- Home

- FPMT Homepage

Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition

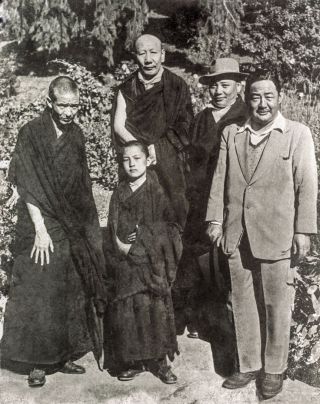

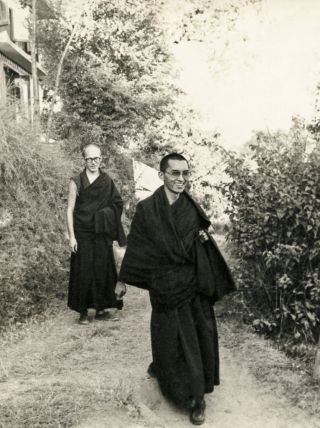

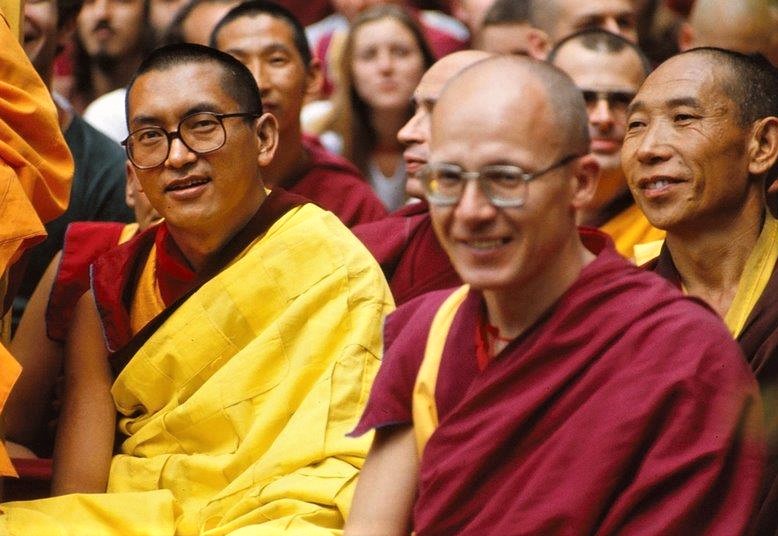

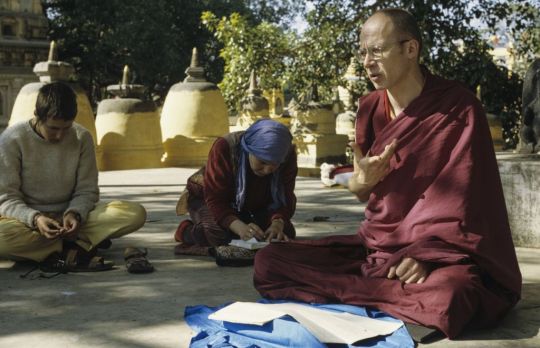

The FPMT is an organization devoted to preserving and spreading Mahayana Buddhism worldwide by creating opportunities to listen, reflect, meditate, practice and actualize the unmistaken teachings of the Buddha and based on that experience spreading the Dharma to sentient beings. We provide integrated education through which people’s minds and hearts can be transformed into their highest potential for the benefit of others, inspired by an attitude of universal responsibility and service. We are committed to creating harmonious environments and helping all beings develop their full potential of infinite wisdom and compassion. Our organization is based on the Buddhist tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa of Tibet as taught to us by our founders Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche.

- Willkommen

Die Stiftung zur Erhaltung der Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) ist eine Organisation, die sich weltweit für die Erhaltung und Verbreitung des Mahayana-Buddhismus einsetzt, indem sie Möglichkeiten schafft, den makellosen Lehren des Buddha zuzuhören, über sie zur reflektieren und zu meditieren und auf der Grundlage dieser Erfahrung das Dharma unter den Lebewesen zu verbreiten.

Wir bieten integrierte Schulungswege an, durch denen der Geist und das Herz der Menschen in ihr höchstes Potential verwandelt werden zum Wohl der anderen – inspiriert durch eine Haltung der universellen Verantwortung und dem Wunsch zu dienen. Wir haben uns verpflichtet, harmonische Umgebungen zu schaffen und allen Wesen zu helfen, ihr volles Potenzial unendlicher Weisheit und grenzenlosen Mitgefühls zu verwirklichen.

Unsere Organisation basiert auf der buddhistischen Tradition von Lama Tsongkhapa von Tibet, so wie sie uns von unseren Gründern Lama Thubten Yeshe und Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche gelehrt wird.

- Bienvenidos

La Fundación para la preservación de la tradición Mahayana (FPMT) es una organización que se dedica a preservar y difundir el budismo Mahayana en todo el mundo, creando oportunidades para escuchar, reflexionar, meditar, practicar y actualizar las enseñanzas inconfundibles de Buda y en base a esa experiencia difundir el Dharma a los seres.

Proporcionamos una educación integrada a través de la cual las mentes y los corazones de las personas se pueden transformar en su mayor potencial para el beneficio de los demás, inspirados por una actitud de responsabilidad y servicio universales. Estamos comprometidos a crear ambientes armoniosos y ayudar a todos los seres a desarrollar todo su potencial de infinita sabiduría y compasión.

Nuestra organización se basa en la tradición budista de Lama Tsongkhapa del Tíbet como nos lo enseñaron nuestros fundadores Lama Thubten Yeshe y Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

A continuación puede ver una lista de los centros y sus páginas web en su lengua preferida.

- Bienvenue

L’organisation de la FPMT a pour vocation la préservation et la diffusion du bouddhisme du mahayana dans le monde entier. Elle offre l’opportunité d’écouter, de réfléchir, de méditer, de pratiquer et de réaliser les enseignements excellents du Bouddha, pour ensuite transmettre le Dharma à tous les êtres. Nous proposons une formation intégrée grâce à laquelle le cœur et l’esprit de chacun peuvent accomplir leur potentiel le plus élevé pour le bien d’autrui, inspirés par le sens du service et une responsabilité universelle. Nous nous engageons à créer un environnement harmonieux et à aider tous les êtres à épanouir leur potentiel illimité de compassion et de sagesse. Notre organisation s’appuie sur la tradition guéloukpa de Lama Tsongkhapa du Tibet, telle qu’elle a été enseignée par nos fondateurs Lama Thoubtèn Yéshé et Lama Zopa Rinpoché.

Visitez le site de notre Editions Mahayana pour les traductions, conseils et nouvelles du Bureau international en français.

Voici une liste de centres et de leurs sites dans votre langue préférée

- Benvenuto

L’FPMT è un organizzazione il cui scopo è preservare e diffondere il Buddhismo Mahayana nel mondo, creando occasioni di ascolto, riflessione, meditazione e pratica dei perfetti insegnamenti del Buddha, al fine di attualizzare e diffondere il Dharma fra tutti gli esseri senzienti.

Offriamo un’educazione integrata, che può trasformare la mente e i cuori delle persone nel loro massimo potenziale, per il beneficio di tutti gli esseri, ispirati da un’attitudine di responsabilità universale e di servizio.

Il nostro obiettivo è quello di creare contesti armoniosi e aiutare tutti gli esseri a sviluppare in modo completo le proprie potenzialità di infinita saggezza e compassione.

La nostra organizzazione si basa sulla tradizione buddhista di Lama Tsongkhapa del Tibet, così come ci è stata insegnata dai nostri fondatori Lama Thubten Yeshe e Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Di seguito potete trovare un elenco dei centri e dei loro siti nella lingua da voi prescelta.

- 欢迎 / 歡迎

简体中文

“护持大乘法脉基金会”( 英文简称:FPMT。全名:Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) 是一个致力于护持和弘扬大乘佛法的国际佛教组织。我们提供听闻,思维,禅修,修行和实证佛陀无误教法的机会,以便让一切众生都能够享受佛法的指引和滋润。

我们全力创造和谐融洽的环境, 为人们提供解行并重的完整佛法教育,以便启发内在的环宇悲心及责任心,并开发内心所蕴藏的巨大潜能 — 无限的智慧与悲心 — 以便利益和服务一切有情。

FPMT的创办人是图腾耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。我们所修习的是由两位上师所教导的,西藏喀巴大师的佛法传承。

繁體中文

護持大乘法脈基金會”( 英文簡稱:FPMT。全名:Found

ation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition ) 是一個致力於護持和弘揚大乘佛法的國際佛教組織。我們提供聽聞, 思維,禪修,修行和實證佛陀無誤教法的機會,以便讓一切眾生都能 夠享受佛法的指引和滋潤。 我們全力創造和諧融洽的環境,

為人們提供解行並重的完整佛法教育,以便啟發內在的環宇悲心及責 任心,並開發內心所蘊藏的巨大潛能 — 無限的智慧與悲心 – – 以便利益和服務一切有情。 FPMT的創辦人是圖騰耶喜喇嘛和喇嘛梭巴仁波切。

我們所修習的是由兩位上師所教導的,西藏喀巴大師的佛法傳承。 察看道场信息:

- FPMT Homepage

- News/Media

-

- Study & Practice

-

-

- About FPMT Education Services

- Latest News

- Programs

- New to Buddhism?

- Buddhist Mind Science: Activating Your Potential

- Heart Advice for Death and Dying

- Discovering Buddhism

- Living in the Path

- Exploring Buddhism

- FPMT Basic Program

- FPMT Masters Program

- FPMT In-Depth Meditation Training

- Maitripa College

- Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo Translator Program

- Universal Education for Compassion & Wisdom

- Online Learning Center

-

- Prayers & Practice Materials

- Overview of Prayers & Practices

- Full Catalogue of Prayers & Practice Materials

- Explore Popular Topics

- Benefiting Animals

- Chenrezig Resources

- Death & Dying Resources

- Lama Chopa (Guru Puja)

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Life Practice Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Practice Series

- Lamrim Resources

- Mantras

- Prayer Book Updates

- Purification Practices

- Sutras

- Thought Transformation (Lojong)

- Audio Materials

- Dharma Dates - Tibetan Calendar

- Translation Services

- Publishing Services

- Ways to Offer Support

- Prayers & Practice Materials

-

- Teachings and Advice

- Find Teachings and Advice

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Advice Page

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche: Compendium of Precious Instructions

- Lama Zopa Rinpoche Video Teachings

- ༧སྐྱབས་རྗེ་བཟོད་པ་རིན་པོ་ཆེ་མཆོག་ནས་སྩལ་བའི་བཀའ་སློབ་བརྙན་འཕྲིན།

- Podcasts

- Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

- Buddhism FAQ

- Dharma for Young People

- Resources on Holy Objects

- Teachings and Advice

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- Centers

-

- Teachers

-

- Projects

-

-

-

-

*If a menu item has a submenu clicking once will expand the menu clicking twice will open the page.

-

-

- FPMT

-

-

-

-

-

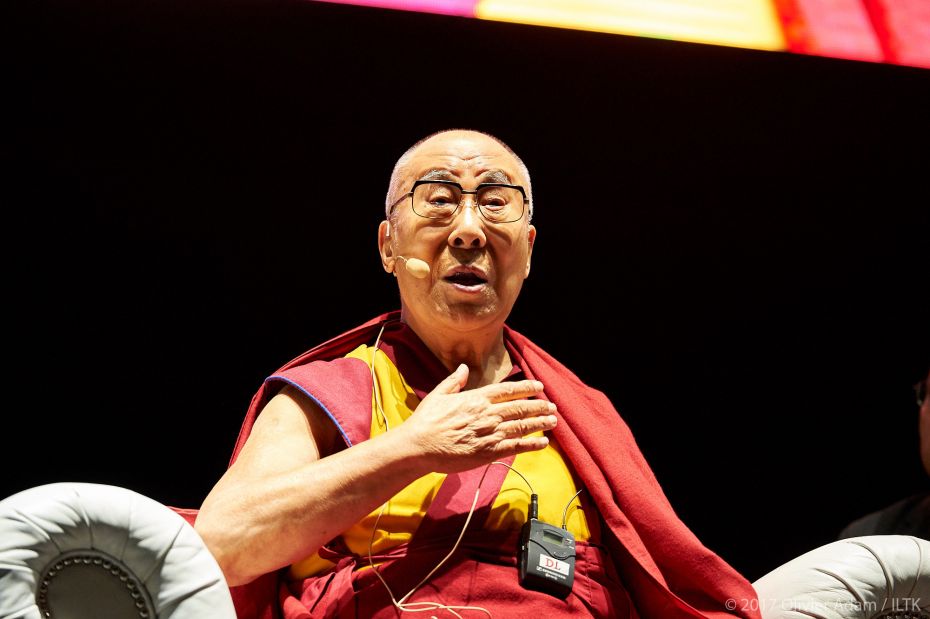

Whether one believes in a religion or not, and whether one believes in rebirth or not, there isn’t anyone who doesn’t appreciate kindness and compassion.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

-

-

-

- Shop

-

-

-

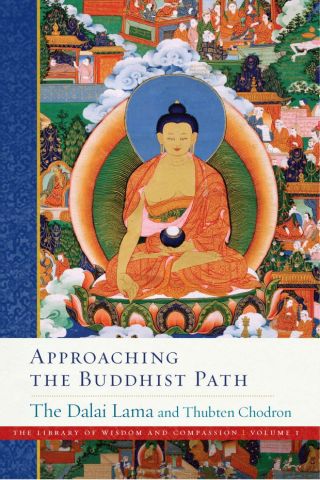

The Foundation Store is FPMT’s online shop and features a vast selection of Buddhist study and practice materials written or recommended by our lineage gurus. These items include homestudy programs, prayers and practices in PDF or eBook format, materials for children, and other resources to support practitioners.

Items displayed in the shop are made available for Dharma practice and educational purposes, and never for the purpose of profiting from their sale. Please read FPMT Foundation Store Policy Regarding Dharma Items for more information.

-

-

In-depth Stories

31

Pilgrimage to the Hidden Valley of Tsum, Nepal

Frayed prayer flags flying over Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

In the remote borderlands of the high Himalayas, several valleys are said to be beyul—hidden or secret valleys—only open to those with very pure minds and hearts. According to ancient scriptures, they were established by Guru Rinpoche, the 8th-century Indian saint credited with spreading Buddhism into the Himalayas and Tibet.

In the 17th century the Tsum valley that branches off the Buri Gandaki River towards the north of Ganesh Himalaya (Mountain) in upper Gorkha District, Nepal, was named Beyul Kyimolung. Perhaps one of Nepal’s most beautiful valleys, it is cut off from the southern lowlands of Nepal by deep, forested gorges and swift rivers, and from Tibet in the north by snow-covered passes.

In May 2018 a group of twenty-two pilgrims, including Losang Dragpa Center resident teacher Geshe Jampa Tsundu, Tsum Project coordinator and former Rinchen Jangsem Ling secretary Low Yuet Kiew (“YK”), and FPMT Southeast Asia regional coordinator Selina Foong traveled together to Tsum, Nepal. Here, Selina shares her experience of the pilgrimage.

When I first heard that my friend YK, who is a member of two FPMT centers in Malaysia—Losang Dragpa Centre and Rinchen Jangsem Ling—was organizing a trip to the hidden valley of Tsum, Nepal, my hand shot up so fast that I just about dislocated my shoulder. Only later did random thoughts start to niggle. Will the helicopter ride cost a fortune? What sort of altitude are we talking about? The last time I hiked up any mountain (more like a hill by Nepal standards) was several years ago—how will my knees, now thrashed, hold up?

All doubts dissipated as our departure date neared. The time has come for sheer excitement! Final trip arrangements, lunch at Khachoe Ghakyil Ling Nunnery in Kathamandu, Nepal, a trial climb up to 2,700 meters (8,858 feet) altitude outside Kathmandu, kora at Boudha Stupa, and two peaceful nights in Kopan Monastery brought us to the day, Thursday, May 10, 2018, when we left the world behind and entered a blessed realm filled with riches far beyond our imagination.

Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

Ethereal waterfalls tumbling down rugged mountains so steep they were just about vertical. Jagged snowy peaks luminous from the rays of the sun as far as the eye could see. A lone eagle of majestic wing span, slowly soaring over the vast valley below. Holy caves latent with the enlightened energy of past meditators, including Milarepa and Geshe Lama Konchog. The inspiring spirituality and genuine kindness of virtually everybody we met. Simply recalling all this is making my heart ache with the sweetest yearning.

It took four helicopters to ferry twenty-two of us from Kathmandu to Tsum. They were not kidding about strict weight controls. Only 10kg (22 lbs) of luggage each, which really wasn’t much considering that we would be staying at Rachen Nunnery in Tsum for one week. Inevitably, manic and desperate curtailing went on in many a Kopan bedroom the night before departure!

I will never forget my first sight of Rachen Nunnery. With jaws already slack from forty minutes of gaping at one spectacular mountain after another, Geshe Jampa Tsundu suddenly exclaimed, “Look! Rachen!”

Rachen Nunnery seen from a helicopter, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

Geshe-la was almost as excited as we were! It had been several years since he himself was there as resident teacher, and he was so looking forward to seeing all the monks and nuns again.

I stared into the distance. “Yes, I see it!” A low flat structure laid out in a huge square sharply contrasted against an expansive white wonderland. After years of hearing, reading, and talking about this place, I could hardly believe that we were actually about to land in it.

Landing at Rachen Nunnery, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

With my first step out of the helicopter I got a jolt. It was cold! The morning’s snowfall had turned into freezing drizzle by the time my helicopter (number three) landed. An auspicious welcome no doubt, but this blast of cold after the Kathmandu heat sent shock waves through my undoubtedly tropical heart.

Greetings, khatas, shouts of delight,—then we all hurried along into the warmth of the dining room for very hot tea. And so passed our first day at Rachen.

Pilgrimage group with Drukpa Rinpoche, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

Among a blur of happiness and wonder was a group audience with Drukpa Rinpoche, who in his past life had founded both Mu Monastery and Rachen Nunnery. This was an unexpected bonus, as Rinpoche normally resides in India these days and “just happened” to be at Rachen. How wonderful!

We also toured the extensive nunnery grounds, which included the original and new gompa buildings, as well as an evocative house built by Geshe Lama Konchog himself.

Yak carrying loads up a trail, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

And on both sides of this flat valley, towering mountains pushed ever upwards into a wide open sky.

Natural splendor aside, the harshness of everyday life was also evident. Food had to be grown at the nunnery grounds or picked from the wild, and occasional one-day walks through the mountains into Tibet were necessary in order to obtain more groceries.

To keep warm, firewood had to be gathered from the nearby jungles (“nearby” being a relative term in Nepal) and hauled back to the nunnery. There was only solar energy to rely on, so needless to say, cloudy days meant icicles in the shower for those foolhardy enough to make the attempt.

Our second day dawned bright and clear, and we joined the nuns in their daily Tara Puja before setting off on our first hike.

First up, Milarepa’s Cave of the Doves! Here, dakinis had transformed into doves in order to listen to the Dharma from Milarepa. There were three separate but adjacent parts—a meditation gompa, a small cave with his very clear footprint on a large rock, and another small gompa with holy statues.

Leaving from Rachen Nunnery for the first hike, to Milarepa Cave of Doves, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

How moving to peer out from those dim tiny spaces towards the endless snowy peaks beyond, and realize that the great saint Milarepa would have done much the same centuries ago, as he meditated on the nature of reality! Galvanized and inspired, I recalled this beautiful line from Calling the Lama from Afar: “Magnificently glorious guru, please bless me to abide one-pointedly in practice in isolated places, not having any hindrances to my practice.”

On our way down, we stopped at another holy cave. Here, the great yogi Geshe Lama Konchog had meditated. Gazing at the piles of stones and then further into the darkness, the tranquility was palpable.

Visiting Geshe Lama Konchog’s retreat cave below Milarepa’s Cave of Doves, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

As it turned out, these holy places had a way of suspending the normal passage of time in more ways than one. As we trekked back and looked at our watches, we were suddenly startled. What was to have been an easy walk this morning had turned into a five-hour expedition! Whoops! Blame it on all the posing and photos!

We sped up, got back, gulped down our very late lunch, then changed into brand new orange TSUM t-shirts for the grand opening of the Library of Nalanda Wisdom for Rachen Nunnery, an electronic library consisting of iPads and tablets that each of us had carried to Tsum from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, fully loaded with prayers and teachings. The nuns were so excited! What a happy afternoon it was, with speeches, laughter, applause, balloons, balloons, and yet more balloons.

Grand opening of the electronic library at Rachen Nunnery, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

A good night’s sleep set us up to walk three times further the next day.

Big excitement—we were going to Apey and Mochung’s house for lunch! Parents of both Tenzin Phuntsok Rinpoche (the reincarnation of the late Geshe Lama Konchog) and Thubten Rigsel Rinpoche (the reincarnation of the late Khensur Rinpoche Lama Lhundrup Rigsel), they were so endearingly kind, bending over backwards to return early to Tsum from Kathmandu, just to meet us and cook a huge lunch for us all.

Geshe Jampa Tsundu thanking Apey and Mochung after lunch, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

By the time this feast was over, however—and no doubt recalling our dismal pace yesterday—both Geshe Tsundu and Gen Tenpa Choeden decided that we would never make it to the Geshe Lama Konchog retreat cave Gaden Gompa behind Apey and Mochung’s house and be back at the nunnery before nightfall. Disappointment all round! But we were also grateful that they were so concerned for our safety.

Hiking in Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

In any case, the trek back to Rachen was gorgeous as we took a different route through the jungles and then along the river, accompanied by strains of “Hala Hala ling ling chura chura ling ling! Hara hara ling ling!” sung by our jolly companion nuns.

By the time we all trekked (or staggered) back to the nunnery, our dear lamas must have taken pity on us. We probably looked truly bedraggled! And so it was declared: our program would be adjusted to allow the next day to be free and easy.

This was music to our ears! It also posed a golden opportunity for a few energetic and kiasu pilgrims—six of us to be exact.

Cornering Geshe Tsundu that evening, he finally agreed to lead us back the very next day to Gaden Gompa, where Geshe Lama Konchog had meditated for many years and completed 2,000 nyung nä retreats. But there were two conditions: we had to walk fast this time, and we could not stop every ten seconds to take photos! Like excited children, we agreed. Which was why the very next day, the six of us trotted off along with our Sangha guides at 7:46 a.m. sharp and obediently kept up the pace with military precision.

It turned out to be a very special day. The magnitude of the places we would be visiting that day was not lost on me, and I had made fervent prayers before leaving that we would have the karma to complete the day’s pilgrimage without mishap.

Hiking in Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

Finally, after an arduous climb, we arrived. All chatter stopped; a gentle hush fell.

As we entered the Geshe Lama Konchog retreat cave Gaden Gompa, I thought of every sentient being—all of them having played a role in bringing me to this point, in this life—and felt overwhelming gratitude toward them all. This experience was only possible in dependence upon all others, and so it was for all others that I experienced it.

Khata after khata was offered, as I also thought about all my dear Dharma friends and travel companions who did not make it that day. We spent a long time there inside the small hut as well as the open area behind it, where Geshe Lama Konchog’s robes and belongings remain sealed in a stone vault. Geshe Tsundu led the prayers and meditation before we finally hung our prayer flags and departed.

View from Geshe Lama Konchog’s retreat hut Gaden Gompa, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

Thinking that was it, Geshe Tsundu was about to lead us back down for lunch and the return journey. But after this extraordinary experience, it was plain we were keen for more! In the end, it didn’t take much convincing for Geshe-la as well as Apey to lead us to the Hayagriva cave further along the mountain.

We took turns entering the small cave, where a tiny creek flowed, and an amazing self-emanating torma in a deep shade of red was clearly evident on the rocks. Wow! We had to spread ourselves out flat on the rocks in order to reach the torma and taste some of the holy water. What wonderful blessings!

We returned to Rachen with our hearts singing and bellies filled to the brim after a late lunch at dear Apey and Mochung’s house (again!). It was a merry reunion with everyone in the dining room that evening, as we all recounted the day.

Some had returned to the second Geshe Lama Konchog cave below Milarepa’s Cave of the Doves to spend several happy hours. Others trekked to a nearby village shop, to stock up on basic groceries for the nuns, before returning to cook up a feast for everyone. The fried rice tasted amazing!

Tractor and trailer ride, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

Which brings us to our second to last day in Tsum—the day of the tractor. It was a day none of us would ever forget.

Tractor? Yes, tractor. And us in a trailer, with no suspension, pulled by said tractor. Us, meaning approximately twenty not particularly tiny people. Why on earth? Because it was raining solidly from 3 a.m., and there was no way we were going to hike the 30 kilometers (19 miles) round-trip up to Mu Monastery and back in a single day, let alone in cold wet conditions. Nothing for it. As Gen Tenpa Choeden announced, “Die die also must go!”

This got me thinking that Mu Monastery, at an altitude of 3,700 meters (12,139 feet) and in the same direction as Tibet, must really be a fantastically special place.

Oh, the obstacles we encountered in trying to visit Mu! Already postponed twice, it almost looked like we would not be able to go at all—until this tractor and trailer combination (more glamorously referred to as the “Ferrari” by YK) came to our rescue.

In actual fact, “rescue” was the last thing that came to mind. As we banged and crashed through impossible terrain, including wild rivers complete with rocks and raging rapids, at times mere inches from steep ravine edges, it was quite a wonder that we didn’t get transported right into our next lives instead.

There we were—hollering and yowling, sometimes in fits of laughter and other times in sheer terror—squashed together like sardines and getting flung around like rag dolls. Such retrospective fun! Wonderful collective karma, right travel buddies?

Mu Monastery monks awaiting the pilgrims’ arrival, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

But it was so worth it. Mu Monastery was indeed special. Old and isolated, it was like nothing I had ever experienced. Under leaden skies, heavy mist, and enveloped by sharp cold air, I found myself floating in a dream-like world belonging to a different time.

The elderly resident monks were into their first day of the annual Saka Dawa nyung nä retreat in their dark and evocative gompa. We will forever be grateful to have been a small part of it all.

Mu Monastery gompa, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

A fitting end to our stay at Tsum was joining the Rachen nuns on the second day of their own nyung nä retreat. As we evoked One-Thousand Arm Avalokiteshvara in this beautiful practice, I prayed for the holy Dharma to flourish in this and all worlds. May the lives of our gurus be long and healthy. May they return to teach us over and over again, until samsara is utterly emptied of all beings.

A big thank you to Gen Tenpa Choeden, Geshe Tsundu, Geshe Nyima, all the Sangha at Rachen Nunnery, Mu Monastery, Khachoe Ghakyil Ling Nunnery, Kopan Monastery, Tsum Project coordinator YK, and all my wonderful travel companions. And a special mention to Geshe Tenzin Zopa, original Tsum Project coordinator and former resident geshe at Losang Dragma Center, who was so instrumental behind the scenes in ensuring that this would be a trip for us to remember for the rest of our lives.

Rachen Nunnery’s new gompa, Tsum, Nepal, May 2018. Photo by Tsum pilgrimage participant.

Here’s to our next pilgrimage. And we’d better choose somewhere cold so that we can all wear the new Marmot gear we amassed upon our return to Kathmandu!

Read Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s advice for pilgrimage:

https://fpmt.org/wp-content/uploads/teachers/zopa/advice/Pilgrimage_Advice.pdf

- Tagged: geshe jampa tsundu, geshe lama konchog, in-depth stories, mu monastery, nepal, pilgrimage, rachen nunnery, selina foong, tsum, tsum project, tsum valley

30

MAITRI Charitable Trust: Service in the Land of Noble Truths

MAITRI paramedical staff member Arun disbursing supplements to pre and post-natal mothers during a Child Mobile Clinic, south of Bodhgaya, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

Phil Hunt, coordinator of FPMT probationary project Enlightenment for the Dear Animals, shares about his visit in early 2018 to FPMT project MAITRI Charitable Trust in Bodhgaya, India.

Heading out at dawn through the outskirts of Bodhgaya on one of MAITRI Charitable Trust’s regular Mother & Child mobile clinics, I could quietly witness the pollution and poverty all too apparent at the edges of towns and the main roads.

It’s not the romantic image one would like to have of the place where the Buddha walked and taught all those years ago. Bodhgaya is in Bihar, and Bihar has one of the highest incidences of leprosy, TB, and infant mortality, and one of the lowest literacy rates in India.

Adriana Ferranti reviewing a new leprosy case, MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

The work that MAITRI does is not romantic either. Identifying people with leprosy, cleaning and dressing ulcers in flesh damaged due to localized deadening of the nerves, identifying people with tuberculosis (TB), collecting and analyzing sputum samples, assisting undernourished TB patients, or prenatal mothers, or newborn babies, and treating injured, maimed, and sick animals that have nowhere else to go.

On a foggy winter morning where the sun didn’t show up at all, the mobile clinic team headed away from the hubbub around Bodhgaya where His Holiness the Dalai Lama had arrived. Down the highway towards the Delhi-Kolkata Trunk Road. Past poverty and the grime you get when construction has arrived, incomplete, but with few of the benefits. The intersection with the Trunk Road is rubbish-filled, noisy, scattered with long-distance trucks and generally ugly.

MAITRI staff member testing a patient’s sputum sample for tuberculosis, MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

His Holiness had come to teach on the Four Noble Truths. And we all know the first one is the Truth of Suffering. Here it is impossible to miss. His Holiness’ teachings were particularly responding to an Indian request, and he highlighted again and again how it is the Indian tradition that the Tibetans inherited and preserved, and that is now returning to its homeland. One of those traditions is cherishing others, based on critical analysis of its benefits.

Looking around Bodhgaya and surrounding districts at the poverty and ignorance, how could you possibly think you could make any impact? Yet these are the sentient beings Buddhists have pledged to bring to enlightenment, that Christians go to serve following the example of Jesus, that the left side of politics works to uplift, that the right side of politics promises to benefit through a ‘trickle down’ economy. They are the global neighbors with whom we have responsibility to share the riches of the world fairly. Indeed, these are the beings that might have been our direct neighbors if our karma had been very slightly different.

MAITRI staff reviewing an x-ray with the patient, MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

Is trying to help simply a futile gesture? Some token feel-good exercise? It is easy to think this way. Yet we all know of how special it was to receive help when we needed it. Not a thousand other people, not five desperately needy, not a stranger over there. Us. You. Me. When someone had stopped to help us when we thought nobody would. That individual out of so many who happens to be feeling, thinking, wishing to be free of this particular suffering. To be helped, how wonderful! What relief!

Perhaps this is what pushes MAITRI staff to work so hard, understanding that some of these individuals can be helped and MAITRI can do it.

MAITRI staff conducting leprosy training in a village, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

The 16 Guidelines for Life also come to mind when I see MAITRI workers in action.

Humility—the founding and ongoing recognition that only the government can possibly reach every citizen, therefore a charity that works in partnership with the government will be more effective to render assistance to those who fall through the cracks. MAITRI is the only organization authorized by the Government of Bihar to assist the District Leprosy Office in Gaya District.

Patience—not just with everything that Bihar throws at you, but also with those patients who are slow to understand the role they must play in their own healing.

MAITRI staff distributing blankets to the poor, MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

Contentment—perhaps it is more of an acceptance, but everyone’s ability to put up with the poorer equipment, the less than comfortable surroundings, the outbursts of barking from the rescued dogs, the overwhelming numbers of patients when it is supposed to be a regular clinic day.

Kindness—it is written through everything. The staff and in-patients mix regularly in formal situations (at check ups, dispensing medicines, ulcer dressing) as well as around the campus. Those hospitalized can spend weeks or months here slowly gaining the strength to return home and thus become part of the MAITRI family. Pre- and post-natal mothers who come for checks can be regular visitors over many years with different births.

MAITRI staff distributing tuberculosis medicine, MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

Generosity—MAITRI not only gives outright (medicines, blankets, supplements for TB patients, sandals for leprosy patients, medical costs for reconstructive surgery, and so on) but also through encouraging reciprocal giving. The Village Schools program was set up to encourage the local community to invest in the education of its children by committing to building and maintaining the school buildings and ensuring boys AND girls attended. Those coming from a long way to receive help are given half their travel costs.

Respect—for those who are the lowest of the low. For those with leprosy, a disease that still attracts social stigma, or mothers with a newborn girl where the father is afraid of another dowry. For a wife with TB whose husband hadn’t given her permission to see a doctor. For a dog paralyzed in an accident who would not be looked after anywhere else.

MAITRI leprosy patients enjoying sweets during the MAITRI new year celebration, MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

Loyalty and total commitment to those individuals that need help and who need it now. Many times I have seen staff work well past lunch, dinner, or knock off time to assist a person or animal needing help. They are also very loyal to their communities and the networks MAITRI has developed over the years. It is these networks that are vital in the TB drug distribution process. They also help in identifying potential cases, people who might otherwise miss out on treatment altogether.

MAITRI’s Director, Adriana Ferranti, had a series of clear goals at the beginning. Most of them have already been achieved, such as the campus buildings and the afforestation of the land. The Aspiration to complete the tasks and do more is always there, even though the money is always tight. “In the Service of others” was and is MAITRI’s modus operandi.

One cannot forget these two guidelines: Perseverance and Courage. No examples are required.

Belen the dog wearing a fresh bandage at MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

Whenever I try to summarise what MAITRI does, it is invariably long-winded and somehow insufficient. How does it manage to help those who really don’t have the karma to be helped? Like that day when a new referral was found to be positive for TB. Imagine being that person who is now embraced by an organization that would move mountains to ensure you get the medical help that you need. So many don’t get noticed, don’t get checked, and don’t get helped through the long process to health. Not many people have the karma to save someone’s life. MAITRI does this week in week out, and has done so for nearly thirty years. Meanwhile Kyabje Thubten Zopa Rinpoche’s voice chants mantras and sutras over the loudspeaker system heard by all.

People carrying donated supplies home from MAITRI Charitable Trust, Bihar, India, January 2018. Photo by Phil Hunt.

Looking at MAITRI like this makes it sound like everything and everyone is working perfectly. This is samsara, and this is Bihar. The individuals being helped are very low in society’s pecking order. There is corruption throughout society, there is neglect and indifference. Services are poor, the climate is harsh, the environment suffers from the weight of humanity. MAITRI itself is hobbled by court cases fighting to recoup losses from some of these social ills. Its buildings need repair, there isn’t enough staff, and those who are here are prone to the usual failings. There is never enough time or money. There are always more sick, ill, or vulnerable. It is an impossible job. Yet here MAITRI still remains, in the service of others with compassion and care.

For more information about MAITRI Charitable Trust, visit their website:

https://maitri-bodhgaya.org/

For more information about the 16 Guidelines for a Happy Life, visit the website:

http://www.16guidelines.org/

17

Buddha statue prior to offering gold-leaf at the Guru bumtsog, Hobart, Tasmania, June 2016. Photo courtesy of Stephanie Brennan.

In June 2017 FPMT in Australia (FPMTA) and Chag Tong Chen Tong Tibetan Buddhist Centre (CTCT) organized 100,000 tsog offerings to Guru Rinpoche, also known as a “Guru bumtsog.” Participants from all over Australia took part in the powerful and joyous multi-day event, which was blessed by a video address from Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Here, Stephanie Brennan, FPMTA National Education/Tour Coordinator, shares a personal account of the Guru bumtsog, which took place during Saka Dawa in Hobart, Tasmania.

FPMT in Australia decided in December 2016 to organize a national 100,000 tsog offerings to Guru Rinpoche puja, inspired by the advice of FPMT spiritual director Lama Zopa Rinpoche. We wanted to connect strongly to Rinpoche and to offer the puja for the long lives of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Rinpoche. We also wished to dedicate the puja for world peace.

This was the first time that this event would be offered in our region. Chag Tong Chen Tong Tibetan Buddhist Centre in Hobart generously co-hosted the event. Tasmania, with its pure air, World Heritage wildernesses, and mountains, and Hobart, with its award-winning restaurants, organic produce, and heritage areas, are very popular tourist destinations.

Hobart hosts an active community of artists and designers who are inspired by Tasmania’s natural environment, and Kickstart Arts, an organization dedicated to community art, partnered with FPMTA and CTCT to serve as the event venue.

A large geodesic white dome was erected in the garden next to where CTCT’s three-meters [ten-feet] high golden Shakyamuni Buddha statue was placed. The golden Buddha formed the focus of the event—a place where we offered silken robes, gold-leaf, and incense. Every evening as darkness fell, we circumambulated while chanting and made the sur offering around a fierce fire. Early each morning, we started by offering tea lights to the large stupa set up in the middle of the dome, the flickering flames lighting our faces in the shadows before the sun rose.

Inside the venue, the gompa was resplendent—luminous with Kickstart’s theatrical lighting, which shone on the rich brocades, thangkas, silk buntings, khatas, and holy images that covered the walls and ceiling, and illuminated tables of beautiful tsog offerings and long lines of water bowl, light, incense, food, and flower offerings.

Offering robes to the Buddha statue during the Guru bumtsog, Hobart, Tasmania, June 2016. Photo courtesy of FPMT Stephanie Brennan.

At the front of the room was a high throne covered in beautiful brocades, holding images of His Holiness and Lama Zopa Rinpoche. There were beautiful crystal bowls overflowing with gold-covered chocolates and mandala offerings on silken cushions. The stage was filled with exquisite tsog—wrapped in brilliant ribbons and coverings—and abundant with Guru Rinpoche incense from Kopan Monastery, crystals, gold-leafed tsatsas, and beautiful objects. Vase upon vase of colorful flowers were lined up in front.

Internationally renowned artist Martin Walker had installed an exhibition of gilded repousse holy images at the venue called Sacred Art for Global Peace. Kickstart Arts’s exhibition room was filled with his wondrous gilded Tibetan Buddhist deities mounted on rich brocades. The image of Prajnaparamita, the Perfection of Transcendent Wisdom, gleamed with fine gold-leaf, as well as green, yellow, white, and red gold-leaf. Her robes were trimmed with purple-leaf (a resin-coated silver-leaf) and also with palladium-leaf; her crown was mounted with Swarovski crystals. A palpable sense of presence emanated from the exhibition room.

We started the puja on Saka Dawa evening, Friday, June 9. More than 160 people, including families with children, crammed into the gompa to listen to special guests—such as the Speaker of the Tasmanian Parliament, the Honorable Elise Archer, and Dr. Sonam Thakchoe, a Tibetan representative and scholar—open the puja. We commenced by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land, the Mouheneenner people, and all Aboriginal elders past, present, and future. The Hon. Elise Archer made the first offering of the puja, presenting a delicate gold and white posy of flowers to the throne.

After chai and cake were served, the first puja session began. With eighteen Sangha present from all over Australia, the gompa was filled with maroon and saffron robes. Sitting in front were two geshes—Geshe Tenzin Zopa, who led the puja, and Geshe Phuntsok Tsultrim, the resident geshe at Chenrezig Institute, Queensland. Also in front was Lama Jimay from Tasmania, who ably assisted with the hook drum.

In the first session, we started by chanting the full verses of the “Prayer to Guru Rinpoche That Spontaneously Fulfills All Wishes” to a poignant and melodic tune. This was followed by the tsog offering prayer and Guru Rinpoche mantra, which were repeated many times. These repetitions were accompanied by cymbals and drums with a very stirring beat. As the pace of these repetitions was fast, it took a little while for everyone to get their head around the Tibetan syllables, but soon everyone settled into a kind of rhythm, with Geshe Tenzin Zopa’s clear voice leading us forward.

Sangha members played the ritual instruments, and the gompa became warm and energized. As I looked at the large thangka of Guru Rinpoche above the tsog offerings, it felt to me that evoking the spirit of Guru Rinpoche and knowing that this puja had been blessed by Lama Zopa Rinpoche beforehand, particularly to clear obstacles, made everything in the gompa seem timeless, vivid, and very clear.

It had taken over six months of preparation to realize the Guru bumtsog. Students, directors, previous directors, spiritual program coordinators, and Sangha from most of Australia’s twenty or so centers, projects, and services attended the event. CTCT had conjured a large team of volunteers to host the many Sangha, prepare the delicious food, look after people, work in the shop, help erect the dome, and install the three-meter golden Buddha statue. We were helped by volunteers from other centers such as Buddha House’s director and spiritual program coordinator, who came early from Adelaide to help wrap the tsog.

There were parking attendant helpers, who braved the cold, 5:30-a.m. air, and an usher team, who were suddenly swamped by more than 160 enthusiastic participants—only eighty people pre-registered, but our panic quickly turned to “Welcome! Here is your goody bag” joy. (And there were gold-leaf tsatsa makers in the months leading up to the event!) Co-organizer Ven. Lindy Mailhot, director of CTCT, and FPMT in Australia wanted everyone to feel welcomed, cared for, and nourished by the puja as well as the food, no matter what obstacles arose. But more than anything, we wished to please the mind of our precious guru.

Geshe Tenzin Zopa led the gompa set-up team in the week before the event, directing with precision, while tirelessly climbing ladders, putting up silk bunting, and hanging holy images, khatas, and thangkas, as well as working with Dan Mailhot (nicknamed the “Golden Buddha Man” for his work in gilding the Buddha) to transport, welcome, and decorate the golden Buddha statue in the garden.

Because the puja was also dedicated to world peace in a time when so much war, terror, famine, and suffering are apparent, this event captured the imagination of those at Kickstart Arts and the Hobart community, as well as participants and sponsors. The Israeli FPMT group who sponsored tsog made their dedication to the overcoming of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. They sent a web link to a moving meeting between Israelis and Palestinians whose families had been killed in the conflict and yet who wished only for peace.

At the food tables and tents in the garden hung with prayer flags, in the gompa, and in the sacred art exhibition, an atmosphere of togetherness and warmth encircled everyone. We started at 6 a.m. on Saturday and Sunday, June 10-11, with light offerings and chanting OM MANI PADME HUM, slowly circumambulating the golden Buddha statue to enter the white dome, the Sangha going first, holding their warm zens around themselves in the cold winter morning.

We also offered gold-leaf to the golden Buddha statue, with the two geshes and Sangha leading us all out to the garden. Artist Martin Walker assisted participants, including many children, with offering gold-leaf to the Buddha’s feet. Sponsors waited in line for two hours for their chance to offer gold-leaf to the huge, beaming, golden Buddha.

As registrar for the event, I received emails from the many sponsors, and in the week leading up to the puja, sponsorships quadrupled. By Saka Dawa, I was seriously overwhelmed, with sponsorships arriving from all over the world—India, Malaysia, Israel, Singapore, Hong Kong, New Zealand. The dedications were beautiful, sometimes heart-wrenching, with a clear abiding love of His Holiness and Lama Zopa Rinpoche. To achieve world peace and inner peace was a constant theme.

Suddenly we received incredible news: Lama Zopa Rinpoche had recorded a video, personally addressing puja participants, and Ven. Holly Ansett was sending it through. Ven. Lindy and I broke down. To hear that Rinpoche had done this for us in Australia, knowing how unbelievably busy he is—words could not describe the feelings of being cared for by him, of the deep connection being made between all of us involved with the puja and the person most precious in our lives, Lama Zopa Rinpoche. It made us weep.

We held five puja sessions per day of Guru Rinpoche prayers. Ven. Lindy and I sat behind our chant leader, Geshe Tenzin Zopa, and were subsumed by the waves of the Guru Rinpoche mantra and tsog prayers reverberating in the gompa and the swift rhythm of the cymbals and drums, which created a trance-like beat. Even with my eyes closed, I could see the details of Guru Rinpoche’s image—present in the gompa through the large thangka and also the exquisite Bertrand Cayla painting on the front of the prayer books we had printed.

Even with a failing voice, Geshe Tenzin Zopa continued to lead us as we entered the world of Guru Rinpoche. Sangha swayed, many with eyes closed; students called out the fast-beating prayers; and the cymbals and drums rattled and shook the gompa. Inside was warmth and light, radiant light. An intense white brightness emanated from the front of the gompa, the silken tsog ribbons and faces of the delicately painted thangka images glittered and shone beneath it. It was hard not to feel a strong presence.

Early morning light offerings during the Guru bumtsog, Hobart, Tasmania, June 2016. Photo courtesy of FPMT Stephanie Brennan.

As we entered our breaks, we came out into a different world, a present and conventionally real world of lunch: warm delicious food and cool wind on our cheeks that made the prayer flags flutter. After lunch, we darkened the gompa to play Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s two videos on a huge screen. The first ten-minute video thanked everyone there for coming to Tasmania to do the Guru bumtsog. Rinpoche, in his characteristic style gave “100,000 thanks” to all of us for coming and for those sponsoring the event and spoke of the incredible good it was doing. He thanked all the geshes. He went into detail of how he remembered Ven. Lindy’s mother making him a head warmer. (That was over thirty-five years ago!)

In the next video, Rinpoche gave a wonderful teaching about Guru Rinpoche and how he arrived in Tibet—his journey there as well as his power in clearing obstacles. It was as if Rinpoche was in the gompa with us, and in fact he was. His spirit and intention was. Rinpoche was with us for the Guru bumtsog, and there was no doubt, listening to these teachings made specifically for us, that what we were doing was of enormous benefit.

Practitioners and volunteers worked beyond their tiredness until the final session. As Geshe Zopa led us in the final prayers and extensive dedications, there was a quiet power that seemed to hum in between the words of the prayers. The gompa was full of faces that were calm and happy, swaying with shining eyes.

FPMT in Australia and CTCT gave out many presents of thanks to the myriad volunteers and hosts who contributed so much. Greatest thanks were reserved for Geshe Tenzin Zopa, who advised and supported Ven. Lindy and myself in all aspects of the event, selflessly giving his time. At the time of thanking him publicly, words choked in my throat; words were not enough.

At the end of the event, students embraced one another, many in tears, as this had been an event where big things had happened internally and also in some other world—of this we somehow felt sure. Guru Rinpoche would help overcome the obstacles at the FPMT centers and in our personal lives—this was Rinpoche’s advice.

This Guru bumtsog was unlike any other puja I had attended. I struggled to find the words to express the power I had connected to. I just kept seeing Guru Rinpoche’s face and robes so clearly in my mind and hearing the sound of his swishing silk and musical instruments. Ven. Lindy and many others reported similar experiences during and after the event.

There was a great love that we had connected to through Lama Zopa Rinpoche and Guru Rinpoche. It manifested in the feelings at the end of the puja in that lit hall where all spontaneously embraced each other and cried. We felt enfolded in the arms of the FPMT family, and we had our hearts opened by our spiritual father, Lama Zopa Rinpoche.

Visit FPMT Australia National Office website for more information on the Guru bumtsog event.

- Tagged: chag-tong chen-tong, fpmta, guru bumtsog, guru rinpoche, in-depth stories, padmasambhava, saka dawa, stephanie brennan

12

Personalizing the Twelve Links of Dependent Origination

Hub portion of Wheel of Life, Khachoe Ghakyil Ling, Kathmandu, Nepal. Photo by Piero Sirianni.

By Ven. Tenzin Gache

His Holiness the Dalai Lama often comments that as Buddhists, our distinctive practice is non-violence, and our distinctive view is dependent origination. His Holiness’s comments echo a common strand in the Buddhist tradition: Lama Tsongkhapa claimed that there was no teaching of the Buddha more profound than dependent origination, and Nagarjuna began most of his works by praising the “one who taught dependent origination.” The Buddha himself recounted that on the night of his enlightenment, he awoke to the profound nature of the twelve links of dependent origination, clearly seeing how beings trap themselves in an endless cycle of self-perpetuating confusion and misery.1 The Buddha went on to claim that nobody could understand his teaching without understanding the nature of these twelve links.2

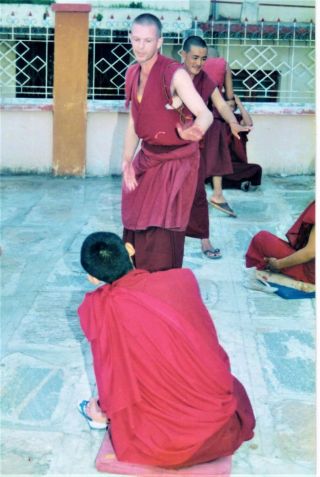

Yet for many Dharma practitioners, these twelve links remain an elusive subject, something difficult to penetrate and even more difficult to relate to one’s personal experience and daily practice. Until several years ago, I was also apt to relegate this topic to the “too hard” pile. But after extensive study and debate with my classmates, and helpful elucidation of difficult points through discussions with Gen Losang Gyatso (“LoGyam”)—a senior monk in my house group, Lhopa Khangtsen,3 at Sera Je Monastic University in South India—I took the subject into retreat for personal contemplation. Although only able to generate some very limited, beginner level insights, I did manage to glimpse how profoundly relevant the twelve links of dependent origination must be for our own psychological situation. I will attempt to share some of my meager understanding in the hope that others will take an interest in studying and contemplating this important but dense subject.

Generally speaking, Buddhist texts that speak of “dependent origination” mean one of three distinct things: 1) dependence upon causes and conditions, 2) dependence on parts, and 3) dependence on a labeling consciousness. The second connotation is central to the philosophy of the Svatantrika-Madhyamaka School, and the third is unique to the Prasangika-Madhyamaka School. Thus, the “distinctively Buddhist” view—the one shared by all Buddhists historically and worldwide—is related to the first connotation, dependence on causes and conditions. This kind of dependence again has two divisions: a) outer cause and effect, and b) inner cause and effect. Outer cause and effect—the arising of smoke from fire, sprouts from seeds—is certainly not a unique Buddhist tenet, so it is inner cause and effect that is so central to Buddhism. Inner cause and effect, or psychological/karmic cause and effect, is the manner in which our present thoughts and actions create our future experience—that is, the twelve links of dependent origination.

This unique Buddhist view avoids the two extremes of 1) believing that some external force, such as a creator god, determines our experiences of happiness and suffering, or 2) believing that human joys and miseries have no deeper meaning, being the mere byproducts of the aggregation and interaction of particles, whose behavior is governed by outer cause and effect. Buddhism breaks away from most modern philosophies in asserting that these outer causes—the matter that interacts with but does not create our minds—are conditions for our experiences of pleasure and pain, but that the root cause lies deeper. All of us wish to have happiness and avoid suffering, and in many cases we have a sincere wish to free others from suffering as well. But as long as we remain ignorant of the true causes of suffering, even the most well-intentioned strokes to eliminate it can have only a limited effect.

What, then, is the cause of suffering? Anyone familiar with the Buddha’s first teaching on the four noble truths will recall that the Buddha insisted that delusions, karmic actions, and craving are the true origin of suffering. But how, exactly, do these three factors create suffering? The clarification of this subtle causal process is the subject of the teaching on the twelve links, a teaching that is simply an expansion of the first two noble truths.

The primary source for Mahayana teachings on the twelve links is the Salistamba, or Rice Seedlings Sutra [translation by author]:

Venerable Bhikshus, whoever sees dependent and relative origination, sees the Dharma.

Whoever sees the Dharma, sees the Buddha.4

What is this dependent and relative origination of which I speak?

It is this: because this exists, that arises. Because this is born, that is born.

It is like this: through the condition of ignorance, compounding factors. From the condition of compounding factors, consciousness … name and form … the six sense spheres … contact … feeling … craving … grasping … existence … birth … aging and death. From the condition of aging and death, agony, wailing, suffering, unhappiness, and mental disturbance all arise. Like that, merely this enormous heap of suffering arises.

The manner in which the twelve links function and interact is not clear in sutras such as the one quoted above, and so different interpretations have arisen over the course of Buddhist history. Some interpret the links as unfolding in a single instant, while others see them as representing stages of life. While I think all of these interpretations are beneficial for contemplation, for the sake of simplicity, I will follow the Gelug interpretation, formulated by Tsongkhapa in texts such as The Golden Garland, Lamrim Chenmo, and Ocean of Reasoning, based primarily upon Asanga’s exposition in Compendium of Manifest Knowledge and to a lesser extent on Vasubandhu’s Explanation of the Sutra on Dependent Relativity. Tsongkhapa’s heart disciple Gyaltsab Je further clarified Asanga’s presentation in his commentary on Compendium. As a Sera Je monk, I will of course rely in part on Jetsun Chökyi Gyaltsen’s textbooks.5

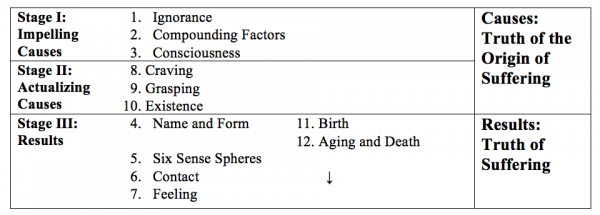

According to Asanga, the progression of the first to the twelfth link, as described in the sutra above, is meant to give a general picture of cause and effect (I will explain how later on), but does not actually illustrate how the process unfolds for a particular action creating a particular result. Instead, a complete cycle of the twelve links unfolds as follows:

Ignorance (1) leads to compounding factors (strong karmic actions) (2), which make an imprint on consciousness (3). Then, craving (8) and grasping (9) ripen that imprint, which then resurfaces in conscious awareness at the time of death as existence (10). The substantial continuum of that mind becomes the first moment of the next rebirth, which is both name and form (4) and birth (11)—these two are simultaneous. From the second moment of that new birth, aging and death (12) begin. During subsequent stages of fetal development, six sense-spheres (5), contact (6), and feeling arise (7), consecutively, and aging and death continue.

Thus, (1), (2), (3), (8), (9), and (10) are the causes, and (4), (5), (6), (7), (11), and (12) are the results. Specifically, (1), (2), and (3) are the impelling causes that leave an imprint on the mind, and (8), (9), and (10) are the actualizing causes that ripen that imprint and lead to a new suffering rebirth. Although this process can appear confusing at first, through habituation we can start to see the logic involved. Also, the non-linear progression highlights that these are twelve links of interdependent origination: although it is possible to trace a particular pattern of cause and effect, all the links should be understood to be mutually reinforcing and interpenetrating. Ignorance causes karmic action, but the imprints of karmic action lead to more ignorance. In a single progression, craving leads eventually to feeling, but feeling itself becomes the main cause for more craving in the future (more on that later). The conceptual structure gives us a microscope to pick out patterns in our own psychology and make sense of what often can seem to be a chaotic, non-linear process.

All twelve of these links are instances of samsara, which is no more than our own body and mind, and the uncontrolled cycles these go through in this life and future lives. Samsara is not a place we cycle through, but the cycle of moving through these twelve links. As the great Indian scholar Kamalashila explained in his Commentary to the Rice Seedling Sutra, “For those confused regarding the process of entering into and reversing samsara, and so that they may be free … the Buddha explained dependent origination.”6 Keeping in mind the general order laid out above, let us now look in more detail at each of the twelve links.

Stage I: Impelling Causes (Links 1, 2, and 3)

1. Ignorance

Generally, any mind that is confused in regards to the object it apprehends is accompanied by the mental factor of “ignorance.” For example, when we see double, the eye consciousness is mixed with ignorance, and when we wrongly believe that somebody’s friendly advice was meant as a criticism, ignorance is involved. Buddhist practice ultimately seeks to free us of all manifestations of ignorance, but with limited time and energy, we need to identify the most important ignorance that is leading us repeatedly to cause suffering to ourselves and others. Even regarding this “first-stage ignorance,” different Buddhist scholars identify it slightly differently: for Asanga, it is like the darkness that leads to misperception, thereby not being a wrong apprehension but rather a lack of apprehension. Dharmakirti insists instead that it is a very specific wrong apprehension, namely the view that there is a substantial, self-sufficient “me” that exists over and above the aggregates of body and mind, similar to there being some kind of substantial entity called “New York” that exists over and above the buildings and people. Chandrakirti adds that it is not only this view of self, but the view of all phenomena possessing some intrinsic, findable nature in this way. The Theravada tradition takes a practical approach, identifying “first-stage ignorance” as misapprehension of the four noble truths: any view of reality that does not recognize craving as the cause of suffering will lead to actions that perpetuate suffering.7 How can we make sense of these various presentations?

Although these authors choose to focus on one particular cause, all of them would agree that all of these causes are involved. We cannot isolate one mistake and toss it out; we have to recognize a vast and deeply entrenched network of misapprehensions that entangles our minds. When a government is riddled with corruption, the result will be ineffective governance and harmful foreign policies. But a campaign to end corruption cannot just fire one person and be done with it. We have to identify and meditate upon all the ways we misrepresent reality: we expect youthful bodies to stay fit and healthy forever, see toxic substances and relationships as sources of stable happiness, and relate to the environment that sustains us as a stockpile for consumption.

2. Compounding Factors (Strong Karmic Action)

Misconceptions naturally lead to poorly planned actions. Every action we do under the power of ignorance is a karmic formation, but some are naturally stronger than others. Those with enough force to impel a new rebirth are called impelling karmas, and that term is synonymous with compounding factors, the second link. Pabongka Rinpoche explains in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand that these are usually actions of body and speech—mere mental intentions rarely have the same level of force, though in certain cases they can.8 A good example of a negative karmic formation is killing somebody under the power of anger. A positive one would be taking a vow to refrain from killing. Until we directly perceive emptiness in meditative absorption, even our most positive actions will to some extent be tainted by wrong conceptions about the self, and thus will lead to rebirth in samsara, albeit a positive one. Each single action is a single impelling karma—two actions do not combine to create one life, though a second action may condition particulars about that life. I asked Gen LoGyam how this provision would work in regard to taking monastic vows—after all, isn’t this something that I perform over time, rather than just a “single action”? He explained that every time a practitioner remembers his or her intention not to harm others or follow attachment, that aspiration is itself a strong imprint that could impel an entire lifetime—so we may create many such imprints each day. Because the intention is to refrain from bodily harm, it becomes an action of body, thus according with Pabongka Rinpoche’s qualification.

The Tibetan word for “impel”—“phen”—can also mean “to throw” or “to shoot” an arrow. Asanga explains that each karma we create is like shooting an arrow straight up into the air. At some point in the future, it will strike down upon the bowman. Remembering that we have countless arrows hovering in the sky in wait for an opportunity to dive is a strong impetus to work out our past karma and limit its further creation.

3. Consciousness

Many years ago when I first read about the twelve links, I was confused as to how consciousness could be the result of karmic formation and ignorance. Is Buddhism claiming that there is no consciousness before that time? Isn’t ignorance itself a kind of consciousness? What I didn’t understand is that “consciousness” here does not refer to consciousness in a general sense, which itself is primordial, existing without beginning, just like matter and space. Rather “consciousness” refers here to a particular instance of consciousness that carries the imprints of karmic actions. Specifically, it is the substantial continuation of the very consciousness that created a karmic action. Gen LoGyam explained, “Imagine if you became furiously angry and killed another person. After completing the action, that anger and aggression would still be manifest in your system. That moment is the third link. After some time—maybe a few minutes or hours, maybe even a day—that energy would calm down, but would not disappear. Instead, it would become dormant in the recesses of your mind as you move on to other thoughts and activities. You may even forget about it, but it would not disappear.”

To understand the concept of “dormant mind,” think of some skill you have developed, perhaps driving a car. Although the knowledge of how to drive a car is strongly imprinted in your mind, you don’t have to consciously think about it twenty-four hours a day. But even if you don’t drive for ten years, when you again sit behind the wheel, that knowledge will become manifest again with little conscious effort. According to Buddhist philosophy, we have many—practically infinite—dormant mental states that reside in a non-manifest manner below our conscious awareness, and wait for a suitable trigger to cycle back up to the surface. Actions done with strong emotion and/or habituation leave strong imprints. These imprints wait for suitable conditions to ripen them and then impinge on our experience.

Stage II: Actualizing Causes (Links 8, 9, and 10)

8. Craving

Although ignorance is the root of cyclic existence, craving is the strong and direct cause that fuels the process. We all want to be happy and avoid suffering, and craving is the natural expression of that dual wish. Twenty-four hours a day—even in dreams—a continuous stream of thoughts and feelings bubbles into our consciousness. These thoughts and feelings fall into link 7, as I will discuss later. The process is normally too subtle for us to recognize, but the thoughts and feelings that arise are imprints of past thoughts and feelings, lying dormant in the mind through the process outlined above in links 2 and 3. Failing to recognize these experiences as being the manifestation of our own mind, we imagine the causes to be present in our immediate circumstances, when in actuality these circumstances are only the trigger for a deeper inner process. At a preconscious level, we constantly engage in habitual thinking that projects qualities onto external objects, labeling them as the cause of happiness or the cause of suffering. We then wish to obtain or hold onto those objects that seem to cause pleasure and separate from or destroy those that seem to cause pain. As such, it is not wanting pleasure and wanting to avoid pain that is in itself the problem, but rather the wrong thoughts that exaggerate the qualities of objects. However, manipulated by ignorance in this way, desire becomes a misguided force, and takes us for ride after ride.

While feeling (7) is like an itch that we can’t even identify, much less scratch, craving is the constant thought that responds to that feeling, thinking, “I’d like to have this, go there, do that.” Not realizing that we are trying to escape a feeling in our own mind, we compulsively engage in new actions, expecting the outer experience to satisfy us. But by the time we get where we intend to go, we have already moved on to thinking about something else, and fail to recognize that the original itch did not disappear but has merely been replaced by another “itch,” the imprint of another past action.

Craving is of three kinds:

1) Craving for pleasure. This is a response to a pleasant sensation, wishing to repeat or prolong that sensation. For example, we may recall eating a particular flavor of ice cream and wish to repeat that experience.

2) Craving for annihilation. This is not a suicidal thought, but rather a thought that responds to a suffering sensation by wishing to avoid it or destroy it. We may recall a bad experience and try to distract ourselves in something enjoyable.

3) Craving for existence. This is a response to the neutral, peaceful sensation of deep meditative concentration, wishing to abide in that sensation perpetually. Gyalwa Gendun Drup, the First Dalai Lama, explains that this is called “craving for existence” in order to dispel the view that the higher realms of meditative absorption are true liberation—they are still within samsaric existence.9

Like scratching an itch, all of these responses only serve to intensify the inner feeling and strengthen the force of past imprints, leading us to engage again in strong karmic actions (2) and thereby thicken ignorance. Tsongkhapa explains in the Lamrim Chenmo that without ignorance, there would be no craving response even if feeling (7) did arise.10 Again we can see how links 1 and 8 mutually reinforce one another.

When feelings arise, the best response would be to carefully observe the nature of the mind and how it responds to those feelings. Habituation to craving makes that simple response extremely difficult, and without realizing, we engage in one action after another, a pattern that will naturally continue at death if we do not retrain the mind.

The First Dalai Lama provides a strong warning about the dangers of craving:

It sweeps us into the torrent of existence, so difficult to cross

And spurred on by violent karmic winds

It churns with the great waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

Save me from the terrifying river of desire!

9. Grasping

The ninth link is merely an intensification of the eighth link, craving, at the time of death. When it becomes apparent that the things that we relied on to support our sense of self—family and friends, wealth and possessions, even our body—will no longer support us, we are left with the feelings with which we have struggled for so long. If our habitual reaction has been to cling to pleasurable feelings and try to avoid uncomfortable ones, that reaction will naturally continue here.

Left with only the inner feeling, this intensified craving response will trigger the ripening of a dormant experience.

10. Existence

The name “existence” here means “samsaric existence” and is a case of the name of the result being given to the cause. This is the last moment of gross consciousness in a lifetime, and becomes the substantial cause for the first moment of consciousness in the next samsaric life. Rather than passing into nirvana, we continue in samsaric existence, so the last experience of our life is called “continued existence” rather than “the end.”

Existence (10) is synonymous with actualizing karma, and is actually the substantial continuity of the impelling karma, link 2, that became link 3 and then passed into dormancy. Remember how Gen LoGyam said this strong mental energy would never disappear? At this point, it reemerges in conscious awareness. Gen went so far to say that if we killed a particular person, the memory of that action, and of that person’s face, will flood our consciousness at the time of death, as though we are reliving the experience. That anger and aggression will then be the powerful imprint that carries us into the next life and conditions our future experiences.

Of course, we may not have created such a heavy imprint in this life, and in that case, an imprint from a karmic action in a past life may also arise. What is certain is that only one imprint will arise—other strong imprints may act as supports, but one particular one will be dominant and become the actualizing karma that directly leads to the next life, like an arrow falling from the sky that has met its mark.

As sense experience fades away, this strong final experience gets “locked in” as our last conscious thought in this life. After that, the mind enters into a subtle, neutral state, and unless a practitioner has actualized the completion stage of highest yoga tantra, he or she will be unable to engage in further practices.

Stage III: Results

4. Name and Form and 11. Birth

Although these two links are listed separately, in the process of a single round of cause and effect, they both occur simultaneously, at the moment of conception in a new life. “Name and form” refer to the mind and body, the aggregates that make up a person. The use of this terminology predates the Buddha, who simply adopted it. Mind is given the label “name” because it engages objects through the force of discriminating “this is this, that is that.”11 “Birth” is not birth from the womb but conception, which for Buddhism is the first moment of a new life. The mind carried into this birth is a continuation of the mind that became dormant at link 3 and manifested again at link 10. Already at conception, our mind, body, and even our environment are charged with the contaminated energy imprinted by our past actions. As Asanga explains in Compendium, “what is the truth of suffering? Know it as the beings who are born, and the world into which they are born.”12

12. Aging and Death

Aging does not simply mean getting gray hair and wrinkles, but refers to the process of constant change that begins at the very moment of conception. Thus, this link begins right away. But because death can occur at any time, even before manifest aging sets in, these two stages are grouped together.

5. Six Sense Spheres and 6. Contact

Name and form (4) lasts until the fetus begins to develop sense organs, at which time link 5 begins. When the sense organs begin to function, and there is the contact of objects, sense organs, and sense consciousness, link 6 begins. We can see the emphasis placed here on the development of conditions that will lead to creating karma once again. We can also see that in this system, a baby in the womb is not a “blank slate,” but is already completing a process that has been set in motion by mistaken views and habitual craving.

7. Feeling

At contact (6), a baby in the womb could already experience feelings of pleasure and pain, but had not yet begun to distinguish certain external objects as the cause of pleasure and pain. When inner thoughts—habituated by karmic imprints from the past existence—reawaken to that process, we enter feeling (7), which lasts until death (unless somebody’s mental faculties deteriorate such that again they cannot distinguish the causes of pleasure and pain). At this point, a person begins to react habitually to feeling with the three kinds of craving—conditioned by ignorance—and again create strong karmic actions. The previous cycle has completed, and a new one begins.

After describing the twelve links individually, the Rice Seedling Sutra continues:

From the condition of aging and death, agony, wailing, suffering, unhappiness, and mental disturbance all arise. Like that, merely this enormous heap of suffering arises.

The teaching of the twelve links does not end with aging and death, but continues on with agony (bodily suffering), wailing (verbal suffering), and three forms of mental suffering. The purpose of this last section is to illustrate the normal progression that life takes, such that we may develop a wish to be free of this uncontrolled process of rebirth. The phrase “merely this enormous heap of suffering” indicates that the process does not involve a substantial self, but is a natural process of cause and effect. The reason this last result is not counted as a thirteenth link is that it does not necessarily follow as a result of aging and death: a pure Dharma practitioner can die peacefully and without regrets.

The question remains: why, if the causal order moves from steps 1-3, then 8-9, then 4-7, did the Buddha originally teach it in the order he did? I believe he did so in order to illustrate the crucial causal nexus of links 7 and 8, feeling and craving. Although in a single set of cause and effect, craving comes first, the feelings we currently experience as the result of countless past cycles are the main cause for the craving that will cause a new cycle. And disentangling this set of cause and effect is decisive in understanding how we create our own suffering. Within the foundational Buddhist practice of the four close placements of mindfulness, the second, mindfulness of feelings, is specifically a means of recognizing the truth of the origin of suffering by closely observing the way feeling fuels the craving that creates future suffering.

Among the five aggregates that constitute a person—form, feeling, discrimination, compounding factors, and consciousness—the first is the body, the last is the main minds, and the fourth includes all mental factors other than feeling and perception. Why, then, are these two singled out? Gen LoGyam explains that it is because they are the two most important in creating samsara. Our attachment to pleasurable feelings, and aversion to unpleasant ones, is the motivating factor in all karmic actions. Discrimination includes our beliefs about the nature of reality, and these determine which actions we believe will maximize pleasure and minimize pain.

Although feeling here includes both sensual and mental sensations, I think that for human beings, subtle mental sensations beyond conscious awareness are often the primary motivating factor in our actions. We are intensely social animals, and relatively few of our actions are directly related to achieving sensual gratification. Much more of our mental energy is focused on how we might like others to perceive us, or spending time with people or in places that we enjoy. As such, what we consider worth pursuing is constructed more by subtle concepts than by biological instinct. So, the feelings most relevant to what we crave are likewise subtle ones. Usually we aren’t even fully aware of our own motivation for actions. A preliminary step towards identifying the relation between this seventh link of feeling, and the eighth of craving, is to slow down and develop sufficient concentration to observe this subtle interplay.

As we first learn to meditate, the uprush of unprocessed feelings can seem like a clogged pipe. But with patience we can learn to identify individual sensations, and may even be able to trace their origin to specific events in our past that have remained unresolved in subliminal levels of the mind. In doing so, we begin to recognize the power of karmic imprints to remain and later influence behavior and experience, and we can apply skillful methods to disarm these dormant—but not inert—imprints, which left unattended can eventually ripen strongly enough to impel entire uncontrolled rebirths. Highly advanced practitioners with superb concentration will eventually move beyond the present lifetime, and trace the progression of cause and effect over multiple lives, much like the Buddha did on the night of his enlightenment. But until we are able to do so, we can contemplate the teaching on the twelve links and begin to gain an intellectual understanding of the process.

Such an understanding itself leaves a strong imprint to eventually gain direct experience and, ultimately, liberation from the process altogether. Even if we cannot gain such profound insight right away, we can learn to be careful of our actions by being watchful of our motivation, paying especially close attention to the way that habitual, unskillful responses to feeling lead to craving and then to unskillful, ultimately self-destructive actions. We can also rejoice in knowing the positive results we can create simply by choosing to abstain from habitual impulses.

What is more amazing than this,

And what is more excellent than this?

By praising you in this way,

It becomes a praise! Otherwise not.

-Tsongkhapa, Praise to the Buddha for His Teaching of Dependent Origination

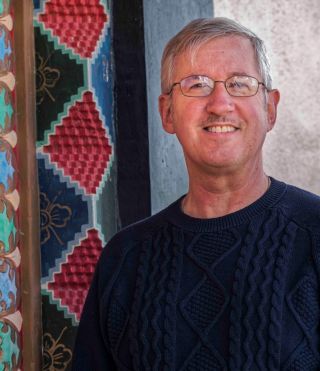

Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter) is an American monk living at Sera International Mahayana Institute (IMI) House in Bylakuppe, India, and studying at Sera Je Monastic University.

1. See Samyutta Nikaya, 12:65; II 104-7.

2. See, for example, Majjhima Nikaya, 28; I 190-191.

3. Like all the monks of Lhopa Khangtsen, Gen LoGyam was a student of Choden Rinpoche. Gen has now completed three of the six years of advanced study to qualify for the degree of Lharampa Geshe. During these three years, Gen achieved the top score in all three monasteries of Sera, Drepung, and Ganden.