- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

Without understanding how your inner nature evolves, how can you possibly discover eternal happiness? Where is eternal happiness? It’s not in the sky or in the jungle; you won’t find it in the air or under the ground. Everlasting happiness is within you, within your psyche, your consciousness, your mind. That’s why it’s important that you investigate the nature of your own mind.

Share

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

12

Dhi! Ven. Tenzin Namjong on Debate, Study, and Life at Sera Je

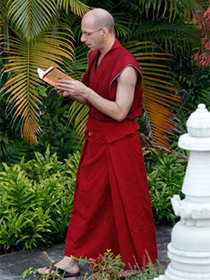

Ven. Tenzin Namjong.

Photo by Abhijeet Kumar.

Ven. Tenzin Namjong (Matthew Pasion) was born in 1977 in Hawai’i, USA. He ordained in 2007 and is currently in the tenth year of the geshe studies program at Sera Je Monastery in South India. This interview brings together a series of email conversations he had with Mandala associate editor Donna Lynn Brown.

Ven. Namjong, how did you meet the Dharma?

I studied philosophy at Princeton. I thought I was going to do a Ph.D. in philosophy, but I got disillusioned because academic philosophy seemed to have lost the big picture, meaning how we should live our lives. So I went to work in finance. That wasn’t very fulfilling. I got interested in yoga and, through yoga, meditation. Through that I got into Buddhism. What resonated with me in Buddhism is that there is this rich philosophical tradition, but all of it is about how we should live our lives.

I started meditating and reading different books from the Eastern spiritual traditions when I was living in New York in the early 2000s, then I left my job and went traveling in Asia. My first stop was Japan and I stayed in a Zen monastery. Then I went to Thailand and did a vipassana retreat. In India, I did Ven. Antonio Satta’s vipassana-Mahamudra course at Root Institute. That was where I first dipped my toes into the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. His Holiness the Dalai Lama was teaching during Losar in Dharamsala, and so I went there and received teachings on Words of My Perfect Teacher—a Nyingma lamrim text that gives an overview of the path to enlightenment. I went back to the US, and was doing vipassana, which I continue to love, but reading Shantideva and other Mahayana texts. I returned to India thinking I would study Tibetan and Sanskrit so I could do a Ph.D. in Buddhist Studies. But the more I studied and practiced, the stronger the desire to ordain become, so after two years in Dharamsala, on the advice of my teachers, I went to Sera Je. I ordained the day after I arrived.

At Sera, you have to study in Tibetan. How has that gone?

Prior to Sera, I had only studied Tibetan for nine months. When I got to Sera, my plan was to use one year to prepare, including improving my Tibetan, and then start the geshe studies program the next Losar. This was in 2007. My teacher there said, “Yes, that’s OK. Take this year to study Tibetan.” Then one day I went to a puja where we read the Kangyur and I saw a monk—it was hot—fanning himself with the pages of the sutra. When I met my teacher after I said, “I can’t believe what I saw in this puja. There were people fanning themselves with the Dharma!” And he responded, “OK. I think you should start debate.” Related or not, that’s how it happened. And so I started in June of my first year there. At that point, I had not even been learning debate, just Tibetan.

Fortunately, one of my housemates, a New Zealand monk named Jampa Chöpel, taught me the basics of debate. I had read the late Daniel Perdue’s book—Debate in Tibetan Buddhism—but that’s different from actually doing it. One conversation I remember … You know that objects of knowledge include permanent phenomena and impermanent phenomena, right? So Jampa asked me, “The subject ‘object of knowledge’ itself, is that permanent or impermanent?” I was stumped. I just sat there thinking. He said, “You can’t just sit there pondering! Answer whatever you think.” I said, “Well, OK, impermanent.” And then he said, “No, it’s permanent …” There is an axiom: if a phenomenon has both permanent and impermanent parts, it is permanent. Working with him like that is how I got up to speed.

I started going to debate and my Tibetan was not very good, but actually, I believe it improved more by going to debate than if I had just stayed home and studied.

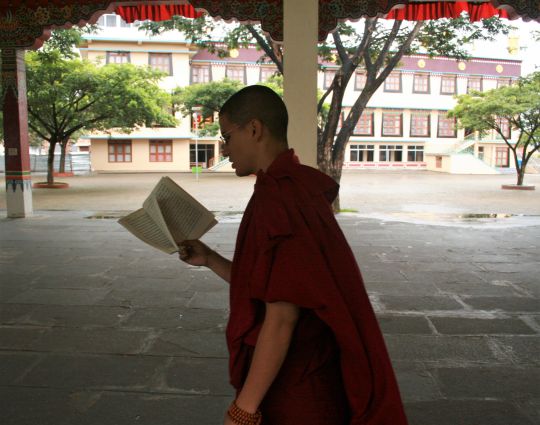

Ven. Namjong memorizing a text, Sera Je Monastery, India, September 2009. Photo courtesy of Ryan Matsumoto.

What is your schedule at Sera?

The academic year is divided into so-called “on sessions” and “off sessions.” During the “on sessions,” there is debate in the morning from 9-11 a.m. and then again in the evening from 6-10 p.m. During the off session, there is no morning debate and in the evening, debate runs from 6-9 p.m. In the morning, before debate, and at night after debate, we memorize and recite texts. Reading textbooks and commentaries is usually done in in the afternoon, or after morning and evening memorization. On top of that, there are often pujas and group prayer sessions that start at 5:30 a.m. There aren’t pujas every day, but sometimes there can be three or four. Each day, I try to do a bit of meditation and slowly go through the practices that Lama Zopa Rinpoche has given me, but the emphasis is on study. I heard that in Tibet, monks weren’t allowed to take initiations or even go to a lamrim teachings until after they graduate. That has changed in India, but that mind-set of study being foremost is still there. When I tell people we’re studying so long, up past midnight and waking up at five, they say, “What? That’s a monastery? I thought monks were more peaceful.” We’re trying to radically transform the mind, and difficult circumstances allow for more growth and change. I try to remember that when I’m feeling, “Oh my gosh, this is so difficult.” The geshe studies program lasts maybe twenty years, but samsara is beginningless—and if we don’t do the work to gain liberation and enlightenment, it will also be endless!

What role does debate play in your program?

By far the main avenue of learning at Sera is debate. Some people are surprised to hear that we have only two or three hours of classes per week. But we debate several hours a day. As we advance, there is even less class time. Once you know how to study, you read a text and then settle your doubts on the debate courtyard rather asking a teacher to tell you. It was a bit of a change for me to grasp that listening to the teacher is not so much to receive an answer as to get more questions, more doubts, so there is more to debate. That’s part of the reason we have twenty years. For example, for some questions, I can see there are good reasons on both sides. So I’ll debate these questions over and over, from both sides of the issue, not necessarily trying to come to one resolution—just experiencing all the arguments.

Do you like debate?

I don’t know about always liking debate, but it’s very beneficial for my mind. His Holiness the Dalai Lama emphasizes how we need to be 21st-century Buddhists: not merely relying on scriptural quotations, but using reasoning to establish the veracity of the teachings. He often quotes the Tattvasamgraha: “Like gold [that is acquired] upon being scorched, cut, and rubbed, my word is to be adopted by monks and scholars upon analyzing it well, not out of respect [for me].” Intense debate is the means by which we gain clarity about the teachings—particularly the four noble truths, selflessness, and emptiness. And years of debating key scriptures and concepts generates conviction. Then this conviction creates tremendous energy for practice.

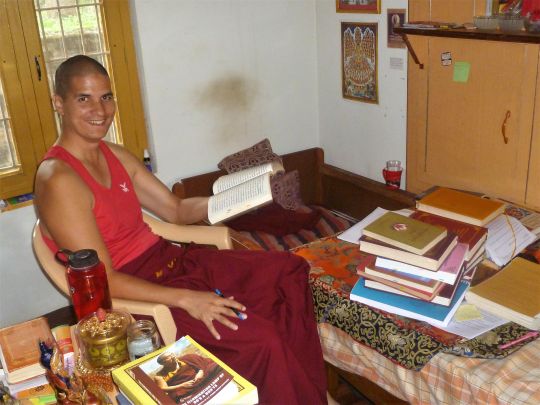

Ven. Namjong surrounded by books while studying for debating exams in his room at Sera Je Monastery, October 2015. Photo by Ven. Tenzin Legtsok.

How do you think debate leads you to knowledge and realization?

All suffering comes from the mind, especially from distorted views about reality. If we discover the truth of reality, we can abandon the distorted views at the root of our suffering. Our senses are not accurate about hidden phenomena, and some of the key principles in the Buddha’s teachings—impermanence, selflessness, emptiness, past and future lives, the four noble truths, and karma—are hidden phenomena. These have to be realized for the first time by a reasoning consciousness. The purpose of debate is to develop our reasoning skills so we can realize these. You can’t just repeat, “All phenomena lack inherent existence, all phenomena lack inherent existence” and get a realization of emptiness! You have to see your own innate view and then use reasoning to discover what is really true.

Debate is analytic meditation in action. It isn’t primarily about defeating an external opponent. Rather, we need to recognize and refute our mistaken ways of thinking using reasoning. The answer in and of itself is not that helpful if you haven’t arrived at it through first identifying and then refuting the wrong view. The late Choden Rinpoche remarked that clapping the hands once on the debate courtyard (which is done every time a question is asked) has more benefit than three months of retreat. I think this is because studying and reflecting on the Prajnaparamita has so much benefit, as is explained in the sutras themselves. I have also heard that some past masters got their first realization of emptiness right in the middle of a debate, so the debate process definitely helps us to recognize and refute our wrong views, the most important one being the view grasping onto true existence.

Can you describe how debates proceed?

Dhi!

A debate starts with an invocation: “Dhi, jitar chöchen.” “Dhi” is the seed syllable of Manjushri, the buddha of wisdom. One standard explanation is that this means, “Dhi: in just the way Manjushri investigated the subject.”

There are two roles in a debate: the defender and the questioner. The defender has to put forth positions, and the questioner’s job is to make the defender contradict himself or abandon his earlier positions by showing that they give rise to faults or undesirable consequences. The questioner does this by starting from the defender’s thesis and then “throwing” a series of logical consequences that would seemingly follow from the earlier assertions. The questioner, appealing to scriptural passages, generally accepted tenets, and even common sense, tries to take these consequences to a point where the defender cannot maintain his position.

The questioner starts the debate. Often he gives a fragment of a quote. The defender has to then identify where in the root text, commentary, or textbook the passage is from, and supply the rest of it. He is then usually asked to reconstruct the outline of the text. At first, I was confused by the emphasis Tibetans place on learning outlines. Now, I see the utility: it provides a way to quickly run through the main points of the text. Listing the outlines is a scanning meditation on the whole text.

Usually, the initial quote will be illustrative of a larger point. For example, if we are debating about bodhichitta, the questioner may quote the Abhisamayalamkara: “Mind generation is the wish for compete enlightenment for the benefit of others.” After the defender goes through the outline, the questioner will set the groundwork for the debate. One common way to do this is to ask the defender to posit the definitions and divisions of the topic. Then the questioner may try to determine the “limits of pervasion.” A pervasion is a logical entailment: if “A” then necessarily “B.” The questioner will ask for the pervasions of various phenomena: how they interrelate. Once a pervasion is agreed to, the questioner will try to find a counter-example to show the defender has erred; then the debate goes on …

What is easy in debate? What is hard?

The questioner has a lot of freedom to decide where the debate will go. Defending is more difficult because the questioner sets the agenda, so he can direct the debate to where he feels comfortable. The defender is at the mercy of the questions. But one good thing about being the defender is that, if you don’t know the answer, you can just give one of the four responses and it is up to the questioner to prove the point. Sometimes, if you haven’t studied so much that day, and you’re asked a question you haven’t really thought about, you can just answer however seems reasonable at that moment, and see what kind of logic, reasoning, and quotes the questioner has. Sometimes one day I’ll answer one way; another day, I’ll answer the other way, just to see what reasoning people bring to the table.

Could you lead us through a short debate?

Sure. A basic example goes like this:

- The questioner says: “It follows that if something is a color, it necessarily is white.”

- The defender has only four standard answers: “Yes,” “Why,” “The reason is not established,” and “No pervasion.” If the defender agrees with the statement that if something is a color, it is necessarily white, he will reply “Yes.”

- The questioner will then try to posit something that is a color and not white. He might say, “Take the subject red. It follows that it is white.”

- The defender has the same choice of answers as before. If he agrees, he can say “Yes.” But it is common sense that red is not white. If the defender asks, “Why?” then the questioner has to supply a reason that would establish that red is white. Since the defender has already agreed that whatever is a color is necessarily white, the questioner can say, “It follows that the subject red is white because of being a color.”

- When reasons are given, the defender has two standard answers. If he denies that the subject, i.e. red, is the predicate, i.e. a color, he will respond, “The reason is not established.” The questioner will then have to give further reasons why red is a color.

- If the defender agrees that red is a color, but whatever is a color is not necessarily white, then he will answer, “No pervasion.”

- But that pervasion was agreed to by the defender earlier in the debate, so now if he answers, “No pervasion,” he will lose his earlier position.

- If that happens, the questioner will say, or more often shout, “Tsar!” while slapping the back of his right hand on the palm of his left hand. Tsar means “finished,” and here it signifies that the defender’s original assertion has been defeated.

It sounds more like a logic game than Dharma!

At the beginning, one of the main goals is to teach technique, and this is easier if it is first done in relation to everyday objects like colors. So then it does look like just a game! But it would be a mistake to think that, because we use these same techniques to debate serious topics. This style of debate allows very sharp distinctions to be made. That helps to clarify important issues for both parties.

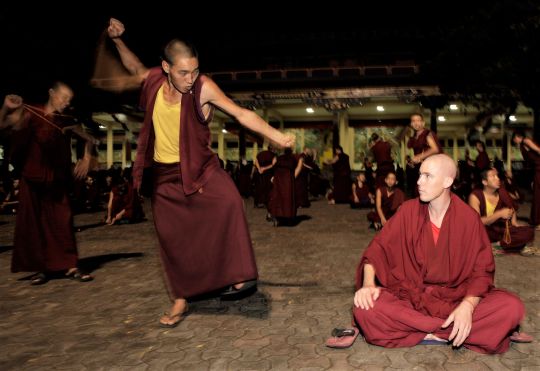

NIght-time debating at Sera Je. Ven. Losang Dargye (standing) and Ven. Jampa Khedrup (seated), November 2013. Photo by Sandesh Kadur.

Is it very competitive?

Especially the first several years—and even now for some people—being tsar (defeated) can be like the end of the world. “That’s not supposed to happen!” Because of that, some people defend more and more difficult positions because they don’t want to go against what they’ve already said. That kind of competitive, “I’m gonna show him” attitude declines over time. I’ve been here over nine years and now I find debate pretty comfortable. Where I still see some showmanship and competitiveness is in the winter debate session where the monks from Sera, Drepung, and Ganden all debate together. That can generate some fireworks!

Personally, when I’m debating and I realize I’ve made a mistake, I like to be upfront, and say, “OK, give me a tsar and let’s go down some more interesting avenues.” And I admit I can be a bit of a showman too. For example, even if your opponent gives the “right” answer, you can act shocked—like they have said the craziest thing possible. If the opponent isn’t confident in his position, he may start to doubt his position, which can make his answers deteriorate. Again, it isn’t just about the right answer. I think of debate as performance art. That makes it more fun. One time, a visitor to the monastery saw us debating, complete with all the clapping and pushing, and thought we were practicing kung fu!

It must be hard on the ego sometimes …

Once in the first year I was here, I was trying to hold a point, and someone listening said, “You don’t speak Tibetan very well. Why not?” How do you even respond to that? It was a real blow to my ego. Oftentimes the benefit of debate is just to watch how the ego plays its games. Some days I get totally crushed in debate. Even in my third year, there would be days when I would understand very little. And I would get a bit down, thinking, “I can’t believe I’ve been here three years and I’ve barely understood anything my debate partner said!” It’s good for us to see everything that’s in the mind. The lojong teachings talk about bringing unconducive circumstances onto the path. A lot of the learning is not even about the text, but going through an extremely difficult program and seeing how your mind reacts to different situations. And debate is really, really good for that.

When we debate, we have to watch our motivation. There is a tendency, after a debate when we go home, to look up different scriptural passages and think, “Oh, I really could have gotten him on this point!” We have to watch our motivation because the eight worldly concerns can come in, especially pride. Pride manifests as jealousy towards our superiors, competitiveness with our equals, and contempt for those we consider beneath us. For example, when we have our debate exam, they post our scores on a board along with our names for everyone to see. Then if we see someone score higher than us, even though we think we are “better” than him, the mind freaks out. For several years, as an antidote to this, I didn’t even go to look at the results, but it was no use because all my classmates would look me up and tell me how I scored anyway! There is a balance though: because we do have a certain level of pride, we will study harder when the results are public. If we are skilful, we can actually use the ego to overcome ego.

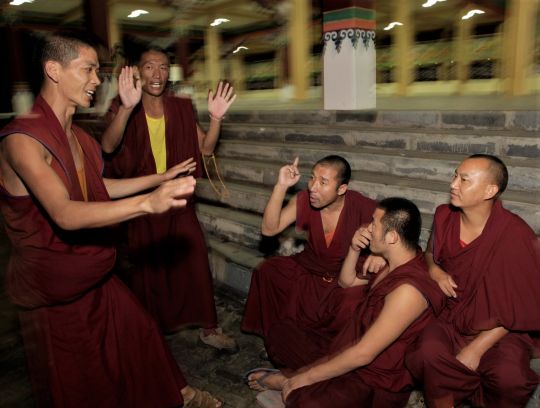

Tibetan monks at Sera argue a point during a night-time debate. (L to R) Vens. Ngawang Gyatso, Losang Nyima, Losang Gyatso, Losang Trinley, and one unknown, Sera Je Monastery, India, November 2013. Photo by Sandesh Kadur.

What are some of the ways debate has helped you?

First, I often read certain passages in my room and I think I understand what they mean. Then in debate, I see that the things I had glossed over, thinking I had understood them, were more complex than I thought. So debate forces me to go deeper into the text to penetrate the meaning.

Second, having to debate in public where I have to reveal what I know and don’t know pushes me to put consistent effort into studying. If any of us don’t keep up with the class, debate makes that clear to everyone. I find this helps me to fight laziness!

Third, some topics have good reasons for arguing either side; there are many points of contention. The previous incarnation of Kyabje Song Rinpoche said that if there are no divergent views, then there are no scholars. Debate helps me appreciate and value the different positions. And it forces me think about things from different angles, and consider questions that wouldn’t necessarily come to me if I were just studying on my own.

Last, being constantly confronted with things that I don’t know is the best antidote to pride. As it says in the Jataka tales: “A fool who thinks he’s wise is the real fool. A fool who knows he’s a fool is at least wise in that regard.” Discovering how little I actually know has been one of the best things for me. It has spurred me on to further inquiry, which will hopefully lead to more knowledge one day. You know, I can’t claim to have any understanding of the scriptures yet. But I can see that, thanks to the kindness of my gurus, debate really has benefited my mind and my practice.

Debate can be quite physical. Is that how you stay in shape and keep up your energy?

Although debate can get physical sometimes, generally it isn’t. What you may have seen with monks pushing and shoving is the exception, not the rule. Most debate sessions are just with one partner, and for that you are spending half the time sitting down answering anyway. Even when you are standing up, the clapping isn’t enough to make your heart rate go up. So I can’t call it exercise.

That said, I do consider it important to exercise. I’ve had my share of illness at Sera, so I try to stay in shape. There used to be a group of monks that would go jogging before dawn, and I joined them for a time. But then the abbot spoke out against it. I think it is mainly that the people in the surrounding areas think it is un-monastic. The abbot said that if monks want exercise, they should do prostrations, which will benefit the next life as well as this one. Since then I don’t jog, I do prostrations.

Nonetheless, I try to do other exercise as well, as the prostrations only work some muscle groups and I can only get my heart rate up so much by doing them. His Holiness the Dalai Lama emphasizes that we have to take care of our health by proper diet and exercise—taking long life initiations isn’t enough. Since time is a factor, I have been experimenting with high-intensity interval training. I can do a full workout in twenty minutes and then have renewed energy for my studies and practice. And I do it where only my housemates can see me, not lay people!

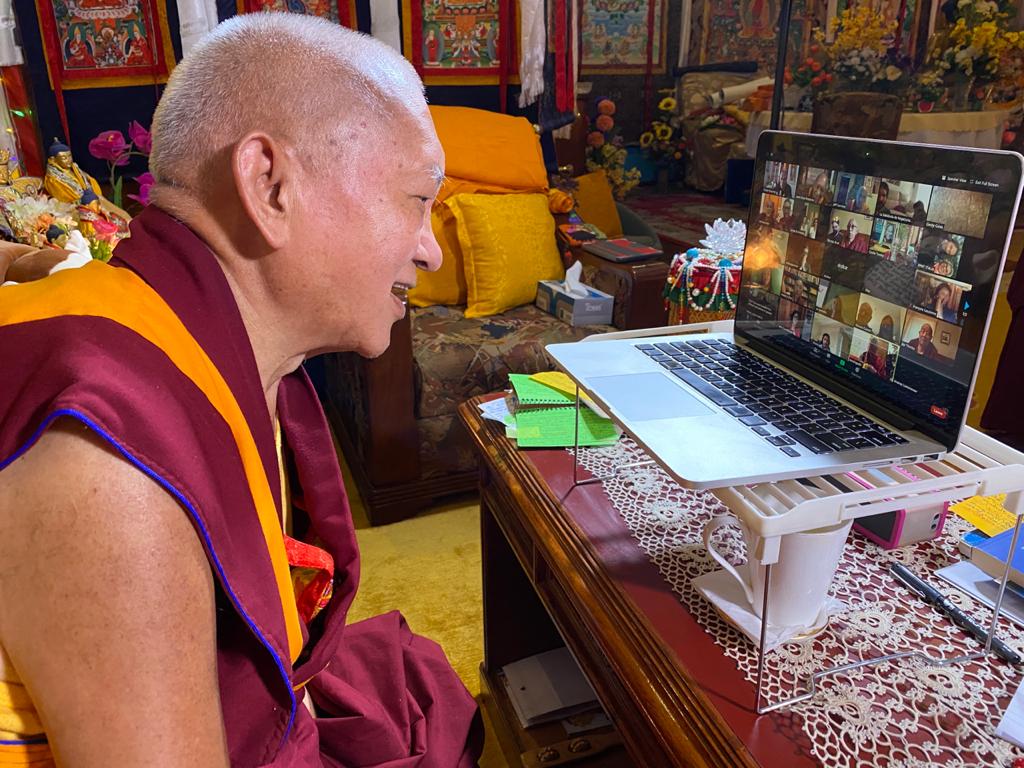

Lama Zopa Rinpoche giving advice to the Sangha staying at IMI House in December 2015 during His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s lamrim teachings at nearby Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. In the photo are (L to R) Vens. Tenzin Namjong, Tenzin Gache, Tenzin Namdak, Tenzin Legtsok, Tenzin Michael, Losang Jinpa, and Losang Tsondru. Sera Je Monastery, India, December 2015. Photo by Roy Harvey.

Is your long-term goal to finish the geshe studies program and then teach?

My long-term goal is to attain enlightenment for the benefit for all sentient beings! Medium-term, I’ll ask Kyabje Lama Zopa Rinpoche, because following the guru’s advice is the best thing, always. It seems I’ll continue studying at Sera for as long as I can. I’ve just finished my last year of the Prajnaparamita, where we study the Abhisamayalamkara, and then there’s four years of Madhyamaka. I definitely want to study and finish Madhyamaka. If the study goes well, I’ll be in a position to do many things: teach or translate or do retreat. From my side, I want to do retreat; I think that would be good for my mind. Also, since there’s a lot of interest in Buddhist philosophy in the West, and not too many teachers, I think teaching would be part of what I do, if people want to hear what I have to say! I consider myself very fortunate to have lived in a monastic community, so perhaps there is something I can do to help to build a monastic community in the USA for American monks who don’t have the inclination to come out to Asia. How about somewhere without snow in the winter? I’m conditioned to the Hawai’ian or South Indian weather! Anyway, the bottom line is, I’m continuing my studies and if things go well, I’ll be in a position to do a number of things to benefit the Dharma and sentient beings. Then whatever Rinpoche asks of me, to the best of my ability, I’ll do.

Sera IMI monks in the courtyard of IMI house at Sera Je Monastery, India, November 2013.(L to R) Vens. Gyalten Lekden, Tenzin Legtsok, Tenzin Gache, Tenzin Namdak, Jampel Tsering (child), Jampa Khedrup, Losang Khedrup, Tenzin Namjong, Gyalten Choklang. (The boy monk, Jampel Tsering, is Ven. Tenzin Namdak’s student and lives with the monks at Sera IMI house). Photo by Sandesh Kadur.

Learn more about the monks and nuns of the International Mahayana Institute (IMI), a community of Buddhist monks and nuns of the FPMT, at imisangha.org.

Mandala is offered as a benefit to supporters of the Friends of FPMT program, which provides funding for the educational, charitable and online work of FPMT.

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.Superficial observation of the sense world might lead you to believe that people’s problems are different, but if you check more deeply, you will see that fundamentally, they are the same. What makes people’s problems appear unique is their different interpretation of their experiences.