- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

20

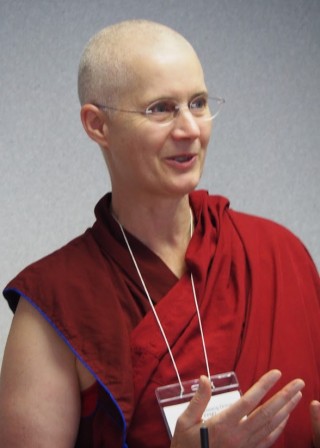

Gethsemani Abbey, New Haven, Kentucky, May 2015. Photo by Martin Verhoven.

In May 2015, Ven. Losang Drimay, teacher and resident at Land of Medicine Buddha in Soquel, California, was one of 12 Buddhists to meet with 17 Catholics at Gethsemani Encounter IV. The first Encounter took place nearly 20 years earlier at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, the home and retreat of the late Trappist monk, writer and mystic Thomas Merton (1915-1968) in New Haven, Kentucky, in the Unites States. His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who was a friend of Merton, attended the first Encounter. Each Encounter allows a small group of spiritual practitioners to live, practice, talk and rejoice together in a monastic setting.

Both His Holiness and Lama Zopa Rinpoche encourage interfaith dialogue, which can take many forms. Angelica Walker spoke with Ven. Drimay about her experiences at the interfaith gathering and what she took from it.

How did you become involved in the conference?

I heard about the conference through my friend, Reverend Heng Sure. He is the resident monk at Berkeley Buddhist Monastery in Berkeley, California, which is a branch of City of Ten Thousand Buddhas.

Rev. Heng Sure speaking at the Gethsemani Encounter IV, Kentucky, US, May 2015. Photo by Martin Verhoven.

What traditions were represented at the conference?

It was just Catholics and Buddhists, and not all Catholic traditions, but specifically Benedictines, monastics who follow the Rule of St. Benedict. There’s an agency called Monastic Interreligious Dialogue which one of the organizers, Sister Hélène, called a “pontifical commission,” meaning someone from the Vatican says it’s OK to do this. Essentially, the conference has the official seal of approval from the Pope.

What traditions of Buddhism were represented?

The majority were Zen practitioners, but when I use the word “Zen,” I’m using that term very loosely. I should probably say “Chan” because it wasn’t necessarily people from the Japanese Zen tradition. There was only one monk from the Japanese Zen tradition from Shasta Abbey. The others were following the Chan tradition from China. At times I had to pipe up and say, “Not all Buddhists say what Zen Buddhists say!” There were only three Tibetan Buddhists there, so we were slightly outnumbered. Besides myself, there were two nuns from Sravasti Abbey in Washington State, which is the abbey that Ven. Thubten Chodron founded near Spokane. Interestingly, those two nuns had been raised Catholic, so they were perhaps more familiar and conversant with Catholic ideas and rituals than I was. I was raised in a Methodist Sunday school and knew about Catholicism only through my friends who went to Catholic church.

One of the nuns from Sravasti Abbey had a very interesting connection with the Abbey of Gethsemani: one of her distant grandfathers sold the land to the Gethsemani monks! Her ancestors are buried in the churchyard at the front entrance. She remembers going there with her parents 30 years ago to visit the family graves.

Why do you think it’s important for this type of interfaith conference to take place?

I think it helps both parties freshen up their own practice and way of doing things. After you’ve been in a certain place for a while, things can either get stale, or you just forget there could be a different way to be doing things or thinking about things. It’s not that either side will stop being Catholic or stop being Buddhist, but you may get a new angle on what you’re already doing. For example, by hearing the presentation on lectio divina (“divine reading,” the practice of prayerful and contemplative scripture reading), I will continue thinking about how this applies to my own reading practices.

In fact, I was reminded of what Ven. René Feusi mentions in The Beautiful Way of Life: A Meditation on Shantideva’s Bodhisattva Path, the book that’s recently been published, which basically came out of a retreat practice of what could be called divine reading. He doesn’t call it that, but he would read a verse, think about it, make it his own – you roll it around in your own psyche and see if it speaks to you. What does it say to you, how would you put it in your own words? It was important to hear that there’s another tradition where that’s not accidental, but rather that this is the way to work with scripture.

The Catholics in this particular group were very liberal. The fact that they’re having conversations with Buddhists is a sign that they are liberal. The Gethsemani group has been very interested in learning meditation, and one of the monk-priests who participated took himself over to Japan years ago and learned zazen. Zazen is now a part of his daily practice, not that he’s Buddhist – he’s not giving up his Catholic world-view. But every day he practices on a cushion the way he learned from a Zen master.

They had a retreat at the Abbey of Gethsemani with His Holiness the Dalai Lama during which he taught the Catholic participants meditation. It was only offered to Catholics; it wasn’t open to the general public. They’ve been interested in learning Buddhist methods in order to keep their practice fresh and alive and moving forward.

The other thing that was fascinating to me was that one of the presentations was about the nuns, and specifically how someone becomes what Buddhists refer to as “ordained,” which they call “profession.” What we might call “novice ordination,” they call the “rite of first profession.” Later they go through the “rite of perpetual profession.” So it’s like what we Buddhists call “novice ordination” and “full ordination.” We saw a YouTube video of a woman taking her perpetual profession, held at a monastery in Minnesota, which I thought was interesting.

Informal discussion at breakfast during the interfaith gathering, Gethsemani Abbey, May 2015. Photo by Martin Verhoven.

What did you enjoy most about the event?

It would definitely be the personal connections that usually happened outside of the formal presentations, like when you’re sitting around the dining table talking during the breaks.

But there are two other things that I was pleasantly surprised about. I was expecting the presentations to be boring – usually these types of things are something I feel like I have to just tolerate. But they weren’t boring, and I think the reason was that they were coming from a place of personal experience. The Catholics who were presenting were so scholarly and well-prepared. They had their papers typed up and documented. The Buddhists tended to just speak more off the top of their heads, but the Catholics were very well-prepared. It wasn’t dry scholarship; it was very informative and I learned new things about how they do things and why.

My other favorite part of the event was choir, which is a huge part of what happens at the abbey – about seven or eight times a day. During these choir periods, the monks who live at the abbey gather in the church to do Gregorian chants. The church is very plain. They’ve stripped away all the decorations because they’re Trappist, a Catholic cloistered contemplative order known for discipline and simple living. Usually, the public is behind a screen, but they actually had us – the Buddhist participants – in the choir stalls with them. So, not only were they allowing women in the choir stalls, they were allowing heathens in the choir stalls, if you can call us that. It was very liberal of them, I thought. They had us interspersed with the monks so that they could help us turn the pages because it’s very complicated. Each session, there’s a different “recipe” of what you’re going to recite. They’re working their way through the Psalms, so you have to know which Psalm they’re on each day. There are three different prayer books and bookmarks in different places, so even though it was all spelled out for us, we still needed someone showing us which page we were on. They were very generous and patient with us. I thought about how some of the monks were OK with having us there, and some were probably not that into it, so I was especially conscious of that. It wasn’t everybody’s decision to have the Buddhists in the choir stalls.

They have a sign posted in the dining room that says something like: “Dear retreatants, please don’t sing louder than the monks and try to keep up the pace.” I thought, “I would never dare to sing louder than the monks!” I was just mouthing the words.

Did you lead any sessions at the conference?

Because I was a late addition to the program, I just added to what Rev. Heng Sure was already scheduled to present. He had a session on maitri (Pali: metta), loving-kindness meditation, and fortunately I’m very used to having to suddenly stand up and speak into the microphone, so I got up and said something about that. I wasn’t leading them in a meditation, I was talking about one of the ways to develop bodhichitta and the particular type of love that is mentioned for that topic. The article on what I talked about – “Love Based on Like” – is on the Dialogue Interreligieux Monastique/Monastic Interreligious Dialogue website.

Some of the presentations were more conceptual and some of the presentations were specifically practice, which they call praxis, or, roughly, an accepted practice or custom within their order. Rev. Heng Sure was scheduled to give a praxis presentation on bowing, or prostration. He is particularly qualified to give that presentation because back in the 1970s he was famous for prostrating up Highway 1, from south Pasadena in California up towards Ukiah – more than 800 miles (1,287 km). It took place over two years. The book that is based on that pilgrimage is called Three Steps, One Bow. He has a slideshow from that pilgrimage, which he presented.

When he was done presenting, he said, “Drimay, do you have anything to add?” So I got up and showed them how to do the full-length bow according to the Tibetan tradition, and I mentioned how in the Tibetan tradition the 100,000 prostration practice is one of the standard preliminaries. I also shared that prostrating is a normal practice, that Tibetan people love to prostrate across the country, and sometimes they prostrate right out of the country!

What were some of the ritualistic similarities and differences between the Buddhists and the Catholics?

One presenter was a Korean Catholic monk-priest. In the Catholic tradition, monks can be priests and priests can be monks, but they’re not the same thing. At Gethsemani, out of 42 monks, seven are priests. They’re all monks, but only some of them are priests as well. This Korean monk-priest presenter, Father Anselmo, spoke about being from a country which is traditionally Buddhist. He talked about the Zen imagery of The Ten Ox Herding Pictures, which is similar to the Tibetan Buddhist Elephant on the Path. Father Anselmo presented the Zen ox herding diagrams and related them to the Christian path. That was the presentation that was the most cross-cultural. Most other people were just presenting their tradition’s practices or ways of thinking, but he was bridging traditions right from the start.

One of the Christian presentations I found most interesting was presented by Brother Lawrence, who was the resident participant from the Abbey of Gethsemani. He explained what they’re doing during their “liturgy of the hours,” also called the “offices.” What they’re doing is reciting the Psalms, which are part of the Old Testament. Brother Lawrence describes this literature as expressing every kind of human experience. The thing that each Psalm has in common is that they’re all directed to God. The Psalms include some very violent, lustful aspects; some of it is joyful; some of it is sad or angry. To an outsider, it seems very surprising and strange that these Catholic monks are spending their careers, from before the sun comes up to when the sun goes down, reciting Old Testament literature. They’re basically reciting Jewish scriptures. He asked, “So why do we do this?” He answered his own question, saying, “Because that’s how it has always been done since the time of the Desert Fathers.” This means they are carrying on a tradition which pre-dates Jesus. They’re carrying on a tradition which is more than just Christian. I find that fascinating! It’s like they’re human time capsules.

The monks recite different Psalms each session and work their way through them. The chapel has two banks of choir stalls, so side A will recite the first two lines, side B will recite the next two lines, and they call and respond like that across the aisle. Then they recite something called the “doxology,” which is remembering the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit. They have some other songs as well; every night they sing a song to Mother Mary.

When somebody from the monastery dies, they wrap up the body in a shroud and place the shroud between the two banks of choir stalls, and they recite, taking turns keeping vigil around the clock, until they’ve recited all 150 of the Psalms. That’s their funeral rite.

Their rituals seemed very transhistoric – timeless. These men spend their lives doing this. They have other jobs and hobbies and do things in their free time, but no matter what else they have going on, they still have to show up seven or eight times a day in the church.

Did you get to know many of the resident monks at the abbey?

We didn’t talk to all of them. Only one of the monks who lived at the abbey was a full-time participant in our conference. The other participants weren’t from Gethsemani. They were from monasteries in Minnesota, Kansas, and Pennsylvania, among other places. Some of the Gethsemani monks dropped in on the conference and I got to know some of the others just by meeting them while they were doing their daily jobs – working the front desk or giving us rides back and forth. After the conference was over, there was a weekly Thomas Merton study group which was led by one of the resident monks. I sat in on it and got to know some of the others through meetings like that.

How do the monks support themselves?

They support themselves entirely by making fruitcake and fudge. They lace both liberally with bourbon. They did have one or two versions that didn’t have the bourbon in it. At first, they had laid some out on a table for us and then quickly realized they had to label it “non-alcohol”!

What were your living quarters like?

They have a beautiful guest house. It’s attached to the main cloister, but outside of it. The set-up of the building was comprised of very traditional architecture where the monks live around a courtyard and at one edge of the courtyard is the church. The monks have their own entrance into the church. On the other side of the courtyard, at the front edge of the church, is a wing which is three-stories high or more of guest facilities, with a dining room and a few meeting rooms. The rooms were very nicely appointed. Each room was single, with a bed, a desk, a reading chair, and a bathroom – much like my own set-up here at Land of Medicine Buddha. So, there was no hardship! It was all very simple, but it had everything I needed.

Visit to Thomas Merton’s retreat cabin, Gethsemani Abbey, Kentucky, US, May 2015. Photo by Martin Verhoven.

How did the conference come to a close?

Our closing ceremony was held at Thomas Merton’s retreat cabin, which was a little walk down a country road to get to. The Catholics, and even some of the Buddhists who have been influenced by Thomas Merton, felt very moved to be able to visit his cabin; it was like going to Milarepa’s cave or something like that. Some of the Catholic visitors were moved to tears when they went into his cabin. It’s still a working retreat house. Each monk at Gethsemani gets one week a year of personal retreat at the cabin.

After visiting the cabin, we gathered on the front porch and said one thing that was meaningful to us about the gathering and sang some songs. There were several monks who were musical, Rev. Heng Sure among them. One of them played the Native American flute, and I thought, “It’s not just the Buddhists who like to play music!”

Father Michael plays a Native American flute at the close of the Gethsemani Encounter IV, May 2015. Photo by Martin Verhoven.

Ven. Losang Drimay has been studying, practicing and working in FPMT centers since 1984, receiving hundreds of hours of instruction from the many qualified lamas and senior teachers. She eventually took ordination in 1991. She has worked for the FPMT International Office, served as resident teacher at Ocean of Compassion Buddhist Center in Campbell, California for 11 years, and currently lives and works at Land of Medicine Buddha leading regular meditations and classes.

Angelica Walker grew up at Vajrapani Institute in Boulder Creek, California. She met Ven. Losang Drimay when she was three years old. She will soon graduate from the University of California, Santa Cruz with a degree in Literature and Creative Writing.

- Tagged: in-depth stories, interfaith, interview, online feature, ven. losang drimay

- 1

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.There is no samsaric pleasure that is new, so let go of the clinging that creates samsara.