- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

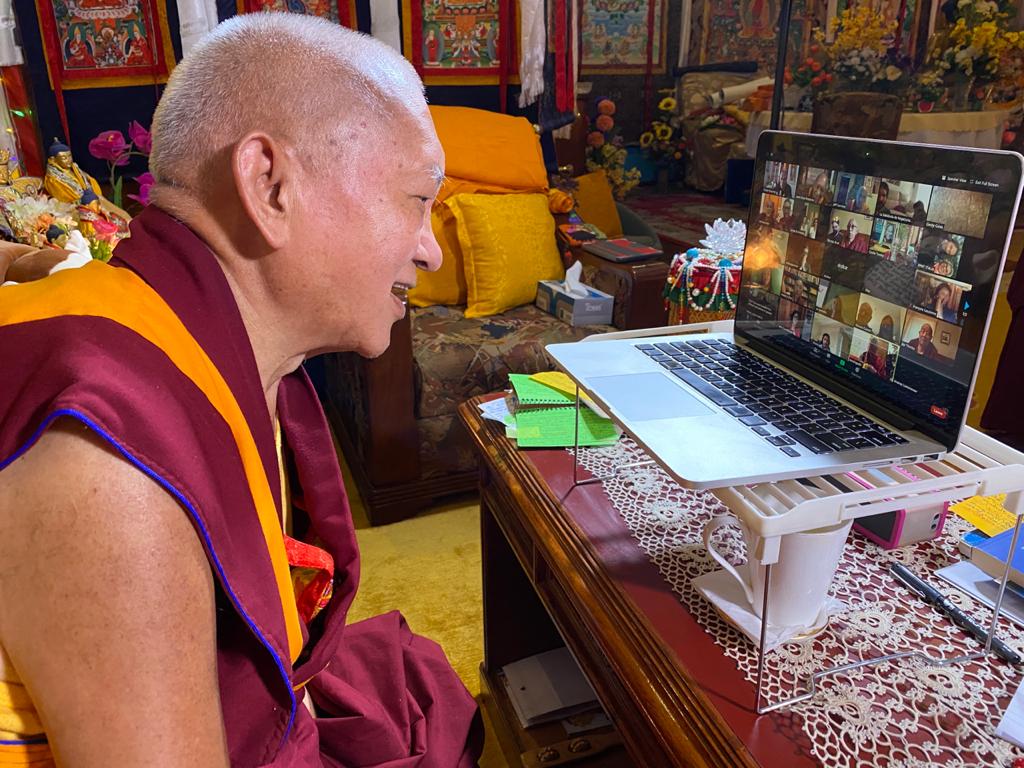

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

I hope that you understand what the word ‘spiritual’ really means. It means to search for – to investigate – the true nature of the mind. There’s nothing spiritual outside. My rosary isn’t spiritual; my robes aren’t spiritual. Spiritual means the mind and spiritual people are those who seek its nature.

Share

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

16

Memorization: Beneficial Exercise for the Mind

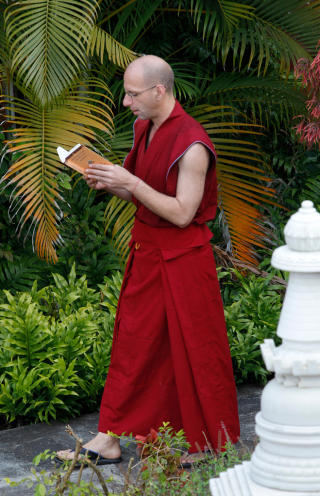

Monks working on memorization at Sera IMI House, Bylakuppe, India, November 2013. Photo by Sandesh Kadur|www.felis.in.

Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter), an American monk who just finished his seventh year of study in Sera Je’s geshe program, is a top memorizer and debater. In August 2013, he was one of 16 from his class of 118 chosen to participate in the rik chung debate held at Sera Je Monastic University in South India, a tradition instituted in the 17th century by Desi Sangye Gyatso, the regent to the Fifth Dalai Lama. In February 2015, Ven. Gache received the top award in the lo gyü chenmo (the Great Memorization Exam) at Sera Je Monastery, having committed to memory 873 pages.

Mandala asked Ven. Gache to discuss the history and role of memorization in monastic education and to share memorization tips to help lay students build their own skills.

In his biography of his teacher, Khedrub Je claims that Lama Tsongkhapa would memorize an astounding 17 folios (34 pages) of Buddhist text per day. Two natural reactions to this statement might be, “Is that even possible? It must be exaggerated,” and “Is that really a constructive use of one’s time and energy?” Without giving direct answers to these questions, I would like to respond first by describing a little bit about the place of memorization in Buddhist practice, both historically and today, and some of its potential benefits.

Ven. Tenzin Gache reciting from memorization during the tsog sag, Sera Je Monastery, India, August 2013. Photo courtesy of Ven. Gache.

Memorization has played a central role in the Buddhism’s saga since its earliest days. For the first few hundred years, the sutras and their commentaries were not written down. Monks and nuns would work together to keep these discourses in memory, orally passing them on to the next generation. In the First Council of Arhats shortly after the Buddha’s passing [also known as the First Buddhist Council, c. 550-450 BCE], his attendant Ananda recited from memory the entirety of the Sutra Pitaka [the collection of sutras], while another monk, Upali, recited the discourses on vinaya [monastic discipline]. Even after these discourses were committed to paper, memorization remained a standard practice in the monasteries and nunneries of India. The great scholar-practitioner Acharya Vasubandhu [c. 4th century CE] is said to have maintained a yearly ritual wherein he would sit upright for several days, gradually reciting all of the texts he had memorized in a bathtub of oil to keep himself awake. More recently, Geshe Rabten [1921-86 CE] observed a similar yearly ritual, but without the oil.

Memorization of the sutras and their commentaries is a standard monastic practice in all Buddhist countries, but here I will focus mainly on its expression in my own monastery, Sera Je, one of the three great Gelug monastic universities now located in South India.

Memorization in the Monastic Curriculum at Sera Je

Memorization is a significant part of a monk’s daily schedule, and mainly serves three purposes: memorizing philosophical texts for debate, memorizing prayers and rituals, and memorizing practical, advice-oriented texts. Each monk is free to choose how much he emphasizes any of these three.

Philosophical Texts

Memorization at Sera Je is an integral part of a greater study program that heavily emphasizes debate. In this context, memorization does not become a mere rote ritual, as a monk is expected to also be able to give a detailed explanation of the meaning of a text and defend his arguments against a barrage of criticism.

The discipline of most khangtsen (monastic colleges, or, houses) requires a monk to rise before dawn and recite new material for at least an hour. When there is no morning debate, many monks will continue until lunchtime. In the evening, monks review this material until close to midnight. During holiday breaks, many monks will stay in “memorization retreat,” reciting full-time.

The best memorizers will memorize entire texts such as Lama Tsongkhapa’s Essence of Eloquence, Haribhadra’s Clear Meaning Commentary, and several of Sera Je’s textbooks composed by Jetsün Chökyi Gyaltsen. Others will focus only on the definitions, divisions and key passages. These texts are often terse and confusing, and will only gradually unfold their meaning through prolonged reflection and debate.

At debate, which can last up to six hours a day, one cannot carry a book, so all debating must be done from memory. Often a monk will initiate a public debate with a quote from a text, prompting the defender to correctly identify the source and context. If he cannot answer, the crowd will yell “Chay!” (“Speak!”) until he can. If he is stuck, the questioner might give a few more words from the quote. Later on in the debate, the questioner is free to give quotes to support his argument, but is expected to recite them from memory. If he simply says, “It says something like this in that text,” he may meet with laughter.

Prayers and Rituals

Pujas and group prayers are a daily complement to the debate program. Monks cannot carry prayer books, so they must recite these prayers from memory as best they can. Before even entering the debate program, one is expected to memorize an 80-page prayer book and recite parts of it in a group before the abbot. The monks most serious about chanting will enter the don zang (good reciter) group, later advancing to kä zang (good voice) and finally to umdze (head chanter). The umdze must have the better part of a thousand pages of material memorized and ready for fast-paced reciting. At the tantric monasteries of Gyuto and Gyume, this second aspect of memorization is more heavily emphasized, and all monks must memorize the liturgy that includes the self-generation and self-empowerment of several tantric deities.

Practical Texts

Memorization of practice-oriented texts is not officially part of the study program, though the monastery does recognize monks who have memorized certain of these texts such as Shantideva’s Entering the Bodhisattva Deeds [also known as Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life], Nagarjuna’s Six-Fold Collection of Reasoning,1 and the Five-Fold Dharma of Maitreya.2 Some monks will recite these texts in their spare time such as when walking to and from debate.

The monastery utilizes various skillful methods to encourage monks to memorize. Written memorization exams on the yearly study material are a standard part of the course syllabus, and monks can also opt to take special memorization exams on entire texts. The lo gyü chenmo, “Great Memorization Exam,” is a yearly tradition in which any monk can come and offer an oral exam of whatever material he has prepared. A monk will bring one or more books and place it before a geshe who will proceed to read passages at random. The candidate must continue reciting where the geshe leaves off. The geshe will continue in this way until he is or isn’t satisfied that the candidate really has the material in memory. A scorekeeper sitting behind the geshe keeps track of how many pages the candidate can offer. Several months later, the study deans announce the total scores, awarding a prize to those with the highest totals.

If a monk has memorized an entire text, he is also eligible to perform tsog sag, “merit accumulation,” where over the course of a month he will gradually, rhythmically recite part of the text before the community during the tea breaks in pujas.

Even after completing the study program, the top scholars must continue to memorize: the gekyö (disciplinarian) must recite the monastery rules and the khenpo (abbot) must recite a variety of long texts such as the sojong (monastic confession) ceremony and its associated sutras.

Benefits of Memorization

One common criticism people raise about memorization is that it is just words. It’s true, they are “just words,” however, the words we say and hear have a powerful effect on how we think, feel and behave. For many of us today, popular songs, movie clips and catchphrases continuously replay themselves in our conscious and unconscious layers of mind, subtly influencing our mood and belief system in ways we may not notice until we try to meditate and find our mind is like Times Square or worse.

Ven. Tenzin Legtsok memorizing at Sera IMI House, India, November 2013. Photo by Sandesh Kadur|www.felis.in.

As the content of popular culture mostly encourages attachment, worry or violence, becoming mindful of what we consume is sound advice for bringing our mind into a more peaceful space. Another method to counter these negative influences is to fill our mind with more constructive pathways. Cultivation of positive mental states like compassion, patience and introspection is essential, and memorizing texts and prayers that encourage these states helps to enhance them and ensure that they become more habitual. In fact, the Tibetan word for meditation, gom, literally means “to habituate.” First we learn something and commit it to memory, then we reflect on it and consider its meaning. Finally, we call it to mind again and again, familiarizing with its message and gradually deepening our understanding.

Vasubandhu explains that the lineage of the Buddha’s teachings is twofold: the teachings of scripture and the teachings of realization. Initially, generating realizations in our mind-stream is difficult, especially if we are strongly conditioned to contrary forms of thought and behavior. However, we can immediately participate in the scriptural lineage if we memorize texts and reflect on their meaning. This will place strong imprints on our mind that will gradually develop into deeper realization. Because past masters have composed and recited these same texts and developed these realizations, the mere words are also thought to carry an energy that will purify and ripen our mind-stream. Much like prostrations and mantra recitation, memorization can be a powerful preliminary practice before more advanced meditation.

Dharmakirti points out that while physical development is limited – even Olympic athletes will reach a limit in how far they can extend their jump – the mind’s potential is limitless. Athletes train the body through exercise. Memorization is an exercise for the mind, and much like a physical one, is something in which we can practice, improve and eventually excel. This process enhances and sharpens the mental faculties, which we can then apply to analysis and meditation. Whereas neuroscientists once believed that the adult brain could not develop new neurons for memory or otherwise change its hard-wiring, advances in past decades have firmly overturned this dogma.3 A significant body of study also suggests that memory training may reduce the risk of dementia in old age.4

Rather than leading to dry, uninspired repetition of old facts, memorizing texts allows a student or teacher to be more fully creative. At debate, a monk who can picture the entire text can form connections and penetrate its layers of meaning, authoritatively dispelling wrong conceptions and groundless assertions. A teacher who can recite relevant quotes and call upon ideas from a variety of sources will impress upon students the profound depths and vast breadth of Buddhism’s scholastic, practical and poetic traditions. Memorization is key element in an immersion into these traditions that will gradually pacify and transform those willing to make the effort.

Watch “Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter) at Rik Chung Ceremony, August 4, 2013″ on YouTube.

Conclusions and Where to Begin

When I was at high school in the United States, a visitor who had memorized Paradise Lost performed for our senior English class. We found the performance impressive, even amusing, but many of us wondered to ourselves why anyone would spend so much time on a seemingly trivial activity. With the advent of calculators and computers, and especially more recently with smartphones and iPads, the art of mental aerobics such as memorization seems obsolete. Why calculate in your head when you have a calculator and why memorize when you have a digital encyclopedia? Similarly, modern Dharma students might ask whether the monastic tradition of memorization is important in Western Dharma centers.

If the value of memorization lay purely in the recollection of specific facts, we would be better off keeping our gadgets. I hope this article has suggested that memorization might mean much more. The intention behind memorization is not to become a warehouse of old facts, but to actively train and develop your cognitive abilities and familiarize yourself with constructive ways of thinking. Many of us read a passage from a Dharma text and think, “I must remember this point,” but how often do we forget our initial insight and inspiration? Through memorizing inspiring texts, we continuously call them to mind, habituating ourselves to the positive attitude they convey. Through memorizing difficult texts, we gradually begin to penetrate their hidden significance, while integrating the message into our being in a way that we can start to feel, “This is a part of me.” If we truly are the summation of what we think and believe, we would be prudent to familiarize with eloquent, uplifting and sagacious sayings rather than much of the superficial relics of pop culture that bombard us if we tune into TV and the internet.

If you are wondering where to begin, a good place to start would be to memorize your daily commitments or the teaching prayers at your local Dharma center. Practically oriented verses like Three Principal Aspect of the Path, Lines of Experience, and 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas are also good for daily recitation. Serious students might consider memorizing the root texts or commentaries they are studying. Young students who start now will build a talent that will increase over time and enhance their development. Older students will help keep their minds sharp and memory fresh. In time, memorization can become an element of Western Dharma practice, just as it has been in Buddhist communities in all times and places.

- Set aside some time each day, preferably early in the morning for new material and late in the evening for re-reciting what you memorized in the morning.

- Sit up straight or gently pace in an open area, preferably somewhere where your recitation won’t disturb others.

- Before memorizing, “warm-up” with recitations like Praise of Manjushri, Prayer to Achieve Inner Kalarupa, and Chanting the Names of Manjushri.

- Start by reciting one half a line. When you can recite this five times without looking at the book, recite the second half. Then recite them together. Then do another line. Then add the two together. Continue in this way, gradually adding to the total, until you finish a verse or a few lines of prose. If you are able, start again with a second verse. Then recite the two together. Over time, you may be able to increase the number of verses you can do in a day

- Once you have something committed to memory, continue to recite it once or more a day until it becomes stable. Then gradually decrease your recitation to once every two days, three days, etc. If you have something very well memorized, you may only need to recite it once a month, but getting to that point will take time.

- During your daily activities, minimize distraction and stimulation, especially loud music. Just as when meditating, keeping your mind clear will enhance your practice sessions.

Some Additional Suggestions (optional):

- Before beginning to memorize something, simply recite it every day for one month.

- When you have memorized something well, stop reciting it for some time. When you start again, it will take a little time to bring it back, but it will become more stable.

- Ask a friend or teacher to examine you on what you have memorized – preparing for an exam can enhance your focus.

Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter) is an American monk living at Sera International Mahayana Institute (IMI) House in Bylakuppe, India, and studying at Sera Je Monastic University. Mandala is looking forward to publishing regular features written by Sera IMI monks about monastic life and practice.

In case you missed last month’s online feature, “Jeffrey Hopkins’ Transmission of Honesty,” you can read it now. If you like Mandala’s online features, consider becoming a Friends of FPMT, which supports our work as well as the education programs of FPMT.

1. Root Wisdom, Finely Woven, Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness, Dispelling Objections, Sixty Stanzas on Reasoning, and Precious Garland.

2. Ornament for Clear Realization, Ornament for the Mahayana Sutras, Differentiating Middle and Extremes, Differentiating Phenomena and Pure Being, and Sublime Continuum.

3. See, for instance, William Skagg’s “New Neurons for New Memories” in Scientific American Mind September/October 2014; or Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz’s excellent The Mind and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force, Harper Perennial, 2002.

4. See “Memory in Old Age Can Be Bolstered” in Scientific American Mind November 2012; and “Promising Strategies for the Prevention of Dementia.”

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.The sun of real happiness shines in your life when you start to cherish others.