- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

10

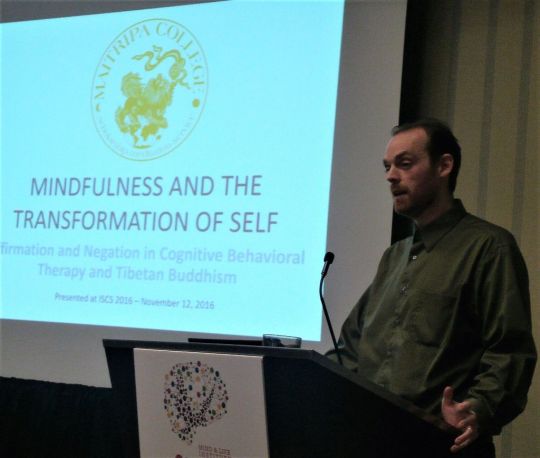

Photo courtesy of Jacob Sky Lindsley.

Jacob Sky Lindsley is a graduate of two Buddhist schools in the US, having received a bachelor degree from the University of the West near Los Angeles, California, and a master of arts degree from FPMT-affiliated Maitripa College in Portland, Oregon. He has worked for FPMT’s Vajrapani Institute as well as Maitripa College, and commences Ph.D. studies in psychology in 2017. His master’s thesis, Mindfulness and the Transformation of the Self, examines the relationship between mindfulness therapies and the Madhyamaka philosophy of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Jacob presented a paper based on this at the November 2016 International Symposium of Contemplative Studies of the Mind and Life Institute.

Jacob spoke with Mandala associate editor Donna Lynn Brown.

Mandala: What led you to look at how Madhyamaka (Middle Way) philosophy1 intersects with mindfulness?

Lindsley: I’ve spent a lot of time mulling over the Madhyamaka view of self as empty of inherent existence, and working with its meditations that help show that the true self that we think exists really can’t be found. This has convinced me that, as Buddhism maintains, our wrong view of self creates suffering. But I also have a background in psychology, so I wanted to see how mindfulness—so important in psychology now—gets at that root cause of suffering. What I found was that mindfulness-based therapies do not deconstruct the sense of self in the same way as, say, Gelugpa-style meditations. So I wanted to explore how mindfulness therapies understand the self they posit, and transform our relationship with it, compared to how the Gelug teachings do that.

I’m not trying to show that mindfulness helps people or doesn’t; other researchers have shown that it often does, and are now drilling down to understand who it helps and in what circumstances. Where there is not much clarity at this point is about how and why it helps. There are several theories, and researchers are working on it. What I’m doing is looking at how mindfulness transforms people’s relationship with the self, because that helps explain what is going on when they practice mindfulness. I think it can also illuminate how mindfulness helps—and also maybe why that help could be limited in impact.

Some of the questions I’m asking are: can mindfulness, as it is practiced therapeutically, cut the root of suffering as understood in Buddhism? If not, does it at least take a step in that direction? Or does it perpetuate or even strengthen our innate distorted view of the self? If that’s what’s going on, can mindfulness-based therapies be reworked to draw on the Madhyamaka view in order to better address suffering?

As far as I know, no one else is looking at mindfulness from a Madhyamaka perspective. I’d like to get that conversation going.

Jacob Sky Lindsley presenting his research at the November 2016 conference of the Mind and Life Institute, San Diego, California, USA. Photo by Doug Huppe.

Mandala: We hear the word “mindfulness” used in various ways. Can you clarify just what it means?

Lindsley: According to Buddhist theory, mindfulness is the mental factor that remembers to stay cognizant of the intended object of any particular moment of cognition. So if the breath is the object, mindfulness would remember to keep the breath in mind while another factor like attention would hold awareness on the breath. But nowadays we hear the word used in several ways. For example, it can refer to a kind of meditation, or to a way of being in ordinary life. Jon Kabat-Zinn says mindfulness is “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally,” which can refer to both meditation and to being mindful as we go about our day. And then psychology uses the word for certain clinical interventions: mindfulness-based therapies. With respect to meditation, there are various kinds: mindfulness of breathing, of the body, of walking, and so on; of close attention to one factor or broader choiceless awareness. So mindfulness is an umbrella term for lots of things.

Mandala: Before we talk more about psychology, can you sum up the Buddhist approach to self?

Lama Tsongkhapa. Photo courtesy of FPMT Charitable Projects.

Lindsley: All schools of Buddhism believe that a transformed experience of the self is what leads to liberation and enlightenment—the end of suffering. Shantideva, for example, makes clear that all the techniques the Buddha taught were meant to lead to a direct insight into no-self, meaning realizing that the self we think we have just isn’t there. And Buddhism says that all of our negative emotions and psychological issues are mediated by our relationship to this false idea. So getting at the sense of self and transforming it is fundamental to how Buddhism deals with suffering, whether we uproot suffering entirely by realizing that this type of self doesn’t exist and removing that appearance from our minds, or, in a shorter-term sense, reducing our suffering by easing our grasping at this wrong idea of self.

Mandala: Is it a problem if mindfulness works with the self in a different way than Madhyamaka?

Lindsley: Not necessarily, if people find mindfulness helps them that may be good enough. It might even be great. But there are two potential issues. One is that mindfulness-based approaches to reducing suffering may obscure a powerful key to healing and well-being that is central to Buddhism because it’s been proven to work—by that I mean insight into the true nature of the self. People may forget that Buddhism has perhaps more powerful methods to eliminate suffering if they think mindfulness is all that Buddhism has to offer from a therapeutic point of view. Second, the way mindfulness therapies operate may actually reinforce an innate belief in the truly-existing self. If so, that might make for short-term gain in exchange for long-term vulnerability. That’s because trading one kind of self-experience for another can help us feel better, but if Buddhist philosophy is true, undermining this innate belief is the only way to remove the potential to suffer in general. This is a pretty radical idea!

Mandala: What are the similarities in the understanding of suffering between Buddhist philosophy and mindfulness-based therapies?

Lindsley: Like Buddhism, often these therapies are based on the idea of distortion: depression, for example, and other difficulties are influenced by seeing reality in a biased way. Some people organize their experience mentally in ways that are just not accurate. Maybe they are convinced they are inherently stupid or worthless, or they can never succeed at anything, or their life will never be OK—those kinds of things. Most of us do this a little. But people who struggle with mental or emotional problems often have negative cognitive patterns or self-understandings that significantly impair their ability to function, or just make them really unhappy. These are almost always evaluations of a self. And one purpose of mindfulness is to transform that distorted sense of self to make it more realistic. The reduction in distortion then reduces suffering, generally speaking.

Buddhist philosophy also emphasizes distortion. Buddhist teachers will say that the core lesson of Buddhism is to see without distortion: just seeing reality as it is will be enough, without changing anything else, to end suffering. For example, we believe that things that are impermanent are permanent and get upset when we are proven wrong. We grab at things we are sure will make us happy and are shocked when we get hurt. This is samsara, and it’s based on distortion. The most deep-rooted distortion is our experience of self. Many Buddhist practices ease our grasping at this mistaken sense of self and that reduces our suffering.

So that sounds similar, doesn’t it? But we have to be careful because the definitions of self are different, and so are the ways that their practices transform the sense of self.

Jacob Sky Lindsley co-teaching a meditation class to the public at Maitripa College with fellow Maitripa graduate Anita Bermont, Portland, Oregon, US, March 2016. Photo by Marc Sakamoto.

Mandala: How do the ideas of self in mindfulness-based therapies differ from Buddhist ideas?

Lindsley: Even though mindfulness has roots in Buddhism, the therapies based on it use Western notions of self. The main mindfulness-based therapies more or less rely on three types of self-experience.

First, they talk about a “narrative” sense of self. This is the story that each of us constructs about who we are in the past, present, and future. This is what we refer to when someone asks us to describe ourselves. When we ruminate, we manufacture a narrative of who we are.

Second, there is an “experiential” sense of self. This refers to our ongoing stream of experiences: thoughts, actions, perceptions. This is the content of consciousness. It includes self-talk, mental imagery, emotions as they are experienced—not the character inside the story, which is the narrative self, but the moment-by-moment experience before we fashion it into a story.

The third is the “perspectival” sense of self. This is the sense of being a consciousness that subjectively observes or experiences thoughts, feelings, and sensations. It is a background awareness.

Whenever we say “I,” we may mean any or all of these. We don’t often notice that in ordinary life we have these ever-shifting understandings of “I,” but looking at this schema, you can see that we do. All of these together, in a way, constitute what Buddhists might call the conventional self. They are always changing, and not, by Buddhist standards, actually findable as “Me” with a capital “M.” Buddhism would say that these kinds of experiences are not, by themselves, the root of our problems. The root is deeper: it’s an innate sense of an “I” that is real, solid, enduring, and “me,” and that we believe we can find somewhere in or around our minds or bodies.

Dharma students meditating at Kopan Monastery, Nepal, December 2016. Photo by Laura Miller.

Mandala: How do mindfulness practices impact the self, when the self is categorized in these Western ways?

Lindsley: Researchers are finding that negative self-assessments and negative interpretations of events play a big role in a lot of emotional illnesses, and almost all of this is self-referential, meaning our interpretations—which cause us pain and even ravage our lives—are almost always related to how we see ourselves. As a result, these therapies target the narrative self: they work to change unhelpful and probably inaccurate stories about who we are. Mindfulness plays a central role. Instead of trying to counteract painful thoughts or feelings, mindfulness changes how we experience them. We become aware of negative memories, feelings, or thoughts, we watch them come and go, and we learn to accept them in a non-judgmental way as just passing experiences. So the experiences still happen but aren’t problematized. This actually alters the narrative self. It takes away its teeth. And psychological outcomes improve.

Mandala: Does that really work?

Lindsley: Yes, because whenever we experience a distressing event, how real, or maybe how relevant, we perceive it to be affects how much we suffer. By perceiving what happens as a mere mental event, and not tying it into a bigger story, such as “this is why my life can never improve,” and not ruminating about it, we are not so deeply impacted. Some people call this “decentering.” With decentering, painful thoughts or feelings are not seen as necessarily valid reflections of reality or “myself.” There is a broader perspective. And the thoughts or feelings are defused; we see ourselves “thinking” instead of being the thought. We can step away from the pain our thoughts cause. It works. So decentering is one of the main things people learn in therapeutic mindfulness practices.

Decentering can be described as a move away from the narrative self toward the experiential or perspectival self. This reduces the power of the narrative because people stop identifying it as “self.” What is self is widened. We observe thoughts rather than engage with them, shifting the locus of identity. You’ve likely heard of or done meditations like slowly eating a raisin, experiencing every moment of that taste, or meditatively walking, feeling the floor under your feet … these are ways of shifting identification from thoughts to experiences, or, to say it in another way, from the narrative self to the experiential self. In this broader experiencing, the narrative loses some of its power.

Mandala: What about the third sense of self—perspectival?

Lindsley: Some mindfulness exercises lead us to a perspectival sense of self, particularly meditations in which we develop awareness of being aware. This is seeing and identifying with the “observer” mind; a transcendent sense of self. This also works, but is perhaps a little less common in mindfulness-based therapies.

Mandala: If we just lived in the perspectival self all the time, would we be happy?

Lindsley: The point of mindfulness isn’t to always live in any one mode, but to be able to move easily among them. This weakens the narrative sense of self, which is often the source of mental or emotional problems. Being able to choose among these senses of self also gives people greater mental strength and resilience. The point is to not hold so tightly to our stories about who we are and what has happened to us and where we are going and so on. When people talk about being mindful and staying in the present, that’s one way of understanding what they mean. They can shift into an awareness centered more in experience than thought.

Mandala: How does that compare to the Buddhist goal of realizing the lack of an inherently existing self?

Lindsley: One of the goals of mindfulness is to move people away from identifying with a painful, destructive kind of self and toward identifying with a more adaptive self: going from the always-thinking narrative self to either the experiential or perspectival self.

This does help people. But it is far less radical than realizing the emptiness of that self. Buddhism would say that attributing an identity to any aspect of our experience is going to lead to suffering. So identifying with a more experiential or perspectival self is not liberation. It’s less suffering than identifying with, say, a ruminating, paranoid narrative self. But from a Buddhist perspective we are still making a mistake by finding a self in any of these places and identifying with it. The self we identify with, no matter how subtle, does not inherently exist, and believing it does is going to create suffering. Actually, modern cognitive sciences get that; they understand that the self as we conceive it is not a findable entity, it’s just a special kind of conceptual activity. But then Madhyamaka adds to that conclusion by making clear that this self goes beyond the conceptual; it’s a visceral, innate experience that is at the very root of our emotional life. Changing our ideas doesn’t change it because it runs so deep. We “know” intuitively that it is there—and we are wrong. Our minds actually create this self, like a hallucination, and then we believe in it. That leads to trouble. And we can’t really help doing it.

Mandala: I’m guessing that mindfulness alone doesn’t remove this misconception.

Lindsley: Exactly. The Gelug Madhyamaka meditation tradition that I’ve been studying counteracts the distorted sense of self by using deep analytical meditation, not just mindfulness. First, analysis generates a certain state of mind and then second, the meditator abides as stably as possible in that state. The idea is to bring to mind as clearly as possible the appearance we have of the self. That is called “the object of negation.” Then, we experience a contradiction between this appearance and reality because, using all the reasoning and logic we can muster, we come to see that what appears to our minds is not findable where we suppose it ought to be. We apprehend an absence, essentially, where we expect to find this self we believe we have. Then we abide in that feeling of not finding. After the meditation, the habitual sense of self will return, but over time the contradiction fosters increasing doubt about the self being what we think it is. By repeating the meditation again and again, an understanding develops and deepens. We start to see that the self we perceive is a kind of hallucination, and we stop believing in it. We still exist! But the self does not exist in quite the way we believe; it is not self-existent, independent, partless, permanent, and so on. We are told that this distorted sense of self will eventually disappear altogether and we won’t be bothered by it anymore. Wouldn’t that be amazing?

In a Tibetan gompa, a meditation cushion awaits an occupant. Nepal, December 2016. Photo by Laura Miller.

So you can see that the Gelug approach is different from mindfulness, and so is its result. The Gelug method seems to be able to eliminate our distorted conception of the self, not just help people create a more adaptive sense of self. An over-focus on mindfulness to improve well-being obscures this traditional Buddhist method for confronting our habitual relationship to self and leaves untouched its potential for ending suffering. It just moves the attribution of self from the story, the narrative self, to another part of the self, the flow of experience or the awareness. But it still ascribes “self” or “I” to those things. That’s because it doesn’t offer any counteracting force to weaken or remove this false apprehension. Instead of saying “I am my story,” we say “I am these sensations” or “I am this awareness of the passing flow.” But the mistake, the hallucination of “I,” is still 100 percent there. Some people imply that mindfulness leads practitioners to seeing through the illusion of self, but I doubt this could be true: the problematic self that we believe in so heartily has not been identified or fully countered.

Mandala: Are you saying mindfulness is not so good?

Lindsley: No, no, don’t misunderstand me. Mindfulness can be life-changing for some people. Greater control over attention, more flexibility in responding to emotions and events, and more perspective in our relationship to concepts are all demonstrably useful therapeutic tools. Mindfulness encourages people to be with experience differently and that can be tremendously helpful. And it has been shown to reduce all sorts of symptoms of common clinical issues.

Mandala: What do you see as the way forward?

Lindsley: I think there are reasons to consider expanding the study of meditation-based therapies, and their effects, to include the Buddhist understanding of self. The Gelug practice I’ve described may not be for everyone. But it could help some people. It may also be possible for mindfulness techniques to address the Buddhist notion of a false self more directly by encouraging a reduced identification of any aspect of the body-mind as the self. Care needs to be taken; there are people who might be harmed by practices that undermine whatever sense of self they have. But it seems that for some people, deepening their understanding of the lack of a truly existing self could make them happier and perhaps promote adaptive qualities like altruism. After all, if attributing “self” to ever-evolving experience creates suffering, doing less of it should reduce suffering. That would have to be tested, so pulling these meditations into social science research makes sense. I believe that science can open itself up more to examining Buddhist concepts; they should not be dismissed as just religious ideas. They are testable. Mindfulness came from Buddhism, after all, and is now widely used in secular therapeutic contexts. Stopping believing in a hallucinated self may also be profoundly therapeutic.

I also suspect that mindfulness-based therapies could indirectly undermine the belief in a truly-existing self. As psychology looks for explanations of why or how meditation helps people, I think seeing self-grasping as a spectrum having various levels could be useful. Mindfulness may not uproot self-grasping, but it may loosen it to some extent—moving people along that spectrum. In other words, just the act of moving the sense of self from one domain of experience to another may give people some insight into the process of self-attribution, thereby lessening self-grasping. This could contribute in some cases to the positive outcomes from mindfulness we now see.

My hope is that psychology can take this Buddhist concept of no-self more seriously and really consider its implications for human suffering. If that happens, there can be more study of how meditations that deconstruct the innate sense of self can help people. That’s what I would like my work to lead to.

Jacob Sky Lindsley teaching meditation as part of the public program at Maitripa College, March 2016. Photo by Marc Sakamoto.

Learn more about Buddhist meditation and study by visiting FPMT’s education programs at https://fpmt.org/education/programs/.

Mandala is offered as a benefit to supporters of the Friends of FPMT program, which provides funding for the educational, charitable and online work of FPMT.

1. Madhyamaka means “middle way” in Sanskrit. It refers to a centrist view of selves and other phenomena, neither eternalist nor nihilist, in which their existence is not substantiated by any eternal essence, but neither do they have no basis for existing at all. They exist by way of dependent origination. In other words, Madhyamaka philosophers propound the Buddha’s ultimate view of reality: phenomena, including selves, exist conventionally but are empty of inherent existence.

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.Look at modern society. Many people put themselves down; that’s their worst problem. You can see this everywhere in the world; people put limitations on themselves, on their own reality.