- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

15

Freda Bedi’s ‘Big’ Life: An Interview with Vicki Mackenzie

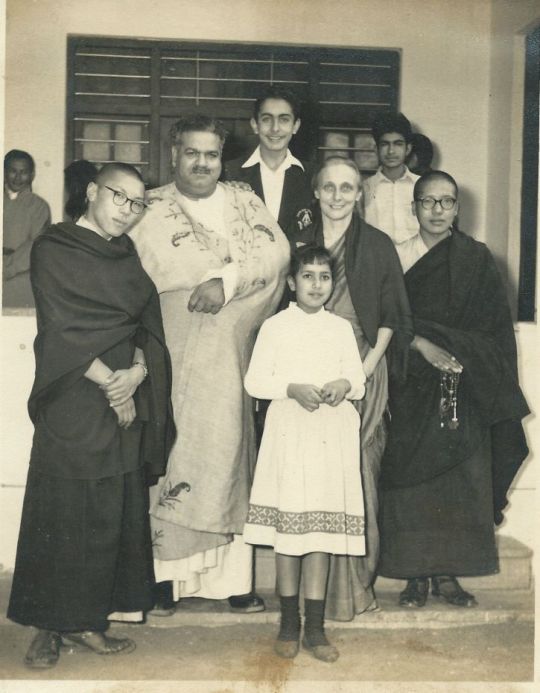

1963. The Young Lamas Home School, Dalhousie, India. Freda Bedi with the reincarnated Tibetan lamas she was educating in English and modern history to bring Buddhism to the outside world. (Photo courtesy of Faith Grahame via Shambhala Publications, Inc.)

Freda Bedi, born in 1911 in England, lived a “big” life. She attended Oxford University, where she met and married Baba Pyare Lal Bedi, who was the sixteenth direct descendant of Guru Nanak, founder of the Sikh religion. They moved to India in 1934 and were active in the Indian national independence movement; she was one of Gandhi’s handpicked satyagrahis. Bedi later played a significant role in providing support to some of the first Tibetan Buddhist lamas to teach Westerners, primarily through the Young Lamas Home School, which she established in 1960. Lama Zopa Rinpoche was one of the many young tulkus who attended the school. He often speaks of how Freda Bedi helped him.

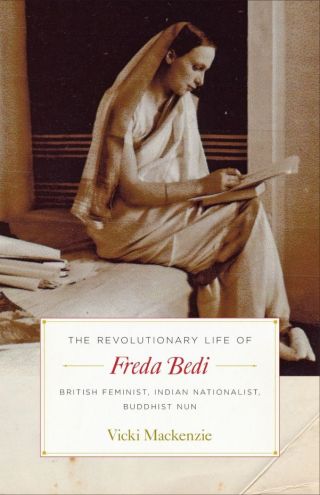

In April 2017, British journalist Vicki Mackenzie talked with Mandala about her new book The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi: British Feminist, Indian Nationalist, Buddhist Nun. Mackenzie discussed with Mandala managing editor Laura Miller the origins of the book, Freda Bedi’s many achievements, and how she managed to accomplish several lifetimes of work helping others in just one life.

Freda Bedi, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, and Lama Yeshe with Marcel Bertels and Nick Ribush in foreground, Kopan Monastery, Nepal, March 1976. Photo courtesy Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. About the visit from Big Love: “Rinpoche told his old teacher, Freda Bedi, now Sister Karma Tsultrim Khechog Palmo, that he just wanted to meditate. Sister Palmo had accompanied His Holiness the sixteenth Karmapa to Boudhanath for the opening of a big new Nyingma-Kagyu monastery, where he gave three months of extensive teachings and initiations. Lama Yeshe invited her to visit Kopan where she advised Western practitioners to pray to the guru until tears fell from their eyes.”

Mandala: What inspired you to write this book?

Vicki Mackenzie: I never met Freda Bedi. It was such a shame. But from my earliest days in the Dharma, I heard about her. I went to Kopan in November 1976 for my first course there, and she had just visited. There was a buzz because Lama Yeshe had brought her into the gompa, into “the Tent” as it was then called, and put her on the throne. He made three full-length prostrations to her. Unfortunately, she died shortly afterwards, in 1977.

Then when I was writing the book Cave in the Snow, I heard about her from Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, who had helped her at her Young Lamas Home School. Tenzin Palmo said she was such an extraordinary woman, a powerhouse. She had an incredible life, a big life, many lives in one lifetime. So my ears pricked up. And after Cave in the Snow, Tenzin Palmo kept saying, you really must write a book about Freda Bedi, women need inspirational role models. But I wasn’t interested then because I didn’t want to write a book on another British woman who had become a Tibetan nun! She kept pushing though. And then I got a letter from Ranga Bedi, Freda Bedi’s eldest son, saying we’re looking for someone to write a book about our mother. He said the Dalai Lama thought a book should be written. His Holiness didn’t specify me, but I thought, “Well, if His Holiness thinks a book should be written … I’ll take it on.” So the momentum gathered until I gave in.

Mandala: How did you get the information you needed?

Mackenzie: The Bedi family wanted the book written, so they handed over their mother’s recordings, letters, writings: it was the next best thing to being able to actually talk to her. She came alive in these materials. But not completely. It would have been so great to interview her. You get the best material when you can sit someone down and ask them the questions that need to be answered and not just take the stuff they want to give you. That way you can also assess the person’s character and “feel.” That made it a difficult book to write. The Bedi children, who are grown-ups now, all gave me interviews. But then I needed to flesh it out. So I did a lot of traveling, finding people who knew her, seeing the places she had loved and where she had worked. It was a lot of talking!

Mandala: What about Lama Zopa Rinpoche? He attended the Young Lamas Home School.

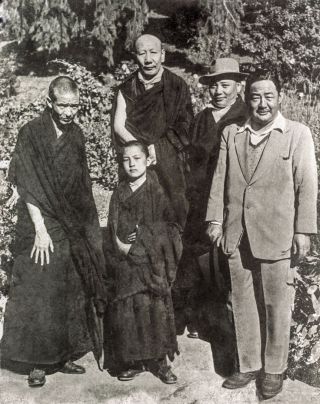

A young Lama Zopa Rinpoche with the 6th Yongzin Ling Rinpoche (1903 – 1983), senior tutor of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Mackenzie: Rinpoche was one of her pupils, who she plucked out of the Buxa Duar refugee camp when he was young and very sick. Rinpoche is always talking about her, so I drew on what I had heard from him. I sometimes wonder if Lama Yeshe wasn’t bowing to her at Kopan partly because she had looked after his heart disciple.

One very important interviewee was Akong Rinpoche, who talked to me at Samye Ling, Scotland, just before he was tragically killed. Freda had “adopted” him in 1960 along with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. I interviewed people who had worked with her at the Young Lamas Home School, which she established in 1960. I talked to the volunteers who knew her at the school, and Indians who knew her socially, friends of her family. I interviewed Gelek Rinpoche, who had lived with her in Delhi as one of her pupils. With great difficulty, I tracked down her devoted nun assistant—a very feisty character. I found the nunnery that Freda established in India and talked to the nuns who had known her. They were utterly devoted to her, and kept her room locked up as a shrine. I interviewed Tibetan officials who knew her when the Tibetans came into exile, her niece in England, Pema Chödrön, Joanna Macy, and Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, who very kindly wrote the foreword to the book. It was like trying to piece together a giant jigsaw puzzle. It took me six or seven years. It was very, very difficult to get a comprehensive picture of this extraordinary woman because she was involved in so many activities.

Mandala: You mentioned that she lived many lives. Tell me more about that.

Mackenzie: Freda won three scholarships to Oxford. She was mega-bright. Curiously, she was determined without actually being ambitious. She didn’t necessarily want to go to Oxford. A school friend’s family asked Freda to study with their daughter to encourage her as she wasn’t very bright. At the last minute, Freda decided to take the examination too. Ironically, Freda got a scholarship and her friend didn’t.

The young, in-love Freda at Oxford, England, 1932. Taken by her fiancé, Baba Pyare Lal Bedi. Photo courtesy of Bedi family archives via Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Oxford opened up a whole new world for the provincial Freda. There she met a charismatic Sikh called Baba Pyare Lal Bedi who was the sixteenth direct descendant of the founder of the Sikhs. He got her into Marxism and the Indian independence movement. She met Gandhi, who lectured there, and was deeply impressed. She married Bedi, who warned her that she would spend a lot of her married life waiting outside prison walls, which turned out to be true. So returned with him to India and joined Gandhi’s peaceful resistance movement against the British. At the same time she was a professor, journalist, and mother. Freda helped to rouse the Indian people with her amazing oratory; she was extremely articulate in Gandhi’s cause. Gandhi chose her personally to be what is known as satyagrahi, one of those willing to go to prison and even die for the cause. Of course she was duly arrested, and became the first British woman to be imprisoned for insurrection. After that, she became a heroine in India.

But right from childhood she was a spiritual seeker. She would go to church to try and meditate before school. And she read everything she could on the East. While she was at university and then in India, she explored every kind of spirituality she could, very diligently. She read all of the Koran, the Torah, explored Sikhism and Hinduism. And she continued to meditate and do yoga and had some profound spiritual experiences. But there was no Buddhism in India at that time.

She also had a strong social conscience and innate compassion. She was desperately keen to help anybody in need and she hated, hated inequality and suffering of any kind. So after India achieved independence in 1947, she threw herself into working for the refugees who arrived due to the partition of India and Pakistan. There was a bloodbath at the time of partition, if you recall, with traumatized refugees on both sides of the border. So she became a social worker, always working for the poor, especially the rural poor. At the same time she mixed with the great and the good. She knew Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi. She knew Lady Edwina Mountbatten, who was the wife of the last British viceroy of India. The Bedis knew all the leading writers, artists, and politicians and were a celebrated couple at society’s top cocktail parties.

Nehru sent Freda to Burma in 1952 on a UNESCO mission. While she was there, she encountered Buddhism for the first time and learned vipassana meditation from Mahasi Sayadaw and Sayadaw U Titthila. She had a kind of awakening experience. She was never the same after that.

And then Nehru sent her, in 1959, to look after the Tibetan refugees in India when His Holiness came into exile. She saw all these refugees, and was working day and night, day and night, to help them, and she saw in them all a spiritual quality she had never seen before. And that was it. It was the tulkus who impressed her the most. She recognized that it was the tulkus who would bring Buddhism to the West. At the time, nobody else was thinking along those lines. Only Freda saw it. Everything was in such disarray. She met Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Akong Rinpoche, and felt a deep affinity with the two of them. She took them into her house in Delhi to live with her family.

1960. Freda Bedi with family members: her husband Baba Pyare Lal Bedi, her son Kabir, and her daughter Guli on the steps of their small Delhi flat with newly “adopted” family members, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Akong Rinpoche, found by Freda in the refugee camps. They lived together for several years. Photo courtesy of Bedi family archives via Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Following her hunch, Freda set up a school for the young rinpoches. It started in Delhi with Nehru’s permission and help. And His Holiness supported it. He thought that the most important thing for the young rinpoches was an education. Later she moved the school to Dalhousie and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, who had tuberculosis at that time, went there. He was so keen to learn English. And Freda Bedi found him sponsors, and got him robes and medicine.

Mandala: Tell me a little bit more about the school.

Mackenzie: It was nonsectarian. Freda was never interested in divisions so it was open to all the schools of Buddhism. She taught the tulkus herself, and she commandeered passing Westerners as well to teach English and Western topics. Tibet had been completely isolated, and the young Tibetans didn’t know anything about the outside world. She knew that she had to give them a more comprehensive education. But they also did their prayers and practices according to their own traditions. She was constantly fundraising and getting sponsors for them. She never ever had any money and was totally non-materialistic herself, but she was a very powerful woman, with a great intellect and tremendous connections with the most powerful people in India.

Mandala: And she did some work for nuns as well?

Mackenzie: She established the first nunnery in exile. She really, really believed in the equality of women. In fact, in the exile community, the nuns got their first nunnery, Karma Drubgyu Thargay Ling, before the monks got their first monastery. And it’s still going. On a personal note the sixteenth Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje encouraged her to become the first fully-ordained Tibetan Buddhist nun of any nationality. It was yet another historical milestone she clocked up. She was the first gelongma, which helped pave the way. Tenzin Palmo followed and so did all the others. It’s amazing, isn’t it?

Mandala: I understand she did some translation.

Mackenzie: She was an ace at languages. She just had a knack. She had studied French; that’s what got her into Oxford. She learned Hindi and Tibetan, and she was translating texts very early on. That was one of her first jobs, which she was doing on the side. She was one of the first translators of Tibetan texts.

Kagyu nuns, India. Photo by Olivier Adam.

Mandala: Her commitment to helping others meant her family missed her at times.

Mackenzie: Missed her because she was away a lot and when she was at home they had to share her. You know, she was called “Mummy-la” by the Tibetans. They all called her Mummy-la and she sort of saw herself as a universal mother. And the Tibetans, most of them, regarded her as an emanation of Tara. But her own children, I think, often took second place. So I explore that in my book as well: the discrepancy between universal mother and actual mother at home cooking meals and generally putting her children before anything and anyone else. Freda never did that! I think it’s often an issue women face. Our myth of motherhood is very strong. Freda undoubtedly loved her children and they loved her, but she also had her eye on the bigger picture.

Mandala: Her work has had long-term impacts, hasn’t it?

Mackenzie: She got Trungpa Rinpoche a scholarship to Oxford. And he went on from there to America where his impact was enormous. He and Akong Rinpoche established the first Tibetan monastery in the West, in Scotland, Samye Ling. I don’t think you can overestimate the influence of these two lamas. And Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s global influence is inestimable. Freda mentored many other tulkus like Thartang Tulku and Gelek Rinpoche, all of whom have contributed a colossal amount. Freda’s role was pivotal.

And she persuaded the sixteenth Karmapa to go on his first tours to Europe and America. She did that personally, because she was his close disciple, living in a room just beneath his in Rumtek, and he listened to her. She said to him, “The West definitely is ready, go, please, please, they are ready, give them the Dharma.” She arranged for him to meet the Pope. She went with him, organizing all the way and acting as his intermediary.

Mandala: Was she a serious practitioner?

Mackenzie: Yes, which surprised me. I don’t know when she found the time to practice. I discovered that, while she was on these tours to South Africa and America, she was conducting high initiations with the permission of the Karmapa. So she must have been an extraordinary practitioner. And the Karmapa told her assistant, the nun who was with her all the time, that she was an emanation of Tara. She was doing these extraordinary empowerments. Her explanations were exceptionally profound and very clear. In the book, I have tried to put in, especially for Buddhist readers, excerpts of talks she gave while she was doing the overseas tours, both on the radio and live. It seems that she had a high understanding of the Dharma.

And her devotion to the sixteenth Karmapa was absolute. She didn’t have to learn guru devotion. Her first meeting with him was remarkable. While she was working with the Tibetan refugees, they told her she must go and meet the Karmapa, who had just arrived. It was a long journey on horseback, and she didn’t really know who he was. But she trekked up to see if she could help him. And he revealed himself to her as the Buddha. He was instantly her heart guru. Her devotion to him was so absolute that it annoyed her daughter, who was brought up by her mother to be an independent woman. “Whatever are you doing obeying everything he says? I thought you were an intelligent, liberated woman!” That was her daughter’s view.

Mandala: As a woman, she was quite radical, wasn’t she? For example, she was the primary income earner in her family.

Mackenzie: Yes, her husband had a devil-may-care attitude that life would take of itself. And he was in prison too, for years, because of the struggle for Indian independence. So she was the main breadwinner. She didn’t seem to mind. She worked so hard. All the time, work, work, work. And I think she and her husband believed in freedom of choice for both of them actually. It was radical, yes. The Bedis were a remarkable family. Very advanced, very enlightened. They welcomed Freda into their midst, for example, and treated her like a daughter, even though she was British. They were very special people, her in-laws. She loved them, and they loved her. Her husband’s mother lived with them when she was old and they looked after her. Really, they were all characters.

That’s something I tried to explore in the book. I didn’t want to do a hagiography. I wanted to show the reality. And Freda was big character, and complex. And in a way she was “called.” Her life had, like Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo’s, a trajectory, even though Freda didn’t meet her guru, her path, until she was middle-aged, by which time she had had an extraordinary life already. She had tasted everything. Career, being a wife, a mother, a socialite, cocktail parties, political activism, jail. But all the time she was always on this trajectory to bring about a better world, to eliminate suffering.

She is an icon in the transmission of Buddhism to the West, an icon. And yet, she has remained fairly unknown. Why has her song never been sung? His Holiness was right. Her story deserves to be told. There was even a hint in her letters that it was through her contacts with Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi that Nehru was persuaded to take His Holiness in, to let him settle in India. That’s in the book. It’s just hinted at, but she could have been an important influence in that momentous decision. Maybe Lama Yeshe was aware of this other role she may have played too.

Then she kept working and working even though her health was never good. On her last tour you can hear on the recordings of her teachings that she can hardly breathe. She was exhausted, physically wrung out—you can hear it. But she kept on going. Apart from teaching and touring, she was still running organizations and getting sponsors for Tibetan causes, refugee camps, and families: she kept that going by endless letter writing. How she did it all, I just do not know. She crammed a lot in!

Mandala: How did writing the book impact you?

Mackenzie: It’s exhausted me. [Laughs] It has been a long haul, weaving all these strands together and hopefully making her come alive to the reader. I also feel tremendously honored to have spent time with her in this way. She did so very much for India, for Tibetans, for the Dharma, for women. She amazes and inspires me. I feel such gratitude for all she did.

She has been a student of Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche since 1976.

Mandala is offered as a benefit to supporters of the Friends of FPMT program, which provides funding for the educational, charitable and online work of FPMT.

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.The workshop is in the mind.