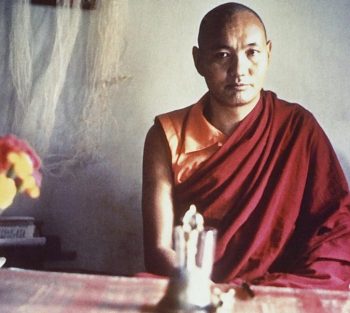

Now, renunciation. The renunciation of samsara is an extremely essential, fundamental thing for all of us. Because if we don’t have renunciation of samsara, what happens is that we totally rely, our attitude is to totally rely, on sense objects, such as this flower, for our pleasure—the relationship pleasure of this flower.

So if we don’t have renunciation of samsara, our attitude contains some kind of deeper trust, preconception idea, that, “I trust you [this flower] completely—you are the source of my happiness therefore I love you, you should love me.” This kind of attitude, unreasonable, overestimating attitude, to temporal phenomena is too extreme. Such grasping attitude toward temporal pleasures, unreasonable, overestimating attitude is painful; its nature is painful.

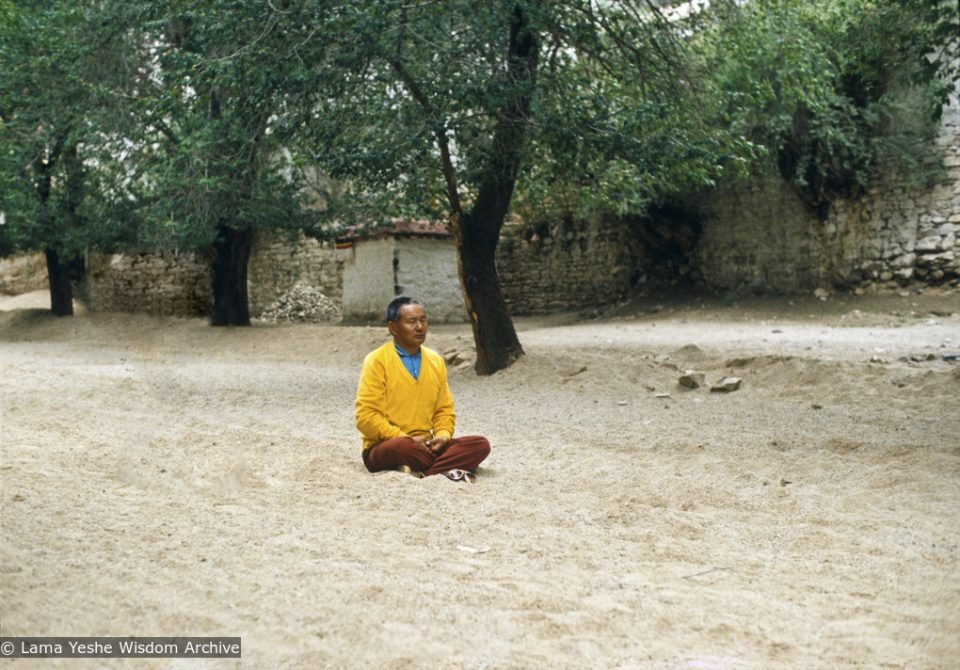

So we should have strong impression, impression to convince ourselves, “Yes, this is good at the moment; OK, it helps something, it gives some pleasure, temporal pleasure. OK, I accept that. But I should not expect more than that.” So there is less tension in this relationship. Just as this example, for the whole existent phenomena, all Australian pleasure is the same thing—transitory, no solidity. We should accept when this disappears, without any miserable reaction. Who cares? This is time to disappear, disappear. So that all the pleasure, what we consider as sense world, disappear, disappear; come, come. The thing is that renunciation of samsara makes you flexible; at least flexible.

There’s no strong reaction: this disappears, my heart shakes. Why? The nature of this is to disappear. My nature is to disappear, so what? We have to accept, without uptight and fear or tension, and without holding such unrealistic ideas on the reality of any existent pleasure or pain.

Buddhism teaches your mind to act in the middle path, by avoiding extreme views. If I make an example, in Australia, boys worry about their girlfriend and girls worry about their boyfriend—losing these things. That’s the samsaric mind, not having renunciation of samsara. Instead of crying day, day, and night, night, better meditate on renunciation of samsara! Well, that’s why Buddhist philosophy is so simple, so practical—it deals directly with everyday life. Philosophy is not some kind of ancient history—it’s the philosophy of the scientific reality involving what is happy and what is not happy.

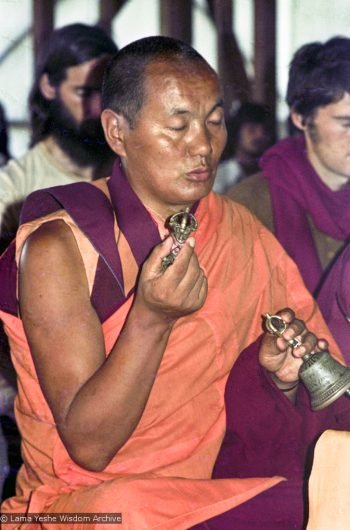

Now, bodhicitta is understanding that all universal living beings have the problem of attachment and the symptoms of ego and feeling sympathetic; more universal levels sympathetic rather than only the small view of oneself, extreme sensitivity looking me, only seeing me. Me is the most horrible, I am, look at all that. From the point of view of the great vehicle, Mahayana, that is still a neurotic attitude even though it has some good quality. It’s true—when we look more at the world, how sentient beings are suffering, your pain is nothing, your pain becomes almost nothing, so that psychologically you have room, there is room.

Besides that, taking responsibility, that it’s possible if I can develop myself kind of perfectly, totality, actually I can do, I can lead all these sentient beings into perfection, or liberation, or enlightenment. It’s possible. And feeling that I can take the responsibility myself; it’s possible seeing also the potential.

When we think about it, we might say, “Oh, that is just a joke; that is just a Mahayana joke, Buddhist joke. There are too many insects, mosquitoes; so many sentient beings. And how many days are there in one year, in my life, how many days?” We make these things up, we make time up. Time—day and night—is our interpretation. These things are not self-existent. We have such incredible idea that time is very short and Buddhism says things that way how can I possibly do it.

We kind of suffocate ourselves, “Oh Buddhism has such incredible ideas—the ideas put me like this. [Lama demonstrates being suffocated] I am here, therefore I can’t.” Then the question is that your measurement of life and time, and day and night, months and year is nothing; you have just made it up, human beings make it up, make pressure.

In other words, who made it? First of all the nineteenth century, what we made is when it starts, so human beings made it up, decided from time of Jesus, blah, blah, blah, and these centuries, dah, dah, dah, dah, and before that … we do that one and everybody announces A.D. That’s all isn’t it.

So we believe, “Oh, A.D., yes, day, night, June, July, August, September.” And we make incredible packet like this—June here, July here; kind of difficult, so difficult. In reality, all these things have been made up by the garbage mind, to become garbage. So we are in difficulty.

The bodhicitta attitude is, as I mentioned, taking responsibility for all universal sentient beings. For countless lives because of attachment, the neurotic ego, they have been made to suffer. Actually, this is not absolutely existent within me, nor in them either. The release of this bondage, extinguishing this bondage, is liberation.

So compassion starts that way, compassion. Even though the bondage of ego and attachment are not the absolute nature of beings, the strong wind and many big waves come and cause turbulence. Therefore, it’s possible. The word “bodhicitta” is Sanskrit—it is, literally, an opened heart. The opened heart is bodhicitta.