- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

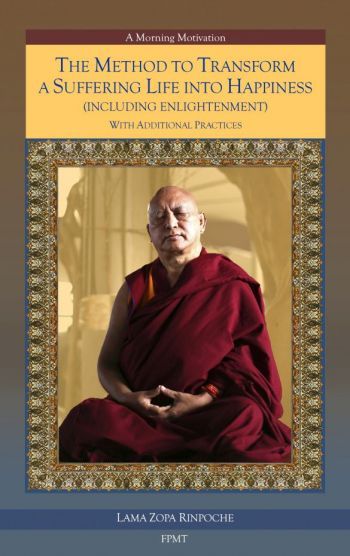

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

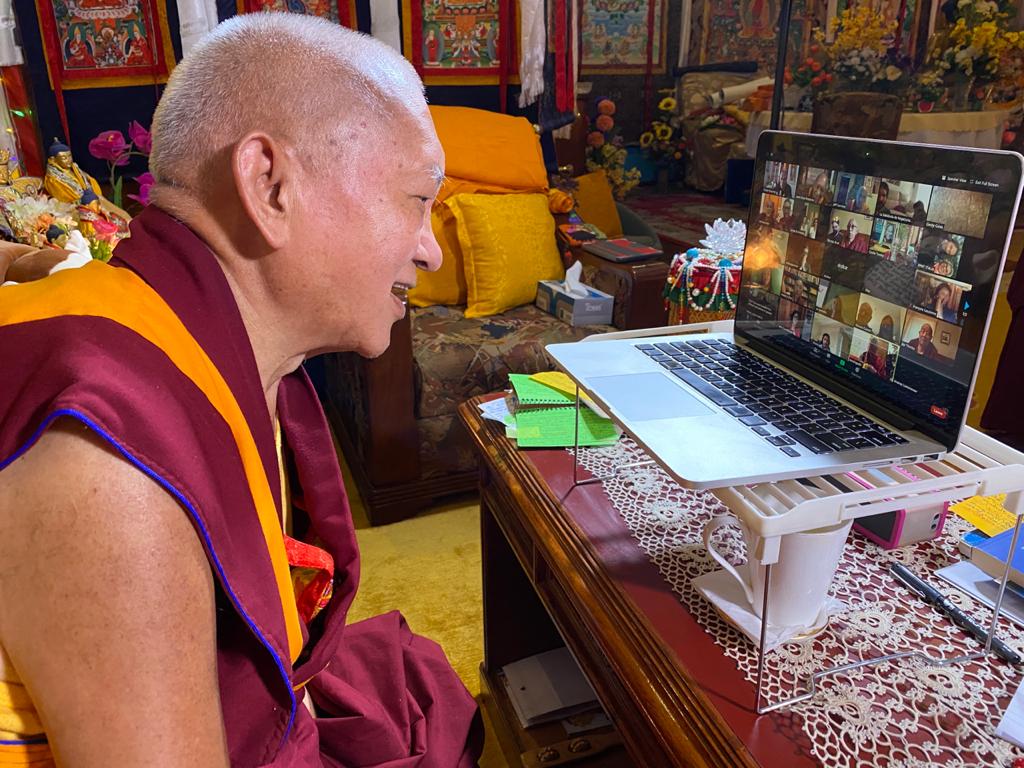

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

Don’t think of Buddhism as some kind of narrow, closed-minded belief system. It isn’t. Buddhist doctrine is not a historical fabrication derived through imagination and mental speculation, but an accurate psychological explanation of the actual nature of the mind.

Lama Thubten Yeshe

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

Obituaries

13

Sara Ritter during the 2012 Maitripa Spring Celebration. Photo courtesy of Maitripa College.

Sara Ritter passed away at the age of 51 on February 6, 2025, from complications from pneumonia.

By Carina Rumrill

As the person who puts together obituaries for fpmt.org and our community news blog, there are inevitably times when I have to organize life remembrances for those I also consider very dear heart friends. Sara Ritter was undoubtedly such a friend.

In 2008, when Sara was publisher of Mandala magazine and one of the editors, she hired me as the new managing editor. The moment I first heard her voice during a phone interview for the position, I thought: “Oh, it’s you!” I had never met her in this life, but I knew immediately that our connection was deep. We did the interview for maybe fifteen minutes before launching into any and every personal detail about ourselves. It was like catching up with an old friend. We both had small boys close to the exact same age; their last names were oddly similar (Bloom and Blumenthal); and we shared so many similar interests, points of view, aspirations, and concerns about the world. And most importantly—we shared a very unconventional sense of humor! As I would learn, many people had this experience with Sara. She knew how to really connect with others.

Sara Ritter and Carina Rumrill, 2009. Photo courtesy of Mandala magazine.

On my first day at the job, she scurried into my office with the excitement of a pre-teen girl having her first sleepover with a friend. She wasted no time making sure I was entirely at home and comfortable. She took me and then associate editor, Michael Jolliffe, out to lunch and she was just bursting with ideas and energy about the future of the magazine and a potential membership program to help fund it (which eventually turned into the Friends of FPMT program). Sara was always so full of ideas. She was a big, brave thinker. I marveled at how she conducted herself in staff and management meetings, always so open, fair, courteous, and diplomatic.

I found Sara to be laser-sharp, hilarious, kind, open, deeply emotional, humble, and full of surprises. She was always so present during our interactions: she made me feel like I was the only person alive on the planet when we spent time together. When she was no longer working for FPMT International Office, she was always just a quick trip downstairs at Maitripa College. I continued to run things by her as I found my way managing and publishing the magazine. Her feedback and engagement was always so valuable and thoughtful.

Sara and Tripp Ritter. Photo thanks to Tripp Ritter.

During this time, I was not only working for Mandala and International Office, but I was also a small business owner. Sara supported the upstart of my food truck every single step of the way. She brought her family to eat there regularly and was never shy with constructive feedback or gratuitous praise. She never missed a single community event we organized to support the business and community. She participated in our marketing video when we expanded. She even brought her wedding party and out-of-town family to the truck as part of her post-wedding festivities! She used every opportunity to support others; this was such a central quality of hers.

Sara Ritter presenting her final MFA work, 2024. Photo courtesy of Tripp Ritter.

She and her husband, Tripp, and their four kids eventually moved from Portland to Seattle several years ago, and shortly after, I moved with my family to Vermont. We kept in touch through social media, with occasional longer messages updating each other about our busy and complicated lives. Sara had recently completed her Master of Fine Arts in Poetry at Pacific University. Sara was, in her heart, always first, a poet. I am so very pleased that she actualized this core aspect of her identity before she passed.

Her husband, Tripp, opened his obituary for her in the following way:

“The poet Sara Kristen Ritter passed away at the age of 51 ….” The poet Sara. That she was.

Tripp also shared:

“One of her greatest professional and spiritual accomplishments was playing a key role in organizing the three-day environmental summit with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in conversation with spiritual, environmental, and political leaders in the Pacific Northwest hosted by Maitripa College in Portland, Oregon. When she cared about something she gave it her all and ensuring His Holiness had a fulfilling and impactful visit was incredibly important to her. Fortunately, the event was a resounding success.

Sara Ritter greeting His Holiness the Dalai Lama during the environmental summit hosted by Maitripa College, 2013. Photo courtesy of Maitripa College.

“In her professional work and in her personal life, what stands out about Sara is the care she gave to others. So many shared that when she was talking to them, it was like no one else existed. She loved life and love and wanted others to find their own joy. Among her favorite things were being a mom and step-mom, a wife, playing games, listening to music, working together on a crossword, watching a cooking show, and visiting the Oregon and Washington coasts.”

Sara and Tripp Ritter with their children. Photo courtesy of Tripp Ritter.

On February 7, a guru puja was organized for Sara at Maitripa College. Over forty participants joined online and in person. During the puja, Yangsi Rinpoche, President of Maitripa College, said this about Sara:

“Most of us here have a connection with Sara. Particularly myself—at the beginning, when I first came to Portland, Sara was my host. And then she was involved in the establishment of Maitripa very intensely. She played a very important role in student services. She was a really wonderful person and a sincere practitioner, and she served all of us. Sara is very close to our hearts, very dear to our hearts. Today we make prayers and dedicate for her journey, for her future, and for her to have perfect conditions to meet her spiritual path, the path that leads to benefiting sentient beings. And then also for Ben [her son], who we have known his entire life, who is also a part of our family. And for all of her community and relatives and friends who are going through difficulty now, that this difficulty can be part of a spiritual transformation.”

Sara, her son Ben Blumenthal, Tom Blumenthal, Tiffany Blumenthal Patrella, Jack Blumenthal, Susan Blumenthal, Geshe Tenzin Dorjé, Yangsi Rinpoche – at the dedication and opening of the James A. Blumenthal Library at Maitripa College, October, 2015. Photo courtesy of Maitripa College.

Namdrol Miranda Adams, Dean of Education at Maitripa College, and Leigh Miller, faculty member and Director of the Master of Divinity Degree and Chaplaincy Program recalled this about Sara:

“Since the announcement to the Maitripa College community that Sara had passed, many messages have flooded in with a common, cherished remembrance—that of Sara’s unfaltering kindness towards everyone. Many also recall her heart for service, be it towards students, or teaching meditation to prison inmates, or hosting opportunities for rejoicing in the community and life celebrations of others. As a mother, she glowed with love and pride for her son, and kept his drawings and photos by her desk. She was fun-loving, with an uninhibited laugh, putting others at ease and bringing smiles to all.

Sara during the 2008 winter “prom” at Maitripa College. Photo courtesy of Maitripa College.

“Those of us who worked closely with Sara in the Maitripa College office saw many additional good qualities. While she started here as a student, she soon selflessly put her own coursework aside to facilitate the educational experience of other students, becoming the Director of Student Services. In this role, she was a warm, welcoming presence to all, helping them obtain housing, visas, scholarships, referrals to Buddhist-friendly therapists, and more. She invented and, for several years, brought to fruition the Portland City Sit, a day of meditation for all in Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse Square. And when Maitripa College faced an existentially threatening gap in leadership in 2012, Sara bravely and tirelessly stepped up to tremendous responsibility and management of people, communications, and strategic planning, without complaint or expectation of reward. Following that crisis, she again worked incredibly hard—with tremendous vision, love, and generosity—on the planning committee for the 2013 visit of His Holiness the Dalai Lama to Portland and Maitripa College. She was appointed the staff lead in planning the interfaith event, with spiritual leaders representing Indigenous, Jewish, and Christian communities, as well as incorporating a youth choir, Native drummers, and a flower offering by children to His Holiness. Throughout those endlessly long work days over many months, she kept foremost the benefit to thousands of people, and to Maitripa College, of receiving His Holiness, and even when our bodies were tired, her mind was uplifted and encouraging.

Sara speaking during the 2011 Maitripa College graduation. Photo courtesy of Maitripa College.

“She modeled how to be a bright, caring, professional woman. She skillfully aligned her work responsibilities with our commonly held organizational values and spiritual motivations, achieving not only proficiency and accountability, but also fostering loving care for all in the community. When she departed from employment at Maitripa College, we were saddened but also rejoiced in her new opportunities, marriage, and thereafter, relocation to Seattle. Sara remained a friend, visiting on important College occasions, and staying in touch. She is so lovingly remembered. We are grateful for all the blessings she brought us in touching our lives.”

Louise Light, Maitripa College Graphic Designer and Webmaster, reflected:

“Sara loved a good party—not only working to envision themes and help make the annual celebrations happen, but enjoying them fully. As I recall, the Maitripa College ‘City Sit,’ which brought meditation instruction to downtown Portland, was also a project dear to her heart.

Sara during Maitripa College’s Mad Hatter’s Tea Party Spring Extravaganza, 2009. Photo courtesy of Maitripa College.

“On a personal note, Sara’s presence during my daughter Namdrol’s health crisis over many months in 2011 and 2012, was priceless. Yangsi Rinpoche talks about how she was critical support in the office in Namdrol’s absence, but to me, she also was a personal support. She arranged for community members to pick me up at the airport when I arrived from the East Coast, care for me, and drive me to the hospital, and then, as if by magic, for days, someone would arrive at the hospital to drive me to the house for showers and a change of clothes. Sara also communicated to my larger family and Namdrol’s vast network of global friends by filtering updates Namdrol’s treatment and prognosis through one e-list that she coordinated with me and Rinpoche. I’ll never forget Sara’s kindness that year.”

Former associate editor of Mandala, and alum of Maitripa College, Michael Jolliffe observed:

“When I think about Sara, I remember someone possessing a special blend of curiosity, playfulness, devotion, warmth, gentleness, and groundedness. I appreciated her professionalism and positive attitude while serving in her various roles at the FPMT International Office and Maitripa College. I don’t remember her ever complaining about anyone; in my memory, she was consummately diplomatic at all times.

Sara with Michael Jolliffe, 2009. Photo by Molly Stepanski.

“Sara included me in her life as much as she could, and I deeply appreciated the parties she threw in her Portland homes, invitations to game groups at the Lucky Lab pub, and lively conversation at the Horse Brass with her then-new boyfriend Tripp.

“She changed the trajectory of my professional and spiritual life by actively encouraging me to volunteer for Mandala, which eventually transformed into a happy career with FPMT International Office. I have Sara–and her characteristic thoughtfulness and generosity–to thank for the many wonderful experiences I had while working at International Office. She was a truly special person in my life; I’ll really miss her.”

She is survived by husband Tripp Ritter; child Benjamin Blumenthal; step-children Simon Ritter, Bruce Ritter, and Graham Ritter; sister Amy Winkelman; and mother Sheri Winkelman. She is preceded in death by her father, James Winkelman, and Ben’s father, her ex-husband, James Blumenthal.

Compiled by Carina Rumrill with input and care provided by Tripp Ritter, Namdrol Miranda Adams, Leigh Miller, Louise Light, and Michael Jolliffe.

Please pray that Sara may never ever be reborn in the lower realms, may she be immediately born in a pure land where she can be enlightened or receive a perfect human body, meet the Mahayana teachings and meet a perfectly qualified guru and by only pleasing the guru’s mind, achieve enlightenment as quickly as possible.

More advice from Lama Zopa Rinpoche on death and dying is available, see Death and Dying: Practices and Resources (fpmt.org/death/).

To read more obituaries from the international FPMT mandala, and to find information on submission guidelines, please visit our new Obituaries page (fpmt.org/media/obituaries/).

- Tagged: obituaries, obituary

6

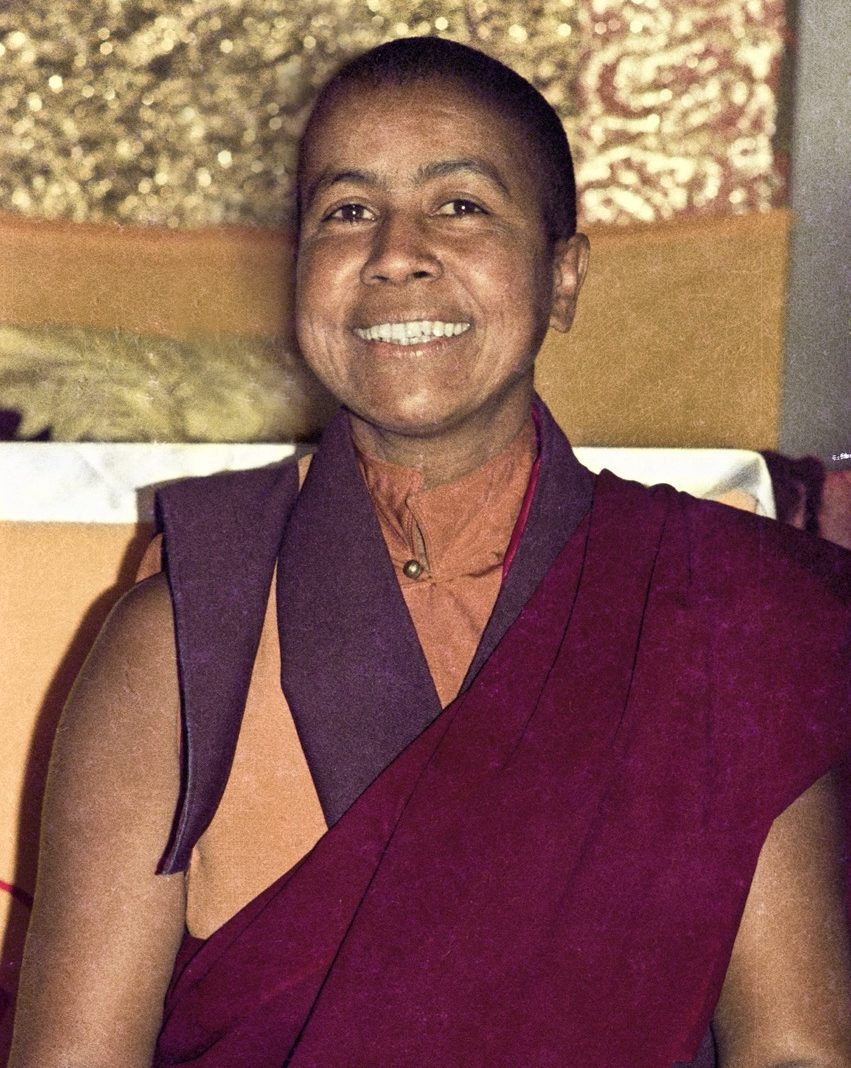

Ven. Ingrid Thubten Nordzin. Photo courtesy Ocean of Compassion Facebook page.

Ven. Ingrid (Thubten Nordzin) passed away after a short period of illness on February 17, 2025 at Tara Home, Soquel, California.

Venerable Ingrid was a beloved and devoted practitioner within the FPMT community for many decades. She received her novice monastic vows in 1988 with Lama Zopa Rinpoche and received full ordination in 1994.

Below longtime friends share some memories, thanks, and wishes for Ven. Ingrid, and tell of the activities being held for her beneficial transition during the 49-day period after her death. We also warmly share below a slideshow by Vajrapani Institute, and an article by Ven. Ingrid, “My First Retreat”, published in the April 1989 issue of Mandala Magazine, with her vivid account of her first meditation retreat in Lawudo, Nepal.

Reflections, Rejoicing and Practices Being Offered

Dear friend to Ven. Ingrid, Thubten Wongmo shares:

“Our dear vajra sister, Ingrid, left this body on February 17 at 4 p.m. I first met her at Kopan before she was a nun, around 1985 and right away we became friends. Since we both have been living in the US, we’ve met at many of Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s courses, both here and in Mexico.

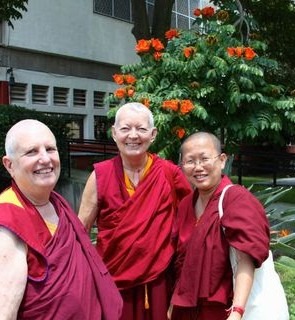

Ven. Wongmo, Ven. Ingrid, and Ven. Tsomo in Mexico, 2014.

“Ingrid was known as the flower lady as she had a talent for creating the most beautiful flower arrangements to place in front of Rinpoche’s throne and on tables next to him. She was very devoted to Rinpoche and would manage to attend as many of his teaching events as possible.

“She had a great sense of humor, and whenever we ended up sitting next to each other, there were lots of laughs. Another talent that most impressed me was her ability to hold pure view. Her closest Dharma friend suddenly stopped all communication with her, thinking that poor Ingrid was the cause of all her problems. This went on for years and even though Ingrid had lost her best friend, she never once criticized her old friend, but insisted that she was Tara incarnate and only acting in such a way as a teaching. Wow wow.

“May our beloved Ingrid be immediately born in a pure land, or be born in a loving Buddhist family, meet the holy Dharma at a young age, find qualified Mahayana gurus, study and practice the path, gain realizations and then benefit many living beings.”

Dear friend, Julie Caldwell remembers:

“In addition to being a nun, Venerable Ingrid was also a teacher. I know this as she was my teacher (along with Lama Zopa Rinpoche) for 22 years. She once told me she had five students. We met in 2001 at The Great Medicine Buddha Retreat and traveled together every year attending Rinpoche’s one month retreat somewhere around the globe. Venerable Nordzin spoke five languages fluently (German, English, French, Spanish, and Greek). In addition to attending Rinpoche’s teachings we would also go to Deer Park in Wisconsin to study with Geshe Lundrub, Sopa.

Ven. Ingrid and Julie Caldwell at Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s house, March 2013. Photo courtesy of Julie Caldwell.

“In addition to flower arrangements, Venerable Ingrid was a great artist. She assisted our study group in Elko, Nevada, in designing and building a Universal Prayer Wheel. It won the National Endowment Award for best Park Landscape design. This adventure resulted in her coming to Elko, Nevada many times over seven years, including helping me transform our home into a pure land so Lama Zopa Rinpoche could visit in 2007, and perform the land blessing. This ritual was also attended by members of the Western Band of Shoshone Native Americans. Ven. Ingrid became close with the tribe’s leaders. She also was the artist who drew the hand mudras published in the Vajrayogini Self-Initiation practice.

“Lama Zopa’s Rinpoche also acknowledged her as my teacher on multiple occasions. Perhaps the most profound was during COVID when I did not travel. So I wrote a question for Rinpoche on paper, “Any advice for my husband’s cancer?” And tuned in at 1 a.m. my time to a Zoom teaching he was giving to the students in Singapore. He looked up and said, “The person with the question about her friend with cancer….you know the nun… follow her advice.” Venerable Ingrid was that nun and was known to heal many people with cancer. My husband followed all of her advice and he also is now cured.”

Ven. Angie Muir, on the practices for Ven. Ingrid’s transition: Ven. Ingrid was at Tara Home for her last three days until she passed, which again would have been very comforting for her since this was her wish to pass away there. Many friends as well as the hospice volunteers offered prayers for her there, as well as Ven. Jangchub, who was doing prayers at her bedside as she passed. Fortunately, Yangsi Rinpoche had been nearby teaching at Vajrapani Institute and came to offer prayers for her the day before she passed. She opened her eyes during the prayers and looked at Rinpoche directly for a moment, very aware he was there. It was surely very moving for her.

Ven. Ingrid, photo courtesy of Thubten Wongmo.

We held a memorial puja for her on Saturday, March 1, at Land of Medicine Buddha. It was attended by around 50 people, in person and online. We chanted the Medicine Buddha Puja and recited the King of Prayers. This was followed by some heartwarming storytelling of her life and qualities by some of her close friends and Dharma family. At the conclusion, we all enjoyed chai and some of the cakes we offered during the puja, two of her favorites, princess cake and blueberry cheesecake. Land of Medicine Buddha also arranged a beautiful assortment of bouquets which she would’ve enjoyed, being a lover of flowers, especially since there were some of the delightful, sweet-scented spring varieties.

There will be a weekly puja for her up until the 49 day period ends, which will be led by various sangha members in the Bay Area of California. The details for the times and days of the pujas are on the Land of Medicine Buddha website.

We were very fortunate to be able to check with Geshe Ngawang Dakpa, long-term resident teacher of Tse Chen Ling, who advised the time and which direction to move the body. He also advised to make a Shakyamuni Buddha statue on her behalf, which has been completed and will be offered on her behalf to His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Together with Medicine Buddha Practice and the King of Prayers, Geshe Dakpa also asks us to recite the Vajra Cutter Sutra as much as possible during the 49 days.

From the International Mahayana Institute Sangha: From the bottom of our hearts we thank Venerable for all the Dharma and good works for others she has done. For all the beautiful offerings she created, the flowers and holy objects. For her devotion to Lama Zopa RInpoche and all her lamas, for being their hands. We rejoice in her wonderful merit and beneficial life.

Vajrapani Institute prepared a slideshow of Ven. Ingrid’s life for her memorial service

Please read “My First Retreat” by Ven. Ingrid Nordzin, published in Mandala magazine, April 1989.

Please pray that Ven. Ingrid may never ever be reborn in the lower realms, may she be immediately born in a pure land where she can be enlightened or to receive a perfect human body, meet the Mahayana teachings and meet a perfectly qualified guru and by only pleasing the guru’s mind, achieve enlightenment as quickly as possible. More advice from Lama Zopa Rinpoche on death and dying is available, see Death and Dying: Practices and Resources (fpmt.org/death/).

To read more obituaries from the international FPMT mandala, and to find information on submission guidelines, please visit our new Obituaries page (fpmt.org/media/obituaries/).

- Tagged: obituaries, obituary

19

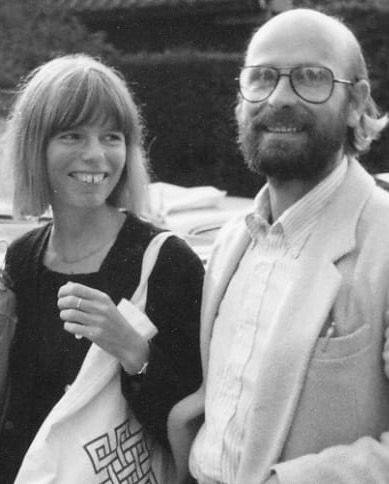

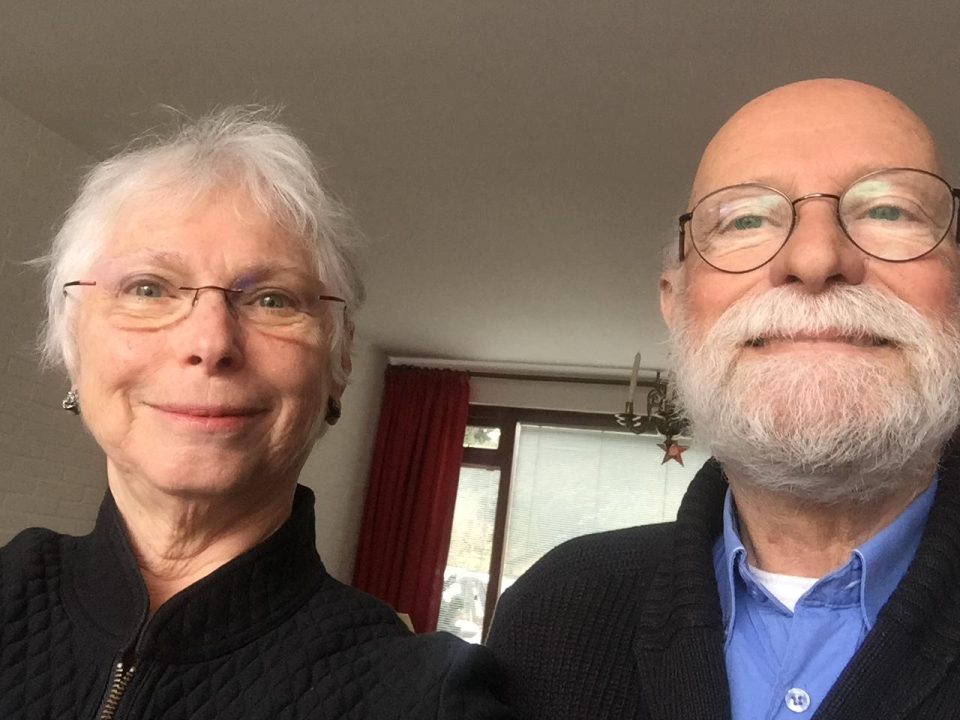

Margot and Jan Paul Kool at Maitreya Instituut, the Netherlands. Photo courtesy of Jan Paul Kool collection.

Jan Paul Kool passed away from cancer on November 29, 2024 in Apeldoorn, the Netherlands, aged 78.

Obituary by Paula de Wys with thanks to Ven. Yangdzom (Koosje vd Kolk)

On December 9, 2024, a memorial service was held at Maitreya Instituut in Loenen, the Netherlands, for Jan Paul Kool, one of the founders and driving forces of Maitreya Instituut. Jan Paul passed away some days before after a long period of illness. During the service, which he had planned himself, several of us recollected his amazing accomplishments and dedication through the years and the men’s choir in which he sang for years brought him a beautiful and moving vocal tribute.

Jan Paul met the Dharma in 1976 at the second lamrim course taught by Marcel Bertels in the Netherlands. A few months after the course, Jan Paul met Margot and it clicked right away between them. Soon after he brought her to one of the lamrim afternoons we organized in the winter to show her off to us and also introduce her to the Dharma—and that clicked too.

The following summer they went to Manjushri Institute in England, where Lama Thubten Yeshe, always our great inspiration, married and blessed them. Their honeymoon took them for months to Nepal and India where they lived in a cave in Rewalsar (Tso Pema) and had lots of adventures. They came back totally inspired.

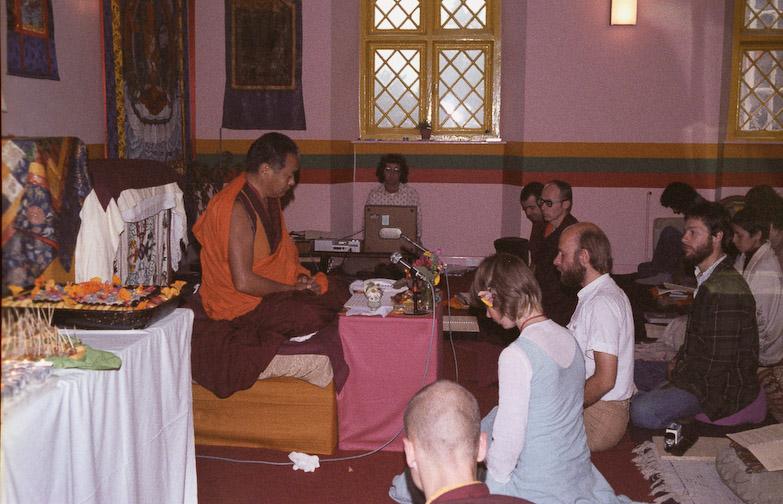

Lama Yeshe marrying Jan Paul and Margot at Manjushri Instituut, photo thanks to Jan Paul Kool collection.

Soon after they returned to the Netherlands, they sailed past my houseboat with a friend and I shouted, “Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa are coming! Will you help?” They were overjoyed. The Lamas’ visit became the beginning of Maitreya Instituut and also Maitreya Magazine, because Lama Yeshe gave us (including Truus Phiipsen) the advice to organize a monthly program and also to publish something in Dutch, so that the Dharma could become accessible to people here in their own language.

Jan Paul and Paula in 2019 at the fortieth anniversary of Maitreya Instituut.

Jan Paul edited Maitreya Magazine for decades and it also became the beginning of the Maitreya Uitgeverij (publishing house). Over the years both Jan Paul and Margot worked with great enthusiasm and skill on translating and editing many books and commentaries of the Lamas, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, resident and visiting teachers, and several other great masters.

Lama Yeshe taking photos of people taking photos at the zoo in Amsterdam, 1980. Photo by Jan-Paul Kool; courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

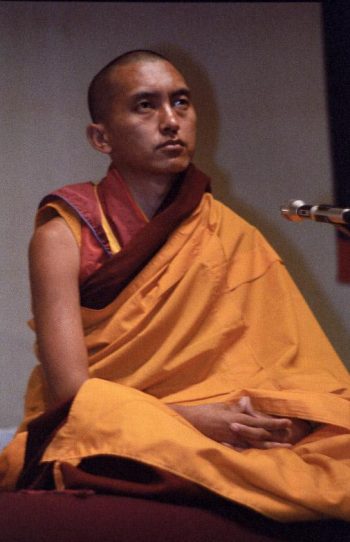

Portrait of Lama Zopa Rinpoche by Jan Paul Kool, 1979.

Meanwhile, Jan Paul had, as a first, invited an amchi (a traditional Tibetan healer) to this country. Ama Lobsang Dolma was a well-known female amchi and came to Europe for the first time to lecture and treat people. The success of that visit was so great that Jan Paul and a few others founded the NSTG (Dutch Foundation for Tibetan Medicine), which then grew into a clinic in Amsterdam and helped over a thousand people in the years that followed.

To talk about Jan Paul and say nothing about his photography would not do him justice. He loved photography and did it very well. The photo collection of his travels, visits of high lamas to Maitreya Instituut and abroad is impressive. Fortunately, several years ago he donated this extensive collection to LYWA where it can remain well preserved and yet useful.

The passing away of his beloved wife Margot in 2012 was a great blow and he missed her until the end. When asked whether he was afraid of dying, he said matter-of-factly, “Not at all, I have the Dharma.” He died very peacefully surrounded by photos of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Lama Yeshe, and Lama Zopa Rinpoche and a mandala given to him by his great friend Andy Weber. The Weber family, Ven. Yangdzom, and some close friends who loved and cared for him in the last months were his Dharma family, and very important to him.

Jan Paul was quite an outspoken character who enjoyed being a pioneer and accomplishing things in his own way. In remembering him it is his truly exceptional energy and devotion to our Lamas that stands out and there is no doubt that he is someone who will be remembered by Maitreya Instituut with great appreciation and gratitude.

Please enjoy a photo gallery of Jan Paul and some of his incredible photography, thanks to the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Please pray that Jan Paul may never ever be reborn in the lower realms, may he be immediately born in a pure land where he can be enlightened or to receive a perfect human body, meet the Mahayana teachings and meet a perfectly qualified guru and by only pleasing the guru’s mind, achieve enlightenment as quickly as possible. More advice from Lama Zopa Rinpoche on death and dying is available, see Death and Dying: Practices and Resources (fpmt.org/death/).

To read more obituaries from the international FPMT mandala, and to find information on submission guidelines, please visit our new Obituaries page (fpmt.org/media/obituaries/).

- Tagged: obituaries, obituary

10

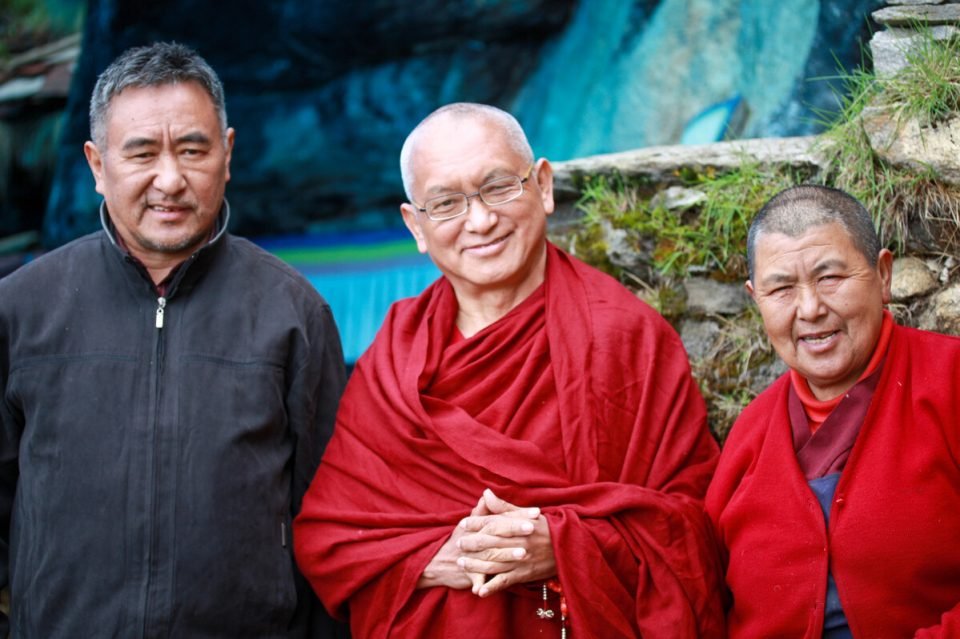

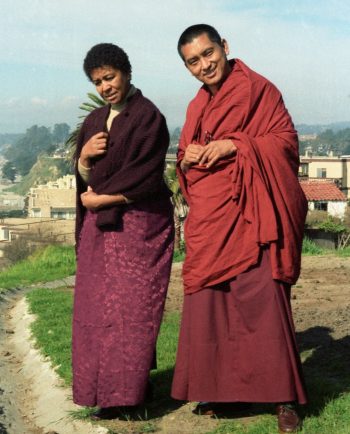

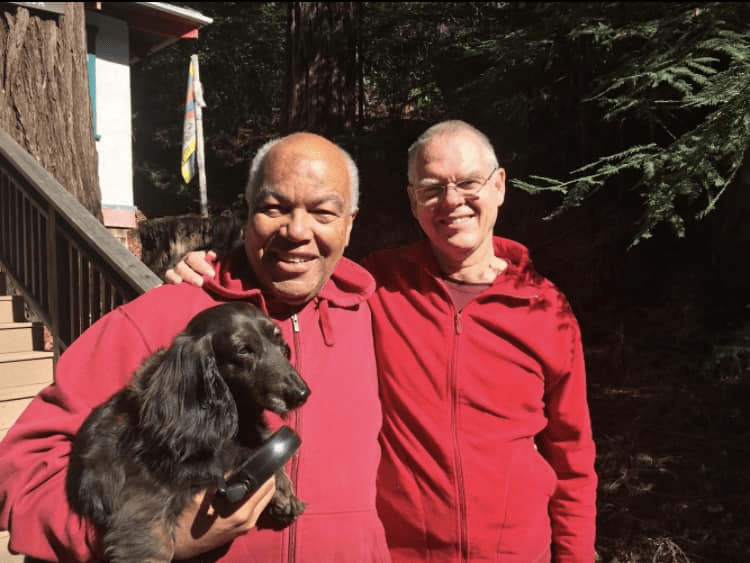

Lama Zopa Rinpoche with brother Sangay Sherpa (left), and sister Ani Samten (right), Lawudo, Nepal, June 2008. Photo by Ven. Thubten Kunsang.

Sangay Sherpa, the brother of Lama Zopa Rinpoche, passed away on December 8, 2024 after an admittance to HAMS hospital in Kathmandu for various health issues. Sangay offered a lifetime of service to Lama Zopa Rinpoche, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and the Lawudo Retreat Center. The cremation will take place on December 11 at Ramadoli Teku in Kathmandu.

In 2022, Frances Howland wrote a moving biography of Sangay, and we invite you to read it now. Please rejoice in Sangay’s beneficial life, recall his kindness, and to also pray for him to never be reborn in the lower realms, to be born in a pure land where he can be enlightened, or to receive a perfect human body, meet the Mahayana teachings, and meet a perfectly qualified guru, and by only pleasing the guru’s mind, to achieve enlightenment as quickly as possible. It is also requested that those who are able to please recite at least one mala of OM MANI PADME HUM and/or The King of Prayers for Sangay at this very important time.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche and his brother Sangay Sherpa and Sangye’s wife, Nyima. March 2021, Kathmanu, Nepal. Photo by Ven. Roger Kunsang.

Rejoicing in the Achievements of Sangay Sherpa

By Frances Howland, written in 2022

Sangay is the younger brother of Kyabje Lama Zopa Rinpoche and his sister Ven. Ngawang Samten. He was born in 1948 in the village of Thame in Solu Khumbu, one month after their father died. They were a poor Sherpa family, and the early years were filled with many hardships due to their father’s untimely death.

In 2008 Lama Zopa Rinpoche requested Sangay to become the director of Lawudo Retreat Centre and for the next 13 years he worked hard raising money and maintaining and developing Lawudo Retreat Centre in accordance with the wishes of Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

The immediate advice from Rinpoche was to tear down the old monastery and build a new, larger gompa that could accommodate 500 monks. Built in 1968 it was in an extremely poor condition and at risk of collapse at any time. The building was sinking into the ground, the front pillars were crooked, and the walls were visibly leaning outwards. However, the senior Lama from Thame monastery, Lama Zopa’s uncle Ashang Yonden, and other Lamas recommended that the old gompa should be preserved as a pilgrimage site because Lama Zopa and Lama Yeshe themselves had supervised and planned the construction and carried some of the stones used in the building. Following this input, Sangay decided to reinforce the foundations with concrete while adding concrete beams and pillars in strategic places, while keeping the original building.

The difficulties of building in the Khumbu region cannot be stressed enough. In 1976 the Khumbu region became the Sagarmatha National Park and was declared a World Heritage Site. Everything must be carried or flown into the area. Even wood used for building cannot be cut from local trees. Sangay had to organize cargo helicopters to carry all the materials he used for all the projects he undertook. This also increased the cost substantially with each helicopter costing around 3,000 US dollars plus the porter charges to carry the goods from the Syangboche airstrip to Lawudo. Despite these challenges, new guest rooms, a new kitchen, major renovations and extensions to the existing buildings plus the construction of a library with a balcony overlooking the valley were all completed. The logistics of all of these projects are mind-boggling.

In late March 2015 a group of us accompanied Rinpoche to Lawudo. Sangay and Ven. Ngawang Samten hosted everyone and there was a big opening ceremony for the new library building, with a procession of monks from a nearby monastery. On April 25th, Lama Zopa Rinpoche had just left Lawudo to return to Kathmandu when a major earthquake measuring 7.6 shook Nepal. No one in Lawudo or the surrounding villages died but most buildings and many stupas on the trails were damaged. At Lawudo the impact was severe. There were cracks in the gompa, the dining room roof fell down, the toilets collapsed, the stone walls of every building cracked open, and the new library where we had just had the opening ceremony was cracked with many stones fallen. Sangay immediately organized an Earthquake Relief for Damage at Lawudo to help fund the repairs.

Another task that Lama Zopa gave his brother was to install a 22 feet-high Padmasambhava statue in the gompa at Lawudo. In the standing aspect of Sampa Lhundrup, it was to face eastwards and be surrounded by seven life sized manifestations, all cast in copper with gold finishing. Sangay commissioned the statues from the skilled Sakya artisans of Patan down in the Kathmandu valley. On 27 June 2016 the statues were helicoptered into Mende, the hamlet closest to Lawudo. Thirty-five Sherpas were needed simply to carry the main statue up the steep mountainside to Lawudo.

In May 2021 a pilgrimage to Lawudo was organized for Lama Zopa and a group of students. Sangay and Ven. Nyima Tashi spent months in Lawudo making sure all the building work was completed and the statues were ready to be consecrated. By then the COVID pandemic was in its second year, and by May the Delta variant was claiming lives in Nepal and India. Once again Nepal went into a total lockdown and the visit to Lawudo was cancelled. Nevertheless Sangay and his team continued undaunted with their extensive program of repairs and upgrades. These included introducing a damp course for the Lawudo cave, building a support wall behind the monastery building, and installing safer steps and walkways for the increasingly elderly Lawudo family.

Another extraordinary achievement from Sangay’s time as Lawudo director was to bring fresh running water to Lawudo and 38 other households in the valley. Anyone who has been to Lawudo will know what an extraordinary feat of engineering would be necessary for such a project. The water is piped at 1.7 litres per second from a height of 4500m through a pipe clamped to the vertical rock faces above. The pipeline was inaugurated in November 2019 and is making an incalculable contribution to the health and well-being of the local population and its livestock. The budget was millions of rupees, much of which was fundraised by Sangay.

Before dedicating his time to Lawudo, Sangay was a successful businessman, and was also involved in the trekking and tourism business. He lives in Chabhil not far from the Boudha stupa with his wife Nyima, his airline pilot son Pemba, and his daughter-in-law Sarita Chhetri and two grandchildren. His other three children are married and live in the UK and US.

Written by Frances Howland, December 2022.

Please pray that Sangay Sherpa may never ever be reborn in the lower realms, may he be immediately born in a pure land where he can be enlightened or to receive a perfect human body, meet the Mahayana teachings and meet a perfectly qualified guru and by only pleasing the guru’s mind, achieve enlightenment as quickly as possible. More advice from Lama Zopa Rinpoche on death and dying is available, see Death and Dying: Practices and Resources (fpmt.org/death/).

To read more obituaries from the international FPMT mandala, and to find information on submission guidelines, please visit our new Obituaries page (fpmt.org/media/obituaries/).

- Tagged: obituaries, obituary, sangye sherpa

25

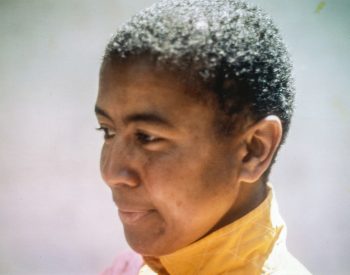

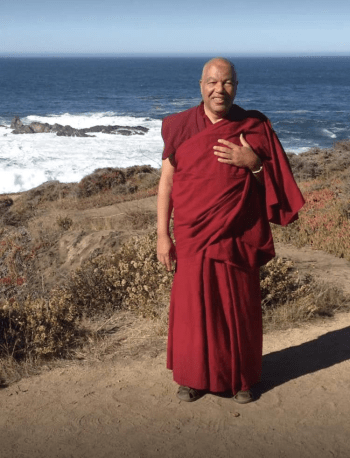

Sister Max giving a talk during the month-long course at Chenrezig Institute, Australia, 1975. Photo courtesy of LYWA collection.

The entire FPMT community shared the loss of one of FPMT’s precious pioneers, when “Mummy” Max Mathews (also known as Sister Max), passed away on February 16, 2024. Mummy Max contributed greatly and financially assisted Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche in establishing Kopan Monastery and the FPMT organization.

Max lived a fascinating life, full of many adventures. Please enjoy this collection of stories, shared from various perspectives, about and from Mummy Max, and rejoice in a full and generous life in service to others, most notably, Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Mummy Max explains in Volume One of Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe: “I felt I had come home and that Lama Yeshe was my guru. He just opened me up completely. I felt balanced and whole, like I was walking on air. I also felt committed. There was no going back.”

“These boys need a mother,” Lama Yeshe told Max [Mathews], when they arrived at Kopan. “You are their Mummy Max.” From Big Love

Chapters

Remembering the Most Amazing Sister Mummy Max | A Very Brief Look at Max’s Many Contributions |

The Car that Saved Mount Everest Centre | Words of Thanks and Reverence for Max Mathews |

The Final Days: A Peaceful Transition

Remembering the Most Amazing Sister Mummy Max

By Peter Kedge, friend of Max’s and another early student and pioneer of FPMT

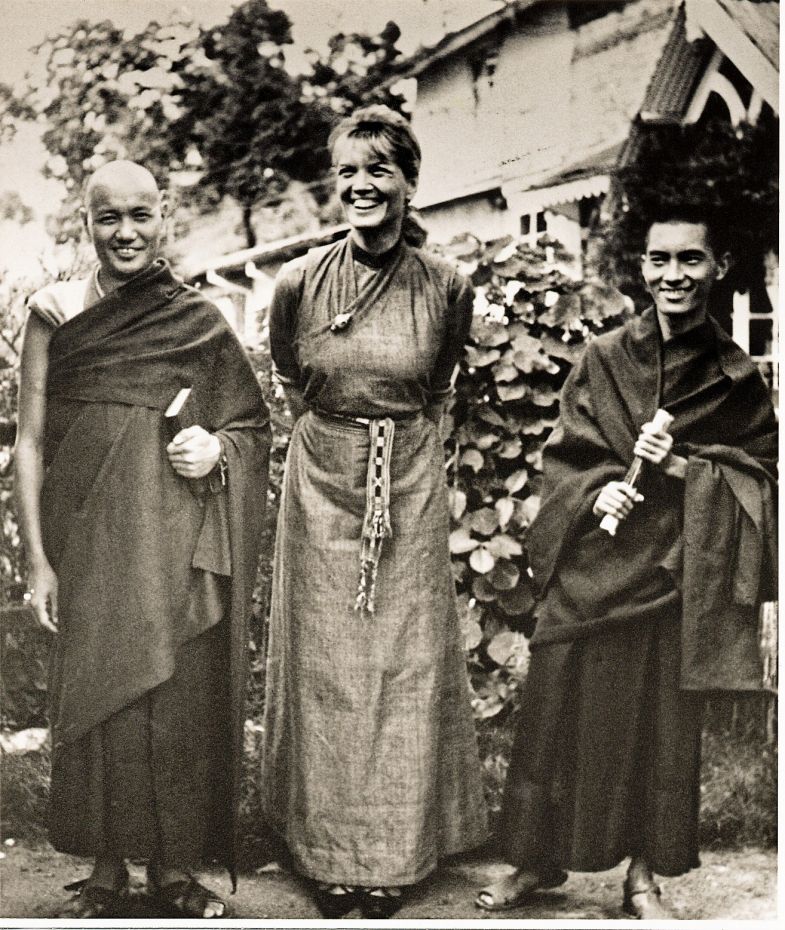

Lama Yeshe, Max Mathews, Peter Kedge, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, First Enlightened Experience, Tushita Meditation Centre, India, 1982. Photo courtesy of LYWA collection.

Born in England, I went to school and University, and in 1966, met up with future FPMT students Harvey Horrocks and Philip Elliott when we worked at the Rolls Royce Aero Engine Division in Derby. We had many adventures together, the highlight of which was probably driving from England to Kathmandu with a plan of eventually reaching Australia.

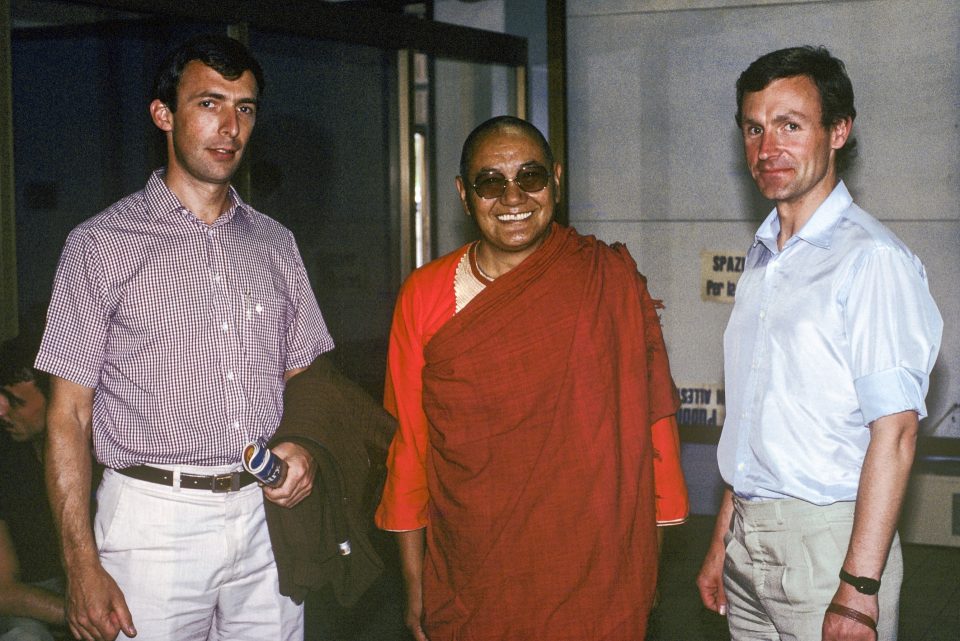

Peter Kedge and Harvey Horrocks with Lama Yeshe at the Pisa airport, Italy, 1983.

Tired of driving, camping on beaches, and exploring the countries we traveled through, we spent six months volunteering with a Christian mission in Pokhara, Western Nepal. We climbed Tent peak in the Annapurna Sanctuary—an experience from which we barely escaped with our lives. We were clearly not mountaineers, and we were clearly not missionary material and so left our hosts to return to Kathmandu.

Harvey and I trekked to Everest Base Camp and another peak, Kala Pattar. On the way we stayed in Namche Bazaar, where I tried meditating for the first time by following instructions from the hippie Bible, Be Here Now by Ram Dass, which one of our female companions was carrying.

On return to Kathmandu days later, I heard there was a Buddhist monastery outside Kathmandu with a Canadian nun, and they were offering a meditation course in English.

Harvey and Philip continued on to Australia. I stayed, and in March 1972, showed up for the second Kopan Course with about 10 others led by Canadian nun Ann McNeil, Canadian monk Jampa Shaneman, and taught by Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Second Kopan Meditation Course, spring of 1972. Included in the photo from the left are Ann McNeil (Anila Ann), Mark Shaneman (Jhampa Zangpo), Steve Malasky, Gen Wangyal, Age Delbanco (Babaji), Peter Kedge, Geshe Thubten Tashi (seated), Losang Nyima. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

During the break times, I heard there was also an American nun associated with Kopan who visited from Kathmandu where she was a teacher at the U.S. International Lincoln School.

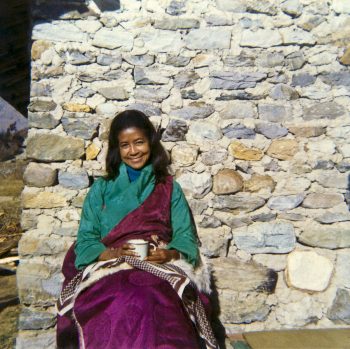

The first trek to Lawudo Retreat Center in Nepal, spring of 1969. Photo courtesy of LYWA collection.

I didn’t see another nun, or at least I didn’t see anyone looking like a nun, until one evening, a black lady in a purple trouser suit drove up and I learned that was Max Mathews the American nun, and the main benefactor of Kopan at that time.

Max heard something about my background, and on introducing herself to me said, “Honey, can you fix cars?” I spent the next three months living in the Rana house Max rented in Tinchuli just outside Boada, and repairing her 1932 Hudson that Max had bought from the King’s palace (see story about Max’s Hudson below).

That was the beginning of 50+ years of close friendship that sadly ended when Max passed earlier this year.

There are two things I remember Max for.

One is the extraordinary karma by which Max’s life brought the foundations of Kopan together.

The other is Max’s unreserved generosity.

Max was born into abject poverty in Redford, Virginia, on October 11, 1933.

After her parents died, social services placed Max with a local family which Max didn’t get on with, so she upped and left for New York to stay with her older sister until social services caught up and placed her with a wealthy family of lawyers in Washington D.C.

Suddenly, Max was circulating in, and learning how to be part of, high society. Later with her Columbia University Master’s degree, government job, diplomatic passport, and postings to Germany, Greece, and Moscow, Max was living life with the elite of the world.

During teaching breaks in Athens, Greece, Max holidayed on the island of Mykonos where she met Ann McNeil (later Anila Ann). Max met Zina Rachevsky (who would become Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s first Western student) in Athens and took Ann to meet Zina. When Max moved on from Athens to Moscow, they each took different paths for the next three years.

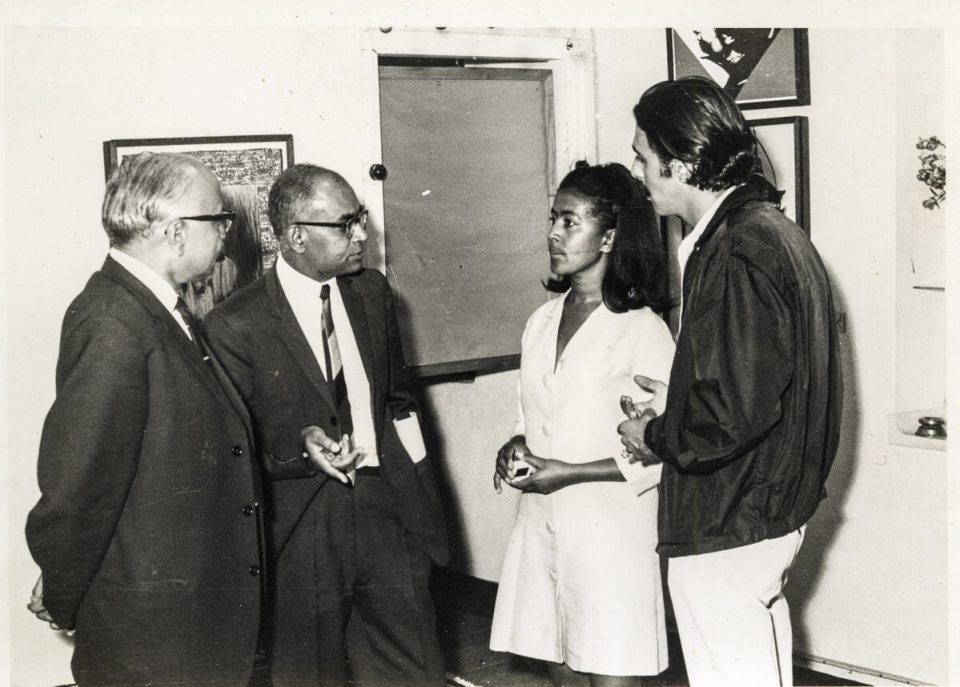

Max Mathews hosting an event at her art gallery in Kathmandu, Nepal, 1969. Photo courtesy of LYWA collection.

Then during Max’s posting to Lincoln School in Kathmandu, Nepal, Zina one day appeared from Darjeeling with Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche. Zina introduced Max to the lamas and on meeting Lama Yeshe, Max collapsed in tears. From then on her life’s purpose was clear.

Zina asked Max to look after the lamas financially because Zina was out of money and Max agreed. Max contacted Ann in Greece and asked her to come to Kathmandu to help her look after the lamas as well.

Lama Yeshe with Anila Ann (Ann McNeil), Kopan Monastery, Nepal, 1974. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

And there they were—Lama Yeshe, Lama Zopa, Zina, Max, and Ann, together in Kathmandu. They were the pioneers establishing the foundation of Kopan and eventually, the entire FPMT organization. Ann, Max, and Zina all took ordination.

For me, the karma that brought that about and all that has followed is nothing short of mind blowing.

The most outstanding quality of Max has always been her unreserved generosity—firstly and foremost toward Lama Yeshe, Lama Zopa, and the Mount Everest Centre (which grew into Kopan Monastery and later, Nunnery as well).

Lama Yeshe on holiday with Max Mathews in Srinagar, Kashmir, 1970. Photo by Domo Geshe Rinpoche who also accompanied them.

Whatever the lamas needed for their well-being and projects, Max did her utmost to fulfill. When Max received her salary check from Lincoln School, she would bring it to Kopan, and give the check to me to take down to Kathmandu and convert it to Nepalese rupees.

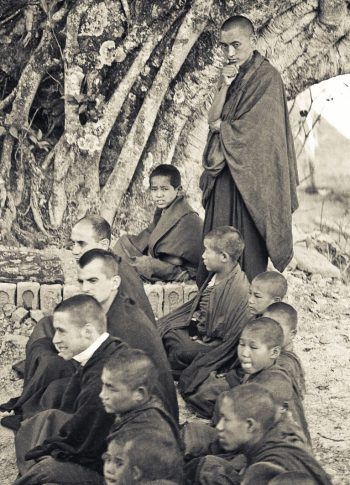

Lama Zopa Rinpoche with Mount Everest Centre boys beside the ancient bodhi tree at Kopan Monastery, Nepal, 1974. Photo by Ursula Bernis.

The rupees would come back up to Kopan and they would be used for whatever Lama Yeshe needed, and now with young Sherpa Mount Everest Centre monks to care for, it meant robes, food, fuel, and accommodations that had to be built as well as a gompa. So Max’s salary also went to buy cement, iron re-bar, sand, bricks, to hire laborers, and pay for trucks to bring all these supplies up to Kopan.

This was Max. Whatever was needed, Max would provide. And not only for the lamas. There was an increasing number of people that Max supported—Tibetans, Nepalese, older monks at Kopan, former monks who had escaped with Lama Yeshe from Tibet, Anila Ann, and other Westerners.

Max became known as, “Mummy Max” as that was the role Max played for so many.

Soon, a teacher’s salary was not enough. Max stopped working at Lincoln School and went headlong into business determined to generate more income.

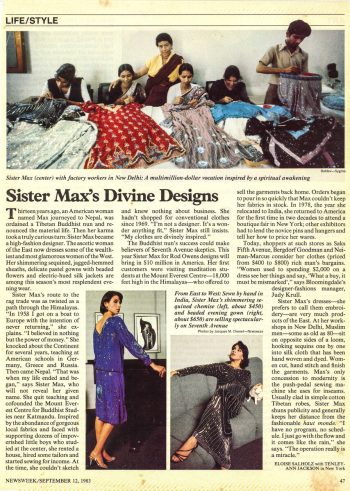

Max started making garments in Kathmandu and then later in Delhi. Max became so successful she was featured in Time magazine with her fabulous line of sequined dresses, which sold for hundreds of dollars in New York.

Max completely supported Lama. When eventually Lama’s health declined, Max paid doctors’ bills and air tickets. Max flew Lama to Delhi, paid for more specialists and hospitals, flew Lama first class to California, paid for Lama’s treatment at Cedar Sinai Hospital, an air ambulance, and all of Lama’s care. Max offered her credit card and made it completely available to cover the considerable expenses of Lama’s funeral at Vajrapani Institute. This was Max’s utter devotion. Lama and Rinpoche always came first.

Max Mathews with fabric for her clothing business, New Delhi, 1976. Photo courtesy of LYWA collection.

The last few months of Lama Yeshe’s life took Max ‘s focus away from the business and unfortunately some of her associates took advantage of Max’s absence during those months and the garment business collapsed.

Even after Lama’s passing, Max was determined to generate funds for Rinpoche, Kopan, and the growing sangha.

Max switched from garments to Indian antique furniture which Max exported to the United States. Max took up residence in Colorado and opened a furniture gallery, traveling back and forth to India to buy stock.

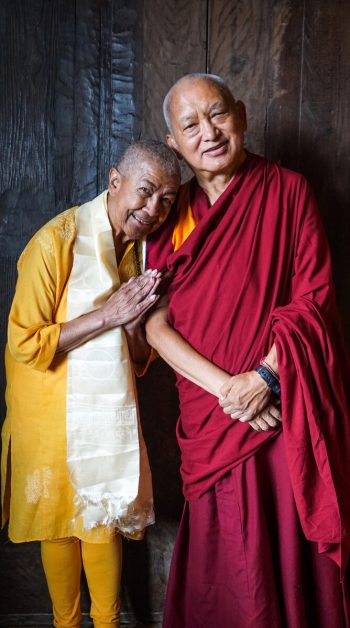

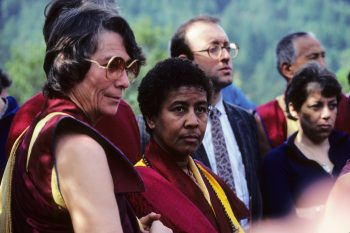

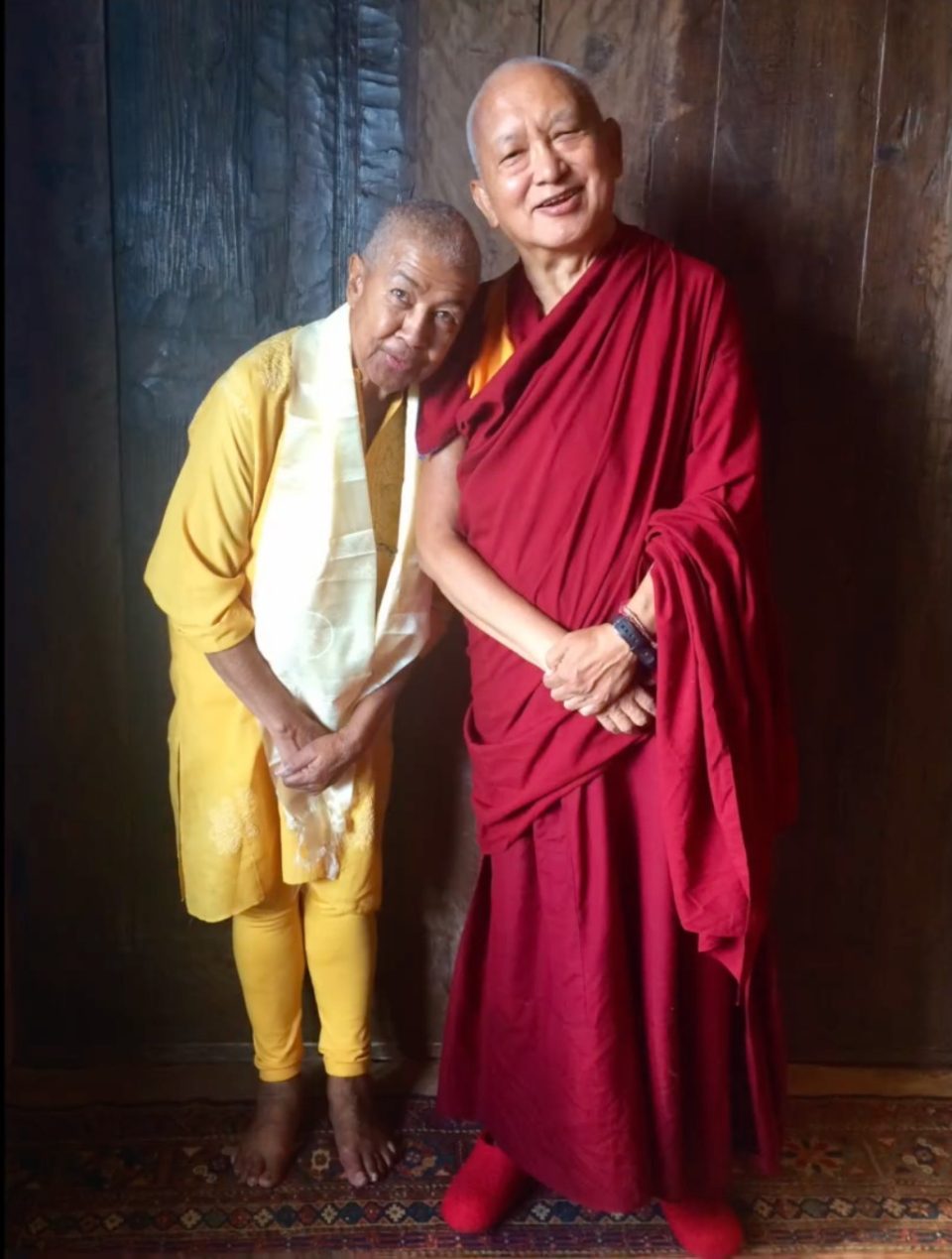

Sister Max and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, United States, August 10, 2017. Photo by Lobsang Sherab.

At almost 80 Max moved into senior housing in Santa Fe and became close with Thubten Norbu Ling, the FPMT center there.

Max never stopped trying to raise money for Rinpoche, the Santa Fe center, and her many other projects. Some of the schemes Max tried were online and unfortunately involved people who took advantage of her trusting nature.

At 88, Max still had a vision of creating, “the most fabulous gallery and restaurant” in the building the center had recently purchased.

Max never sought recognition or thanks. She always downplayed the incredibly significant part she had played in building Kopan, helping Lama and Rinpoche to build FPMT, and as a consequence, helping the spread of Buddha Dharma in the West.

Max’s passing was as close to “textbook” as can be hoped for. Students of the center and visiting geshes kept a prayer vigil. Nursing staff and hospice carers were on hand 24 hours a day and Max passed peacefully at home. The funeral home allowed the body to remain in place packed by dry ice until the consciousness had left.

Of her part in the establishment of Kopan, Max would always say, “I didn’t do anything.” Yet what an incredible life Max packed into her 90 years. What an example of generosity, what an understated contribution Max made to Kopan, and to the life work of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Written by Peter Kedge, friend to Max and early FPMT student, former FPMT Inc. board member, and former director and CEO of the Maitreya Project. Please read this 1995 Mandala magazine article about Peter’s own generous contributions to the early activities of FPMT, “Turning Money into Dharma.”

A Very Brief Look at Max’s Many Contributions

This interview with Max Mathews was filmed in July, 2020 in Santa Fe, New Mexico, with images from Big Love: The Life and Teachings of Lama Yeshe. Mummy Max shares her spontaneous and intimate firsthand stories of her timeless relationship with Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche:

Watch Big Love: An Interview with Max Mathews aka Mummy Max

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQMNDG7-ocE

Adele Hulse writes of Max’s early years in Big Love:

Born in 1933 to a desperately poor black undertaker in Virginia, Max and her siblings had often helped embalm bodies after school. “Embalming was all the go with poor blacks,” she said. Her parents’ marriage broke up when she was around ten years old and she was adopted into a wealthy white family, with a house on the West Coast and an apartment in New York.

Max eventually got a Master’s degree in education from Columbia University in New York, and after graduating she was ready for adventure. Joining the American diplomatic service as a teacher gave her the freedom to travel, the security of American protection and an American salary. Her teaching career took her to Greece, Germany and Moscow. In August 1968, it landed her in Kathmandu.

After receiving her Master’s degree, she was employed by the U.S. Department of Defense, which oversaw the U.S. International Schools network and held postings in Athens, Berlin, Moscow, and Kathmandu since 1958.

In 1960, while working in Greece, Max Mathews met Zina Rachevsky and Ann McNeil, who was originally from Canada. They became good friends. Max spent five years in Greece. She explained, “Of course, we had at least five years in Greece together before the lamas even came, they weren’t even in our knowledge. When we parted, we didn’t know that we had all been students of the lamas before.”

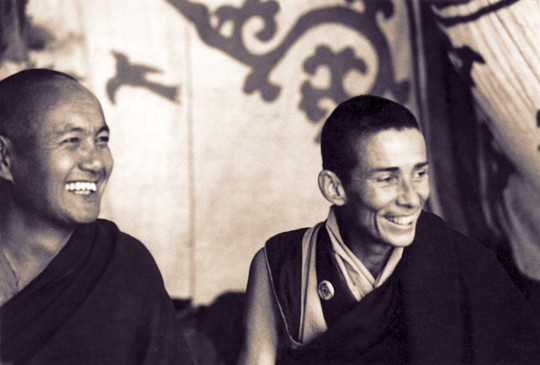

Zina Rachevsky with Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, 1967. Photo via Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

In 1968, Max taught at the U.S. International Lincoln School in Kathmandu. She worked there until the early 1970s. She bought works of persecuted Jewish artists in Moscow and brought them to Kathmandu. In Kathmandu, she would purchase Tibetan thangkas and statues from Tibetan refugees. She opened an art gallery in a two-story building at Kantipath across from the American Embassy Consulate office. The gallery also had a café where poets, artists, and writers would meet.

Max developed good relations with King Mahendra as he was happy about her interest in promoting Nepali art. The King even inaugurated some of her exhibitions.

Lama Yeshe and Sister Max in Berkeley, California, 1974. Photo by Judy Weitzner

In 1968, Zina and Max met again in Kathmandu. By that time Zina had become a student of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, traveled with the lamas, and finally settled in Kathmandu where they decided to build a monastery. Zina came to Max’s gallery where Max and her guests were having a Thanksgiving party and begged her to help take care of the lamas.

Max Mathews and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Aptos, California, March, 1984. Photo by Åge Delbanco.

Max tells about her first meeting with Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche in a 2020 interview:

So, Lama Yeshe was the first one I met, and he opened the door, folded his hands, and bowed to me. And at that time my heart went “Zoom! Open, open, open!” and I was on the floor and in tears. I was crying so hard because whatever he did to me, he put in my heart when he opened it, is still there. And I cried and cried. It was like years, but it was only like five minutes, and Lama Zopa then showed up. And that very moment from the floor, I promised Lama Yeshe because he requested me, and I gave my life, my heart, my body, mind, and soul to him forever, forever. As long as they needed me, I would do whatever I could to help them succeed with their journey. I promised the lamas, when I met them, that I would always be there for them and do and help as much as I could and provide service for them and their journey.

The same year Max visited old friends in Greece and met Marty Widener, who she married in a ceremony led by Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Lama Yeshe in Tinchuli, Bouddha.

Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche finally found a suitable place for building a monastery. It was a house of an astrologer on Kopan hill. With Max’s financial help, they were able to buy the land. Max would spend her weekdays in the city and the weekends on Kopan hill.

The trekking group to Lawudo, pictured from front: Lama Yeshe, Chip Weitzner, Dorje Sherpa, Judy Weitzner. Above: Zina, Max, and behind Max, Lama Zopa Rinpoche. Photo courtesy of Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

In early 1969, Max, Zina, her film crew, Judy and Chip Weitzner, and the lamas left for Lawudo. Max discussed this trip in an interview from 2020:

We spent maybe a week in Namche. Many of the villagers knew Rinpoche. Lama Zopa was the Lawudo Lama. He had been in Tibet studying at the monastery, and people would come running out with kathas and gifts, just because Rinpoche had not come back since he left Lawudo to go to Tibet to study.

Now was the first time. So at this point he must have been early 20s. I’m guessing. I don’t really know, but the people recognized him and were so happy that he was back. And then everywhere we went, the people would come to Rinpoche, and they would request that he would please set up a traditional monastic school for boys. They begged and pleaded with him to open the school. I don’t remember Rinpoche’s response, but I’m sure he agreed, because first Mount Everest Center for Buddhist Studies was opened with 27 boys at Lawudo, which had become Lama Zopa’s cave.

The lamas decided to start Kopan in Lawudo and accepted the first group of young monks. Mummy Max was the main benefactor supporting the early growth of Kopan Monastery north of Bodhanath. “Max’s entire Lincoln School salary supported not only the early building at Kopan, but the entire education and maintenance of about 50 young Sherpa and Tibetan monks in the Mount Everest Centre school,” recalls Peter Kedge.

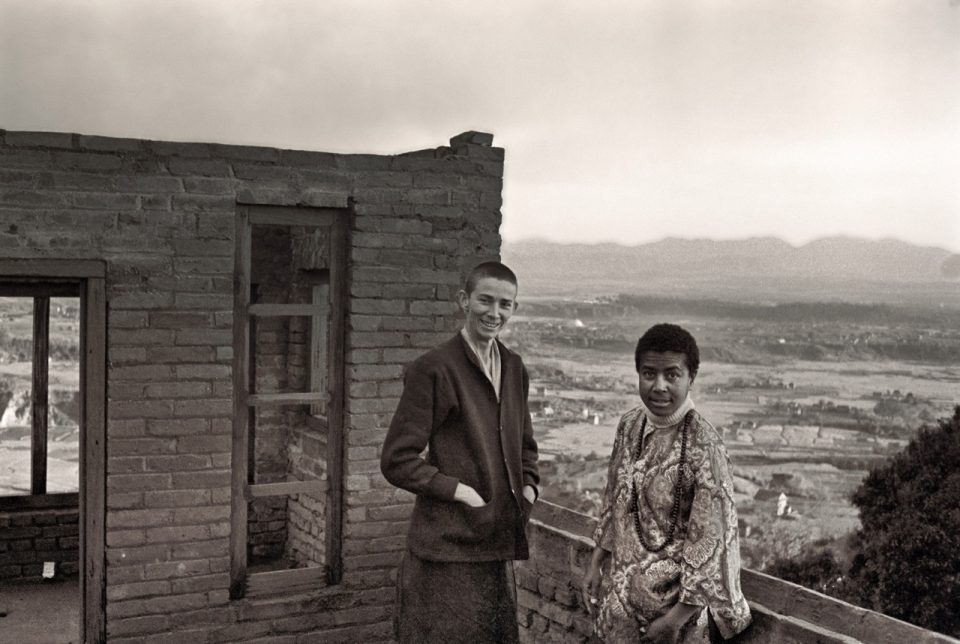

Anila Ann and Max Mathews on the roof of Kopan Monastery as the second floor is in progress, 1972. Photo courtesy of LYWA collection.

After coming back from Lawudo, Lama Yeshe started overseeing the construction works at Kopan hill. “We built resident quarters, kitchen, eating hall, and toilets and water and everything for bathing for the young monks,” Max shared. “And it took most of the ’70 and early ’71. By ’71, we had the first ordination.”

(12509_sl-3.psd) The first ordination of a group of western students, Dharamsala, India, 1970. Zina Rachevsky is in the front row between Gen Jampa Wangdu and Lama Yeshe. Ann McNeil (Anila Ann) is just to the right behind Zina, and Sylvia White is also in the back row to the right of Lama Yeshe. A student named James is second from left in back row, and Max Mathews, who also ordained that day, is curiously absent.

By 1971, there was enough space for small groups of students to come for the meditation course. Max recalled, “Westerners started getting notices to come to Kopan from the city, from everywhere around the world. And so, in ’71 we had the first course. And we had enough built that could take care of the small numbers that came. And then ’72 and ’73 was course two and three and going on.”

As Max was the principal source to support the Mount Everest Centre boys, she was concerned about a more enduring source of income, not just dependent on her personal salary. She decided to start a fashion business in Kathmandu with the first label “Samsara” and later moved her business to Delhi. Max shared, in Big Love:

Time Magazine article on Sister Max Mathew’s fashion, September 12, 1983. Photo courtesy of LYWA collection.

Business was gradually getting better. I remember the first time I went back to America for my first show. I went to this huge convention center straight from the airport and didn’t even know how to price things, but everyone was helping me. From this tiny little stand at the show I sold everything I had and got back on the plane with all this money. I would never have had the courage to do that if I hadn’t gone back to the States first with Lama in 1974. I was flying, ten feet off the ground! I knew it was all due to Lama’s blessing. My first label was Samsara, then Yeshe, and then Sister Max, which was the one that succeeded.

Max was also part of the beginnings of what we call Universal Education. She wrote a program for teachers based on many discussions with Lama Yeshe. From Big Love:

Max Mathews stayed on the tour for the duration of her school holiday leave. In Nashville, Indiana, she spent time working on an innovative education project that Lama had discussed with her. Lama had told her he believed Buddhism could be taught all around the world without using any Buddhist terms at all and in such a way that children could learn that life is impermanent, all things are interrelated and the path to life’s fulfillment involves exercising compassion and wisdom and applying appropriate methods. Max thought the first thing to do was to prepare texts in order to be able to train teachers. She wrote out a program, developed concepts and had long discussions with Lama. News of her work elicited offers from two American universities to complete a PhD in educational research but she did not accept. When the lamas left for Wisconsin, Max returned to Nepal and her job at Lincoln School.

“Her diminutive size greatly belies the vastness of her compassionate heart and spirit,” Jan Willis said about Max in 1996 in an article she wrote for Mandala magazine, “Sister Max: Working for Others.”

In Big Love, Peter Kedge explained:

Sister Max unreservedly supported Lama Yeshe financially in whatever he undertook or needed. From the day they met, Max held nothing back, unhesitatingly providing whatever Lama needed. Max offered literally everything she had with a pure heart and never a thought for herself. Every time Max received her salary check from Lincoln School it immediately went for Lama and the Mount Everest Centre one hundred percent. Later, when Max had funds from her business, it was the same. Whatever Lama needed Max provided. Max knew when Lama was exhausted and she took him away and looked after him. Max spent whatever it took, whether for a comfortable place to stay, a nice hotel, a break for retreat, a holiday, a heater, good food, school supplies, building materials, food for the school or whatever. Max was always five hundred percent there for Lama. The way Max took care of Lama was the definitive lesson in generosity and an extraordinary inspiration. No one could have done more, and Kopan would not have existed without her unstinting support.

When Lama Yeshe passed away in 1984, Mummy Max, together with other senior students, sponsored pujas for Lama Yeshe. Ven. Yarphel (John Jackson) recalled in Big Love:

Cremation of Lama Yeshe, Vajrapani Institute, California, March, 1984. Photo includes Anila Ann, Max Mathews, Massimo Corona, Geshe Thinley, and Cecily Drucker. Photo by Ricardo de Aratanha.

It was interesting to see Sister Max’s complete lack of concern for her future. She paid for all the lamas to come here and overall, we had 175 people. Station wagons were hired to pick them up, everybody ate for free during that whole week. Everything was offered. Max and some old students paid for everything. At every puja all the lamas were offered hundreds of dollars in white offering envelopes—not like the usual $20 donations. Zong Rinpoche was offered about $1,000 at each puja and the others about $300 each.

We were making as many offerings as we could. We even drove through Santa Cruz offering money to hungry people on the street. The whole thing was under the advice of Zong Rinpoche and Lama Zopa, who was like his lieutenant. Sister Max eclipsed everybody. I didn’t see what she put through on her credit card, but of the $100,000 or so that I handled, $70,000 came from her. It was Max, of course, who had unhesitatingly paid the $15,000 bill from Cedars-Sinai Hospital.

The Car that Saved Mount Everest Centre

Max with her 1932 Hudson. Photo credit: Chitraker.

Shortly after they were built, two 1932 Hudson Phaeton cars were shipped to Calcutta, then carried by porters over the mountains into Nepal. That was the only way to bring vehicles into Nepal before the Raj Path was built in 1956. One of the vehicles was for the King of Nepal and the other was for the Prime Minister.

The history of at least one of the 1932 Hudson’s is really quite remarkable.

Max Mathews bought one of them from the King’s palace in the late 1960s. She recalled discovering that this car was available for purchase, “Wow, my heart starts racing and I have to get that car. I buy it, and I drive it around Kathmandu on the unpaved roads. There are no roads on Kopan at all, so that’s something we have to deal with.”

The car fell into disrepair and in 1972 Max asked Peter Kedge if he knew anything about cars. Indeed, he did! From age eleven, he had worked for two years in a bicycle shop, then at a garage during every school holiday until he graduated from university ten years later. By that time, he had spent more time working on cars than driving them. She asked whether he could help get the Hudson back into running condition. The car was stored in one of the Rana homes in Tintuli that Max was renting just outside Boudhanath. Peter spent three months at Tintuli with very few tools but did get the car running well again.

In the meantime, Max was the main benefactor supporting the early growth of Kopan Monastery north of Boudhanath. Peter stayed on at Kopan after the second course in 1972. He wanted to help and there was always work to do—either securing supplies for building the gompa, driving supplies to Kopan, managing the laborers, etc.

Max’s entire Lincoln School salary supported not only the early building at Kopan, but the entire education and maintenance of about 50 young Sherpa and Tibetan monks in the Mount Everest Centre School. In the summer months the school was held in Lawudo and in the Winter months the school would come down to Kopan where it was less cold.

In the Summer of 1973 an emergency message came down from Lawudo to Kopan saying that the school had run out of food and money.

The restored 1932 Hudson. Photo courtesy of Calvin Buchanan.

As always, taking full responsibility without any reservation Max immediately said to Peter, “Sell the Hudson.”

Peter placed an advertisement in the Rising Nepal newspaper and a gentleman from the U.S. Embassy responded, viewed the car, and purchased it. The proceeds from the sale of the Hudson saved the school and supported the 50 children and their teachers for quite a while.

The car was shipped through Calcutta to the U.S. and eventually ended up with a Hudson collector in Texas. A few years ago, the car’s owner, a collector who has more than twenty such vehicles, traveled to Santa Fe to meet Max and find out more about the car’s history. Since that time, the car has been completely renovated back to the original factory condition and colors.

Words of Thanks and Reverence for Max Mathews

On hearing the news of Mummy Max’s passing, many old and new friends around the world expressed moving tributes of thanks and reverence for Max. Here we share some of these sentiments:

Max Mathews, 1974, Berkeley. Photo by Judy Weitzner.

“We rejoice how Mummy provided unconditional and essential support for the Lamas’ Western Dharma project as envisioned by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and remember how we are dependent upon Mummy Max for her mandala role in bringing the Dharma of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche to the West.” —From the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

“Max’s dedication led her to play a crucial role in establishing and funding Kopan Monastery in the 1970s. Her generosity created a haven for spiritual seekers. Her passing marks the loss of a remarkable soul whose philanthropy touched many lives. Tonight, in the presence of Kyabje Khen Rinpoche, all the monks gathered to pray for her to be reborn in a higher realm and eventually attain Nirvana.” —From Kopan Monastery

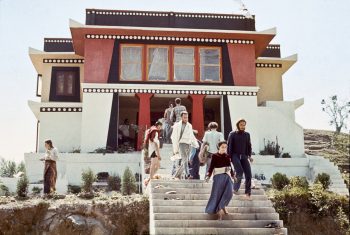

Front view of Kopan Monastery 1972, with students on the steps. Photo courtesy of the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

“It is impossible to imagine what Kopan (and the FPMT) might have been without her. When I first arrived at Kopan in the fall of 1972, Sister Max was single-handedly supporting the Lamas, thirty or so young Sherpa monks there at the time and the entire monastery infrastructure. She was a teacher at the American Lincoln School in Kathmandu and donated her entire salary to Kopan. Her generosity and devotion to Lama and Rinpoche were exemplary and inspiring and motivated many of us to devote ourselves to trying to emulate her in helping the Lamas in their mission to preserve and spread the Dharma for the enlightenment of all sentient beings. Today we see the incredible results. It would not have happened without her.”—From Nick Ribush

The Final Days: A Peaceful Transition

FPMT center, Thubten Norbu Ling, offered support to Max in her final days. They shared this moving account of her passing.

Max at the end of her life. Photo shared by Losang Dragpa Centre FPMT Facebook page

As Mummy Max celebrated her 90th birthday, little did we know that her journey on this earth was nearing its end. In her final days, the volunteers from The Buddhist Center took turns by her side, reciting Medicine Buddha Puja, The Eight Prayers to Benefit the Dead and Dying, The Vajra Cutter Sutra and many others. Messages, help and encouragement kept coming from around the world, and we spent the days doing practice, playing Lama Zopa’s mantras in the background and showing Mummy Max pictures of the lamas and holy objects.

Although weak, she was clear and attentive, holding our hands and sharing big smiles and hugs, whenever she woke up. She did not display any sign of pain, anxiety, or discomfort until her last breath. Her transition from this world was marked by a profound sense of peace, leaving those by her side feeling connected, uplifted, and inspired.

When Mummy Max stopped breathing, we were prepared. We managed to identify a local funeral home, which respected the Tibetan Buddhist customs. She was able to remain undisturbed in her apartment until she concluded her final meditation. The atmosphere in the room was clear and vivid, and Geshe Tenzin Zopa said that there was no doubt that Mummy Max was in the clear light meditation. At that time, we did practice in her room day and night, dedicating for her most fortunate rebirth. After two days, Geshe la confirmed that Mummy Max’s meditation came to an end.

Geshe la recited the Guhyasamaja Root Text and other prayers recommended before the removal of the deceased person’s body. Before Mummy Max’s worldly remains left the apartment, she was turned 3 times clockwise. Geshe la explained that according to Tibetan customs, sending the body off is like losing a precious gem and turning it three times allows for the precious energy to be preserved in our world system. Geshe la also checked for the best day suitable for cremation, which the funeral home agreed to honor.

Mummy Max, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2022. Photo by Steve Nadeau

“Mummy Max’s legacy lives on in our hearts, reminding us that through love, compassion and sincere practice, each of us can transcend the limitations of our human existence. As we reflect on Mummy Max’s life, we extend our deepest gratitude to our resident teacher, Geshe Thubten Sherab, Geshe Tashi Dhondup, Geshe Tenzin Zopa, and all the volunteers and supporters who selflessly dedicated their time and resources to ensure her peaceful and meaningful transition. Their unwavering commitment to her spiritual and physical well-being is a testament to the bonds of family and community that unite us all.” —Thubten Norbu Ling, Santa Fe FPMT Center, from a Facebook message following Max’s passing.

You can learn more about Max’s life in this 2020 interview, where she tells her own story about her relationships with the lamas. You can also read about Mummy Max’s first trip to Lawudo, as told by her old friend Judy Weitzner; find an excerpt about her in Big Love; an article by Jan Willis from Mandala magazine (1996), “Sister Max: Working for Others”; and an article from the Kathmandu Post, “The Enduring Legacy of Sister Max”.

Big Love, written by Adele Hulse, is the official, authorized biography of Lama Yeshe containing personal stories of the lamas and the students who learned, lived and traveled with them, as well as more than 1,500 photos dating back to the 1960s.

Please pray that Mummy Max Mathews may never ever be reborn in the lower realms, may she be immediately born in a pure land where she can be enlightened or to receive a perfect human body, meet the Mahayana teachings and meet a perfectly qualified guru and by only pleasing the guru’s mind, achieve enlightenment as quickly as possible. More advice from Lama Zopa Rinpoche on death and dying is available, see Death and Dying: Practices and Resources (fpmt.org/death/).

- Tagged: big love, fpmt history, mummy max, obituaries, obituary, road to kopan, ven max mathews

16

Ven. Ngawang Yonten, “Ashang,” 2023. Photo by Ven. Sarah Thresher.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s uncle, Ven. Ngawang Yönten (affectionately known as Ashang, which means, “maternal uncle”) passed away peacefully at Lawudo, Nepal, on the morning of July 7, 2024. He was 98 years old and most likely one of the last of the local Sherpas to have known both Lawudo Lamas. Please read this beautiful account of Ashang’s life, written by Ven. Sarah Thresher with input and details from Anila Ngawang Samten, Gelong Ngawang Nyendak, Jamyang Wangmo (including consultation of The Lawudo Lama), and Ven. Tsultrim,

To visitors at Lawudo, Ashang was a constant presence at the lower retreat huts where he recited mantra continually from morning to night, stopping only to eat, sleep or go to the bathroom. He seemingly had no attachment to worldly things and Rinpoche would often fondly relate stories from his life of practice (see The Lawudo Lama).

Ashang was born in Thame in 1926, the Year of the Tiger. He was the youngest of six children—three girls and three boys—and his father (Rinpoche’s grandfather) died while he was still in the womb. Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s mother, Nyima Yangchen was the eldest child in the family. The family had five yaks and when he was young he would take care of them, bringing them up to Tengbo, and also help Rinpoche’s father with their yaks. When Rinpoche’s father passed away leaving the mother with three small children, he helped as much as he could.

In 1955, when he was in his late 20s, Ashang became very sick and nobody could help. Two years later when Rinpoche’s uncles decided to go to Tibet for pilgrimage, Ashang also came along, bringing their luggage on his five yaks as far as Dingri Ganggar. There he went to see a famous Tibetan doctor, but the doctor couldn’t help him. After visiting another doctor who also couldn’t cure him, he decided to go to Dza Rongphu to see Trulshik Rinpoche. Trulshik Rinpoche advised him that his sickness was due to karmic obscuration and could not be cured by medicines but only through purification practices. Ashang requested to be ordained as a monk and Trulshik Rinpoche advised him to do the preliminary practices first. Ashang stayed six months at Rongphu receiving teachings and then took getsul vows. He returned to Khumbu with his five yaks loaded with salt and decided to sell the animals and devote himself fully to Dharma practice.

Ashang, Amala (Rinpoche’s mother) and Ani Ngawang Samten (Rinpoche’s sister) in 1983.

As the youngest son, Ashang was responsible to take care of his mother (Rinpoche’s grandmother) who was now old and blind and could not be left alone. He obtained permission from Charok Lama Kushog Mende to build a small hut under the cliff at Charok and he moved there with his mother. The hut was very small so Ashang would spend the night in a small square meditation box while his mother slept on a wooden bench next to the fireplace. He did prostrations on a wooden board outside the hut. In addition to his own Dharma practice, he did all the cooking, collected firewood and fetched water because his mother could do nothing except recite mani mantras.