabuddhas are born from Buddha? Buddha is permanent.” The answer to that is that such statements are not meant to be taken literally. In response to that, I’m going to say, “Well, God can be the same as Buddha, in the sense of a personal being. God can be a person in the same way Shakyamuni Buddha was.” It’s not as if a permanent God is sitting up there somewhere. God can be something organic, a personal being with whom you can personally relate.

I tell you, philosophers always try to make everything very special. “God. Buddha. God is this; Buddha is that.” They put God and Buddha up on some kind of untouchable pedestal, so ordinary people can’t relate to them. They make it impossible to understand the nature of God, the nature of Buddha. That’s stupid. They just create more obstacles for people.

Then human beings, with their limited minds, try to put cream on God, chocolate on God, like with a knife. They put their own garbage on God. That’s all wrong; definitely wrong. I truly believe that sometimes philosophy can become an obstacle to people really understanding the nature of God or Buddha. Maybe I’m a revolutionary, but I reject many of the philosophical positions on these matters.

However, personifying God or Buddha doesn’t contradict their omnipresent nature. We can talk about the personal qualities of Heruka, for example, but at the same time, he is universal and omnipresent. We need to understand that.

Excerpted from Silent Mind, Holy Mind, Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive, 2024, edited by Jon Landaw and Nicholas Ribush.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

- Tagged: silent mind holy mind

5

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Follow Your Path Without Attachment

Lama Yeshe teaching at Les Bayards, Switzerland, 1975. Photo by Barbara Vautier, courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind one of the most beloved free books from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. The six teachings contained in this volume come from Lama Yeshe’s 1975 visit to Australia. They are all filled with love, insight, wisdom and compassion, and accessible question-and-answer sessions.

Please enjoy Chapter 6 of The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “Follow Your Path Without Attachment” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at Chinese Buddhist Society, Sydney, AUS, April 24, 1975. Edited by Nicholas Ribush:

Those who practice meditation or religion should not cling with attachment to any idea.

Fixed ideas are not external phenomena. Our minds often grasp at things that sound good, but this can be extremely dangerous. We too easily accept things we hear as good: “Oh, meditation is very good.” Of course, meditation is good if you understand what it is and practice it correctly; you can definitely find answers to life’s questions. What I’m saying is that whatever you do in the realm of philosophy, doctrine or religion, don’t cling to the ideas; don’t be attached to your path.

Again, I’m not talking about external objects; I’m talking about inner, psychological phenomena. I’m talking about developing a healthy mind, developing what Buddhism calls indestructible understanding-wisdom.

Some people enjoy their meditation and the satisfaction it brings but at the same time cling strongly to the intellectual idea of it: “Oh, meditation is so perfect for me. It’s the best thing in the world. I’m getting results. I’m so happy!” But how do they react if somebody puts their practice down? If they don’t get upset, that’s fantastic. It shows that they are doing their religious or meditation practice properly.

Similarly, you might have tremendous devotion to God or Buddha or something based on deep understanding and great experience and be one hundred percent sure of what you’re doing, but if you have even slight attachment to your ideas, if someone says, “You’re devoted to Buddha? Buddha’s a pig!” or “You believe in God? God’s worse than a dog!” you’re going to completely freak out. Words can’t make Buddha a pig or God a dog, but still, your attachment, your idealistic mind totally freaks: “Oh, I’m so hurt! How dare you say things like that?”

No matter what anybody says—Buddha is good, Buddha is bad—the absolutely indestructible characteristic nature of the Buddha remains untouched. Nobody can enhance or decrease its value. It’s exactly the same when people tell you you’re good or bad; irrespective of what they say, you remain the same. Others’ words can’t change your reality. Therefore, why do you go up and down when people praise or criticize you? It’s because of your attachment; your clinging mind; your fixed ideas. Make sure you’re clear about this.

Check up. It’s very interesting. Check your psychology. How do you respond if somebody tells you your whole path is wrong? If you truly understand the nature of your mind, you will never react to that kind of thing, but if you don’t understand your own psychology, if you hallucinate and are easily hurt, you will quickly find your peace of mind disturbed. They’re only words, ideas, but you’re so easily upset.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read the rest of this chapter along with a question and answer session.

Excerpted from Chapter 6 of Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “Follow Your Path Without Attachment” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at Chinese Buddhist Society, Sydney, AUS, April 24, 1975, published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. You can read this book online, listen to the audiobook, access links to translations or download a PDF. LYWA Members can download the ebook for free.

You can also order a paperback copy from Amazon’s print-on-demand service. Go to the Amazon website in your region to find the best price for a print-on-demand copy.

Lama Thubten Yeshe (1935–1984), who founded the FPMT organization with Lama Zopa Rinpoche, was able to translate Tibetan Buddhist teachings into clear ideas that resonated with the Western students he met and taught in the 1970s and ’80s.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

6

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: An Introduction to Meditation

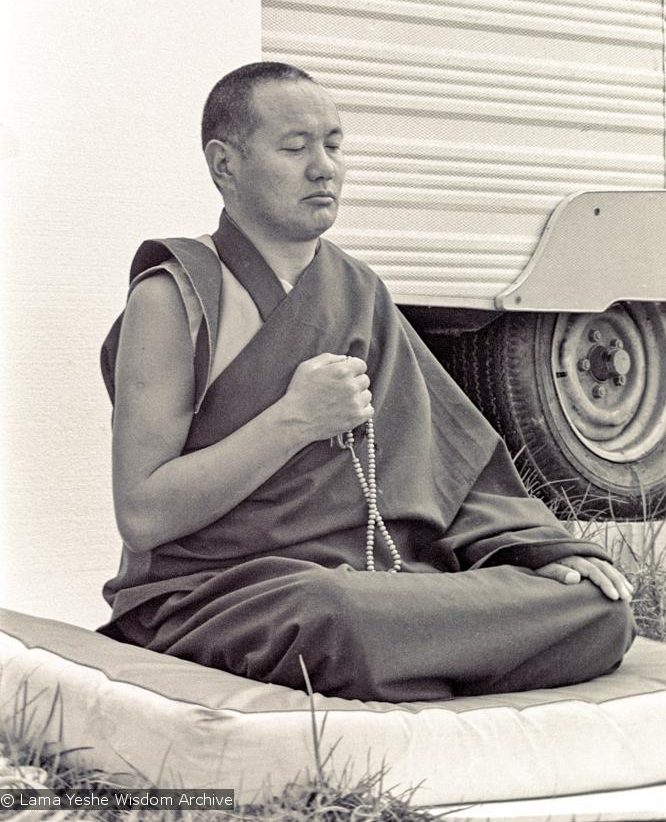

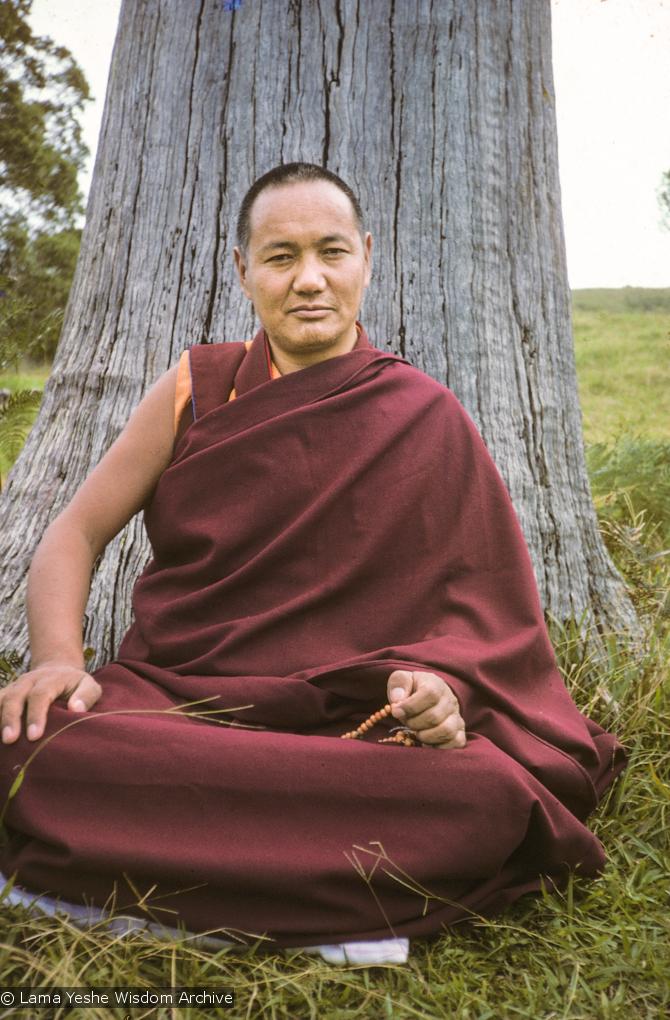

Lama Yeshe meditating during a month-long course at Chenrezig Institute, Australia, 1975. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind one of the most beloved free books from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. The six teachings contained in this volume come from Lama Yeshe’s 1975 visit to Australia. They are all filled with love, insight, wisdom and compassion, and accessible question-and-answer sessions.

Please enjoy Chapter 5 of The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “An Introduction to Meditation” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at Anzac House, Sydney, AUS, April 8, 1975. Edited by Nicholas Ribush:

From the beginning of human evolution on this planet, people have tried their best to be happy and enjoy life. During this time, they have developed an incredible number of different methods in pursuit of these goals. Among these methods we find different interests, different jobs, different technologies and different religions. From the manufacture of the tiniest piece of candy to the most sophisticated spaceship, the underlying motivation is to find happiness. People don’t do these things for nothing. Anyway, we’re all familiar with the course of human history; beneath it all is the constant pursuit of happiness.

However—and Buddhist philosophy is extremely clear on this—no matter how much progress you make in material development, you’ll never find lasting happiness and satisfaction; it’s impossible. Lord Buddha stated this quite categorically. It’s impossible to find happiness and satisfaction through material means alone.

When Lord Buddha made this statement, he wasn’t just putting out some kind of theory as an intellectual skeptic. He had learned this through his own experience. He tried it all: “Maybe this will make me happy; maybe that will make me happy; maybe this other thing will make me happy.” He tried it all, came to a conclusion and then outlined his philosophy. None of his teachings are dry, intellectual theories.

Of course, we know that modern technological advances can solve physical problems, like broken bones and bodily pain. Lord Buddha would never say these methods are ridiculous, that we don’t need doctors or medicine. He was never extreme in that way.

However, any sensation that we feel, painful or pleasurable, is extremely transitory. We know this through our own experience; it’s not just theory. We’ve been experiencing the ups and downs of physical existence ever since we were born. Sometimes we’re weak; sometimes we’re strong. It always changes. But while modern medicine can definitely help alleviate physical ailments, it will never be able to cure the dissatisfied, undisciplined mind. No medicine known can bring satisfaction.

Physical matter is impermanent in nature. It’s transitory; it never lasts. Therefore, trying to feed desire and satisfy the dissatisfied mind with something that’s constantly changing is hopeless, impossible. There’s no way to satisfy the uncontrolled, undisciplined mind through material means.

In order to do this, we need meditation. Meditation is the right medicine for the uncontrolled, undisciplined mind. Meditation is the way to perfect satisfaction. The uncontrolled mind is by nature sick; dissatisfaction is a form of mental illness. What’s the right antidote to that? It’s knowledge-wisdom; understanding the nature of psychological phenomena; knowing how the internal world functions. Many people understand how machinery operates but they have no idea about the mind; very few people understand how their psychological world works. Knowledge-wisdom is the medicine that brings that understanding.

Every religion promotes the morality of not stealing, not telling lies and so forth. Fundamentally, most religions try to lead their followers to lasting satisfaction. What is the Buddhist approach to stopping this kind of uncontrolled behavior? Buddhism doesn’t just tell you that engaging in negative actions is bad; Buddhism explains how and why it’s bad for you to do such things. Just telling you something’s bad doesn’t stop you from doing it. It’s still just an idea. You have to put those ideas into action.

How do you put religious ideas into action? If there were no method for putting ideas into action, no understanding of how the mind works, you might think, “It’s bad to do these things; I’m a bad person,” but you still wouldn’t be able to control yourself; you wouldn’t be able to stop yourself from doing negative actions. You can’t control your mind simply by saying, “I want to control my mind.” That’s impossible. But there is a psychologically effective method for actualizing ideas. It’s meditation.

The most important thing about religion is not the theory, the good ideas. They don’t bring much change into your life. What you need to know is how to relate those ideas to your life, how to put them into action. The key to this is knowledge-wisdom. With knowledge-wisdom, change comes naturally; you don’t have to squeeze, push or pump yourself. The undisciplined, uncontrolled mind comes naturally; therefore, so should its antidote, control.

As I said, if you live in an industrialized society, you know how mechanical things operate. But if you try to apply that knowledge to your spiritual practice and make radical changes to your mind and behavior, you’ll get into trouble. You can’t change your mind as quickly as you can material things.

When you meditate, you make a penetrative investigation into the nature of your own psyche to understand the phenomena of your internal world. By gradually developing your meditation technique, you become more and more familiar with how your mind works, the nature of dissatisfaction and so forth and begin to be able to solve your own problems.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read the rest of this chapter.

Excerpted from Chapter 5 of The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “An Introduction to Meditation” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at Anzac House, Sydney, AUS, April 8, 1975, published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. You can read this book online, listen to the audiobook, access links to translations or download a PDF. LYWA Members can download the ebook for free.

You can also order a paperback copy from Amazon’s print-on-demand service. Go to the Amazon website in your region to find the best price for a print-on-demand copy.

Lama Thubten Yeshe (1935–1984), who founded the FPMT organization with Lama Zopa Rinpoche, was able to translate Tibetan Buddhist teachings into clear ideas that resonated with the Western students he met and taught in the 1970s and ’80s.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

16

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Attitude is More Important than Action

Lama Yeshe teaching at Chenrezig Institute, Australia, 1975. Photo by Wendy Finster, courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind is one of the most beloved free books from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. The six teachings contained in this volume come from Lama Yeshe’s 1975 visit to Australia. They are all filled with love, insight, wisdom and compassion, and accessible question-and-answer sessions.

Please enjoy Chapter 4 of Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “Attitude is More Important than Action,” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at the Theosophical Society, Adyar Theatre, Sydney, Australia, April 7, 1975. Edited by Nicholas Ribush:

These days, even though many people realize the limitations of material comfort and are interested in following a spiritual path, few really appreciate the true value of practicing Dharma. For most, the practice of Dharma, religion, meditation, yoga, or whatever they call it, is still superficial: they simply change what they wear, what they eat, the way they walk and so forth. None of this has anything to do with the practice of Dharma.

Before you start practicing Dharma, you have to investigate deeply why you are doing it. You have to know exactly what problem you’re trying to solve. Adopting a religion or practicing meditation just because your friend is doing it is not a good enough reason.

Changing religions is not like dyeing cloth, like instantly making something white into red. Spiritual life is mental, not physical; it demands a change of mental attitude. If you approach your spiritual practice the way you do material things, you’ll never develop wisdom; it will just be an act.

Before setting out on a long journey, you have to plan your course carefully by studying a map; otherwise, you’ll get lost. Similarly, blindly following any religion is also very dangerous. In fact, mistakes on the spiritual path are much worse than those made in the material world. If you do not understand the nature of the path to liberation and practice incorrectly, you’ll not only get nowhere but will finish up going in the opposite direction.

Therefore, before you start practicing Dharma, you have to know where you are, your present situation, the characteristic nature of your body, speech and mind. Then you can see the necessity for practicing Dharma, the logical reason for doing it; you can see your goal more clearly, with your own experience. If you set out without a clear vision of what you are doing and where you’re trying to go, how can you tell if you’re on the right path? How can you tell if you’ve gone wrong? It’s a mistake to act blindly, thinking, “Well, let me do something and see what happens.” That’s a recipe for disaster.

Buddhism is less interested in what you do than why you do it—your motivation. The mental attitude behind an action is much more important than the action itself. You might appear to outside observers as humble, spiritual and sincere, but if what’s pushing you from within is an impure mind, if you’re acting out of ignorance of the nature of the path, all your so-called spiritual efforts will lead you nowhere and will be a complete waste of time.

Often your actions look religious but when you check your motivation, the mental attitude that underlies them, you find that they’re the opposite of what they appear. Without checking, you can never be sure if what you’re doing is Dharma or not.

You might go to church on Sundays or to your Dharma center every week, but are these Dharma actions or not? This is what you have to check. Look within and determine what kind of mind is motivating you to do these things.

Please continue to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive to read the rest of this chapter and the Q & A session that followed.

Excerpted from Chapter 4 of Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “Attitude is More Important than Action,” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at Theosophical Society, Adyar Theatre, Sydney, Australia, April 7, 1975, published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. You can read this book online, listen to the audiobook, access links to translations or download a PDF. LYWA Members can download the ebook for free.

You can also order a paperback copy from Amazon’s print-on-demand service. Go to the Amazon website in your region to find the best price for a print-on-demand copy.

Lama Thubten Yeshe (1935–1984), who founded the FPMT organization with Lama Zopa Rinpoche, was able to translate Tibetan Buddhist teachings into clear ideas that resonated with the Western students he met and taught in the 1970s and ’80s.

You can find additional teachings, discourses, and advice from Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website.

Foundation for the Preservation of Mahayana Tradition (FPMT), is a Tibetan Buddhist organization dedicated to the transmission of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and values worldwide through teaching, meditation and community service.

4

Lama Yeshe’s Wisdom: Experiencing Silent Wisdom

Lama Yeshe at Chenrezig Institute, Australia, 1975. Photo donated by Wendy Finster to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind is one of the most beloved free books from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. The six teachings contained in this volume come from Lama Yeshe’s 1975 visit to Australia. They are all filled with love, insight, wisdom and compassion, and accessible question-and-answer sessions.

Today we share Chapter 3 of Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, “Experiencing Silent Wisdom” from a talk given by Lama Yeshe at Prince Phillip Theatre, Melbourne University, April 6, 1975. Edited by Nicholas Ribush.

When your sense perception contacts sense objects and you experience physical pleasure, enjoy that feeling as much as you can. But if the experience of your sense perception’s contact with the sense world ties you, if the more you look at the sense world the more difficult it becomes, instead of getting anxious—“I can’t control this”—it’s better to close your senses off and silently observe the sense perception itself.

[Meditation]Similarly, if you’re bound by the problems that ideas create, instead of trying to stop those problems by grasping at some other idea, which is impossible, silently investigate how ideas cause you trouble.

[Meditation]At certain times, a silent mind is very important, but “silent” does not mean closed. The silent mind is an alert, awakened mind; a mind seeking the nature of reality. When problems in the sense world bother you, the difficulty comes from your sense perception, not from the external objects you perceive. And when concepts bother you, that also does not come from outside but from your mind’s grasping at concepts. Therefore, instead of trying to stop problems emotionally by grasping at new material objects or ideas, check up silently to see what’s happening in your mind.

No matter what sort of mental problem you experience, instead of getting nervous and fearful, sit back, relax, and be as silent as possible. In this way you will automatically be able to see reality and understand the root of the problem.

[Meditation]When we experience problems, either internal or external, our narrow, unskillful mind only makes them worse. When someone with an itchy skin condition scratches it, he feels some temporary relief and thinks his scratching has made it better. In fact, his scratching has made it worse. We’re like that; we do the same thing, every day of our lives. Instead of trying to stop problems like this, we should relax and rely on our skillful, silent mind. But silent does not mean dark, non-functioning, sluggish or sleepy.

[Meditation]So now, just close your eyes for five or ten minutes and take a close look at whatever you consider your biggest problem to be. Shut down your sense perception as much as you possible can, remain completely silent and with introspective knowledge-wisdom, thoroughly investigate your mind.

[Meditation]Where do you hold the idea of “my problem”?

[Meditation]Is it in your brain? In your mouth? Your heart? Your stomach? Where is that idea?

[Meditation]If you can’t find the thought of “problem,” don’t intellectualize; simply relax. If miserable thoughts or bad ideas arise in your mind, just watch how they come, how they go.

[Meditation]Don’t react emotionally.

[Meditation]Practicing in this way, you can see how the weak, unskillful mind cannot face problems. But your silent mind of skillful wisdom can face any problem bravely, conquer it and control all your emotional and agitated states of mind.

[Meditation]Don’t think that what I’m saying is a Buddhist idea, some Tibetan lama’s idea. It can become the actual experience of all living beings throughout the universe.

I could give you many words, many ideas in my lecture tonight, but I think it’s more important to share with you the silent experience. That’s more realistic than any number of words.

[Meditation]When you investigate your mind thoroughly, you can see clearly that both miserable and ecstatic thoughts come and go. Moreover, when you investigate penetratingly, they disappear altogether. When you are preoccupied with an experience, you think, “I’ll never forget this experience,” but when you check up skillfully, it automatically disappears. That is the silent wisdom experience. It’s very simple, but don’t just believe me—experience it for yourself.

[Meditation]In my experience, a silent lecture is worth more than one with many words and no experience. In the silent mind, you find peace, joy and satisfaction.

[Meditation]Silent inner joy is much more lasting than the enjoyment of eating chocolate and cake. That enjoyment is also just a conception.

[Meditation]When you close off your superficial sense perception and investigate your inner nature, you begin to awaken. Why? Because superficial sense perception prevents you from seeing the reality of how discursive thought comes and goes. When you shut down your senses, your mind becomes more conscious and functions better. When your superficial senses are busy, your mind is kind of dark; it’s totally preoccupied by the way your senses are interpreting things. Thus, you can’t see reality. Therefore, when you are tied by ideas and the sense world, instead of stressing out, stop your sense perception and silently watch your mind. Try to be totally awake instead of obsessed with just one atom. Feel totality instead of particulars.

[Meditation]You can’t determine for yourself the way things should be. Things change by their very nature. How can you tie down any idea? You can see that you can’t.

[Meditation]When you investigate the way you think—“Why do I say this is good? Why do I say this is bad?”—you start to get real answers as to how your mind really works. You can see how most of your ideas are silly but how your mind makes them important. If you check up properly you can see that these ideas are really nothing. By checking like this, you end up with nothingness in your mind. Let your mind dwell in that state of nothingness. It is so peaceful; so joyful. If you can sit every morning with a silent mind for just ten or twenty minutes, you will enjoy it very much. You’ll be able to observe the moment-to-moment movement of your emotions without getting sad.

[Meditation]You will also see the outside world and other people differently; you will never see them as hindrances to your life and they will never make you feel insecure.

[Meditation]Therefore, beauty comes from the mind.