- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

Lama Zopa Rinpoche

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

16

‘Something to Rejoice In’: Geshe Tenzin Namdak In His Own Words

Geshe Tenzin Namdak. Photo by Deepthy Shekhar.

On May 8, 2017, after twenty years of study at Sera Je Monastic University, Ven. Tenzin Namdak, a registered FPMT teacher and native of the Netherlands, was formally awarded his geshe degree during a three-day ceremony that included public debate, recitation of memorized texts, and pujas. Geshe Namdak is the first Westerner to complete the full course of studies at Sera Je Monastery and also to sit for the final geshe examination there, a tremendous achievement.

Ven. Gyalten Lekden, who is in his fifth year of geshe studies at Sera Je, interviewed Geshe Namdak for Mandala in June 2017.

Ven. Gyalten Lekden: Thank you so much for the chance to interview you today, Geshe Namdak-la. Would you briefly introduce yourself?

Geshe Namdak: Well, “Geshe” I am not very used to yet! Anyway, I am Tenzin Namdak. I have stayed in Sera for about twenty years and studied a little bit, and based on that the monastery decided to give me a geshe degree.

You grew up in the Netherlands, where, according to the 2016 census, 68 percent of the population claim no religious affiliation. With that as your background, what was your own spiritual journey like?

You know, people in Holland are easy-going and open-minded. My parents were not really religious as such; they wouldn’t say they were Christian. When I was very young we sometimes went to church, maybe for Christmas or something, but that also disappeared after some time. So when I started looking into spiritual practice, I did not have any baggage, I was wide open.

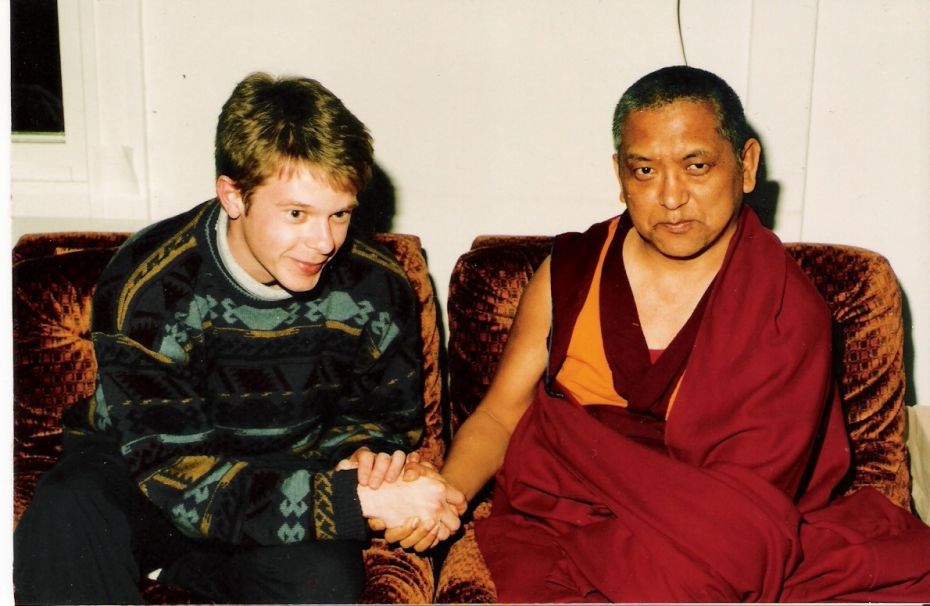

Before ordaining: Ven. Namdak with Lama Zopa Rinpoche in 1993 at Maitreya Instituut, the Netherlands. Photo courtesy of Maitreya Instituut.

When I started university, I began to generate more interest in Eastern philosophy. I had a martial arts background, first training in tae kwon do and then moving to less aggressive martial arts like kung fu and then eventually to tai chi. From there I generated an interest in Chinese medicine. At that time, I had already stopped going to parties, and the other things people normally do on the weekends. Instead, I spent my weekends studying Chinese medicine. This led me to a conference that had a variety of speakers. At that conference, Geshe-la, I mean Geshe Sonam Gyaltsen, who had just came to Holland, gave a talk about mental and physical health. I attended his talk and it was very inspiring. When the presentations finished, I went straight away to the stand of his particular organization, which was FPMT’s Maitreya Instituut, and I took a brochure.

You just finished your geshe degree, but before ordaining you completed your university degree in hydrology. Do you see some benefits of that secular study translated into your monastic study?

Growing up in the West, having an education, and working one year for the government on an environmental project—those all gave me a wide range of experience. If you want to become a monk, it’s good to have a little experience of ordinary life so you know what you are leaving behind. So from that point of view, I think , yeah, it isn’t wasted. It is beneficial to know what is going on in the West, and based on that, make the decision to become a monk, so then the decision is based in reality and not simply an idealistic or imaginative idea of what being a monk might be like. Also, study and practice in a variety of disciplines was helpful because it gave me a bigger picture of the world, which helped me to understand the study of Buddhism from different points of view. It maybe gave me ways to communicate to different types of people, too. So, like that, a little study and experience of ordinary life has been useful in making my ordained life more robust. As far as helping my study here, well, the more points of view and experience you have will always help any future study, right? A broader view helps make sure you don’t have blinders on, that you can see how different things might fit together.

You were ordained when you were twenty-five, shortly after finishing university. So in a very short time span you went from knowing nothing about Buddhism to ordaining as a monk. How did that come about?

I was actually twenty-two when I went to that first conference and twenty-three when I went to Maitreya Instituut for the first time in 1993. Having received my first teachings at Maitreya Instituut, within a few months I already thought, “OK, I have to become a monk.” Then Geshe-la very kindly said, “Don’t rush, wait. You finish uni. You stay for at least a year in the center, study more, and then we talk again.”

I graduated and then worked for the government on a project for a while. Then I finished that and lived at the center. I talked again to Geshe-la, and Geshe-la said very kindly, “OK, so if you want to become a monk, what do you want to do? Go and look at India, have a look around, see what you want to do.” So that’s what I did. Eventually I was able to see Lama Zopa Rinpoche again, who I had met him the first time in 1993, and his advice helped me make the final decision.

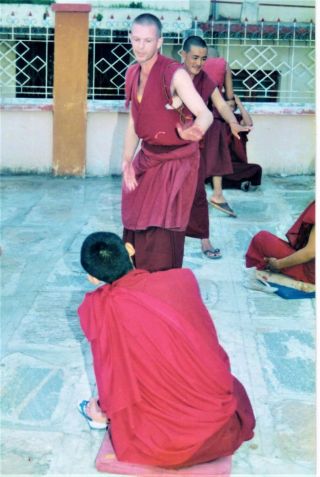

Debate in the courtyard at Sera Je Monastic University, 2009, India. Photo courtesy of Ryan Matsumoto.

In a 2016 Mandala article that you wrote, you say that a lot of Westerners are short-sighted, wanting to focus only on meditation practice or only on study, and they don’t create any sort of unity between the two. When you first ordained, you quickly joined Sera and began an intense study program, so I am wondering, does the advice you give come from personal experience? What led you to join the geshe curriculum at one of the Great Seats [Sera, Ganden, and Drepung] instead of focusing on meditation or retreat?

[Laughs] Well, I was very short-sighted in the beginning, too. I thought, “I will become a monk and there is no need for Tibetan language, I will just do everything in English. I will do retreats.” That’s what I thought. But then my teachers— Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Dagpo Rinpoche—so kindly made it very clear that that was not the right way to go. They emphasized learning Tibetan, and based on that, going to and studying at Sera. Of course, initially, I didn’t know much about the program; it wasn’t on my mind until it was advised. So I started to learn some Tibetan in Dharamsala and then based on Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s advice I came to Sera. So that advice in my article comes from being one of the short-sighted people myself! And it was really the blessings from my gurus to see how not learning Tibetan or studying wasn’t the right way. They helped guide me to where I am now.When you first ordained, if someone had told you that you were going to start a twenty-year study program and earn a geshe degree, what would you have said?

Rinpoche told me in 1993, the first time we met! Of course, at that time it didn’t make sense. Rinpoche told me, “Learn Tibetan; become a geshe.” At that time I didn’t even know what a geshe was all about, so it was quite strange. But the idea of being in a study program for twenty more years, and finishing that and getting the geshe degree? Of course, that never comes to mind. You never think that far ahead, generally speaking. The gurus have this long-term view, but most of the time that is lacking for us. Initially I thought, “Learn Tibetan, study a bit, see how it goes. Maybe do the Prajñaparamita studies and the Madhyamaka studies, but then leave and do retreat.” But later Rinpoche told me very clearly to keep going.

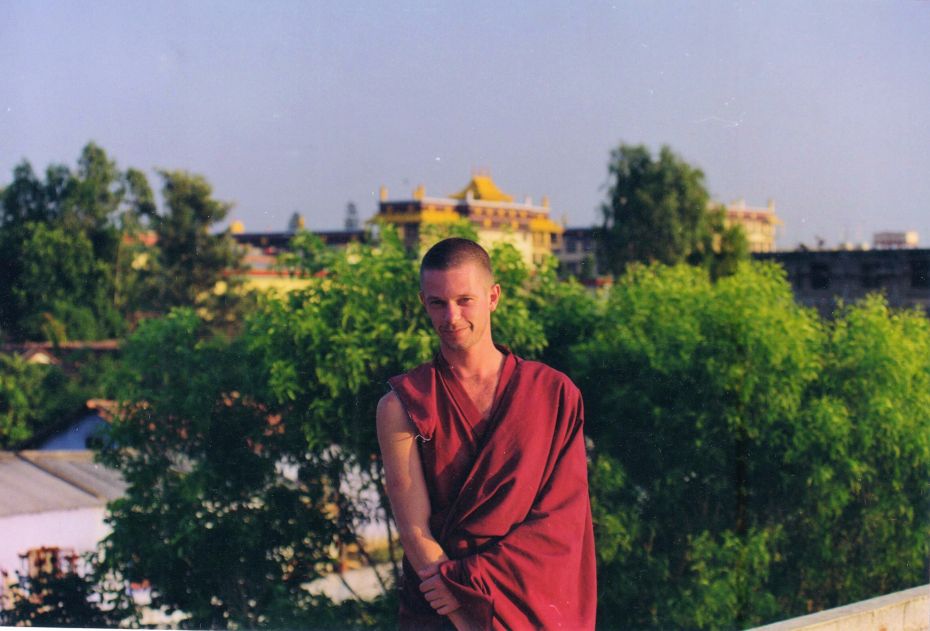

Ven. Namdak in his early days at Sera Je monastic university. Photo courtesy of Ven. Namdak.

When you finally joined the geshe program at Sera you were one of very few Westerners here, and living at the monastery was more difficult then. In addition, over any course of study or practice internal difficulties are bound to arise as well. How have you navigated those difficulties over time?

It’s true, Sera was very different than it is now. The conditions were much rougher. For example, I lived in the khangtsen and there were no showers, only a bucket for washing outside with the hand pump. The toilets were horrific. The food wasn’t as good as it is now. I lived with a roommate in a very small room, and it was always noisy and without privacy. It wasn’t always clean.

Initially, it was pretty rough. In one aspect, it was difficult. But the other aspect is that it was very good for practice. The Tibetans, they do a lot of teasing, you know? They try to go as far as possible to make the “I” come up before you actually get angry. And that is not always easy! But, in the context of the study program, it was a very helpful way to practice. Of course, sometimes I would get a little fed up. I would go to a friend’s place at the other side of the monastery and would stay there for a few days!

Even if you have good outer conditions, sometimes you can have some mental obstacles and your mind gets unhappy. Those kinds of experiences can happen wherever you go, whatever you do. But, especially here at the monastery, if you were to leave, what else would you do? Seeing the incredible benefits of the system, what else would you do? Sometimes I thought maybe retreat would be better, but other than that, nothing else came to mind. The mind maybe is unhappy, maybe because the outer conditions are difficult or maybe some other reason, but the truth is that unhappiness never comes from the outside and there really is no other place to go that offers the same benefits. The gurus advise us to stay here because no matter where you go, you cannot run away from your unhappiness—you bring it with you. You can only run away from a very beneficial opportunity for study and practice! My strategies are always the same: I try to step back to take a longer view, trust in my guru’s advice, and rejoice in the many benefits that I have. Difficulties may come, they may even stay for some time, but at a certain point, they disappear.

You have seen a lot of changes to the monastery and its academic program over the last two decades, and even more if you consider what we know of Sera in Lhasa in the early twentieth century. Our enrollment numbers are down every year, the outside world is definitely more distracting than ever before; it seems obstacles come from all sides. Speaking as someone who has now completed this method of institutional study, where does this traditional monastic university go in the future?

Ven. Namdak debating at Sera Je in 2001. Photo courtesy of Ven. Namdak.

According to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the real preservation of the Dharma of the Nalanda tradition is done mainly through Ganden, Drepung, and Sera—the Great Seats. Of course, there are big monastic institutions of the Nyingma and other traditions as well. If those disappear or degenerate, then upholding the whole Buddhist doctrine and the Nalanda tradition becomes more difficult. Sometimes it is important to remember the real purpose of a monastery like Sera: to provide an unbroken and authentic lineage of the teachings of Je Tsongkhapa for all future generations. The heart of the monastery is to do that, and for those of us here, we just get some benefit from being part of that, being close to that. I’m not saying that I am doing that, of course! I just happened to stay here long enough that they gave me this new title.

They say that compared to what it was like in Tibet, the number of really top scholars and the level of scholarship is maybe not so high now. However, the overall level of study is much higher than it was in Tibet, because there is more availability. So even if the top of the top isn’t as high as before, the average is higher, and from that point of view, it is a positive. From another point of view, of course, there are fewer monks coming—and that’s a bit of a worry.

I think that if the monastery can show the monks how to embrace the modern world and modern learning without sacrificing the authenticity of the lineage, then it might help with our enrollment and dropout rates. One way the monastery is trying is the new science studies the monastery has started. His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been pushing science studies forward for the last few decades. Using outside forms of authority—for example, academia—to explore and reinforce the Dharma brings more support and respect from international spiritual and scientific communities, and that is helpful. This is something I have been interested in, too. Not the physical sciences so much, but the mind sciences and some quantum sciences, what bits I can understand. I think they complement the Dharma study and give more tools to use when I contemplate the meaning of the texts. Of course, this kind of study is secondary next to the philosophic studies. It is a yan lag, a “branch.” The main thing is the studies. But if you have science, it is yan lag phun sum ‘tshogs pa, which means the right aspects are present to preserve the Dharma as it interacts with the outer world. The monks need to have an understanding of how to communicate with people outside the monastery, and not just the language, but also the ideas, the concepts. They need a little scientific understanding of the world as well.

For the last twenty years not only have you been engaging in studies full time, but you work for the monastery quite a lot and the greater Dharma community in the area. You helped establish IMI House and have been its director for quite a long time. You helped organize and teach translation courses here at the monastery. You have translated for various lamas that have traveled through the monastery. You’ve worked with His Holiness’s office to run the pre-ordination course in Dharamsala for the last six years. And of course you have been instrumental in the growth of Choe Khor Sum Ling, the FPMT center in Bangalore. The monastery is already a full-time commitment and you add a few more full-time commitments on top of it!

Ven. Namdak with the participants in the pre-ordination course along with Geshe Tsering Choephel and SPC Ven. Kunphen, on Lama Yeshe’s stupa, 2014. Dharamasala, India, 2014.

Well, the monastery curriculum by itself is very busy. On top of that, since I came to Sera, Lama Zopa Rinpoche has always very kindly had something for me to do, in case I were to get bored. In one way, it is a busy schedule, but it gives me satisfaction. If studies are mainly to cultivate and benefit my own mind, then doing these projects for others on the side gives me a little bit of satisfaction, because I can think, “Wow, it’s pretty beneficial to be here because I am doing these studies, but alongside these studies I can try to benefit others as well.” So I think that maybe asking me to do all of these kinds of projects is the kindness of Lama Zopa Rinpoche, to make sure I get some kind of merit! Perhaps a little bit of merit helped me to get through the studies. He always takes the long view, as I said.

Most of the work we do in the monastery is not ordinary work, right? Especially organizing teachings or doing Rinpoche’s projects, like those for the Bangalore center. It is for the vast vision of the gurus, so it is basically also an accumulation of merit. That’s what we like to do in our daily practice as well. We like to accumulate merit and purify negativities and transform the mind. You get a lot of opportunities from following the guru’s advice and all of these other things as well. For example, we had just finished building IMI House here at Sera when Lama Zopa Rinpoche came—that same year—to start the Bangalore center, Choe Khor Sum Ling, on the advice of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. I was very afraid because I thought, “Rinpoche is going to ask me a favor,” and then, of course, Rinpoche did! He is very kind that way. You see how I was thinking only about myself and he helped me break through that? At first it was very tough, there were various obstacles, but that happens with new centers. In the beginning we had to put a lot of effort into it. But then after some time, it started to take off, and we didn’t have to do quite as much work as we did the first few years. Getting to be part of the guru’s vision, seeing something develop like a center, a community that is self-sufficient, and sharing the Dharma—that’s a good feeling. It makes all the work worth it!

Geshe Namdak with students of Choe Khor Sum Ling, Bangalore, India. Photo from CKSL via FB.

Of course, it isn’t always easy to balance these projects with my studies and practice. Sometimes it’s difficult. At those times I just do my commitments and that’s it—there’s no more time. But there are other periods where it is a little more relaxed, you know? I think it’s important, whether or not you’re in the middle of a Dharma project, to make sure to reserve some time for your practice. Take some time off to do some retreat. Or, on a daily basis, don’t answer phone calls until a particular time in the morning, but instead, do lamrim contemplations and commitments quietly and think about the meaning a little bit. Of course, if things have to happen and you have to work, then you have to do the best you can. Dharma projects and center work are also practice, so I always keep that in mind. I mean, we always pray to become a buddha for the benefit of all sentient beings. This is how to do that, you see? Following the guru’s vast vision means that you’re not only doing your own thing and your own practice, but also on the side you are able to benefit others. My personal capacities to benefit others are very limited, of course! Still, I try to follow the guru’s advice, the guru’s instructions, and slowly things work out, no matter how busy things seem to be.

Ven. Namdak receiving a blessing from Lama Zopa Rinpoche at Choe Khor Sum Ling, Bangalore, India, 2016. Photo courtesy of Choe Khor Sum Ling.

You’ve joked about not having any karma with the United States, no karma to live in a big, fast-paced city. Joking aside, what do you think about living as a Dharma practitioner in an environment where the conditions are not considered conducive?

It’s the same in Sera, right? It’s not always easy, whether the conditions are rough or if you have been given advice that keeps you very busy. I think having faith in the long-term vision gives you strength and helps keep the mind happy. When the mind is happy, it is easier to do your practice as well. I always remind myself how far-reaching the guru’s vision is, how the guru is thinking about so much more than just this small moment, and understanding that makes the difficulties of the immediate moment fall away.

I think we are very short-sighted, generally speaking. If you have the long-term view, like the gurus have … I mean, they are looking at lifetimes! But even in one lifetime the mind can change! One year, two years, three years, ten years, it can happen! What the teachers here advise is go over the texts, study, try to put things into practice. It is not always easy and maybe the mind doesn’t change right away. However, all of the seeds are there, the seeds are planted—one day in the future the mind will change. I make sure that, on a daily basis, I am grounded in my practice, grounded in the lamrim and lojong. It is about habituation. Over time it will bear fruit and it will be easier to deal with the external environment and all sorts of people.

You have to have a great vision but without too many expectations—“I’m going to change my mind within a few years” or “I’m going to get realizations if I do this three-year retreat”—because of course it’s not going to happen the way you expect. If we think of the three countless great eons it takes to become a buddha according to the fastest track in sutra system, then what is a few decades of study or a few decades of retreat or a few decades of serving the center, or whatever? It’s peanuts, right? So if you think in that way, about the big picture, how over lifetimes you are going in the same direction, then one day, the realizations come. And maybe before those realizations, even if the situation is rough, you can still find it meaningful and find ways to have it encourage your practice.

Other than the actual Buddhist philosophy, what have you learned the most over the last twenty years here at Sera?

I don’t know. I mean, to develop the mind takes a long time, right? It’s the same with learning a language, it takes a long time. And you don’t really notice if you progress or not because it is a very slow process. I have learned a lot from the Tibetans: to be more relaxed, to do things in a relaxed manner. Some of the monks are very relaxed, but at the same time they work very hard. Keep the mind in that relaxed state—that’s what the gurus show us all of the time. I learned quite a bit from the Tibetans to be serious, to work as hard as you can—but keep a kind of relaxed state of mind. Sometimes that’s not always easy, though!

The other monks at Sera IMI House call you “the MVD,” which stands for the Most Venerable Director, a play on the idea of MVP, the Most Valuable Player on a sports team. And it’s true that you’re a role model and example for a lot of other monks here, Westerners and Himalayan. Is that something you think about?

It is the same way I think about giving talks and interviews. Just generate a good motivation, pray to the guru, and then try to do the best you can do. If it works out well, then, it works out. I don’t really go for thinking about these things too much; it really isn’t helpful to ever think about yourself like that.

Geshe Namdak attending his graduation ceremony with other IMI monks and his students. Sera Je Monastic University, India, May 2017. Photo from Choe Khor Sum Ling via Facebook.

Considering all of your training and your experience, and that you are the first Westerner to enter and complete the geshe curriculum in its entirety at Sera Je, what comes next?

I want to disappear into a cave! Rinpoche advised maybe half teaching and half retreat, and he also indicated to visit different centers, which fits me and gives me more freedom to do some other projects as well. So, I think I will give some courses here and there, do some retreat, as Rinpoche has advised, go to Gyume Tantric Monastery for a year or maybe a little longer. We will see.

So, the million-dollar question, I suppose: Looking back over the last two decades at Sera Je, are you happy?

Happy? At which level? [Laughs] I mean, generally speaking, of course. Finishing the whole study program gives an opportunity to rejoice. I didn’t do much but at least there was some Dharma activity involved for the last twenty years, so that is something to rejoice in, and that makes the mind happy. Having had the opportunity to have studied the five major topics of Buddhist philosophy extensively together with doing countless prayers and pujas in big gatherings of Sangha and having received many precious and rare teachings over all those years feels very fortunate. So, yeah, I suppose I have been pretty happy with how it has gone the last twenty years. I have been very fortunate that the guru gave me this opportunity!

Geshe Tenzin Namdak answering debate questions during the geshe graduation ceremony, Sera Je Monastic University, India, May 2017. Photo courtesy of Sera Jey Audio Visual Center.

Read more about FPMT-registered teacher Geshe Namdak.

Watch a video of Geshe Namdak’s graduation ceremony.

Mandala is offered as a benefit to supporters of the Friends of FPMT program, which provides funding for the educational, charitable and online work of FPMT.

- Home

- News/Media

- Study & Practice

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates – Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Ways to Offer Support

- Centers

- Affiliates Area

- Teachers

- Projects

- Charitable Projects

- Make a Donation

- Applying for Grants

- News about Projects

- Other Projects within FPMT

- Support International Office

- Projects Photo Galleries

- Give Where Most Needed

- FPMT

- Shop

Translate*

*powered by Google TranslateTranslation of pages on fpmt.org is performed by Google Translate, a third party service which FPMT has no control over. The service provides automated computer translations that are only an approximation of the websites' original content. The translations should not be considered exact and only used as a rough guide.FPMT is unbelievably fortunate that we have many qualified teachers who are not only scholars but are living in practice. If you look, then you can understand how fortunate we are having the opportunity to study. With our Dharma knowledge and practice we can give the light of Dharma to others, in their heart. I think that’s the best service to sentient beings, the best service to the world.